Free Range Studios

The Story of Stuff - Referenced and Annotated Script from the Video

Do you have one of these? I got a little obsessed with mine, in fact I got a little obsessed with all my stuff. Have you ever wondered where all the stuff we buy comes from and where it goes when we throw it out.? I couldn't stop wondering about that. So I looked it up. And what the text books said is that our stuff simply moves along these stages: extraction to production to distribution to consumption to disposal. All together, it's called the materials economy.

Do you have one of these? I got a little obsessed with mine, in fact I got a little obsessed with all my stuff. Have you ever wondered where all the stuff we buy comes from and where it goes when we throw it out.? I couldn't stop wondering about that. So I looked it up. And what the text books said is that our stuff simply moves along these stages: extraction to production to distribution to consumption to disposal. All together, it's called the materials economy.

Well, I looked into it a little bit more. In fact, I spent 10 years traveling the world tracking where our stuff comes from and where it goes.[1] And you know what I found out? That is not the whole story. There's a lot missing from this explanation.

For one thing, this system looks like it's fine. No problem. But the truth is it's a system in crisis. And the reason it is in crisis is that it is a linear system and we live on a finite planet and you can not run a linear system on a finite planet indefinitely.[2]

Every step along the way, this system is interacting with the real world. In real life it's not happening on a blank white page. It's interacting with societies, cultures, economies, the environment. And all along the way, it's bumping up against limits. Limits we don't see here because the diagram is incomplete. So let's go back through, let's fill in some of the blanks and see what's missing.

Well, one of the most important things that is missing is people. Yes, people. People live and work all along this system. And some people in this system matter a little more than others; some have a little more say. Who are they?

Well, let's start with the government. Now my friends[3] tell me I should use a tank to symbolize the government and that's true in many countries and increasingly in our own, afterall more than 50% of our federal tax money is now going to the military[4], but I'm using a person to symbolize the government because I hold true to the vision and values that governments should be of the people, by the people, for the people.

It's the government's job is to watch out for us, to take care of us. That's their job.[5]

Then along came the corporation. Now, the reason the corporation looks bigger than the government is that the corporation is bigger than the government. Of the 100 largest economies on earth now, 51 are corporations.[6] As the corporations have grown in size and power, we've seen a little change in the government where they're a little more concerned in making sure everything is working out for those guys than for us.[7]

OK, so let's see what else is missing from this picture.

Extraction

We'll start with extraction which is a fancy word for natural resource exploitation which is a fancy word for trashing the planet. What this looks like is we chop down trees, we blow up mountains to get the metals inside, we use up all the water and we wipe out the animals.

We'll start with extraction which is a fancy word for natural resource exploitation which is a fancy word for trashing the planet. What this looks like is we chop down trees, we blow up mountains to get the metals inside, we use up all the water and we wipe out the animals.

So here we are running up against our first limit. We're running out of resources.[8]

We are using too much stuff. Now I know this can be hard to hear, but it's the truth and we've gotta deal with it. In the past three decades alone, one-third of the planet's natural resources base have been consumed. [9] Gone.

We are cutting and mining and hauling and trashing the place so fast that we're undermining the planet's very ability for people to live here. [10]

[]Where I live, in the United States, we have less than 4% of our original forests left.[11] Forty percent of waterways have become undrinkable.[12] And our problem is not just that we're using too much stuff, but we're using more than our share.

We [The U.S.] has 5% of the world's population but we're consuming 30% of the world's resources[13] and creating 30% of the world's waste.[14]

If everybody consumed at U.S. rates, we would need 3 to 5 planets. [15] And you know what? We've only got one.

So, my country's response to this limitation is simply to go take someone else's! This is the Third World, which - some would say - is another word for our stuff that somehow got on someone else's land.[16] So what does that look like?

The same thing: trashing the place.

- 75% of global fisheries now are fished at or beyond capacity.[17]

- 80% of the planet's original forests are gone.[18]

- In the Amazon alone, we're losing 2000 trees a minute. That is seven football fields a minute.[19]

And what about the people who live here? Well. According to these guys, they don't own these resources even if they've been living there for generations, they don't own the means of production and they're not buying a lot of stuff. And in this system, if you don't own or buy a lot of stuff, you don't have value.[20]

Production

So, next, the materials move to "production" and what happens there is we use energy to mix toxic chemicals in with the natural resources to make toxic contaminated products.

So, next, the materials move to "production" and what happens there is we use energy to mix toxic chemicals in with the natural resources to make toxic contaminated products.

There are over 100,000 synthetic chemicals in commerce today.[21] Only a handful of these have even been tested for human health impacts and NONE of them have been tested for synergistic health impacts, that means when they interact with all the other chemicals we're exposed to every day.[22]

So, we don't know the full impact of these toxics on our health and environment of all these toxic chemicals. But we do know one thing: Toxics in, Toxics Out. As long as we keep putting toxics into our production system, we are going to keep getting toxics in the stuff that we bring into our homes, our workplaces, and schools. And, duh, our bodies. [23]

Like BFRs, brominated flame retardants. They are a chemical that make things more fireproof but they are super toxic.[24] They're a neurotoxin—that means toxic to the brain. What are we even doing using a chemical like this?

Yet we put them in our computers, our appliances, couches, mattresses, even some pillows. In fact, we take our pillows, we douse them in a neurotoxin and then we bring them home and put our heads on them for 8 hours a night to sleep. Now, I don't know, but it seems to me that in this country with so much potential, we could think of a better way to stop our heads from catching on fire at night.

These toxics build up in the food chain and concentrate in our bodies.

Do you know what is the food at the top of the food chain with the highest levels of many toxic contaminants? Human breast milk.[25]

That means that we have reached a point where the smallest members of our societies—our babies—are getting their highest lifetime dose of toxic chemicals from breastfeeding from their mothers.[26] Is that not an incredible violation? Breastfeeding must be the most fundamental human act of nurturing; it should be sacred and safe. Now breastfeeding is still best and mothers should definitely keep breast-feeding,[27] but we should protect it. They [government] should protect it. I thought they were looking out for us.

And of course, the people who bear the biggest brunt of these toxic chemicals are the factory workers[28], many of whom are women of reproductive age.[29] They’re working with reproductive toxics, carcinogens and more. Now, I ask you, what kind of woman of reproductive age would work in a job exposed to reproductive toxics, except one who had no other option?

And that is one of the “beauties” of this system. The erosion of local environments and economies here ensures a constant supply of people with no other option. Globally 200,000 people a day are moving from environments that have sustained them for generations, into cities[30] many to live in slums, looking for work, no matter how toxic that work may be.[31],[32] So, you see, it is not just resources that are

wasted along this system, but people too. Whole communities get wasted.[33]

Yup, toxics in, toxics out. A lot of the toxics leave the factory as products, but even more leave as byproducts, or pollution. And it’s a lot of pollution.[34] In the U.S., industry admits to releasing over 4 billion pounds of toxic chemicals a year[35] and it’s probably way more since that is only what they admit.

So that’s another limit, because, yuck, who wants to look at and smell 4 billion pounds of toxic chemicals a year?

So, what do they do? Move the dirty factories overseas.[36] Pollute someone else’s land!

But surprise, a lot of that air pollution is coming right back at us, carried by wind currents.[37]

Distribution

So, what happens after all these resources are turned into products? Well, it moves here, for distribution. Now distribution means “selling all this toxic contaminated junk as quickly as possible.” The goal here is to keep the prices down, keep the people buying and keep the inventory moving.

So, what happens after all these resources are turned into products? Well, it moves here, for distribution. Now distribution means “selling all this toxic contaminated junk as quickly as possible.” The goal here is to keep the prices down, keep the people buying and keep the inventory moving.

How do they keep the prices down? Well, they don’t pay the store workers very much[[footer]38][/footer] and skimp on health insurance every time they can. It’s all about externalizing the costs.[39] What that means is the real costs of making stuff aren’t captured in the price. In other words, we aren’t really paying for the stuff we buy.

I was thinking about this the other day. I was walking to work and I wanted to listen to the news so I popped into this Radio Shack to buy a radio. I found this cute little green radio for 4 dollars and 99 cents. I was standing there in line to buy this radio and I wondering how $4.99 could possibly capture the costs of making this radio and getting it to my hands. The metal was probably mined in South Africa, the petroleum was probably drilled in Iraq, the plastics were probably produced in China, and maybe the whole thing was assembled by some 15 year old in a maquiladora[40] in Mexico. $4.99 wouldn’t even pay the rent for the shelf space it occupied until I came along, let alone part of the staff guy’s salary that helped me pick it out, or the multiple ocean cruises and truck rides pieces of this radio went on. That’s how I realized, I didn’t pay for the radio.

So, who did pay?

Well. these people paid with the loss of their natural resource base. These people paid with the loss of their clean air, with increasing asthma and cancer rates. Kids in the Congo paid with their future—30% of the kids in parts of the Congo now have had to drop out of school to mine coltan,[41] a metal we need for our disposable electronics. These people even paid, by having to cover their own health insurance.[42] All along this system, people pitched in so I could get this radio for $4.99. And none of these contributions are recorded in any accounts book. That is what I mean by the company owners externalize the true costs of production.

Consumption

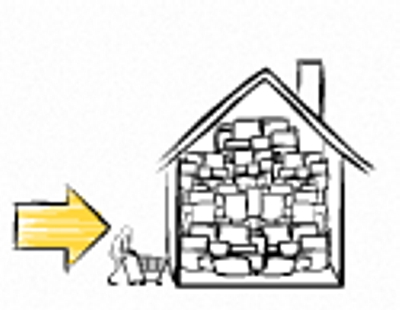

And that brings us to the golden arrow of consumption.

And that brings us to the golden arrow of consumption.

This is the heart of the system, the engine that drives it. It is so important [to propping up this whole flawed system] that protecting this arrow is a top priority for both these guys.

That is why, after 9/11, when our country was in shock, President Bush could have suggested any number of appropriate things: to grieve, to pray, to hope. NO. He said to shop.[43] TO SHOP?!

We have become a nation of consumers. Our primary identity has become that of consumer, not mothers, teachers, farmers, but consumers. The primary way that our value is measured and demonstrated is by how much we contribute to this arrow, how much we consume. And do we!

We shop and shop and shop. Keep the materials flowing.

And flow they do!

Guess what percentage of total material flow through this system is still in product or use 6 months after their sale in North America. Fifty percent? Twenty? NO. One percent.[44] One! In other words, 99 percent of the stuff we harvest, mine, process, transport—99 percent of the stuff we run through this system is trashed within 6 months. Now how can we run a planet with that rate of materials throughput?

It wasn’t always like this. The average U.S. person now consumes twice as much as they did 50 years ago.[45] Ask your grandma. In her day, stewardship and resourcefulness and thrift were valued. So, how did this happen?

Well, it didn’t just happen. It was designed.

Shortly after the World War 2, these guys were figuring out how to ramp up the [U.S.] economy. Retailing analyst Victor Lebow articulated the solution that has become the norm for the whole system. He said: “Our enormously productive economy... demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption... we need things consumed, burned up, replaced and discarded at an ever-accelerating rate.”[46]

And President Eisenhower’s Council of Economic Advisors Chairman said that “The American economy’s ultimate purpose is to produce more consumer goods.”

MORE CONSUMER GOODS??? Our [economy’s] ultimate purpose?

Not provide health care, or education, or safe transportation, or sustainability or justice? Consumer goods?[47]

How did they get us to jump on board this program so enthusiastically?

Well, two of their most effective strategies are planned obsolescence[48] and perceived obsolescence.[49]

Planned obsolescence is another word for “designed for the dump.”[50] It means they actually make stuff that is designed to be useless as quickly as possible so we will chuck it and go buy a new one. It’s obvious with stuff like plastic bags and coffee cups, but now it’s even big stuff: mops, DVDs, cameras, barbeques even[51], everything!

Even computers. Have you noticed that when you buy a computer now, the technology is changing so fast that within a couple years, it’s [your new computer] actually an impediment to communication. I was curious about this so I opened up a big desk top computer to see what was inside.[52] And I found out that the piece that changes each year is just a tiny little piece in the corner. But you can’t just change that one piece, because each new version is a different shape, so you gotta chuck the whole thing and buy a new one.

So, I was reading quotes from industrial design journals from the 1950s when planned obsolescence was really catching on. These designers are so open about it. They actually discuss how fast they can make stuff break and still leaves the consumer with enough faith in the product to go buy anther one.[53] It was so intentional.

But stuff can not break fast enough to keep this arrow afloat, so there’s also “perceived obsolescence.” Now perceived obsolescence convinces us to throw away stuff that is still perfectly useful.

How do they do that? Well, they change the way the stuff looks[54] so if you bought your stuff a couple years ago, everyone can tell that you haven’t contributed to this arrow recently and since the way we demonstrate our value is by contributing to this arrow, it can be embarrassing. [I know.] I’ve have had the same fat white computer monitor on my desk for 5 years. My co-worker just got a new computer. She has a flat shiny sleek flat screen monitor. It matches her computer, it matches her phone, even her pen stand. [It looks cool.] She looks like she is driving in space ship central and I, I look like I have a washing machine on my desk.

Fashion is another prime example of this. Have you ever wondered why women’s shoe heels go from fat one year to skinny the next to fat to skinny? It is not because there is some debate about which heel structure is the most healthy for women’s feet. It’s because wearing fat heels in a skinny heel year shows everyone that you haven’t contributed to that arrow recently so you’re not as valuable as that skinny heeled person next to you or, more likely, in some ad. It’s to keep buying new shoes.

Advertisements, and media in general, plays a big role in this.

Each of us in the U.S. is targeted with more than 3,000 advertisements a day.[55]

We each see more advertisements in one year than a people 50 years ago saw in a lifetime.[56] And if you think about it, what is the point of an ad except to make us unhappy with what we have. So, 3,000 times a day, we’re told that our hair is wrong, our skin is wrong, clothes are wrong, our furniture is wrong, our cars are wrong, we are wrong but that it can all be made right if we just go shopping.[57]

Media also helps by hiding all of this and all of this, so the only part of the materials economy we see is the shopping. The extraction, production and disposal all happens outside our field of vision.

So, in the U.S. we have more stuff than ever before, but polls show that our national happiness is actually declining. Our national happiness peaked sometime in the 1950s,[58] the same time as this consumption mania exploded. Hmmm. Interesting coincidence.

I think I know why. We have more stuff but we have less time for the things that really make us happy: family, friends, leisure time.[59] We’re working harder than ever.[60] Some analysts say that we have less leisure time now than in Feudal Society.[61]

And do you know what the two main activities are that we do with the scant leisure time we have? Watch TV62 and shop.63 In the U.S., we spend 3—4 times as many hours shopping as our counterparts in Europe do.[64]

So we are in this ridiculous situation where we go to work, maybe two jobs even, and we come home and we’re exhausted so we plop down on our new couch and watch TV and the commercials tell us “YOU SUCK” so gotta go to the mall to buy something to feel better, then we gotta go to work more to pay for the stuff we just bought so we come home and we’re more tired so you sit down and watch more T.V. and it tells you to go to the mall again and we’re on this crazy work-watch-spend treadmill and we could just stop.[65]

Disposal

So in the end, what happens to all the stuff we buy anyway? At this rate of consumption, it can’t fit into our houses even though the average U.S. house size has doubled in this country since the 1970s.[66] It all goes out in the garbage. And that brings us to disposal. This is the part of the materials economy we all know the most because we have to haul the junk out to the curb ourselves. Each of us in the United States makes 4 1/2 pounds of garbage a day.[67] That is twice what we each made thirty years ago.[68]

So in the end, what happens to all the stuff we buy anyway? At this rate of consumption, it can’t fit into our houses even though the average U.S. house size has doubled in this country since the 1970s.[66] It all goes out in the garbage. And that brings us to disposal. This is the part of the materials economy we all know the most because we have to haul the junk out to the curb ourselves. Each of us in the United States makes 4 1/2 pounds of garbage a day.[67] That is twice what we each made thirty years ago.[68]

All of this garbage [stuff we bought] either gets dumped in a landfill, which is just a big hole in the ground, or if you’re really unlucky, first it’s burned in an incinerator and then dumped in a landfill. Either way, both pollute the air, land, water and, don’t forget, change the climate.[69]

Incineration is really bad.[70] Remember those toxics back in the production stage? Burning the garbage releases the toxics up into the air. Even worse, it actually makes new super toxics.[71] Like dioxin.[72]

Dioxin is the most toxic man made substance known to science.[73] And incinerators are the number one source of dioxin.[74] That means that we could stop the number one source of the most toxic man-made substance known just by stopping burning the trash. We could stop it today.

Now some companies don’t want to deal with building landfills and incinerators here, so they just export the disposal too.[75]

What about recycling? Does recycling help? Yes, recycling helps. Recycling reduces the garbage at this end and it reduces the pressure to mine and harvest new stuff at this end.[76] Yes, Yes, Yes, we should all recycle.[77] But recycling is not enough. Recycling will never be enough. For a couple reasons.

First, the waste coming out of our houses is just the tip of the iceberg. For every one garbage can of waste you put out on the curb, 70 garbage cans of waste were made upstream just to make the junk in that one garbage can you put out on the curb.[78] So even if we could recycle 100 percent of the waste coming out of our households, it doesn’t get to the core of the problem.

Also much of the garbage can’t be recycled, either because it contains too many toxics or it is actually designed NOT to be recyclable in the first place. Like those juice packs with layers of metal and paper and plastic all smooshed together. You can never separate those for true recycling.[79]

So you see, it is a system in crisis. All along the way, we are bumping up against a lot of limits. From changing climate to declining happiness, it’s just not working.

But the good thing about such an all pervasive problem is that there are so many points of intervention. There are people working here on saving forests and here on clean production.[80] People working on labor rights and fair trade and conscious consuming and blocking landfills and incinerators and, very importantly, on taking back our government so it is really is by the people for the people. All this work is critically important but things are really gonna start moving when we see the connections, when we see the big picture. When people along this system get united, we can reclaim and transform this linear system into something new, a system that doesn’t waste resources or people.

Another Way

Because what we really need to chuck is this old-school throw-away mindset. There’s a new school of thinking on this stuff and it’s based on sustainability and equity: Green Chemistry,[81] Zero Waste,[82] Closed Loop Production,[83] Renewable Energy,[84] Local living Economies.[85] It’s already happening.

Some people say it’s unrealistic, idealistic, that it can’t happen. But I say the ones who are unrealistic are those that want to continue on the old path. That’s dreaming.

Remember that old way didn’t just happen by itself. It’s not like gravity that we just gotta live with. People created it. And we’re people too. So let’s create something new.

- wiserearth.org,

is an international online community directory and networking forum that maps and connects non-governmental organizations working on the critical environmental and social issues of our times.

Recommended Reading

-

Bibliography and Recommended Reading

in chronological order under each heading:

Really, I did. I worked for Greenpeace International, GAIA, Health Care Without Harm, Global Greengrants, and Essential Information from 1988 - 2006. During this time, I was fortunate enough to travel to over 35 countries, mostly visiting factories and dumps. This travel, investigating toxic sites and talking with people in impacted communities, provided me with direct experience and massive empirical evidence on the issues covered in The Story of Stuff.

See also the U.S. Declaration of Independence: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. - That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed."

"Of the world's 100 largest economic entities, 51 are now corporations and 49 are countries." Source: "Top 200: The Rise of Corporate Global Power" by Sarah Anderson and John Cavanagh of the Institute for Policy Studies, Washington, D.C. December 2000. Available at: http://www.ips-dc.org/reports/top200text.htm

Much has been written about the increasing corporate influence over the government in the U.S. and internationally. For a general overview, see: When Corporations Rule the World, by David Korten (1995) and other titles in the Recommended Reading list on storyofstuff.com. Specifically related to industry influence on occupational and environmental health: "Traditional covert influence of industry on occupational and environmental health (OEH) policies has turned brazenly overt in the last several years. More than ever before the OEH community is witnessing the perverse influence and increasing control by industry interests. Government has failed to support independent, public health-oriented practitioners and their organizations, instead joining many corporate endeavors to discourage efforts to protect the health of workers and the community. Scientists and clinicians must unite scientifically, politically, and practically for the betterment of public health and common good. Working together is the only way public health professionals can withstand the power and pressure of industry. Until public health is removed from politics and the influence of corporate money, real progress will be difficult to achieve and past achievements will be lost." in "Industry Influence on Occupational and Environmental Public Health." By James Huff, PhD, in International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, VOL 13/ NO 1, JAN/MAR 2007 • www.ijoeh.com. Also see: "Corporate Junk Science: Corporate Influence at International Science Organizations" by Barry Castleman, R Leman in the Multinational Monitor, January/February 1998, Vol. 19, No 1& 2.

Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins and L. Hunter Lovins, Natural Capitalism, Little Brown and Company, (1999). Excerpted from page 4: "In the past three decades, one-third of the planet's resources, its 'natural wealth,' has been consumed."

Lester Brown, Michael Renner, Christopher Flavin, Vital Signs 1998, Worldwatch Institute, Washington, D.C. "Ninety five to ninety eight percent of forests in the continental United States have been logged at least once since settlement by Europeans." Also, see: "Can't See the Forest," by Josh Sevin, in GRIST, 1 March 2000. "1 to 2 percent of original forests in the U.S. remain undisturbed."

American Rivers, Americas Most Endangered Rivers of 1998 Report, Excerpt: "Today, 40 percent of our nation's rivers are unfishable, unswimmable, or undrinkable" Available at: http://www.americanrivers.org/site/PageServer?pagename=AMR content e2a7

"The U.S. produced approximately 33% of the world's waste with 4.6% of the world's population" (Miller 1998) quoted in Global. Environmental Issues by Frances Harris (2004).

Mathis Wackernagel and William Rees, Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth (1996) and "USA is the country with the largest per capita footprint in the world - a footprint of 9.57 hectares. If everyone on the planet was to live like an average American, we would need 5 planets, or our current planet's biocapacity could only support about 1.2 billion people" from Much Ado About Nothing, October 11, 2006,retreived 11/09/07: http://www.buynothing.biz/blog/index.php?itemid=13

"The third world is that part of the world which became the colonies in the last colonialization. It wasn't an impoverished world then, in fact the reason it was colonialized is because it had the wealth. Columbus set sail to get control of the spice trade from India, it's just that he landed on the wrong continent and named the original inhabitants of this land Indian thinking he had arrived in India. Latin America was colonialized because of the gold it had. None of these countries were impoverished. Today they are called the poorer part of the world because the wealth has been drained out." Vandana Shiva, interviewed in In Motion Magazine, 14 August 1998.

75% of the major marine fish stocks are either depleted, overex-ploited or being fished at their biological limit." Source: World Summit on Sustainable Development 2002, "A Framework for Action on Biodiversity & Ecosystem Management", www.johan-nesburgsummit.org/html/documents/wehab papers.html, cited on The Global Education Project webpage: http://www.theglobaleducationproject.org/earth/food-from-the-oceans.php

See Reality. I realize this sentence sounds harsh. I came to this conclusion after spending over 10 years traveling in Asia, Africa and Latin America, as well as places within the United States, to meet with communities negatively impacted by destructive resource extractive, production, disposal and "development" projects. I saw with my own eyes how, time and time again, whole communities are displaced, ignored, shut out of decision making processes. I spent time with communities in India displaced for industrial complexes, special economic zones, dams, coal fired energy plants and high end tourist facilities. Over and over, I saw community members struggling to be heard in a democratic process, struggling to keep their families, community, health and local economies intact. The consistent characteristic of these impacted, disrespected, ignored communities is that they are poor. They didn't own or buy stuff. Another consistent characteristic in nearly all of them is that they are communities of color. The reality is that poor communities, and communities of color, are disproportionately negatively impacted by the current "development" model.

Many references, including: http://www.ourstolenfuture.org; Worldwatch Institute, State of the World 2006; Nancy Evans (ed.), Breast Cancer Fund, State of the Evidence 2006 Executive Summary, available at http://www.breastcancerfund.org/site/pp.asp?c=kwKXLdPaE&b=1370047; Gay Daly, "Bad Chemistry" (NRDC) at http://www.nrdc.org/onearth/06win/chem1.asp;

"Of the more than 80,000 chemicals in commerce, only a small percentage of them have ever been screened for even one potential health effect, such as cancer, reproductive toxicity, developmental toxicity, or impacts on the immune system. Among the approximately 15,000 tested, few have been studied enough to correctly estimate potential risks from exposure. Even when testing is done, each chemical is tested individually rather than in the combinations that one is exposed to in the real world. In reality, no one is ever exposed to a single chemical, but to a chemical soup, the ingredients of which may interact to cause unpredictable health effects." From Coming Clean Campaign's Body Burden information, retrieved 11/8/07 from http://www.chemicalbodyburden.org

For examples, see: “Body Burden - The Pollution in Newborns: A benchmark investigation of industrial chemicals, pollutants and pesticides in umbilical cord blood” by Environmental Working Group, July 14, 2005; and “Trade Secrets: A Bill Moyers Special Report on PBS” (2001); and Commonweal’s Biomonitoring Resource Center, http://www.commonweal.org/programs/brc/index.html

More information on BFRs, including toxicity information, alternatives and questions about their actual role in sl

- Clean Production Action: http://www.cleanproduction.org/Flame.About.php.

- Environment California: http://www.environmentcalifornia.org/results/environmental-health-results

- Health Care Without Harm: http://noharm.org/us/bfr/issue;

- Kellyn Betts, “Formulating environmentally friendly flame retardants” (http://www.safemilk.org/article.php?id=491);

- and the animated short film on toxic flame retardants, http://www.killersofa.org/article.php?list=type&type=81

BREAST IS STILL BEST. I encourage breastfeeding and want breastfeeding to be safe. I breastfed my daughter and encourage other mothers to do the same. Breastfeeding has enormous health and bonding benefits. AND, breastfeeding should be safe. Mothers should be able to breastfeed without fear. The World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action and International POPs Elimination Project (an international network fighting toxic chemicals) have prepared a joint statement on this topic: www.waba.org.my/RRR/Joint%20Statement%20Mar2004.pdf

More information available at:

MOMS: Making our Milk Safe, http://www.safemilk.org

WABA: World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action: http://www.waba.org

“Along with its antibodies, enzymes, and general goodness, breast milk also contains dozens of compounds that have been linked to negative health effects.” From MOMS (Making our Milk Safe), retrieved 11/11/07 from http://safemilk.org/article.php?list=type&type=52. Full list of chemicals that have been identified in breast milk available on same page. Please note: breast is still best. Keep breastfeeding!!

For example: “Worldwide, according to the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, there are 1.2 million fatalities on the job each year (3,300 deaths per day), and 160 million new cases of work-related diseases. (ICFTU, 2002) Moreover, it is estimated that for each fatality there are 1,200 accidents resulting in three or more days off from work and 5,000 accidents requiring first aid. (Takala, 2002)….’The global race to the bottom’ affects both developing and developed economies as transnational corporations roam the world looking for the lowest wages, the most vulnerable workforces, and the least regulation of environmental and occupational health” excerpted from “The Global Threats to Workers’ Health and Safety on the Job” by Garrett D. Brown, MPH, published in the September 2002 issue of Social Justice, Vol. 29, No. 3, September 2002.; “There are more than 1,000 chemicals used during electronics production and many are known to be hazardous to human health, including lead, mercury and cadmium. Chip manufacturing is especially dangerous with thousands of gallons of toxic solvents used to clean microscopic dust and dirt off the chips. Manufacturing workers and the communities surrounding high-tech facilities are exposed to these toxics and have developed higher rates of cancer, reproductive problems and illness.” From Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition, Electronics Industry Program, extracted 11/10/07 from: http://svtc.etoxics.org/site/PageServer?pagename=svtc_electronic_industry_overview

For example, see: “Reproductive health services for garment factory workers in Bangladesh” by Bayard Roberts, which states: “Over the last decade, the number of garment factories in Bangladesh has increased rapidly in response to foreign demand for cheap labour and materials. The factories employ around 1.5 million workers, most of them young women of reproductive age. Many of these women suffer from chronic ill health.” Available at http://www.kit.nl/exchange/html/2001-4_bangladesh.asp; see also: “Utilization of antenatal services in apparel manufacturing factories in Bangalore” by Joseph B, Charles S, Clement Prakash TJ, Vikas Sudan ML, Jasmine G Department of Community Health, St. John’s Medical College, Bangalore, Karnataka, India in Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Vol. 9, Issue 3, 2005.

“This year, for the first time in human history, more people will live in urban areas than rural areas. Some of the quantitative statistics are staggering. Every day in the world, 200,000 people migrate to cities.” excerpted from Ken Livingstone, “Davos 07: the Sound of the City”. January 27, 2007.

See: From the Fields to the Factories: Central American Free Trade Deal Hits the Region’s Women Workers Harder, by Melissa Hornaday, July 12, 2005; retrieved on 11/9/07 from http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/hornaday071205.html, See also Bill McKibben, Deep Economy, (2007), p.

“For Reporting Year 2005, 23,461 facilities reported to EPA’s TRI Program. These facilities reported 4.34 billion pounds of on-site and off-site disposal or other releases of the almost 650 toxic chemicals. From: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Toxics Release Inventory, http://www.epa.gov/tri/

Multiple articles in the special Export of Hazards issue of the Multinational Monitor September 1984 - Volume 5, Number 9; and Abe Goldman (1980) “The Export of Hazardous Industries to Developing Countries Antipode” 12 (2), 40–47.; and Barry Castleman, ‘The export of hazardous industries to developing countries”, International Journal of Health Services, vol9, no.4, 1979; and “Have Countries with Lax Environmental Regulations a Comparative Advantage in Polluting Industries?” by Miguel Quiroga, Thomas Sterner, and Martin Persson, Resources for the Future April 2007, RFF DP 07-08

“North America has been sprinkled with a dash of Asia! A dust cloud from China crossed the Pacific Ocean recently and rained Asian dust from Alaska to Florida.” Excerpted from The Pacific Dust Express, in “Science @ NASA,” May 17, 2001: http://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2001/ast17may_1.htm; and “U.S. Gets More Asian Air Pollution than Thought” on UC Davis News and Information, July 19, 2005; http://www.news.ucdavis.edu/search/news_detail.lasso?id=7415&title=U.S.%20Gets%20More%20 Asian%20Air%20Pollution%20Than%20Thought; and “Evidence suggests a substantial Asian impact on both North American air quality and regional radiative forcing, based on several factors: the prevailing winds aloft blowing from the west, recent observations of trace gases and dust over North America, and numerical simulations of transport and chemistry.” In Determine the Impacts of Asian Emissions on North America; http://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/aboutus/milestones/asian_emissions.html.

For example: “CEO Compensation 871 times as high as U.S. Wal-Mart Workers, 50,000 times as much as Chinese Workers” from Wal-Mart’s Pay Gap by Sarah Anderson, Institute for Policy Studies, 2005.

Earth Economics (eartheconomics.org) defines an externality as: “Externality: An unintended and uncompensated loss or gain in the welfare of one party resulting from an activity of another party.” Another way to explain this is that there are many real costs of producing things (like using water, dumping waste, contributing to climate change, paying sick worker’s medical care) which are incurred by producing things, but are ignored by the company owners. Since the company owners don’t pay for these real costs, but shift them onto the public and the environment, they are said to “externalize” them which means making someone else pay for them. That is what I mean when I say that the prices of many goods don’t reflect the true cost of making the things. Someone else is paying for the doctors bills, the longer hike to get water after local water is polluted or gone, the impacts of climate change, the cost of the asthma inhaler and more costs incurred from the extraction, production, distribution and disposal of stuff.

See also the following excerpt from David Korten, When Corporations Rule the World, (1995): “If some portion of the cost of producing a product are borne by third parties who in no way participate in or benefit from the transaction, then economists say the costs have been externalized and the price of the product is distorted accordingly. Another way of putting it is that every externalized cost involves privatizing a gain and socializing its associated costs onto the community.

Externalized costs don’t go away - they are simply ignored by those who benefit from making the decisions that result in others incurring them. For example, when a forest products corporation obtains rights to clear-cut Forest Service land at give away prices and leaves behind a devastated habitat, the company reaps the immediate profit and the society bears the long term cost. When logging companies are contracted by the Mitsubishi Corporation to cut the forests of the Penan tribes people of Sarawak the corporation bears no cost for devastating native culture and ways of life.

Similarly, Dow Chemical externalizes production costs when it dumps wastes without adequate treatment, thus passing the resulting costs of air, water and soil pollution onto the community in the form of additional health costs, discomfort, lost working days, a need to buy bottled water, and the cost of cleaning up what has been contaminated. Wal-Mart externalizes costs when it buys from Chinese contractors who pay their workers too little to maintain their basic physical and mental health or fail to maintain adequate worker safety standards and then dismiss without compensation those workers who are injured.

When the seller retains the benefit of the externalized cost, this represents an unearned profit - an important source of market inefficiency. Passing the benefit to the buyer in the form of a lower price creates still another source of inefficiency by encouraging forms of consumption that use finite resources inefficiently. For example, the more the environmental and social costs of producing and driving an automobile are externalized, the more automobiles people buy and the more they drive them. Urban sprawl increases, more of our productive lands are paved over, more pollutants are released, petroleum reserves are depleted more rapidly, and voters favor highway construction over public transportation, sidewalks, and bicycle paths.

Yet rather than demanding that costs be fully internalized, the corporate libertarians are active advocates of eliminating government regulation, pointing to potential cost savings for consumers and ignoring the social and environmental consequences. Similarly they advise localities in need of employment that they must become more internationally competitive in attracting investors by offering them more favorable conditions, i.e., more opportunities to externalize their costs through various subsidies, low cost labor, lax environmental regulations, and tax breaks.”

A maquiladora, also called a maquila, is described by STITCH, Organizers for Labor Justice: “The use of the word ‘maquila’ in Central America originates from the Arabic word maquila, which referred to the amount of flour retained by the miller in compensation for grinding a farmer’s corn in colonial times. Today the term retains some of its original meaning. In current usage, a maquila is a factory contracted by corporations to perform the last stages of a production process --- the final assembly and packaging of products for export. Transnational corporations (TNC’s) supply maquilas with the pre-assembled material, such as cloth and electronic components, and maquilas employ workers to assemble the material into finished or semi-finished products. The maquilas then export 100% of their products back to the TNC’s.” extracted on 11/8/07 from: “http://www.stitchonline.org/archives/maquila.asp More information on maquiladora labor issues is available from the Maquila Solidarity Network (MSN), a labour and women’s rights organization that supports the efforts of workers in global supply chains to win improved wages and working conditions and a better quality of life. http://en.maquilasolidarity.org/

“Coltan is the name for columbo-tantalite mined in Africa. It is a crucial raw material for the production of modern electronics. When refined, the ore becomes tantalum, which is particularly well-suited for use in electric capacitors, because of its ability to hold high electric charges.” (Burge & Hayes, 2002) “Coltan is used in cellular phones, computers, jet engines, missiles, ships, and weapons systems…Without coltan the digital age economy would grind to a halt….. Sixty-four percent of the world’s reserves of coltan are in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), a nation racked by poverty and war.” (Montague, 2002) Many of the Coltan miners are children. See: “Reports say a third of the region’s children are giving up school to dig for coltan.” From Seeing is Believing, Episode 1 Autumn 2002, retrieved 11/11/07 from http://seeingisbelieving.ca/cell/kinshasa/; and “Researchers at globalissues.org estimated that 30 percent of schoolchildren in the northeastern region of the DR Congo have abandoned school to search for Coltan”, from “Dial ‘C’ for Civil War” by Jill Gregorie in GENERATION, retrieved 11/11/07 from: http://www.subboard. com/generation/articles/113927134460289.asp; and “Many coltan miners are children. Some estimates suggest that 30 percent of schoolchildren in the northeastern Congo have abandoned their studies to dig for coltan.” in “A Call to Arms - demand for Coltan causes problems in Congo” by by Kristi Essick, Mark Boslet, Boris Grondahl in The Industry Standard, June 11, 2001; and “The United Nations reports child labour in Africa has significantly increased in coltan and diamond mines. In some regions of the Congo, about 30 percent of schoolchildren are now forced to work in the mines.” Excerpted from: Stats & Facts on Child Labour in Mines and Quarries by Global March Against Child Labor, at http://www.globalmarch.org/events/facts-wdacl.php3; and “Cell phones fuel Congo Conflict” at http://seeingisbelieving.ca/cell/ kinshasa/; also: “Furthermore, reductions in school attendance and the presence of child miners were apparent and oftentimes children served as forced labor “ quoted in “Congo, Coltan, Conflict” by Benjamin Todd in the The Heinz School Review, |Volume 3, Issue 1, March 15, 2006.

For example: “More than 60 percent of Wal-Mart employees - 600,000 people - are forced to get health insurance coverage from the government or through spouses’ plans—or live without any health insurance. Wal-Mart shifts the cost of health insurance to taxpayers and other employers, driving up the health costs for all of us. “and “The average worker would have to pay one fifth of his paycheck for health care coverage at Wal-Mart. On a wage of about $8 an hour and 29-32 hours of work a week, many workers must rely on state programs or family members or simply live without health insurance.” Both excerpted on October 27th from: “The Wal-Martization of Health Care” by United Food and Commercial Workers, retrieved 11/12/07 from: http://www.ufcw.org/take_action/walmart_workers_campaign_info/facts_and_figures/walmartonbenefits.cfm

Much has been written about Bush’s statements encouraging people in the U.S. to engage in business as normal, to go shopping in the aftermath of the 9/11 disaster. See: “Uncle Sam Wants You…to Go Shopping: A Consumer Society Responds to National Crisis,” 1957-2001” by R.H. Zieger, in Canadian Review of American Studies, 2004, vol. 34; part 1, pages 83-104. Examples of news articles include: “Terrorist Attacks Akin To Launching Of Soviet Satellite,” by Kathy Keen, in University of Florida News, retrieved on 11/10/07 from: http://news.ufl.edu/2004/10/28/ sputnik/; and “9/11 trauma persists five years later” by Manav Tanneeru CNN, posted 9/1/2006, retrieved 11/10/07 from http:// www.cnn.com/2006/US/09/08/911.overview/index.html; and “How Much Stuff is Enough” by David Suzuki, July 19, 2002, retrieved on 11/10/07 from http://www.davidsuzuki.org/About_us/Dr_David_ Suzuki/Article_Archives/weekly07190201.asp

Paul Hawken, Natural Capitalism, (1999) p. 81. Note: Since so many viewers have asked about this fact, I’ll include the whole paragraph from Natural Capitalism to provide more explanation: “In short, the whole concept of industry’s dependence on ever faster once-through flow of materials from depletion to pollution is turning from a hallmark of progress into a nagging signal of uncompetitiveness. It’s dismaying enough that compared with their theoretical potential, even the most energy-efficient countries are only a few percent energy-efficient. It’s even worse that only one percent of the total North American materials flow ends up in, and is still being used within, products six months after their sale. That roughly one percent materials efficiency is looking more and more like a vast business opportunity. But this opportunity extends far beyond just recycling bottles and paper, for it involves nothing less than the fundamental redesign of industrial production and the myriad uses for its products. The next business frontier is rethinking everything we consume; what is does, where it comes from, where it goes, and how we can keep on getting its service from a net flow of very nearly nothing at all - but ideas.” (emphasis added by Annie.)

Annie adds: This statement is not saying that 99 percent of the stuff we buy is trashed. Think beyond your household to the upstream waste created in the extraction, production, packaging, transportation and selling of all the stuff you bought. For example, the No Dirty Gold campaign explains that there is nearly 2 million tons of mining waste for every one ton of gold produced; that translates into about 20 tons of mine waste created to make one gold wedding ring.

“Why Consumption Matters” by Betsy Taylor and Dave Tilford, in The Consumer Society Reader Edited by Juliet B Schor and Douglas Holt (2000), p. 467.

David Suzuki, "Economy needs a better goal than ‘more.’" February 24, 2006 available from David Suzuki Foundation at: http://www.davidsuzuki.org/about_us/Dr_David_Suzuki/Article_Archives/weekly02240601.asp

“Progress through Planned Obsolescence” in Vance Packard, The Waste Makers (1960), pp 45 - 57. Also see Made to Break by Giles Slade (2006); and a 20 page pamphlet called “Ending the Depression through Planned Obsolescence” by Bernard London (1932). Brooks Stevens, a U.S. industrial designer is often credited for popularizing the term “planned obsolescence” after he used it in a speech in 1954. Stevens’ defined planned obsolescence as, “Instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary.” (from Industrial Strength Design: How Brooks Stevens Shaped Your World,” Milwaukee Art Museum, June 7 - Sept. 7, 2003.)

Vance Packard calls perceived obsolescence, “planned obsolescence of desirability.” See the chapter by that name in The Waste Makers (1960), p 58-66.

I did this at a workshop called “The Literal and Figurative Story of the Computer” at the Environmental Grantmakers Association’s annual retreat in Mohonk New York in September 2005.

Home Furnishing Daily, Retailing Daily and other journals quoted in Vance Packard, The Waste Makers in the chapter 10,“The Short, Sweet Life of Home Products,” pp 87- 100.

For example, see “Planned obsolescence of desirability” and “How to outmode a $4,000 vehicle in Two Years” and “America’s Toughest Car - and Thirty Models Later” in Packard, The Waste Makers (1960) pp. 67 - 86.

Note that I said we are each targeted with more than 3,000 ads each day, rather than estimating the number we each actually see. I limited the discussion to the number we are targeted with because I believe that the number of ads each person sees daily in the U.S. varies widely and is impossible to know definitively. Some sources cite 3,000 ads per day (e.g. The American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Communications Policy Statement on Children, Adolescents, and Advertising, in PEDIATRICS Vol. 118 No. 6 December 2006, pp. 2563-2569 retrieved on 11/9/07 from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/118/6/2563 and some cite even more (“Yankelovich, a market research firm, estimates that a person living in a city 30 years ago saw up to 2,000 ad messages a day, compared with up to 5,000 today” retrieved 9/27/2007 from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/15/business/media/15everywhere.html). Still others estimate the average per capita daily viewing at far fewer ads. I decided to do my own research on this. For a few days, I carried around a little metal hand held counter and clicked it each time I saw or heard an ad on the radio, computer, billboard or anyplace else. The numbers of ads I viewed daily did not reach 3,000, but I am confident more ads are out there trying to get my attention. Since I don’t watch commercial TV and don’t go to malls, I happily miss a lot of them.

“Each of us sees more ads alone in one year than people of 50 years ago saw in an entire lifetime.” Cited in DMNews magazine, 12/22/97. Another measurement of the increasing volume of ads comes from David Shenk, who estimates that the average American saw 560 daily advertising messages in 1971 and by 1997 that number had increased to over 3,000 per day, in Data Smog: Surviving the Information Glut by David Shenk (1997).

“Advertising must mass-produce customers just as factories massproduce products in a growing economy’ stated the publisher of Printers’ Ink” quoted in Packard, “The Commercialization of American Life” in The Waste Makers, p. 189.

Bill McKibben, Deep Economy (2007), p.35-36 and Vicky Robin, “Towards a Solution to Overconsumption” undated.

Schor (1992); and “ Short on Time? Take Yours Back!” by John de Graaf, in Center for a New American Dream Newsletter, undated, retrieved on 11/11/07 from http://www.newdream.org/newsletter/tbytd.php.

Schor, The Overworked American, chapter 3 “A Life at Hard Labor.” Pp. 43 - 82. “Work and Leisure in Preindustrial Society” by Keith Thomas in Past and Present 29 (December 1964) 61. Cited in Schor, The Overworked American, p. 46.

“American Time Use Survey - 2006” by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) of the U.S. Department of Labor, June 28, 2007, http://www.bls.gov/tus.

Just to clarify, I don’t mean to stop all working and all shopping today. But I want to work for a world in which both the work and the shopping we do nurtures and sustains us, our health, fellow workers, our relationships, our communities, our planet. The way we currently extract, produce, distribute, consume and dispose of stuff, including the oppressive work-watch-spend treadmill, too often undermines all those things. As Conrad Schmidt, an internationally known social activist and founder of the Work Less Party, a Vancouver-based initiative aimed at moving to a 32-hour work week, explained:. “We now seem more determined than ever to work harder and produce more stuff, which creates a bizarre paradox: We are proudly breaking our backs to decrease the carrying capacity of the planet,” (Excerpted from “Why Working Less is Better for the Globe” by Dara Colwell, AlterNet. Posted May 21, 2007)

“Small is Beautiful: U.S. House Size, Resource Use, and the Environment” Journal of Industrial Ecology on Greener Buildings’ Greenbiz. Extracted on 11/11/07 from: http://www.greenerbuildings.com/news_detail.cfm?NewsID=28392

“In 2005, U.S. residents, businesses, and institutions produced more than 245 million tons http://www.epa.gov/epaoswer/non-hw/muncpl/facts-text.htm - chart1 of MSW, which is approximately 4.5 pounds of waste per person per day.” Source: U.S. Environmental

See: Incineration: A Dying Technology by Neil Tangri (2003); Gone Tomorrow by Heather Rogers (2005) and “Landfills Are Dangerous” in Rachel’s Democracy and Health News, September 24, 1998

Tangri (2003); Incineration and Human Health by Pat Costner, Paul Johnston, Michelle Allsopp (2001)

Excerpted from Health Care Without Harm’s webpage, www. noharm.org: Dioxin is the name given to a group of persistent, very toxic chemicals. The most toxic form of dioxin is 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin or TCDD. The toxicity of dioxin-like substances is generally measured against TCDD using “toxic equivalents.” In this system, compounds are assigned a fractional potency relative to TCDD. In most cases, TCDD contributes a small fraction of the total amount of toxic equivalents found in the environment…..Dioxin is a potent cancer-causing agent. The 1994 EPA draft reassessment for dioxin’s effects estimated that the levels of dioxin-like compounds found in the general population may cause a lifetime cancer risk between one in 10,000 to one in 1,000. This is 100 to 1000 times higher than the risk level of one in a million that is deemed acceptable in certain regulations. In 1997, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded that there was sufficient evidence from studies in people to classify dioxin as a known human carcinogen. Dioxin causes reproductive and developmental effects in animals at very low doses. Dioxin exposure damages the immune system, leading to increased susceptibility to infectious disease. It can disrupt the proper function of hormones - chemical messengers that the body uses for growth and regulation. The EPA reassessment found that non-cancer health effects of dioxin may be quite important for public health. According to the EPA, some adverse effects of dioxins may occur at levels just ten times higher than the amounts currently found in the general population. Hence, we are close to “full” when it comes to the amount of dioxin that is expected to cause adverse health effects. The prudent policy is to reduce exposure to dioxin and dioxin-like compounds….Every person has some amount of dioxin in their body. This is because dioxin, like DDT, does not readily break down in the environment. It also accumulates in the body. Continual low-level exposure leads to a “build up” in tissues. According to EPA, over 90 percent of human exposure occurs through diet, primarily foods derived from animals. Dioxin in air settles onto soil, water, and plant surfaces. It accumulates in grazing animals. People then ingest the dioxin contained in meat, dairy products, and eggs. Some exposure also comes from eating dioxin-contaminated fish….Dioxins and furans are not intentionally manufactured except for research purposes. Instead, they are unwanted by-products of many chemical, manufacturing, and combustion processes. Dioxin is formed during industrial processes involving chlorine or when chlorine and organic (carbon-containing) matter are burned together. PCBs were produced in vast amounts until their manufacture was banned in the US. Garbage and medical waste incinerators are the largest sources of dioxin identified by EPA.” (emphasis added). Extracted on 11/11/07 from: http://www.noharm.org/details.cfm?type=document&id=176

“2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD or dioxin), is commonly considered the most toxic man-made substance.” In “Paternal concentrations of dioxin and sex ratio of offspring” in the Lancet 2000; 355: 1858-63, 27 May 2000

U.S. EPA, The Inventory of Sources of Dioxin in the U.S. (1998);Dioxin and Furan Inventories: National and Regional Emissions ofPCDD/PCDF, U.N. Environment Programme (Geneva, Switzerland),May 1999.

See: The International Trade in Wastes: a Greenpeace Inventory, by Jim Vallette and Heather Spalding (1989). See also the film “Exporting Harm” by Basel Action Network, www.ban.org.

Recycling can have enormous benefits for the environment, public health, energy and climate, many of which are listed at http://www.bringrecycling.org/benefits.html. See also: Puzzled About Recycling’s Value? Look Beyond the Bin by US EPA (1998); “Environmental Impacts of Recycling” by the City of Gainesville at http://www.cityofgainesville.org/recycles/busi/env_impact. shtml; “New recycling infrastructure delivering massive environmental benefits”, by WRAP, available at: http://www.wrap.org.uk/wrap_corporate/news/new_recycling_3.html

The Next Efficiency Revolution: Creating a Sustainable Materials Economy by John Young and Aaron Sachs, Worldwatch Institute (1994), p. 13.

I differentiate between true recycling, which achieves a circular closed loop production process (e.g. a bottle into a bottle into a bottle) and downcycling which re-processes a material into a lower grade material and a secondary product (e.g. a plastic jug into carpet backing). True recycling seeks to eliminate the natural resource input and the waste output of making the product. On the other hand, downcycling, at best, reduces the natural recourse input for the secondary item but does not reduce the natural resources needed to make the original item. In fact, by advertising a product as “recyclable” the demand for that first item may actually rise, ironically creating a greater demand for natural resource input. Juicepacks are an example of a notoriously difficult product to recycle since they are heterogeneous and a key to efficient real recycling is source separation of individual materials into homogenous uncontaminated feedstock. Juicepacks are made of multiple materials - often including paper, plastic and metal - fused together so true source separation is impossible. Responding to public demand for recycling, some juicepack manufactures have begun reprocessing used juice packs to reclaim and reuse a portion of the materials. I have heard of juicepaks being pulped and the paper skimmed off for re-use. I have heard of a project to make bricks or roads in less-industrialized countries from juicepacks. I would not call this true recycling since the recovered packs are not made into new packs. This type of “recycling” doesn’t decrease the demand for new resources to make new juicepacks and may in fact stimulate a demand as consumers perceive the juicepack as a green, recyclable product. The best package for real closed loop recycling are durable refillable containers supported by local collection, cleaning and refilling infrastructure, providing local green collar jobs and stimulating the local economy.

"Clean Production is rooted in the Precautionary Principle, which will become even more important as emerging technologies such as nanotechnology bring us new products. Because our supply chains are so global, we are all tied together as producers and consumers. To achieve clean processes and clean products we need full public access to information about emissions from manufacturing plants and product contents. To help us reach sustainable consumption we need closed loop systems for all the products we use in our daily life. If we’re smart global citizens we will learn from nature as we move to a bio-based society.” From Clean Production Action, at http://www.cleanproduction.org/Steps.Introduction.php

Green chemistry protects the environment, not by cleaning up after a polluting process, but by inventing new chemistry and new chemical processes that do not pollute in the first place. Paul Anastas and John Warner in Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice (1998). Warner and Anastas developed the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry which are available at http://www.epa.gov/ greenchemistry/pubs/principles.html. Information on the US EPA’s Green Chemistry Program at http://www.epa.gov/greenchemistry/; Excellent Green Chemistry Fact sheets available from Clean Production Action at: http://www.cleanproduction.org/Green.php

“Zero Waste is a goal that is both pragmatic and visionary, to guide people to emulate sustainable natural cycles, where all discarded materials are resources for others to use. Zero Waste means designing and managing products and processes to reduce the volume and toxicity of waste and materials, conserve and recover all resources, and not burn or bury them. Implementing Zero Waste will eliminate all discharges to land, water or air that may be a threat to planetary, human, animal or plant health.” (Zero Waste Definition prepared by the Zero Waste International Alliance, http://www.zwia.org/standards.html

“Zero Waste is a goal that is both pragmatic and visionary, to guide people to emulate sustainable natural cycles, where all discarded materials are resources for others to use. Zero Waste means designing and managing products and processes to reduce the volume and toxicity of waste and materials, conserve and recover all resources, and not burn or bury them. Implementing Zero Waste will eliminate all discharges to land, water or air that may be a threat to planetary, human, animal or plant health.” (Zero Waste Definition prepared by the Zero Waste International Alliance, http://www.zwia.org/standards.html)

Closed loop production aims to transform the current linear system into a closed loop through tools such as Extended Producer Responsibility, Industrial Ecology and Zero Waste. A systemic approach to Closed Loop Production also seeks to eliminate toxic inputs, protect workers, communities and the environment along entire supply chains, use renewable energy, and eliminate superfluous consumption and more. See http://www.cleanproduction. org/Steps.Closed.php for more details on Closed Loop Production.

“Renewable energy can meet many times the present world energy demand so the potential is enormous.” From United Nations World Energy Assessment: energy and the challenge of sustainability, available at: http://www.undp.org/energy/activities/wea/drafts-frame.html.

See: BALLE, the Business Alliance for Local Living Economies, for examples of businesses already supporting local living economies around the U.S.: www.livingeconomies.org. David Korten describes Local Living Economies as: Living economies are made up of human-scale enterprises locally owned by people who have a direct stake in the many impacts associated with the enterprise. A firm owned by workers, community members, customers, and/or suppliers who directly bear the consequences of its actions is more likely to provide:

- Employees with safe, meaningful, family-wage jobs.

- Customers with useful, safe, high-quality products.

- Suppliers with steady markets and fair dealing.

- Communities with a healthy social and natural environment.

Excerpted from: “Economies for Life” by David Korten in YES! Magazine, Living Economies Issue. Fall 2002.