Jain Cave Temple at Sittanavasal

Stairs to the temple cave

1. The Temple of the Arhats

On the western side of the hill, in the northern side, is the celebrated Jaina rockcut cave temple called Arivar koil (temple of the arhats). It has relics of paintings of 9th century CE. These paintings are second only in importance after Ajanta paintings and have an important place in the Indian art history. It was a flourishing centre of Jaina influence where Jainism flourished for over 1200 years (3rd century BC to 10th century CE).

There is still some uncertainty regarding the origin of this temple. The temple in its architectural style resembles the cave temples built by the Pallava king Mahendravarman (600 - 630 CE). It is claimed that Mahendravarman's territory did not extend beyond Tiruchi, and that Lalitankura pallavesvara griha on the Rock Fort in Tiruchi is the most southern temple he had excavated.

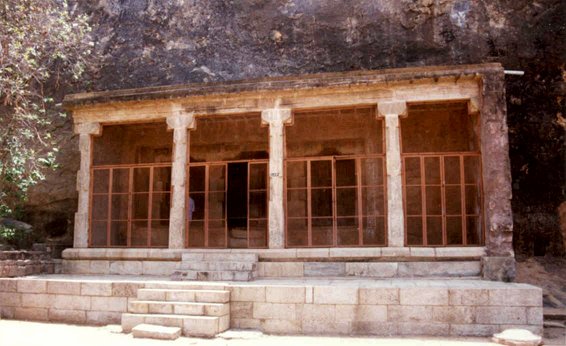

The pillared veranda

It is also known that there are cave temples of this period and of similar style in the Pandya country where the Pallava power was unknown. One such cave temple, dedicated to Siva, with relics of paintings, perhaps belonging to the same period as that of Sittanavasal, is at Tirumalaipuram, near Tirunelveli. In the absence of any foundation inscription it would not be possible to ascertain the builder of this temple. From an inscription dated 9th century, which refers to repair and extension on the temple, one can surmise that this cave temple is anterior to this date.

2. The Discovery of the Temple

This Jaina site and its paintings were first noticed by S. Radhakrishna Iyer, a local historian, and were recorded in his book "General History of the Pudukkottai State" (1916). The impact of Radhakrishna Iyer's reference to the Sittanavasal cave temple and its murals was, however, inhibited by the comparatively regional character of his book and its readership. He himself was not likely to have realized the full importance of Sittanavasal while describing it.

The pillared veranda

The publication in 1920 of Jouveau-Dubreuil's monograph on Sittanavasal was, as a result, accorded the status of a "discovery". While Iyer's notice predates the Dubreuil's, it is the latter that received attention beyond the educated and ruling circles of the erstwhile State. To Dubreuil and the renowned iconographer Gopinatha Rao who collaborated with him in Sittanavasal during the years 1918 to 1920 must be given the credit of placing Sittanavasal before the archaeological world.

In 1942, Dr. S. Paramasivan and K. R. Srinivasan were engaged in cleaning the paintings. They noticed a patch of old painting representing conventional carpet design, over which a new layer of painting was superimposed. This superimposed layer was probably the work of Ilan Gautaman, mentioned in the inscription. The new layer spread into the garbha griham and all over the ceiling of the ardha mandapam, the pillars, the corbels and the beams. This new layer is laid over a ground of plaster over which the paintings that we see today and admire are put up.

Row of seated Tirthankaras with tri chattra

3. The Cave Temple

The cave temple lies on the west face of the hillock. It stands beneath an enormous scarp, which seems likely to fall down upon it. There is an air of somber forlornness about it, altogether appropriate for the severe religion of ultimate mortification of which it has been a centre from ancient times. From the road, a walk of about hundred feet over the sloping rock takes the visitor to the cave temple.

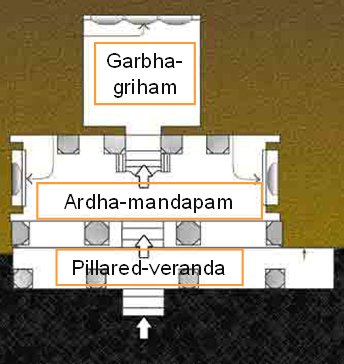

The plan and construction of the temple is simple. It resembles other rock-cut cave temples of 7th century in plan and style. Originally it consisted of only a garbha griham and an ardha mandapam in front, facing west. Both of them are excavated from living rock. According to an inscription dated 9th century, a mukha mandapam was added during the Pandya time. But it must have collapsed, due to neglect. Presently, there is a pillared veranda in front of the cave. This structure is added much latter, in 20th century.

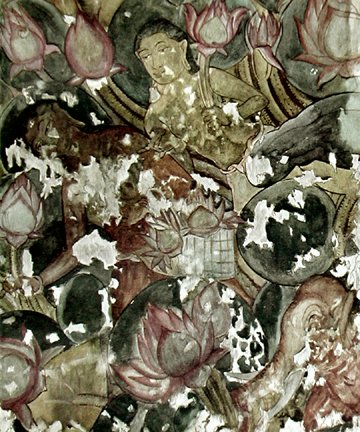

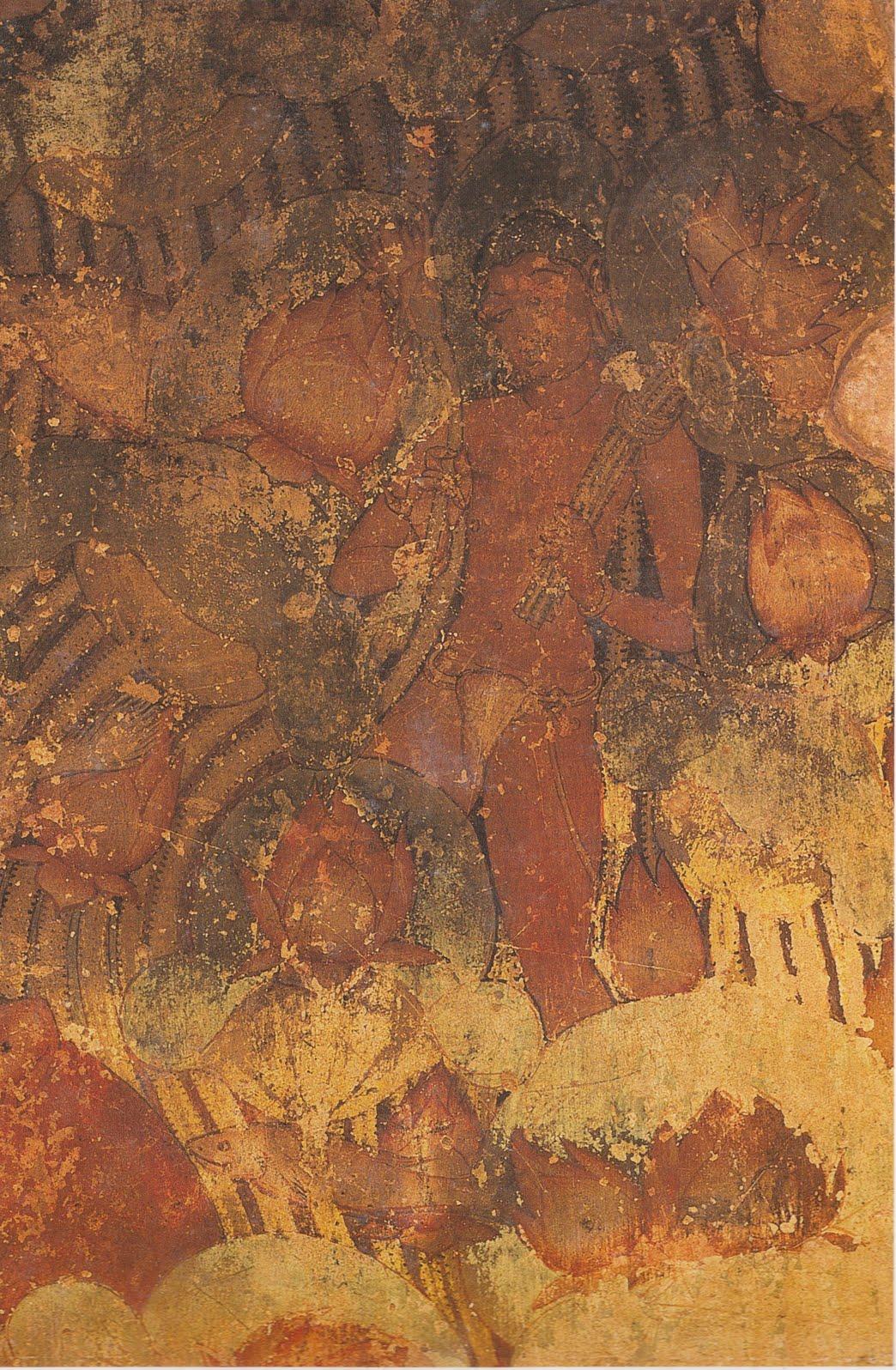

Lotus gatherer (wall painting, Pandya, 9th century CE)

4. The Pillared Veranda

Visitors enter the cave temple through a pillared veranda. This is the latter addition by the Maharaja of Pudukkottai at the instance of Tottenham, the British administrator, in the 20th century. The pillars were brought from the ruins of the Kudumiyamalai temple and the roof-slabs from the quarry of adjoining place called Panangudi. The moulded plinth here is original Pandya. It may be surmised that the mukha mandapam built by the Pandya king must have collapsed. Some point out the debris lying about to prove this.

This veranda is bereft of any detail, except for a famous inscription. This 17-line Tamil inscription on the surface of the rock on the southern flank of this pillared veranda is of great importance giving us some clue to the dating the cave temple. It says that a Jaina acharya named Ilan-Gautaman, also called "the acharya from Madurai", repaired or renovated and embellished the ardha mandapam and added a mukha mandapam in front of the cave temple, which is called in the inscription "Arivar koil" (temple of the Arhat) in Annalvayil village during the reign of the Pandya king Srimaran-srivallabhan (815-862 CE), also called Avanipasekhara.

Lotus gatherer (wall painting, Pandya, 9th century CE)

5. The Ardha Mandapam

Crossing the front veranda one enters the rectangular ardha-mandapam. It measures 22 ½ feet long, 7 ½ feet wide and 8 ½ feet high. It is slightly taller than the garbha-griham. The facade of this ardha-mandapam consists of two massive pillars in the middle and two pilasters, one at either end. The pillars are squarish at the two ends and octagonal in the middle. The pilasters are also of the same design. The rock above the pillars and pilasters is carved in the form of a massive beam. All these pillars and pilasters carry large corbels (potikai) with horizontal roll ornamentation or flutings, with a plain band in the centre.

On either side of the doorway to the garbha griham are ornamented pilasters enclosing two niches, one on either side. These pilasters are smaller but of the same type as the pillars. They have, on the upper cubical parts, lotus medallions carved in bold relief.

On the northern and southern walls of the ardha mandapam are niches. In the northern niche is a figure of a Jaina acharya seated in the dhyana (meditative) pose, cross-legged, with the hands placed one over the other, palms upwards, resting on the folded legs. There is a single umbrella over the head of the image, which proves that it is not that of a Tirthankara. A pillar of the ardha-mantapam. The figure of the Jaina acharya on the northern niche.

Lotus gatherer (wall painting, Pandya, 9th century CE)

On the southern wall, placed in a similar niche, is the figure of Parsvanatha, the twenty-third Tirthankara. He is also seated in the same posture, but with a five-headed serpent spreading its hood over his head instead of an umbrella.

An acharya is a religious teacher and spiritual preceptor. He is the person who administers religious vows for practice by the disciple initiated by him. Tirthankaras are those liberated souls who establish and organize the sangham and whom the Jains worship as Devadi-devas (god of gods). According to the Jaina tradition there are 24 Tirthankaras. The 23rd Tirthankara is called Parsvanatha and he is supposed to have lived in the 8th century BC.

There is an inscription at the bottom (east face) of the pillar near northern figure. It contains the word "thiruvasiriyan", denoting that the figure represented is an "asiriya" that is acharya. It is on the ceiling, the walls, the beams, the cornice and the pillars of this ardha-mandapam that the best known of the Sittanavasal paintings are found. Those on the walls have completely perished and parts of those on the ceilings, the beams and the upper parts of the pillars alone survive.

Lotuses in bloom with duck anf fish (wall painting, Pandya, 9th century CE)

6. The Painting Tradition

The Sittanavasal paintings carry on the tradition of the well known Ajanta frescoes (2nd century BC-6th century CE), Srilanka's Sigiriya (Srigiri) frescoes of the fifth century CE and the Bagh frescoes in Madhya Pradesh of the sixth and seventh centuries CE. Sittanavasal is, therefore, an early example of the post- Ajanta period, and in merit it compares well with Ajanta and Sigiriya. We may safely say that Sittanavasal is one among the earliest frescoes so far known in South India, and that they are the only example of early Jaina frescoes.

The technique employed is what is known as fresco-secco, that is, the painting is done on a dry wall. (In the Europe mural paintings are done on a moist wall and are called fresco-bueno). In this process the surface to be painted is first covered with lime plaster, then coated with lime-wash and the painting done on it.

According to Dr. S. Paramasivan, who had made thorough analysis of the techniques of Sittanavasal paintings, the following pigments have been employed: lime for white, lamp black for black, ochres for yellow and red, terre verte for green, etc. Thus mineral colours, which are of a permanent nature, have been employed. But the information-board put up by the ASI states that vegetable dyes have been employed for the paintings.

In 1937-39, Maharaja of Pudukkottai had the paintings cleaned. After cleaning the paintings, they applied a preservative coating, and strengthened the painted plaster wherever it was loose, by injecting suitable cementing material without retouching any part of the paintings.

Prince and princess (wall painting, Pandya, 9th century CE)

7. The Sittanavasal paintings

This Jaina cave temple is world famous primarily for its mural paintings. The ceiling of the sanctum and ardha-mandapam of this cave temple contain beautiful paintings. These paintings are of the classical or Ajanta style with variations in the handling of the materials by the artists. They furnish a connected link between the Ajanta paintings (4th - 6th century CE) and the Chozha paintings of 11th century at Thanjavur. The sculpture and the matchless paintings of the cave are worth studying in detail.

Originally the entire cave temple, including the sculptures was covered with plaster and painted. The paintings are now found on the ceiling, top part of the pillars and the beam above the pillars. All these paintings, which would rank among the great paintings of India, are barely visible now, mainly due to vandalism during in the last 50-60 years.

These paintings include, as its subject matter, the Jaina Samavasarana, and in it the khatika-bhumi including a lotus tank, flowers, animals, bhavyas and dancing Apsaras, a royal couple and hamsas.

Duck with floriated tail (wall painting, Pandya, 9th century CE)

8. The Samavasarana in Jaina tradition

Jainism is one of the oldest living religions of the world. The ultimate goal of every Jain is the attainment of nirvana or liberation of soul from the bondage of karmas.

Even though there is no emphasis on worship of Gods in Jainism, it teaches the worship of all liberated souls, which have advanced in their spiritual journey irrespective of the level of their achievement. So the worship of the great souls or heroes occupies an important place in the life of Jains.

According to the Jaina tradition there are 63 Salaka-purushas (Great-Souls). It includes 24 Tirthankaras, 12 emperors (Chakravarti) and 27 other heroes. Of these the Tirthankaras occupy the most prominent place and are venerated as Devadi-devas (God of Gods). They are in a sense the religious prophets of the Jains.

A soul attains the position of a Tirthankara after doing good actions. Every Tirthankara, before getting his enlightenment had to go through numerous births in different forms.

Depiction of a lotus gatherer (wall painting, Pandya, 9th century CE)

Five important events in the life of a Tirthankara are important, and are depicted in the temples and narrated in puranam works. They are the birth, the renunciation, the realization (attaining kevala-gnana), the first sermon and nirvana (liberation of soul). The Tirthankara after obtaining kevala-gnana delivers a sermon in a specially designed audience hall called Samavasarana. Gods and goddesses, human beings, birds and beasts come to witness the grand scene of the Lord's discourse. The parallel in Saivism to this hall is called as devasiriya-mandapam as can be seen in the Thiruvarur temple.

Samavasarana, the most attractive heavenly pavilion, is a favorite motif for representation in the Jaina temples. Bhavyas are those fortunate people who become entitled to attend the divine discourse in the Samavasarana structure. They have to pass through -17- seven bhumis or regions before they occupy their seat to hear the divine discourse. Among these, the second bhumi is called the khatika-bhumi (region of the tank). It is a delightful tank with fishes, birds, animals and men frolicking in it or playing in it. The bhavyas are said to get down into the tank, wash their feet and please themselves by gathering lotus flowers, while animals such as elephants, buffaloes and birds and fishes are frolicking about and pleasing themselves too as best as they can. This tank is the one painted on the ceilings of the cave temple.

Female dancer with hand thrown up in glee (wall painting, Pandya, 9th century CE)

9. The paintings on the ceiling

Canopies of different floral patterns are painted on the ceiling over the two images in the ardha-mandapam. That over Parsvanatha has both natural and conventional lotus flowers, the former in full blossom against a lotus-leaf background. That over the acharya has only a conventional lotus-pattern.

In the centre up to the borders of the carpet canopy is painted an exquisite composition, 'The Samavasarana', a lotus tank with the Bhvyas collecting flowers and animals and fish frolicking.

Female dancer with the head and hands preserved (wall painting, Pandya, 9th century CE)

10. The Samavasarana composition

The scenes of this composition are from the Samavasarana, one of the delightful heavens of the Jains, explained before. The painting shows bhavyas diverting themselves in a pool, full of flowering lotuses, called khatika-bhumi. The flowers with their stalks and leaves, and the birds, fishes, makaras, bulls and elephants are shown with a perfect simplicity, charm and naturalness.

The pose and expression of the bhavyas shown in the picture have a charm and beauty, which compel attention. Two of them are shown together in one part of the tank. One is picking lotus flowers with his right hand and has a basket of flowers slung on the other. He is represented in a deep red colour. His companion carries a lotus in one hand, the other is bent gracefully, the fingers forming the mrigi-mudra (deer-gesture). His colour is orange, showing the merit of the soul. The third bhavya, an extremely beautiful figure, also orange in colour, is apart from the others. He carries a bunch of lotus over his left shoulder and lily over his right. The three figures are naked except for their loincloths. The hair is neatly arranged and the lobes of the ears are pendant.

Ground plan of the temple caves

Subramanian Swaminathan

Subramanian Swaminathan