Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

From the late sixteenth to the early seventeenth centuries, Śvetāmbara Jains from Gujarat frequented the Mughal court in substantial numbers. They participated in a variety of cross-cultural exchanges with royal figures and composed Sanskrit texts that explore the implications of their imperial connections. I detail both the social and textual aspects of Jain-Mughal interactions in my dissertation, titled Cosmopolitan Encounters: Sanskrit and Persian at the Mughal Court, which I will defend in March 2012 at Columbia University.[1] My work examines the impact of political relations with the Mughals on Gujarati Jain communities and draws critical attention to an understudied and important series of Jain-authored Sanskrit works.

In my thesis overall, I analyze a broader set of interactions between members of Sanskrit and Persian literary cultures at the Mughal court during the years 1570-1650 CE. During this period, the Mughals rose to prominence as one of the most powerful empires of the early modern world. Through lavish patronage they fashioned their central court as a cultural mecca that attracted Persianspeaking intellectuals from across Asia. Simultaneously, imperial leaders supported Sanskrit textual production, sought out prominent Jain and Brahmanical figures, and underwrote Persian translations of Sanskrit literature. For their part, Indian intellectuals from diverse backgrounds became influential members of the Mughal court and composed Sanskrit works that engaged with diverse aspects of the imperial polity. My dissertation provides the first detailed account of these multifaceted exchanges. Furthermore, I contend that these cross-cultural events were central to the construction of power in the Mughal Empire and to the dynamics of Sanskrit literary culture that involved both Jains and Brahmans in early modern India

My initial concern in the dissertation is to reconstruct the patronage ties that both Jain and Brahmanical communities forged with the royal courts of Akbar (r. 15561605) and Jahangir (r. 1605-1627). These two groups followed different trajectories at court and so provide a useful comparative study. Both communities first entered the imperial milieu in the 1560s, although the Jain presence became pronounced only after the Mughal takeover of Gujarat in 1572-73. Brahmans hailed from a wide range of regional areas and advanced a diverse array of interests in their encounters with the Mughals, often working on behalf on local rulers. In contrast, Jains tended to pursue a relatively consistent agenda of soliciting political concessions beneficial to Gujarat and Jain religious interests.

Jain visitors to the Mughal court generally belonged to one of two communities, the Tapā Gaccha or the Kharatara Gaccha, which often competed with one another for royal favor. One particularly contentious issue was control of Śatruñjaya, a popular pilgrimage location in Saurashtra, and both sects secured royal decrees ensuring their administration of the site on different occasions. Nonetheless, the Tapā Gaccha was generally more active at court, and arguably the most famous Jain to grace the Mughal court was Hīravijaya Sūri, the leader of the Tapā Gaccha 1544-1596. He convinced Emperor Akbar to issue several imperial orders in 1582 that ensured the release of Gujaratis imprisoned by the Mughals, prohibited animal slaughter during the festival of paryuṣaṇa, and cancelled certain pilgrimage taxes. After Hīravijaya, a wave of Jain ascetic and lay leaders visited the Mughals over the next thirty years, and select individuals, such as Siddhicandra, spent extended time in imperial circles and learned Persian.

Śatruñjaya, Palitana, Gujarat. Photo: Audrey Truschke, 2010

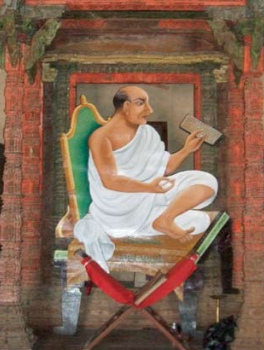

(Above) Image of Hemacandra at Hemacandra Jñāna Mandir, Patan, Gujarat. (Right) Assorted Manuscripts in New Delhi and (below) boxes for manuscript storage at Hemacandra Jñāna Mandir, Patan, Gujarat. Photos: Audrey Truschke, 2010

Jain-Mughal relations disintegrated relatively rapidly in the early seventeenth century. In the 1610s, Siddhicandra, a still young Tapā Gaccha monk, disobeyed Jahangir's direct command to take a wife. As a result, Jahangir banished nearly all Jains from his presence and also forbade Jain ascetics from entering populated centers across the entire Mughal Empire. This expulsion affected both the Kharatara and Tapā Gacchas, and each tradition reports that they played a crucial role in persuading Jahangir to rescind his severe proclamation so that Jains might again move freely about the Mughal kingdom. Even after the order of eviction was canceled, however, Jains never regained a prominent place in the emperor's esteem.

In addition to pursuing imperial connections, Jains also wrote extensively in Sanskrit about their experiences at the courts of Akbar and Jahangir. Interestingly, these Jain-authored works are framed by a near total absence of comparable records on the part of Brahmanical communities. Brahmans far outnumbered Jains as recipients of Mughal patronage but overwhelmingly decided that they could not allow such interactions to permeate the Sanskrit literary world. Here Brahmans were perhaps influenced by the longstanding disinclination of Sanskrit literati to write about Islam or Islamicate culture. Jain texts on relations with the Mughals testify to a plethora of other possibilities that were seen and explored by some Sanskrit participants in such exchanges.

I devote a full chapter of my thesis to five accounts of Jain-Mughal relations composed in the late sixteenth to the mid-seventeenth centuries.[2] Each work is devoted to the life of one prominent ascetic or lay leader and falls into the genre of either mahākāvya (great poem) or prabandha (narrative literature). The authors typically embed events connected with the Mughals into a larger narrative that eulogizes a select individual. These works, all directed to sectarian Jain audiences, provide great insight into how members of the Tapā and Kharatara Gacchas conceptualized the meanings and implications of their imperial ties.

The earliest work, Padmasāgara's Jagadgurukāvya (Poem on the Teacher of the World), was penned in 1589 and offers the first Sanskrit history of the Mughal Empire. The work overall eulogizes the life of Hīravijaya, but Padmasāgara devotes one-third of his text to detailing the military exploits of Humayun and Akbar. Moreover, he departs significantly from known Indo-Persian historiography and constructs a startlingly innovative storyline for the early days of the Mughal Empire that elides the fifteen year Sur Interregnum (1540-1555) when the Mughals lost control of their kingdom. I argue that Padmasāgara crafted this imagined past as an essential framework for understanding the life of Hīravijaya, whom he envisioned as operating within a Mughaldefined world.

After Jagadgurukāvya, Sanskrit texts focused on varied aspects of Jain-Mughal relations. All the works written by Tapā Gaccha authors narrate the initial meeting of Akbar and Hīravijaya Sūri in 1582. Among the retellings of this encounter, Devavimala offers a particularly noteworthy version in his Hīrasaubhāgya (Good Fortune of Hīravijaya, c. early seventeenth century). He relates a conversation that took place during this visit between the Tapā Gaccha leader and Abū al-Fazl, Akbar's vizier, in which the latter provides an exposition of basic Islamic beliefs that touches upon God, the afterlife, heaven, and hell. In writing about this exchange, Devavimala allows for an unprecedented admission of Islam into the Sanskrit thought world, albeit only to be contradicted by Jain views as articulated by Hīravijaya.[3]

Several writers discuss the assorted cross-cultural activities that Jains propagated in the royal milieu. For example, a Tapā Gaccha monk named Bhānucandra taught Akbar to recite Sūryasahasranāma (Thousand Names of the Sun) in Sanskrit.[4] Persian court chronicles also attest to this imperial practice.[5] Both Tapā and Kharatara sources describe a Jain religious rite that members of both communities performed on the Mughals' behalf when Jahangir's daughter was born under threatening astrological circumstances.[6] Jains also participated in Mughal Persianate culture, and Siddhicandra attests to having read Persian books with the royal princes.

Last, Jains address the dangers they faced in entering a milieu where Mughal authority reigned supreme. In this vein, Tapā Gaccha intellectuals report multiple occasions when Hīravijaya and later his successor, Vijayasena, were called upon to prove the theistic nature of Jain beliefs before Akbar. There was an understanding within the Mughal court that different religious convictions were tolerable but atheism was beyond the pale of acceptability, and so Jains risked losing their power ful courtly connections if they lost these debates. In the written records of these discussions, Jain leaders offer divergent answers regarding who constitutes "God" in their system of belief (usually either Jina or karma) but always end victorious. Tapā Gaccha authors were also attuned to the perils that court life presented to monks in terms of maintaining their spiritual obligations. In the penultimate episode of his Bhānucandragaṇicarita (Acts of Bhānucandra), Siddhicandra articulates some of the most deeply rooted objections to Jain relations with the Mughal court in the seemingly true (although heavily embellished) story about his steadfastness in asceticism against the wishes of Jahangir and his wife, Nur Jahan.[7]

The research library at Shri Mahavir Jain Aradhana Kendra, Koba, Gujarat. The library is called 'Acharya Shri Kailasasagarsuri Gyanmandir'. Photo: Audrey Truschke, 2010

These Jain accounts of the Mughals are a rich archive that has much to contribute to our Persian-centered narrative of the Mughal Empire, as well as our understanding of Sanskrit literary culture in the early modern period and of Jain religious and political identities. I strive to draw out the divergent implications of these texts and contend that Gujarati Jains found it advantageous not only to pursue relations with the Mughals but also to incorporate narratives about their courtly encounters within their own written tradition.

Audrey Truschke is a PhD candidate at Columbia University, in the Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies department. Her research interests include Sanskrit, Persian, Mughal history, translation studies, and cross-cultural interactions.

Part of my dissertation work on Jains in Mughal India is also forthcoming as an article: Audrey Truschke, "Reimaginations of the Mughals in Jain Sanskrit Literature," in Kyoto Papers in Jaina Studies, eds. Nalini Balbir, Peter Flügel and Shin Fujinaga (Kyoto, forthcoming).

Padmasāgara's Jagadgurukāvya (1589), Jayasoma's Mantrikarmacandravaṃśāvalīprabandha (1594), Devavimala's Hīrasaubhāgya (c. early 17th century), Siddhicandra's Bhānucandragaṇicarita (c. early 17th century), and Hemavijaya's Vijayapraśastimahākāvya (c. early-mid 17th century; commentary added by his disciple, Guṇavinaya, in 1632).

On this section of Hīrasaubhāgya, also see Paul Dundas, "Jain Perceptions of Islam in the Early Modern Period," Indo-Iranian Journal 42, no. 1 (1999): 35-46.

Siddhicandra, Bhānucandragaṇicarita, ed. Mohanlal Desai (Ahmedabad-Calcutta: Sanchalaka-Singhi Jaina Granthamala, 1941), 2.67-72 and 2.106-109

Abū al-Fazl ibn Mubārak, Ā'īn-i Akbarī, ed. Sir Sayyid Ahmad. (Aligarh: Sir Sayyid Academy Aligarh Muslim University, 2005 reprint), 367; 'Abd al-Qādir Badā'ūnī, Muntakhab al-Tavārīkh, ed. Captain W. N. Lees and Munshi Ahmad Ali. (Calcutta: College Press, 1865), 2:260-261 and 2:322.

Bhānucandragaṇicarita, 2:140-168. Jayasoma, Mantrikarmacandravaṃśāvalīprabandha, ed. Acharya Jinavijaya Muni. (Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1980), vv. 359-365.

Bhānucandragaṇicarita, 4:237-337. Based on Kharatara inscriptions and texts about interceding in the aftermath of this event, the argument and exile seem to have actually occurred. Mohammad Akram Lari Azad, Religion and Politics in India During the Seventeenth Century (Delhi: Criterion Publications, 1990), 119.

Audrey Truschke

Audrey Truschke