According to the doctrine of karma, the space occupied by a soul, is also simultaneously filled with karmic matter and there is incessant interaction between the two substances. The conditions of the soul which cause the influx of matter into the soul is called āśrava (which is dealt with in chapter 5). The influx is not stopped even for a single instant of time, till the soul is totally motionless, that is freed from all activities.

Thus, the soul under the influence of passions, produced by the beginningless perversity and possessed of yoga—threefold activities—mental, vocal, and physical-attracts[1] the karmic matter which is converted into karma with various potencies of distorting and defiling the soul.

The karmic matter—karma—obscures and/or obstructs the characteristic attributes of the pure and perfect soul and keeps it away from its supreme state of existence.

Classification of karma: Karma is classified into eight main types and 148 sub-types, each as them with a precise function to obscure, cripple, or distort fundamental and other attributes of the soul. They are, further, classified into various groups from different aspects.

Of the eight main types, the four are called ghātῑ, because they obscure four fundamental qualities of the soul. That is, they obscure (i) knowledge (jñāna), (ii) intuition (darśana), (iii) perverts and deludes the soul and (iv) obstructs the infinite energy. The remaining four are called aghātῑ, as they do not obscure or obstruct any fundamental attribute of the soul, but (i) produces feelings of pleasure and pain, (ii) builds the body (iii) determines the status and (iv) determines the life-span. From another aspect they are classified into (i) auspicious and (ii) inauspicious.

Each of the four ghātῑ karma and their sub-types mentioned above, are always inauspicious or sinful (aśubha or pāpa). However, the sub-types of the four aghātῑ karma are divided into auspicious and inauspicious. Those sub-types whose fruition results in enjoyment of pleasure are auspicious, while those whose fruition results in suffering and miseries are inauspicious. Now the nature of fruition of a karma is determined by the nature of the activities of the soul at the time of its bondage. If the activity is virtuous (śubha), the bondage of karma will be some of the auspicious sub-types and their fruition will lead to enjoyment. On the other hand if the soul is engaged in sinful (aśubha) activities, the bondage will be inauspicious and their fruition will lead to not only crippling of some fundamental attributes of the soul but also to miseries and pain in the worldly life.

Obviously the bondage of the inauspicious karma (pāpa) is always to be deprecated since it serves no good purpose at all. But the bondage and fruition of auspicious karma—puṇya or merit—is desirable in the worldly state of existence and not universally deprecated. All that is enjoyable and pleasant in the worldly life can be obtained only by the fruition of puṇya. Long life, health, wealth and happiness and, whatever else that makes worldly life enjoyable result from the fruition of one or another of the four auspicious karma.

The bondage of merit—puṇya is exclusively due to good or virtuous activities. Now an activity can be qualified to be called virtuous only if it is within the ambit of Dharma, and dharma is also the means of attaining emancipation. But enjoyment of wealth etc. in the worldly life, is again, deprecated as an hindrance to self-realization. Here, then, is a complicated situation—a paradox. How can dharma, ultimately, become a hindrance to emancipation? If the result of merit—puṇya is an obstacle in the path of emancipation, the question is—should one be engaged in virtuous activities or not?

In this chapter, the author has unequivocally divulged the real and ultimate nature of the so called auspicious karma. The function of penance and such other activities is primarily the production of purity of the soul by the expulsion of the karma. Merit (puṇya) is an incidental by-product that accompanies the spiritual purification much in the same way as chaff is an incidental growth accompanying the corn which, alone, is the essential product of cultivation. And, therefore, it is not proper to contend the necessary concomitance of merit with penance.

In the end the position is made clear by a simple analogy. Bondage of the soul by karma is compared to fetters. And the bondage of inauspicious karma can be regarded as fetters made of iron, while that of auspicious karma is to be taken as fetters made of gold. But both are equally efficient to keep the soul bound to the cycles of births. They are on the same footing with reference to summom bonum which is final liberation and freedom from all bondage.

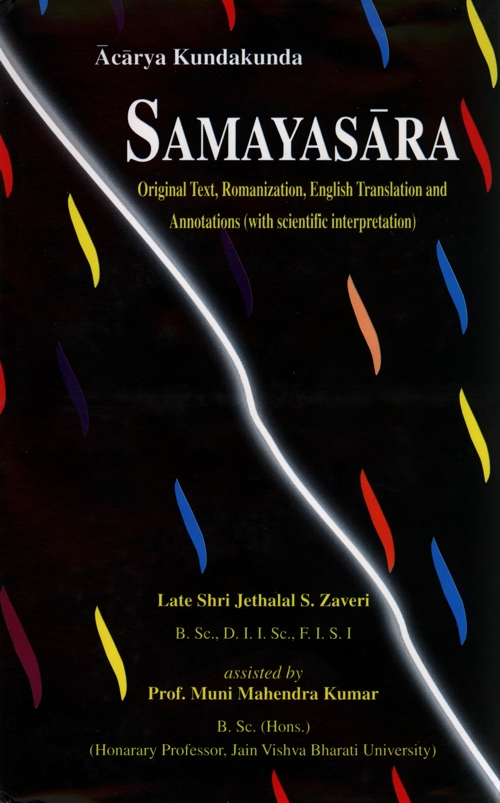

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar