| 8th International Conference on Peace and Nonviolent Action |

Part I: Buddhism

Introduction

Thailand is known as a Kingdom of 67 million scattered in 77 provinces in the Southeast Asian region and well known for its Theravada Buddhist culture. Although Thai is the only national and official language of the country, the population of Thailand is, however, mixed from various ethnicities, i.e., Chinese, native Thai races of various parts of the country, Malay, Indian, etc. Thailand has turned democracy in the 1932, and even after 80 years the country is still struggling to develop its own style of democracy.

Violence from terrorist activities in the deep south of Thailand are almost routine whereas development of civil society is still retard process as the country still need more people to get involved in almost every part of the public sectors. NGOs and charity organizations are doing their best to mobilize the people to do charity works and taking part to serve as public volunteers.

Currently, Thailand ranks 102 in 177 countries in term of corruption by Transparency International (December 2013), and the downward trend is continuing in spite of its strong religious background in morality. The country has difficulties in recruiting volunteers to work in various public sectors. Educationally, Thailand’s education is ranked 8 among 10 members of the ASEAN countries by World Economic Forum (2013). Social problems such as prostitution and human trafficking, are ubiquitous. The gap between the rich and the poor has been widening.

Worse than that is the fact that Thailand is in the worst political crisis that it has ever seen since 1932, when the country turned from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy under "Democracy". Thailand is torn apart by two polarities of political power: the Red Shirts and the Yellow Shirts. The point of division is the attitude towards Mr. Thaksin Shinawatra, a former prime minister of Thailand. The Yellow Shirts attack him as being the devil of capitalistic democracy whose corruptions have created huge damage for the country, whereas the Red Shirts see him as the savior for the poor and the marginalized. Thailand has experienced years of public protests and several uprisings and marathon political campaign which seem and endless and so far have not lead to any reconciliation.

A solution for the country is to empower people to take part in civil services, and the inspire them to dedicate themselves to volunteer work, and to give feedback and those who work more would benefit more from the society. A system that brings a solution should also be rooted in the Thai Buddhist culture, and it should be efficient and fair enough for people at the grass-root should to join in and be empowered to contribute more for the public good - which includes harmony among people of different faiths.

Worldviews of Buddhism

The Buddha describes the cosmos as a huge space, dynamic but uncreated. It is composed of thousands of world-systems (lokadhātu), each has its own sun, moon, stars, and the unseen worlds of angelic beings and demons of numerous kinds. According to this description, the Earth, therefore, is not the only planet inhabited by humankind, animals and plants. Each being is an individual which is repeatedly born and dies in the endless rounds of transmigration, the so-called Saṁsāra. This non-geocentric attitude is common and presented in different schools of Buddhism. From time to time, a being who has accumulated sufficient virtue and wisdom becomes enlightened and known as the Buddha. He then declares the same teachings and forms the same kind of community that the historical Buddha, Siddhattha Gotama [Siddhārtha Gautama] has done. At any point in time, the cosmos always has a number of Buddhas preaching in different parts of the vast universe. Some schools of Buddhism do not worship the historical Buddha as much at the cosmic ones. One school in particular, known as the Pure Land Buddhism, worships the Buddha of Infinite Life (or Infinite Light), who created his own paradise known as the Western Paradise as the center of Buddhist faith.

Every school of Buddhism agrees, in all aspects, with the historical Buddha, that an individual can finally become enlightened as a Buddha. Someone who determines to win this highest state of enlightenment in his/her last existence is called a bodhisattva in the Theravada schools. The Mahayana Buddhist tradition, in particular, makes it almost compulsory that everyone take this ambitious spiritual goal, whereas the conservative Theravada upholds that people can be different and have the right to determine their final liberation on their own terms.

According to the Buddha, there is no eternal damnation, regardless of how serious the crime one might have committed. However, an individual may suffer an extremely long retribution of malicious experiences in purgatories, and these can also lead to a series of rebirths in woeful conditions in the afterlife. Nevertheless, after paying off the bad debt of the bad actions (karma), the person is subject to be born again in the human condition. Nirvana is the only eternal resting-place, which is reality when all karmic debt built up during the subject's existence is completely paid off.

The Buddha refused to discuss the issue of the Prime Cause, the Last Days and the existence of the Self after Nirvāṇa, simply because they are beyond the limits of human understanding and therefore impossible to prove. However, he affirmed that the Dharma or the doctrine that the Buddha founded is subjective and available for everyone to experience. Once liberation is attained, one’s mind would be free to probe the mystery of the universe. The Buddha’s enlightenment on how to attain the Dharma can be taught to, and learned by others. Therefore, the religion, according to the Buddha, was not subject to belief, but to experience and proof through one’s own effort. This logic of teaching is in line with that of modern science.

Diversity of interpretations in Theravada Buddhism

Teachers and experts in Theravada Buddhism have diverse opinions on the priority of precepts and practice to follow in Buddhism. Buddhists who see Buddhism as a school of spiritual liberation, gravitated towards the attainment of nibbāna or nirvāṇa, the so-called Nibbanic[1] Buddhism, which would limit the goal of their life merely to the pursuit of spiritual liberation through the Eightfold Path as a part of the Four Noble Truths. Accordingly, they see that life is full of suffering, and the only way to make a true progress in life is to detach from everything, merit and demerit included, as their goal of life is not to be reborn again in whatever condition.

However, another group of Buddhists would argue that this might not be sufficient, as they see the Karmic Law as authoritative. Their goal of life is to accumulate the maximum merit for great achievement of their life and the lives to come. Merit is the real spiritual treasure that they could take with them to the afterlife, whereas demerit is the opposite. According to this group of Buddhists, the true meaning of life is accumulation of merit for themselves. Most Buddhists who belong to this latter school of through would prefer to limit their merit making on the community of Buddhist monks and not to the poor or the needy as they are not the most fertile soil for merit making.

Another group of Buddhists ground their faith in the coming of the Fifth Buddha, the Lord Metteyya, who is prophesized by the Buddha in the Book of the Long Sayings of the Buddha that he would be enlightened after the world passed through a period of global catastrophe. According to the sutra, the Lord Metteyya [Maitreya] will be the Fifth and the last Buddha of the world who will preach the exact same doctrine as the Siddhattha Gotama did, and will put the world in the true balance when life span of a human being will be 80,000 years[2].

For the latter group of Buddhist, the course of the world is already predestined and is no subject to any change. Individuals, however, may dedicate the life in search of a special panacea to rejuvenate their life to meet the Lord Metteyya.

These three interpretations of Buddhism are all grounded on Buddhist canonical literature of the Theravada tradition. They accept the same authority of the Tipiṭaka and take refuge in the same Buddha, but the difference lies on their priority of the section of the text of reference. All would agree on the same model of reality, and the attribute of the Buddha.

According to the Buddha everyone is basically equal

The Aggaññasutta,[3] one of the major aphorism in the Book of the Long Discourses of the Buddha, so-called Dīghanikāya, of the Tipiṭaka[4] (Tripiṭaka) is a good reference to the transcendental origin of the human race which later developed into society and caste system of ancient India. The story was an allegory of a dialogue of the Buddha with two Brahmin postulants who were looking forward to be ordained into the order of Buddhist monks.

According to the Buddha, the human race is descendants of genderless, self-luminous celestial beings who were trapped on earth because of their temptation. Having lost their supernatural ability, they suffered from series of environmental decay resulting from their prejudice. In order to prevent further fall, they elected the first king, Mahāsammata or the People’s Choice, as their ruler who would have authority to keep justice and to penalize those who should be penalized.

The influence of the sutra in Buddhist culture is seen in a shortened version of the word sammata still used in Burmese language for the position of the elected president of a state.[5]

Based on the story, members of the human race are all equal, and there is no privilege of men over women or vice versa. Moreover, the power of the king or government comes directly from the people. Prejudice based on the color of the skin is not acceptable as it was the cause of environmental decay, and seen as one of the earliest sins that the ancestors of the human race have committed.

Scholars on Buddhism interpreted the story as an alternative version of the famous Hymn of Creation of the Rigveda where castes are respected as fundamental to the creation of the universe. Also, the system of election was used among the members of the Buddhist order where opinion of each member was respected equally, and the entire story of the sūtra was written based on Buddhist monastic culture and discipline of monks. Historically, the sutra shows the way early Buddhist community solved their problems through convention where each monk has their equal right to express their idea.

In Buddhist culture, however, the authority of the sutra is strong, as it has been used in Burma. It is one of the most commonly quoted sources for the principles of democracy in Theravada Buddhist culture that explains the root of equality of the people and authority of the government. Although the Buddha never described the Utopia of Buddhists, but the sutra remains supportive of equality of individuals, and against division of the humankind into castes or even nationalities. The message of the sutra is clear that we are all members of the same race from the beginning and all of us deserve respect and rights that are endowed upon us as a part of the Nature.[6]

Towards a peaceful society: Building up of civil society

Although Buddhism has numerous teaching of the cultivation of inner peace and self development, the Tipitaka[7] [Tripiṭaka] the Buddha never mentioned about ideal system of administration or what Utopia is. Moreover, none of the traditional interpretations of the so-called Nibbānic, Kammātic[8] nor Millennium Buddhism has much interest in social and global issues. Practicing Theravada Buddhists trend to be uninterested in social problems and non-religious conflict.

However, there is one of the earliest Buddhist sutras called the Maṅgalasutta or the aphorism on the Good Omens which I believe that could be generally used as another way of interpretation of Buddhism and directly related for the building up of peaceful society. Traditionally, the sutra is popular among Buddhists as a part of the Paritta chanting, which is recited by monks and nuns at most auspicious celebrations and festivities.

In its context, the sutra is a dialogue between the Buddha and a deity who came to inquire about the nature of Good Omen which had been issues of debates in heaven and earth for years. The Buddha then expounded the 38 Good Omens that offers a holistic approach that helps us understand Buddhist social ethics, which are foundation of civil society.

The Maṅgalasutta[9]

The term "Maṅgala" is a Sanskrit word and shared with Pāli. It directly refers to a belief in traditional society that before an episode of a significant event, there is a sign that foretells the incidence. The belief is common even in our modern life. Each tradition has it own way for interpretation of "Maṅgala". For example, in some society emphasis is on the color of the dress a person is wearing, or the character of the body parts, or location and appearance of a house which influences the future of the owner.

In the Maṅgalasutta, the dialogue is given in 12 verses. In the first verse, the deity states its intention for the visit. The Buddha’s response is all of the following verses, beginning with: do not associate with a fool (First Maṅgala), associate with the wise (Second Maṅgala), worship those who are worthy (Third Maṅgala). Each verse, except for the last, ends with a phrase, "This is the highest Good Omen."

Summary of the Maṅgalasutta according the verses from the Sutta-Nipāta

Verse 1: Verse 2

- Legend in short

- Questions of the deity to the Buddha

- No association with the fool

- Association with the wise

- Worship of the worthy

Verse 3

- Good environment

- Having formerly done merit

- Having established “self” in the right course

Verse 4

- Great learning

- Skill/arts

- Mastering of discipline

- Well-spoken words

Verse 5

- Taking care of parents

- Taking care of children

- Taking care of spouse

- Organized livelihood

Verse 6

- Giving

- Practicing virtue

- Taking care of relative

- Blameless activities

Verse 7 Verse 8

- Abstinence from evil

- Abstinence from intoxication

- Vigilance in duties

- Respectfulness

- Humbleness

- Contentment

- Gratitude

- Listening to the Dhamma

Verse 9

- Forbearance

- Sensitivity

- Seeing religious persons

- Timely dialogue in religious issues

Verse 10

- Austerity

- Practicing holy living

- Seeing the Noble Truths

- Realization of Nirvana

Verse 11

- Unshaken by vicissitude

- Free of sorrow

- Free of defilement

- Secure Mind

Verse 12

- The person, having done all of the above, wins everywhere, successful at all time; this is the Highest Maṅgala.

Philosophy of the Maṅgalasutta: A Holistic Model of Buddhist Development

The Maṅgala[10] Sutta is probably the only systematic interpretation of Buddhism. It shows the coherence of Buddhist precepts and practices for spiritual development. It shows that the Buddha lived his life according to the Maṅgalasutta, and practiced what he preached.

The twelve verses of the Maṅgalasutta offer a holistic approach to Buddhism. The Maṅgalas or Good Omens are not arbitrarily arranged; they are systematically related to one another. Beginning with the most external and physical, it gradually introduces us to various ethical principles and guidelines for living life as a good person, up to the most advanced quality of mind (the mind which is free from sorrow, free from defilements, and secure).

The concept of Maṅgala is directly related to prosperity in the future. One interpretation is that the aphorism is an ethicized version of Indian superstition which evolved when the early community of monks and nuns were actively engaged in local culture.

The sutra also shows the practical relationship between one Buddhist principle to the other, which allows one to see an entire process of spiritual development. Also, each Maṅgala, once practiced can lead to the higher ones. Maṅgala also connects social ethics, such as responsibility to parents, children, spouses, friends and relatives. Hence, the connectedness of each member of the society is also seen.

Since the meaning of omen links the present to the proximate future, we can see the relationship between social and personal ethics related to the common good of society. In another words, individuals in the Maṅgalasutta are not isolated, but are bound to one another by morality which when practiced, will bring the common good to everyone. Through the lens of the Maṅgalasutta, vice in society is a bad omen. It will corrupt the society, and cause a spiral of decay. It is the responsibility of every member of the society to take action and reverse the bad omen.

The interpretation is also based on the model of Dependent Origination (Paṭiccasamuppāda [Pratityasamutpāda).[11] Our lives are conditioned by others, and our success or failure comes from conditions associated with our moral actions. Once one maṅgala is performed it also conditions another maṅgala to come into existence. And when all maṅgalas are practiced, happiness and success in life are assured. Therefore, the aphorism is a systematic teaching of social ethics in Buddhism, and provides a social dimension of society where happiness and success in life depend upon an individual’s morality. The collective good of individual members in society assures the common happiness and success of everyone.[12]

Buddha through the lens of the Maṅgalasutta: An agent for world transformation

Through the lens of the Maṅgalasutta, the Buddha can be seen as an ideal person. He perfected all the Maṅgalas in his life, and he is indeed the First Good Omen of the World. In Buddhist legend, the Buddha was formerly a Bodhisattva who had accumulated an enormous amount of merit in his past lives, which were enough to enable him to win Supreme Enlightenment in the fifth maṅgala in the aphorism.

The Buddha’s moral decision to renounce his princely life was a blessing, which allowed him to fulfill his spiritual quest. The life story of the Buddha reveals to us all 38 good omens practiced by the Buddha on different occasions. Each moral decision made by him was supportive of other blessings. Together they fostered changes in society.

The Buddhist community was founded and committed to propagating the teachings of the Buddha to encourage spiritual civilization in humankind. Prince Siddhartha’s renunciation in his pursuit of Enlightenment is seen as another blessing, although some may criticize him for not being a good husband or father. Yet the Buddha never completely abandoned his responsibilities as a husband and father. He returned to his family after he had accomplished his objective. In this sense, he fulfilled all the blessings as he revealed them in the aphorism and elsewhere in the Pali canon. Judged by the teaching of the Maṅgalasutta, the Buddha practiced what he taught and did not behave otherwise. Therefore he is sincere spiritual teacher and his life is the embodiment of his teachings.

The Maṅgalasutta and Development of Democracy

Although nowhere in the Buddhist cannon does the Buddha give a definition of a society or what an ideal society looks like, it is clear that when the members of the society are practicing the Maṅgalas they are actively engaged in social development. The teachings of the Buddha are not merely for the sake of attaining Nirvana. They are also conducive to the collective good of everyone in the world, as society improves by its members being devoted to decreasing suffering.

Since Maṅgalas or good omens are signs related to the future, they create a perception of society as dynamic. Its progress or failure depends upon the common good for every member of the society. In other words, a society is the Commonwealth of Morality of individuals. The virtue that one has accomplished maintains and mobilizes society in a good direction.

Moreover, the 38 Maṅgalas in the sutra are not gender specific or limited to particular social status. They can be applied collectively in every part of the society. Maṅgalas for lay people are also good for the ordained; Maṅgalas for men are also good for women, and vice versa.

Through the lens of the Maṅgalasutta, a society is not merely a gathering of separated and isolated individuals; people are all inter-connected with one another and with the environment. A civil society is a society which is therefore respectful of law and order, where its members are good friends to one another, and are actively engaged in various kinds of activities, academic, arts and science, literature, philosophy, religion, etc. They are also responsible for one another, the environment and social welfare.

For Buddhists, the sutra on the good omens provides a holistic and systematic interpretation of Buddhism, under which a spiritual life cannot be lived alone, but depends upon one another. The aphorism also supports inter-religious dialogue which is not seen as optional for Buddhist spiritual development, but essential to the true practice of Buddhism, i.e. by knowing other faiths you know more of your own.

According to the message of the Maṅgalasutta, religious leaders should be working together and offer the strongest message in support of human dignity. Rather than arguing which religious institution is the strongest or the best, let's propose that the strongest ones are in a position to do the most good. Thus, each religion may play its part in working together for peaceful world and society.

Part II: Suggested Practical Guidelines for Strategic Plans

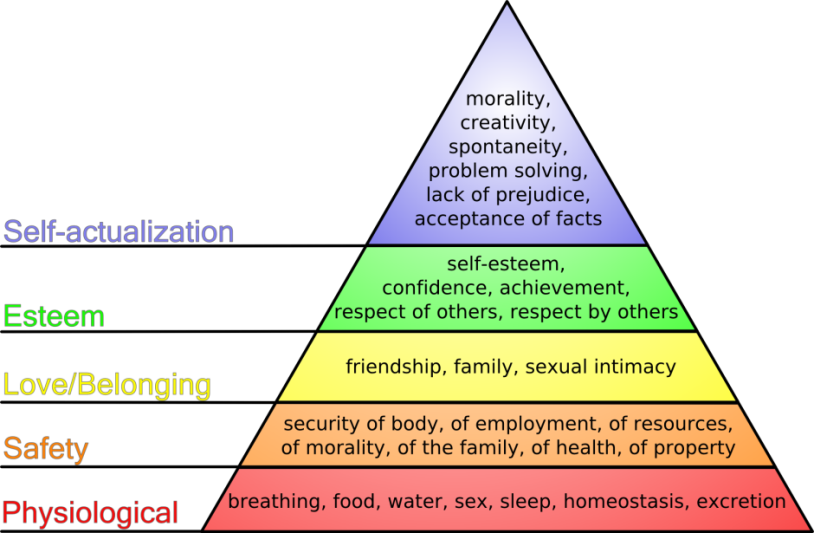

With the blessing of the Internet and computer technology, it is plausible to apply the technology for social mobilization and human resource development. Based on the works of Abraham Maslow who is the authority in psychology of inspiration, the Mangalasutta could be applied together with the framework of the hierarchy of needs as described by Maslow.

Fig 1 Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow 's hierarchy of needs shared a lot of similarity with the arrangement of Mangalas in the aphorism. The concept of the good omens he has taken for granted as the basic human need, i.e. physiological, and safety; the Mangalas in the first verse agree with the third level addressed by Maslow. Those in the later verses correspond with the building of esteem and self-actualization, practically in the same line in the hierarchy of needs of Maslow.

Citizen Smart Card

In Thailand, where the citizen's ID card is linked to the computer networks of the government, it can relate to a national scoring system for achievement of each registered citizen. The smart card is distributed freely to every citizen of Thailand from the age of seven. The network already has profiles of all citizens of Thailand. However, the database is accessible by government officers, and not the citizen; the law also protects the rights of each citizen.

Additions to the profile of social credit can be created online and open to public. Registered persons can open their own profile for credit which weighs their social contribution related to projects of public good, based on the philosophy of the Mangalasutta in Buddhism, every act of goodness and society is the Commonwealth of Morality. According to this principle, everyone is responsible for the good and the bad done by other member of the society.

In the myth of the judgment of the dead in the historic book of Traibhūmi-kathā (the Three Worlds According to King Ruang), composed in A.D. 1345 by Phaya Li-thai one of the most famous kings of Sukhothai-Srisacchanalai. All the good and bad karmas of every man and woman are recorded and used for judgment by the God of Death.

Fig 2 Mechanism of social credit

Rooted in this historic book, the social credit system can be accepted by the people of Thailand and other Theravada Buddhist countries, as a way to promote morality and human resource development. However, the system cannot work without public acknowledgments and trainings suitable for carrier path development of each citizen.

From this system, children in rural areas and remote villages can have access to the program online with consent of their parents. The system is, however, not mandated for every citizen, but optional. Once a citizen have open their profile of social credit, their scores and activities performed will be registered. The scores of achievement have to be transparent and transparent to public reviews. The scores are subjective and cannot be transferred. They are direct merits of the volunteers. The government, however, has to establish its national institution to validate the scores.

The system can open up new territories of volunteer activities and human resource development. For example, medical schools can use the score to merit candidates for entrance examination wherein a certain number of hour s/he works of volunteer services in hospitals or community healthcare centers are required for application to be a medical student, nurse, dentist etc. Trainings are also required to fulfill the need of the volunteers; they can be seen as a reward to the volunteers who have made certain achievement. With the social credit system, the government can inspire hope and dream for a better future of the youth and children, as well as enhancing human resource development. More people will participate in political, religious, and humanitarian, and environmental activities.

In certain urgent public problems such as conflicts of faiths among religious people, the government can create incentive for youth groups to join special training programs that promote peaceful dialogues among religions.

Combined applications of Buddhism and Maslow’s hierarch of needs can work together for human resource development and various social volunteer activities with the help of IT and smart card under the rubric of "Social Credit System".

Conclusion

As a leading Buddhist country, the government of Thailand should facilitate new social technology that could be applied to galvanize sustainable development through inspiring its own people to get involved in volunteer works. One of the options is through the use of the Internet, and applied with citizen ID card that links the volunteer activities to a scoring system which is accessible and traceable by the public. The scoring system can be designed to be just and fair. Since the card is issued to every citizen of Thailand from the age of seven, the moral promotion program can begin with the scoring system for every child from the age of seven onwards.

Areas of children's participation can include all non-academic activities such as tree plantation, public services, and all public volunteer activities. Based on the theory of the hierarchy of need of Abraham Maslow, the project will satisfy the third need of the child, and connects it to the level of esteem building where s/he can make more achievement and success. The Internet can give immediate results to the activities. Of course, it must have checking system to endorse the activities that they have been done as registered online. The social credit system can be a powerhouse for the development of democracy, human rights, and human dignity and harmony of different faith groups. It also gives a model for community healthcare development which advocates active participation of every members of the community in caring and nurturing one another. The system will not only decrease the requirement for government funding but also potentiate the quality of care for members of the local communities.

References

- Material of NSDS Project at AIT/UNEP PRC.AP

- Mettanando Bhikkhu, (1994) A Buddhist Perspective on Population Development, World Conference on Religion and Peace, published for UN Conference on Population Development, Cairo, 1994.

- Mettanando Bhikkhu (2007) Dhamma-Osot (The Medicine of the Dhamma in Theravada Buddhism) on the exegesis of the Maṅgalasutta, Bangkok (in Thai)

- Mitchell D W (2008) Buddhism: Introducing the Buddhist Experience, Second Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Myanmar-English Dictionary (1994): Dept of Myanmar Language Commission, Ministry of Education, Union of Myanmar

- P A Payutto, (1995) Dictionary of Buddhism, Mahachulalongkorn University Press, 2538 BE, Bangkok.

- P.A. Payutto (2001) Buddhist Solutions of the Twenty-first Century, translated and compiled by Bruce Evans, The World Buddhist University, Sahadhammika Co. Ltd., Bangkok.

- Saddhatissa, H (1997) Buddhist Ethics, Wisdom Publications, Boston

- Son, J (2003) Invisible Borders: Reportage from Our Mekong, IPS Asia Pacific Centre Inc, Bangkok

- Son, J (2005) Bustling Borders: Reportage from Our Mekong, IPS Asia Pacific Centre Inc, Bangkok

- Son, J (2006) Crossing Borders: Reportage from Our Mekong, IPS Asia Pacific Centre Inc, Bangkok

- Son, J (2007) Opening Borders: Reportage from Our Mekong, IPS Asia Pacific Centre Inc, Bangkok

- Son, J(2009) Changing Borders: Reportage from Our Mekong, IPS Asia Pacific Centre Inc, Bangkok

- Spiro, M E, (1984) Buddhism and Society: A Great Tradition and Its Burmese Vicissitudes, 2nd Expanded Edition, University of California Press, California, Berkley.

- Sutta-Nipata, Translated by V. Fausboll Oxford, Claredon Press, 1881.

- Swearer, D K (1995) The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia, SUNY, New York

- Thailand Environment Institute, UNEP (2008), "Greater Mekong Sub-region Sustainable Strategy" draft as of 2007.

- Uchikawa, Shuji, (2009) Major Industries and Business Chance in CLMV Countries, Bangkok Research Center, IDE-JETRO, Bangkok

- Walshe, M. The Long Discourses of the Buddha, A Translation of the Dīgha Nikāya, Boston, Wisdom Publication, 1995.

- Denis O'Connor (2007). "Maslow Revisited: Constructing a Road Map of Human Nature", Journal of Management Education, Vol.31, No.6, December 2007 738-756 DOI: 10.1177/1052562907307639

- Frederick D. Harper (2003). "Counseling Children in Crisis Based on Maslow's Hierarchy of Basic Needs", International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling, Vol. 25, No. 1. March 2003, Kluwer Academic Publishers

- Grace Onchwari (2008). "Teaching the Immigrant Child: Application of Child Development Theories", Early Childhood Education Journal, 36.267-273, online publication, Spring Science+Business Media, LLC 2008

- M. Deborah Larimer (2008). Authentic Education and the Innate Health Model: An Approach to Optimizing the Education of the Whole Person, Dissertation submitted to the College of Human Resources and Education, West Virginia University for Doctor of Education in Educational Psychology, Morgantown, West Virginia.

- Susan Dawson (1992). The Focus group manual: social and economic research (SER). Geneva: WHO

- Wayne F. Cascio (2005). Applied Psychology in Human Resource Management. Boston, Pearson. (7th ed.)

Mano Mettanando Laohavanich

Mano Mettanando Laohavanich