Whilst it is quite possible to lead a religious life as a lay person, complete devotion to religion involves giving up completely the concerns of ordinary life.

In most religions we find groups of people, usually fairly small in numbers, who leave home and family and occupation to live dedicated lives as monks or nuns.

We are told that Mahavira organized the Jain community into four sections, monks or nuns, who can follow his teachings to the fullest extent, as well as lay men and lay women. Monks and nuns make up, of course, only a small part of the Jain community but they are a very important part.

For a religion which has no priests, the monks and nuns serve as religious teachers. Most of the great Jain scholars of the past were monks and even today, when there are also considerable scholars amongst the ranks of the Jain laity, many of the important works on Jain religion are written by monks.

Monks and nuns set an example of the religious life for lay people: Their duty is their own souls' spiritual welfare and that of others as well. They are greeted and treated with great respect and it is an act of merit for the householder to feed them and otherwise provide for their needs.

They possess no property beyond the bare essentials, a couple of pieces of cloth for clothing (monks of the Digambara division of Jainism do not even have these and go completely naked), a bowl, walking stick, a soft brush to remove insects gently, and one or two other objects, together with books and writing materials. Their daily needs are supplied by the faithful.

Although it is permitted that a boy who shows exceptional promise for the religious life may become a monk as early as the age of eight, most people will be adults, or at least in their teens, when they do so. Indeed it is quite common for middle-aged people to enter the mendicant life. The prospective mendicant must be free from physical infirmities and moral short comings and will seek the permission of parents or guardian. The candidate will seek out a guide and teacher (guru) in the order who will make sure that this person is suitable in every way and who will remain his mentor throughout life. The diksha or initiation ritual will be the occasion for great ceremony, when the candidate renounces his worldly possessions and receives the essential items for his new life. His hair is plucked out in imitation of the act of Mahavira when he renounced worldly things. Now the initiate receives a new name to show that he has completely left his home and family and all his earlier life. Family life, business, politics, are no concern of the Jain monk or nun. For the first year or two the novice will receive training in the rules and practices of monastic life before being confirmed in his or her vocation.

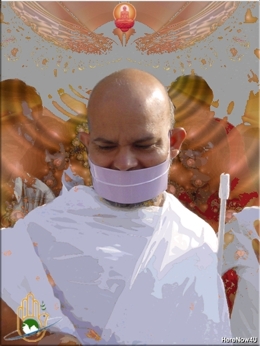

The sadhu or sadhvis bound to keep the five great moral precepts in their fullest rigor. Non-violence involves for the mendicant the most meticulous care to avoid harm to even minute creatures which have only one sense, the sense of touch. (It is recognized that a layman can not always avoid harm to these.) This can involve softly sweeping the ground if necessary to clear living creatures, carefully removing insects, and sometimes using a cloth over the mouth to avoid harm to the most subtle beings of the air. The vows of truthfulness and non-stealing are interpreted in the strictest manner: the mendicant may not take even the most trivial object without its owner's permission. Sexual restraint is total; non-acquisitiveness means the virtually complete abandonment of material possessions.

The person who has adopted the mendicant life should cultivate ten qualities. First comes forgiveness of those who have done harm and avoidance of anger. Then there are modesty (not least the avoidance of pride in one's spiritual achievements), avoidance of deceit or concealing one's faults, contentment and the avoidance of greed, teaching others the high ideals of the scriptures, watchfulness to avoid harm to living beings, undertaking austerities without hope of material reward, avoidance of tasty food and comfortable lodging, complete renunciation of the desire for possessions, and lastly careful restriction on association with members of the opposite sex. Self-control, and vigilance in every daily action to avoid harm, are the two chief virtues.

The daily life of the sadhu or sadhvi is ordered and regulated. The monk rises from his simple bed hours before dawn. He says the Panca Namaskara, the fivefold formula of obeisance to the superior beings. He greets his teacher respectfully. A period of meditation follows, after which he recites the rituals of penance or confession (Pratikramana) for any violence or misdeeds he may have committed. He checks his clothing carefully and removes any small creatures which might get harmed (and he will do this at least twice a day). By this time the sun will have risen and he can spend a couple of hours in studying the scriptures (for a monk does not use artificial light). The teachers will give sermons for both monks and laity. Then [those Jains who worship idols] will go to the temple to worship the Tirthankara. Detailed rules regulate the way in which monks and nuns may seek their food: they should go each day to different houses and will accept only food which is willingly given and not specially prepared for them and, of course, which is acceptable in terms of the Jain monastic vows. On returning from the trip to seek food the monk will present the food before his teacher and will share it with other monks who, from sickness or other cause, cannot themselves seek food, before he takes any food himself. The afternoon and evening are devoted to further study and meditation as well as the small tasks like writing letters which even a mendicant will have to do. There will be a second trip to seek food in the late afternoon so that the meal may be eaten before nightfall. The day ends with a further visit to the temple, a further ritual of contrition, and the monk goes to bed after vowing forgiveness to those who have harmed him and seeking forgiveness from all. The life of a sadhu or sadhvi (nuns follow the same routine) is hard but they learn to overcome hardships and face them resolutely and with detachment.

The spiritual life of the Jain has been likened to a ladder. There are fourteen 'rungs' or stages (gunasthana) on the ladder. These have been described in great detail in the scriptures. To start with the individual has not even begun the ascent and has totally wrong attitudes. If the individual can get rid of delusions then the soul succeeds in going straight to the fourth rung of the ladder but the position is still precarious and it is possible to slip back onto two different levels of wavering states and even right back to the beginning. But if the individual can control passions, desires, hatred to a reasonable extent (not retaining them beyond the annual self-examination in the Paryushan season of the Jain year) the ascent is begun. He or she will now feel a tranquility of spirit, will have the ability to discriminate between right and wrong, will want to avoid purely material pleasures, will be kindhearted to others and will have a clear vision of truth. Such attitudes will naturally lead onto undertaking to obey the five great moral precepts, and this will be the next rung on the ladder. We saw in the previous chapter how the lay person reduces his or her attachment to the things of the world and develops attachment to religion. That process happens at this stage or rung on the spiritual.

The sixth rung on the ladder marks a great decision for now the individual has progressed so far that he or she is intent on renouncing the world and adopting the life of a monk or nun. Henceforth life is totally directed towards spiritual progress. The great vows are followed in their entirety and the individual reaches the stage of eliminating all the stronger passions. Daily self-examination and sorrow for offences committed knowingly or unknowingly is now obligatory and the individual who succeeds in the discipline of the sixth stage rises further to the next rung. Passions are virtually subdued but alertness is still needed to prevent slipping back. The aspirant climbs three more rungs, at each stage gaining more complete control over himself. The eleventh rung is unsafe: even now, nearing the top of the ladder the individual soul can drop back, desires and hatred can arise again and the slow climb must be restarted. Some individuals, very few at any time, reach the twelfth stage. Delusions and desires have been eliminated and the way is clear to the thirteenth rung when the soul achieves complete enlightenment, total knowledge. The fourteenth rung detains only momentarily the enlightened soul which passes quickly over it to achieve moksha or total liberation.

This is a long process. Every individual soul passes through countless lives. Sometimes progress is made, sometimes not. The mendicant who sets himself or herself resolutely towards spiritual development still has a long way to go. Even when self-control is almost achieved and delusive views of the nature of life and the universe have disappeared for the few who reach the stage described as the tenth rung on the ladder, the completion of what can be described as the constructive stages of the mystical life, even then the old suppressed passions can re-emerge and the final goal recedes as the soul drops back into old habits, old feelings, old delusions.

Throughout the development of the spiritual life the individual will have before his or her eyes the example of the Tirthankara. According to Jain tradition, in each of the great cycles of time, lasting countless thousands of years, some people gain total enlightenment. Of these, twenty-four in each half-cycle are known as Tirthankara. They are the ones who, having achieved total knowledge themselves, pass on knowledge in teaching the people, before they leave the world and attain the ultimate state of moksha. Mahavira was, of course, the twenty-fourth Tirthankara in the current half-cycle of time. At all stages of the religious life the Tirthankara are seen as a help to the aspiring soul, they are the nearest thing Jainism has to a god, in fact they are sometimes even called 'god'. In a Jain temple the image of the Tirthankara is worshipped and treated with great devotion and respect.

But the individual must understand that the Tirthankara is to be taken as a supreme example of spiritual struggle and success, not as the donor of favors or the author of fortune or misfortune.

The individual must work out salvation for himself but it is a great help and very meritorious to meditate on the example of the Tirthankara (whether in the presence of an image or without that material figure before the eyes), to take the Tirthankara as an ideal and to resolve to follow the path the Tirthankara has shown.

Dr. Paul Marett

Dr. Paul Marett