Anuvrat International Conference

Impact of the Aṇuvrata-Movement on Indian Society and Global Prospects

Question

Why did the aṇuvrat movement not have the desired effect on Indian society at large during the 65 years after its inception and may suffer a similar fate if propagated across the globe - despite the instant appeal of the proposed moral rules?

Brief History

- Sermon on the Atombomb/Hiroshima, 6.9.1945 Sardarshahar

- “A Message of Peace to a World full of Unrest,” 1945

- Aṇuvrat Saṅgh, 1.3 1949 Sardarshahar

- “On the Threshold of Good Life (The First Manifesto of the Anuvrat Movement),” 1949

- Aṇuvrat Āndolan, 1954

Condition of Participation

“The only qualification that the movement recognizes is the preparedness on the part of the person concerned for self-restraint and self-examination”

Aim: Eliminating the Roots of Social Violence

“Marx discovered that the root of a change in society lay in the change of the economic system. Acharyashree is trying to discover the root of a social change in the transformation of man's nature” (Mahaprajna)

Means

“Even an atom of a vow can emancipate a man from the greatest fear. - The vow is the dividing line between one individual and another. It is a restraint a man subjects himself to willingly and not something imposed from the outside [...] religion in essence ought not to be grounded in rituals but in the building of character”

Ācārya Tulsi’s Social Reform-Programme

Finding social solutions “without violence and exploitation”:

- Reduction of greed though limitation of grabbing-instincts.

- Reduction of the number of beggars through limitation of charity to beggars.

- Redistribution of land, organisation of cooperatives and common exertion of all members of society.

- Organisation of a just redistribution of ressources by the class-distinctions transcending state.

The Terāpanth-Aṇuvratas

“… underwent changes in the context of social problems” (Mahāprajña 1987)

Basic Principles of ‘Dharma’

- Dharma occupies the first place, sect comes next.

- There may be many sects but dharma belongs to all.

- Dharma is quite distinct from politics. It must not be subjected to political interference.

- Dharma is not merely an instrument of ensuring happiness in the hereafter. It should also bring happiness in the present life.

- He who fails to make his present life better is unlikely to achieve happiness in the hereafter.

- The primary aim of dharma is to purify character. Its ritualistic practices are secondary.

Nine-point scheme

- not to think of committing suicide;

- not to use wine and other intoxicating drugs;

- not to take meat and eggs;

- not to indulge in a big theft;

- not to gamble:

- not to indulge in illicit and unnatural intercourse;

- not to give any evidence to favour a false case and untruth;

- not to adulterate things nor to sell imitation products as genuine and

- not to be dishonestly inaccurate in weighting and measuring.

Thirteen-point scheme

- not to intentionally kill moving, innocent creatures;

- not to commit suicide;

- not to take wine;

- not to eat meat;

- not to steal;

- not to gamble;

- not to deposit falsely;

- not to set fire to buildings or materials out of malice or under temptation;

- not to indulge in illicit and unnatural intercourse;

- not to visit prostitutes;

- not to smoke and not to make use of intoxicating drugs;

- not to take food at night, and

- not to prepare food separately for Sādhus.

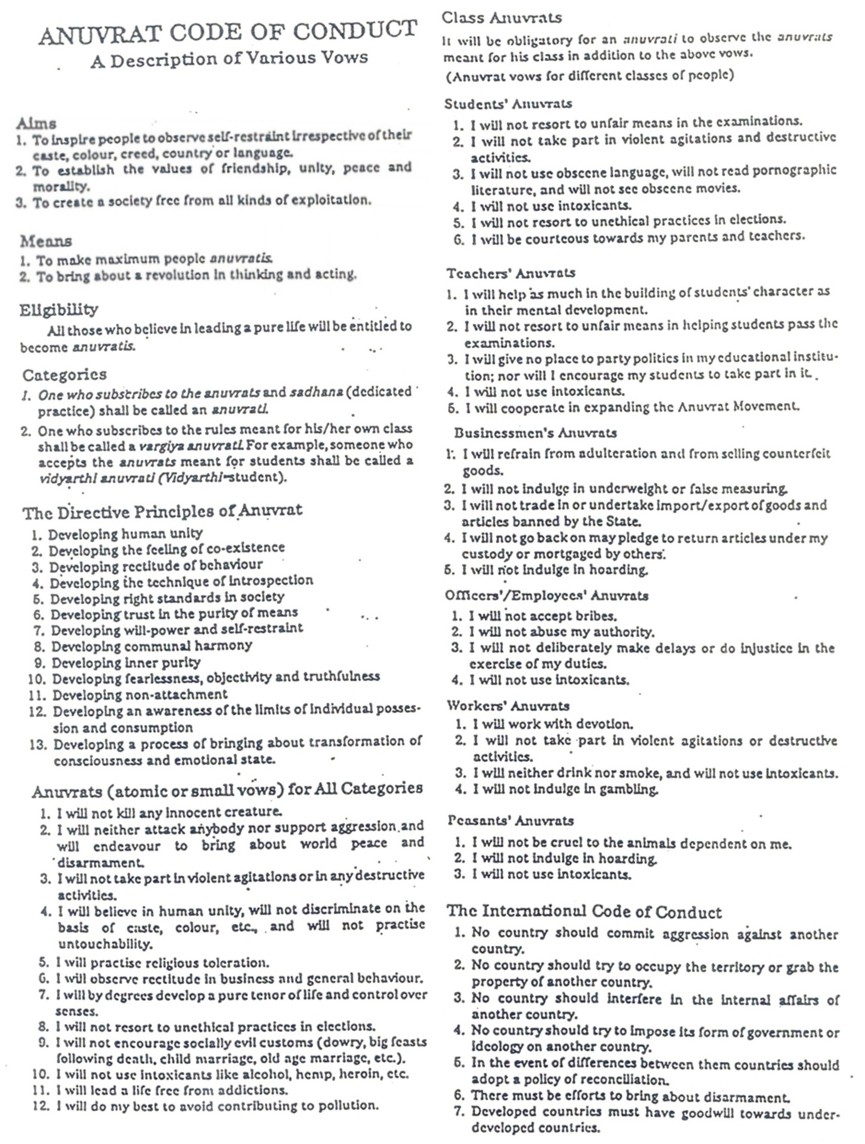

A Description of Various Vows

Aṇuvratas for Writers

- I will create literature and/or art not for commercial gain, but only with the feeling of producing it, symbolising truth, goodness and beauty.

- I will not produce obscene literature and/or art.

- My creation of literature and/or art will not be affected by party politics and communalism (Misra).

Observations on the Form of the Rules

- The (9-13-11) ‘universal’ aṇuvratas have been modelled on ‘specific’ rules of Jaina lay-ethics with an added emphasis of intoxication (cf. Buddhism’s dasa-sīla)

- The scheme combines preambles, positive directive principles and prescriptive negative rules in a hierarchical scheme.

- The acceptability of the rules by non-Jains has been rendered possible by the abstraction from guru, dharma, saṅgha (‘Jainism without karman’).

- The originality of the various versions of the list are the rules addressing general problems of the contemporary world (nuclear war, pollution, etc.).

- Many of the rules are addressed at specific problems of modern Indian society (sectarianism, communalism, specified traditional socially evil customs, social role of vegetarianism, etc.)

- The scheme is casuistic and indicative: ‘class-rules’ only refer to men belonging to 7 male occupational/role categories: students, teachers, businessmen, officials/employers, workers, peasants.

- Class-rules are easier to observe than 11 general aṇuvratas because they are more specific.

- Specified contexts of action are selective and indicative: elections, exams, etc.

- More general rules are specified either by similar rules or by sub-rules [since exhaustive description of a particular situation from the point of view of intuitive prima facie principles is impossible: a two-level ethics results]

- In later versions specifications were removed to generalise some rules

- The removal of specifications render some rules inapplicable without further interpretation by an accepted authority or logical argument (evil social customs).

- •The rules are negatively formulated of the form ‘I will not _’

Note:

Not all universalistic moral rules have to appeal to common interest. Negative principles, characteristic of consequentialist schemes of universal morality such as these, can be universalised by single or double-negation (e.g.: instead of the positive rule ‘do cooperate’ Jaina rules implicitly prescribe: ‘do not not cooperate’).

(See speaker’s: Power and Insight in Jaina Discourse, in Balcerowicz, Logic and Belief in Indian Philosophy, 2010)

- The international code of conduct presupposes

- (a) the possibility of passing moral judgments on social collectives;

- (b) the rejection of the doctrine of human rights (non-imposition of an ideology, non-interference).

Unique Universal Rules of the Aṇuvrata-Scheme

- Disarmament

- Non-Pollution of the Environment

(Cf. UN Declaration of Human Rights).

Observation on the Use of the Rules as Vows

- Many classical ethical/moral schemes were intended as an ‘art of life’:

- addressed to an individual (only secondarily/indirectly social ethics)

- recommendation without obligation

- addressed to an individual (only secondarily/indirectly social ethics)

- Terāpanth insistence on self-obligation turns moral rules into quasi-legal norms (with external and internal sanctions attached: exclusion, loss of face, bad conscience)

Blind Spots

- What are ‘good- / bad actions’?

We are not told why certain recommended forms of self-obligation are intrinsically good. This is assumed to be self-evident or accepted on the basis of authority rather than insight.

- Actual function of the rules?

Open Question

How do the anuvratis who have taken the vows relate to them in day-to-day conduct?

Impact

In the first 10 years, 1949-1959, more than 100.000 have adopted the aṇuvratas.In 1971 members “limited mainly to the members of the Terapanth sub-sect” (Guseva)

Important Pedagogical Effect

“On the one hand this involved an activism with little effect which has been compared with an ‘internationalist western-style peace-movement’. On the other hand […] his statements highlighted several contemporary problems in India which have not always been focussed on with the same clarity” (K. Bruhn)

Concluding Observations

- The normative content of the generally acceptable aṇuvratas overlaps with other lists of norms in text-based religions (with significant variations).

- Hence the aṇuvrat movement could link up with the ongoing discourse on global ethics (Küng etc.) but needs to more clearly differentiate shared themes and particular moral rules specific to Indian / Jain culture and religion.

- The fundamental question is how do the moral rules of the aṇuvrat movement relate to other moral systems? Does anekāntavāda alone suffice?

- The ways in which individual morality and social morality can be integrated or combined without losing coherence of the moral system should be explored further.

Example: Mutual Implication of Ethics of Non-Violence and Discourse-Ethics?

“Jain authors have also formulated a principles of discourse intended to transcend cultural boundaries. These principles can, however, only claim universality to the extent that they fulfil the condition of universal acceptability. Yet, this criterion is not foregrounded in Jain texts.

A rational defence of the universality of Jain ethics will need to reconstruct the presuppositions of the egological Jain ethical perspective from the point of view of general interest. Conversely, discourse ethics rooted in formal pragmatics has only weak regulative force and needs to be supplemented by obligatory norms of action”

(Speaker’s ‘Power and insight’)

Attempted Answer to the Initial

Question:

Why do the 11 ‘universal’ aṇuvratas have not much more impact than the 5 ‘specifically’ Jaina aṇuvratas?

Answer:

Even well-meaning human beings shy away from the demanding legal implications of vow-taking and prefer to use aṇuvratas merely as cognitive devices for sensing moral problems and as maxims to generally morally orientate their actions.

Global Impact of Propagating the Aṇuvratas

- It is unlikely that in India or globally many people will (a) commit to the aṇuvratas and (b) observe them to the letter.

- Only influence on state legislation may have effects on behaviours.

However, the propagation of these rules can still fulfil important cognitive and pedagogical functions (changing attitudes).

What can be done (by Jains)?

- Raising awareness of problems and potential solutions through educations.

Use own expertise in an exemplary way.

Dr. Peter Flügel

Dr. Peter Flügel