Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

There are two principal ways in which the two main objects of worship in the Jaina tradition, the liberated Jinas and mendicants reborn in heaven, are materially represented: statues, bimbas, pratimās or mūrtis, and footprint-images, caraṇa-pādukās. Numerous publications have been devoted to the study of Jaina portrait statues and temples. However, the significance of footprint images and other features of aniconic Jaina iconography in contemporary Jainism has not been seriously investigated.[1] U.P. Shah (1955), in his classic work Studies in Jaina Art does not even mention caraṇa-pādukās in the context of his examination of aniconic symbols in Jainism, nor does K. Bruhn (1994) in his article "Jaina, Iconografia".[2]

In this brief report I will review the development of aniconic iconography in the originally anti-iconic or protestant Śvetāmbara Jaina movements that emerged from the 15th century onwards: the Loṅkāgaccha, Sthānakavāsī and Terāpanth Śvetāmbara traditions. While the role of aniconic representations in the early history of Jaina religious art remains uncharted territory, and probably will continue to be, the re-emergence of selected forms of image-worship in the aniconic Jaina traditions can be reconstructed. There is no doubt about the explicit prohibition of mūrtipūjā, image -or idol- worship, in all three protestant Jaina traditions.[3] However, only few sub-sects of the Sthānakavāsī tradition remain anti-iconic in their practice to this day. The surviving segments of the Loṅkā tradition, now almost extinct, the Terāpanth, and many Sthānakavāsī traditions re-introduced forms of aniconic iconography such as stūpas, footprint images, empty thrones or sacred texts into the religious cult, which resembles the repertoire of early Jaina and Buddhist aniconic art. Sthānakavāsī mendicants, such as Ācārya Vijayānandasūri (1837-1897), who reverted to full iconicism were absorbed into the Mūrtipūjaka tradition.

In the history of the protestant Jaina traditions a development from charismatic to routinised forms of religion is noticeable. It is characterised by a progressive replacement of a radical anti-iconic though never iconoclastic orientation by a doctrinally ambiguous aniconic cult with focus on non-anthropomorphic ritual objects. Broadly three phases can be distinguished: (1) The dominance of anti-iconic movements between the 15th to 18th centuries; (2) the consolidation of a physical infrastructure of upāśrayas or sthānakas and isolated funerary monuments in the late 18th and 19th centuries; and (3) the full development of sectarian networks of sacred places and of an aniconic Jaina iconography, including the internet, during the revival of Jainism in the 20th and early 21st centuries. The following observations focus on the unprecedented construction of tīrthas, places of pilgrimage, in contemporary aniconic Jaina traditions.

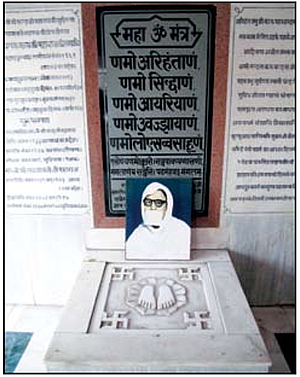

Fig 1 Samādhi Sthal of Tapasvī Sudarśan Muni (1905-1997) and other "Great Gurus" in Ambālā

Burial ad sanctos

A most remarkable development of the last hundred years, not yet recorded in the literature, is the emergence of the phenomenon of the necropolis in the aniconic Jaina traditions, which in certain respects serves as a functional equivalent of the temple city in the Mūrtipūjaka and Digambara traditions, though on a smaller scale. For aniconic Jaina traditions, which by doctrine are not permitted to worship images and to build temples, the mendicants are the only universally acceptable symbols of the Jaina ideals and the focus of religious life. It is not surprising, therefore, that in those aniconic traditions that permitted the erection of samādhis for renowned mendicants sacred sites with multiple funeral monuments developed. Two contemporary examples will suffice to demonstrate how the Jaina cult of the stūpa[4] can become the seed of an aniconic cult of the tīrtha.[5]

The Mahān Gurūo Jain Samādhi Sthal next to the Mahākālī temple in Ambālā features no less than twentyfive samādhis for Sthānakavāsī mendicants of which at least ten are dedicated to sādhvīs (some are unmarked). The suspicion that most of the samādhis are relic stūpas is supported by a plaque which records that the cost of the relic vessel, kalaśa, and the dome, samādhi guṃbad, was paid for by an Osvāl from Ludhiyānā in memory of the virtues, puṇya smṛti, of his deceased wife. This is also common knowledge and orally confirmed by local Jains. The samādhis are tightly packed together, forming a melange of different architectural styles. Four architectural types, reflecting developmental stages, can be distinguished. Twelve smaller solid or hollowed out shrines with niches for oil lamps or offerings, some of them with domed chatrīs, all painted in pink and red, form a stylistic ensemble. According to inscriptions, most of them were constructed in the 1960s and 1970s. The two oldest and most important shrines, of Tapasvī Lālcand, a native of Ambālā, a poor shoemaker from a low caste who became a Sthānakavāsī monk under Muni Uttamcand of an unknown Sthānakavāsī lineage and died in 1843 through the religious rite of voluntary self-starvation, santhārā, and of "Pañjāb Kesarī" Ācārya Kāṃśīrām (1884-1945), one of the most important leaders of the Pañjāb Lavjī Ṛṣi Sampradāya, were renovated in the same modern style in which the funerary monument of Kāṃśīrām's monastic great-grandson disciple, prapautra, Tapasvī Sudarśan Muni (1905-1997) was constructed. (Fig.1) These modern buildings are not solid structures but feature interior shrines with caraṇa-pādukās; in the case of Lālcand a two-storey marble-clad building with spaces for circumambulation of the footprint-image on the upper floor and of prints with detailed instructions on the mode of worship and its "miraculous" benefits on the ground floor. The perceived importance of the deceased is reflected in the relative size of the stūpa. Some older unmarked smaller shrines, painted in white, the third type, were integrated in the shrine of Kāṃśīrām with a new common roof. The three most recent relic shrines, for Tapasvinī Sādhvī Svarṇa Kāṃtā (1929-2001) and two of her associate nuns, are marked by small interconnected platforms, cābutarās, made of shiny marble and attached posters with their photos and biographical data. The combined shrine is covered with a roof made of corrugated iron.

Key to the site are the enduring belief in the miracle working power of Muni Lālcand and of his remains, and the connection with the line of the Pañjāb Lavjī Ṛṣi Sampradāya of Ācārya Kāṃśīrām and his disciples, for whom the Hariyāṇā town of Ambālā, the "Gate to the Pañjāb" with its strategically important upāśraya, became a preferred place for performing the Jaina rite of death through self-starvation, known as sallekhanā or santhārā. Many mendicants of the Pañjāb Lavjī Ṛṣi tradition came to spend their old age in Ambāla in the auspicious presence of Lālcand in order to benefit from his "good vibrations", as the present writer was told, that is, to derive inspirational strength for the wilful performance of a good death, paṇḍita- or samādhi maraṇa. Though cremations are now performed outside the sprawling city, the bone relics of the mendicants are buried ad sanctos next to Lālcand. In this way, a veritable Jaina necropolis emerged over the last century. It is a significant development in the Jaina tradition, nowhere more evident than at this site in Ambālā, that an increasing number of sādhvīs are honoured with funerary monuments, reflecting changing social values.

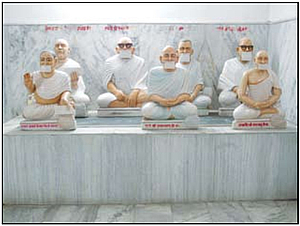

Fig 2 Footprint image of Sādhvī Campakmālā (1904- 1995) with Namaskāra Mantra and photo at the Samādhī Bhavan site in Lohā Maṇḍī

The second example is a site known as Samādhi Bhavan, located at Pacakuriyāṃ Mārg in Lohā Maṇḍī, a small town which is now part of Āgrā. The site is owned by the local Jaina Agravāl organisation, which from the eighteenth century onwards was closely associated with the Sthānakavāsī Manohardās-Tradition, and still serves as a cremation ground for both laity and mendicants. Laity is cremated in a large dugout called svargadhām, heavenly paradise, that is fortified with bricks, and their remains are discarded in the Yamunā River, while mendicants are incinerated on a permanent raised platform constructed on the lawn in the small park adjacent to the main cremation ground. Their remains are entombed on site. Seventeen samādhis are currently identifiable, many of them unmarked. At least two are dedicated to named nuns Sādhvī Campakmālā (1904-1995) (Fig. 2) and Sādhvī Vuddhimatī (died 1997). The name of the site is derived from the 1947 renovated shrine of the principal local saint Muni Ratnacandra or Ratancand (1793-1864), a well-known scholar born in a Rājpūt family near Jaipur who held debates with European Jesuits and members of other religions. He belonged to the Nūṇakaraṇ line of the Manohardās Sampradāy.Since the male line of this tradition, which for a while was well integrated into the Śramaṇasaṅgha, has now died out, the necropolis is an enduring monument to its memory (even if some of the few unmarked monuments may have been built for mendicants of other Sthānakavāsī lineages). All samādhis feature caraṇa-pādukās. The recently renovated samādhis additionally display portrait photographs and supplementary texts and/or colourful reliefs which narrate the life story of the saints. The samādhis, renowned for their wish-fulfilling qualities, are venerated daily by individual members of the local Sthānakavāsī community. However, since the funerary park is distant from the main Bāzār area where many Jaina Agravāls still live, a small commemorative shrine, a glass cabinet containing a printed reproduction of a painting of Ratancand and a rajoharaṇa was created in the main sthānak of Lohā Maṇḍī. The colourfully painted assembly hall of the sthānaka features an empty throne, gaddī, made of marble and an imposing Namaskāra Mantra relief as the main aniconic objects of veneration. This seat is not a personalised "relic of use", like the surviving gaddīs of the Loṅkāgaccha yati Ācārya Kalyāṇacandra (1833- 1887) or of famed Sthānakavāsī ācāryas in Gujarāt, but a generalised symbolic object, explicitly dedicated to the five Jaina parameṣṭīs.

Like in Ambālā, in Lohā Maṇḍī the development of the necropolis as a sacred site is historically linked to the attempt of a locally dominant monastic sub-lineage to establish durable institutional roots in a dynamic sectarian milieu. A motivating factor is the belief in the continuing powers of a deceased saint and the ensuing practice of burial ad sanctos. While avoiding outright idol-worship, two-dimensional iconic images and three-dimensional aniconic images are systematically used for this purpose. Most significant are the footprint-images which only mark cremation or burial sites in the aniconic traditions. They are rarely openly displayed, but housed in shrines of different shapes and sizes - sometimes older structures being wrapped in layers of later, grander structures through successive renovations. The shrines are generally worshipped individually once a day through informal rituals involving touch, bowing and silent prayers or meditation. Occasionally, worship performed both for soteriological and for instrumental purposes or simply out of habit- involves the application of flowers, but despite many parallels, there is never an elaborate pūjā ritual as at the dādābāṛīs of the Kharatara Gaccha tradition studied by J. Laidlaw (1985: 60f.) and L. A. Babb (1996: 127).

The structural relationship between sthānaka and samādhi sthal in the two examples selected from the great variety of aniconic Jaina traditions resembles the relationship between upāśraya and mandira in the idolworshipping Jaina traditions. But in contrast to the imageworshipping traditions, in the aniconic Jaina traditions the main symbolic representations of the Jaina ideals remain the living mendicants rather than anthropomorphic statues of the Jinas (photos or drawings of Jina statues are widely used by followers of the aniconic traditions but peripheral to their religious culture). A problem for the cult of the samādhi and of the multi-shrined necropolis is that it invokes primarily the example, values and powers of a particular deceased mendicant and of his or her lineage or monastic order, not of the Jaina tradition in general. This limits the potential for symbolic universalisation within the aniconic traditions and propels them back toward either idol-worship or imageless meditation or both.

Pilgrimage Places

One of several new ecumenical shrines intended to serve as a common reference point for all branches of the Sthānakavāsī and Mūrtipūjaka Śvetāmbara traditions in the Pañjāb, which seems to underscore these conclusions, is the Ādiśvara Dhām that is currently under construction in the village of Kuppakalāṃ next to the Ludhiyānā Māler Koṭlā highway. It was inspired by the late Vimalmuni (1924-2009), a politically influential modern monk of the Sthānakavāsī Pañjāb Lavjī Ṛṣi tradition, who after leaving the Sthānakavāsī Śramaṇasaṅgha received an honorary ācārya title from Upādhyāya Amarmuni at Vīrāyatan in 1990. The unique design of the religious site was agreed in 1992 with Ācārya Vijaya Nityānanda of the Mūrtipūjaka Tapā Gaccha Vallabha Samudāya II and Ācārya Dr Śivmuni of the Śramaṇasaṅgha, the leaders of the two main rival Jaina traditions in the Pañjāb, who both supported the project. The main shrine combines a traditional Ādiśvara temple in the Mūrtipūjaka style on the first floor of the tower of the main shrine, prāsāda, with a large Sthānakavāsī style assembly cum meditation hall (which is usually situated in a sthānaka). The first floor of the hall features a "mūrti gallery" which also holds an image of the tīrthaṅkara Sīmandhara Svāmī "currently living" in Mahāvideha, and a plate with the Trimantra of the Akram Vijñān Mārg.

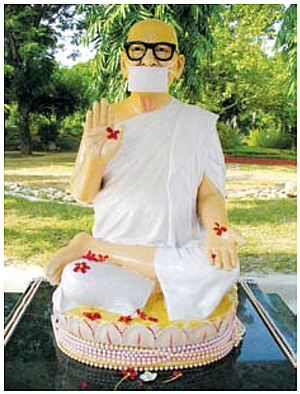

Fig 3 Portrait statues of renowned Pañjābi Sthānakavāsī monks and of Ācārya Vijayānandasūri inside the Ādiśvara Dhām in Kuppakalāṃ

The design of the shrine is quite unusual. Though based on classical paradigms in the Śilpaśāstras, in this case the Śilpa Ratnākara by Nardā Śaṅkara, creative modifications were introduced. Vimalmuni insisted on a disproportionately large temple hall, maṇḍapa, which dominates the tower, śikhara, housing the main shrine. The allocation of the garbhagṛha with the Ādiśvara image to the first floor further changed the symmetries of the classical paradigm. Yet, the key innovation is the construction of two additional underground levels not found in any other shrine. Located below the central pravacana hall is a large meditation hall oriented toward a covered aperture at the centre. A barely visible flight of stairs, locked with iron gates, leads to a second underground level, the so-called guru mandira. The visitor arrives first in a square antechamber, facing two rows of quasi naturalistic portrait statues of six famous Pañjābī monks of the last two centuries, four of the Sthānakavāsī Lavjī Ṛṣi Sampradāya, one of the Sthānakavāsī Nāthurām Jīvrāj Sampradāya, and one of the ex-Sthānakavāsī Mūrtipūjaka ācārya Vijayānandasūri. (Fig 3) An adjacent platform features portrait statues of three renowned sādhvīs of the Pañjāb Lavjī Ṛṣi tradition, amongst them Sādhvī Svarṇa Kāṃtā.From the antechamber, a meandering passage leads to the central shrine, a medium-sized spherical room located right underneath the central point of the meditation hall above to which it is connected with an oblique round opening in the ceiling. In a series of niches along the wall from left to right eleven portrait statues of Sthānakavāsī monks are displayed. The first of the five ācāryas of the Pañjāb Lavjī Ṛṣi Sampradāya are followed by the three deceased Śramaṇsaṅgha ācāryas, including two non-Pañjābīs, and finally three further renowned Pañjābī Sthānakavāsī monks. On the marble pedestal at the centre of the room, containing a collection box, are portrait statues of Vimalmuni's three immediate predecessors presented underneath the opening towards the meditation hall above.The two underground chambers housing this unique ensemble of statues are constructed in such as way as to amplify sounds in order to invite meditative humming in front of the statues. The sound travels through the opening in the ceiling from the bedrock of the shrine upwards to the larger meditation hall. Pūjā is not to be performed.

This so-called guru mandira was inaugurated on 18 May 2005 by Ācārya Dr Śivmuni and Ācārya Vimalmuni. Next to the Ādiśvara Dhām are four other buildings: two administrative blocks, one vast upāśraya which will serve as a "retirement home" for old nuns, and a Dhyāna Sādhanā Sādhu-Sādhvī Sevā Kendra, constructed on request of Ācārya Dr Śivmuni for the practice of meditation as outlined in his books. Plans for a samādhi for the late Vimalmuni await approval from Ācārya Dr Śivmuni.

Ecumenical shrines such as this were first devised by the Jaina Diaspora (which also contributes funding for the Ādiśvara Dhām). Yet, few iconographic innovations were introduced by NRIs. Already half a century ago, if not earlier, it became customary in most aniconic traditions in India to display photographs of prominent monks and nuns in upāśrayas, samādhis and in the homes of disciples for commemoration if not for worship. Often photographs of deceased saints are displayed in conjunction with a two or three-dimensional aniconic cult object, such as an empty or occupied "lion throne" or siṃhāsana.[6] The ensuing controversy over the religious status of twodimensional representations such as photographs, line drawings and reliefs still divides the aniconic Jaina traditions. Yet, three-dimensional statues such as those displayed in the subterranean vaults of the Ādiśvara Dhām presenting recently deceased monks and nuns as objects of meditative worship were previously only produced by the Mūrtipūjaka and Digambara traditions.[7] Despite protests, in the last decade portrait statues were set up of the Sthānakavāsī Upādhyāya Amarmuni (1903-1992) at Vīrāyatan in Rājagṛha (Fig 4) and of the Terāpanth Ācārya Tulsī (1914-1997) in Bikaner (in a hospital) and in a commemorative shrine at New Delhi. The three portrait statues of Sthānakavāsī nuns in Kuppakalāṃ may be the first stone images of female mendicants in the aniconic traditions. Physical worship is prevented in all cases across sects by either encasing the images with glass covers or making access as unattractive as possible. In reply to the question of the legitimacy of worshipping photographs, citra, and other physical representations of Sthānakavāsī mendicants, Jñānmuni (1958/1985 II: 366f.), a leading intellectual of the Śramaṇasaṅgha, in his book Hamāre Samādhān, Our Solution, stated the following view. From the historical perspective, aitihāsik dṛṣṭi, such images are of great benefit, baṛe lābh. But venerating, vandana, and worshipping, pūjā, is not right. If this is not done and pictures are used only for spreading information then even from a scriptural point of view, saiddhāntik dṛṣṭi, there is no fault: "The Sthānakavāsī tradition is not opposed to images but to image-worship"(sthānakavāsī paramparā kā virodh mūrti se nahīṃ hai balki mūrtipūjā se hai) (ib., p. 367).

Fig 4 Portrait statue of Upādhyāya Amarmuni (1903- 1992) at Vīrāyatan in Rājagṛha

Conclusion

Originally, all Loṅkā, Sthānakavāsī and Terāpanth Śvetāmbara traditions explicitly rejected image worship, and many still do. The Jñānagaccha or the Kacch Āṭh Koṭi Nānā Pakṣa and other Sthānakavāsī traditions in Rājasthān and Gujarāt, though reliant on a network of sthānakas, remain orthodox in their rejection of all "lifeless" material representations, including all print publications. I have therefore used the term "idol-worship" advisedly as contextually a more appropriate, albeit old fashioned, translation of mūrtipūjā, given that many originally anti-iconic traditions came to accept and worship certain aniconic images, such as relic shrines, empty thrones or stylised footprints, that is, real or simulated relics of contact, and hence have become, to varying degrees, "image-worshipping" traditions in their need and desire to establish networks of abodes and of sacred sites, whether labelled tīrtha, dhām or aitihāsik sthal, as durable institutional foundations. This is often done in the name of material security in particular for nuns and old mendicants, the stalwarts of the Śvetāmbara Jaina tradition. Without an institutional base supported by devout laity, even the potential alternative to image worship of an aniconic cult of the holy book is difficult to realise. When in 1930, the strategically placed first book publication featuring images of Mahāvīra and Bāhubali wearing Sthānakavāsī mukhavastrikās appeared ("Picture for Information, Not for Veneration"),[8] the resolution for the creation of a nationwide institutional framework for all Sthānakavāsī mendicants taken at the Ajmer Sammelan was only two years away. In one respect the cult of the sacred text is the most significant innovation in the repertoire of aniconic Jaina iconography. In all shrines of the aniconic traditions physical representations of the Namaskāra Mantra are centrally displayed, carved in marble, cast in bronze, painted or printed, on the wall or on a stele. Increasingly popular is the use of the so-called tīrtha kalaśa, which elsewhere is known as maṅgala kalaśa, or auspicious pot. (Fig 5) It is a silver vessel inscribed with the Namaskāra Mantra and sealed with an auspicious silver coconut, representing the fruits of Jaina practice both in the other world and in this world. It is portable, like the Jina statues used for processions, and can be utilised as a tangible cult object in variable contexts. Only in combination with the "Navkār Mantra" relic shrines, footprint images or photographs of individual Jaina saints can gain universal appeal and become potential tīrthas or crossing points over the ocean of suffering.

Fig 5 Tīrtha kalaśa in front of a painting of Ācārya Ātmārāma (1882-1962) in the Ātma Smṛti Kakṣa, Jain Dharmaśālā, in Ludhiyānā

References

Babb, Lawrence A. Absent Lord: Ascetics and Kings in a Jain Ritual Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Bakker, Hans T. "The Footprints of the Lord." Devotion Divine: Bhakti Tradition from the Regions of India. Studies in Honour of Charlotte Vaudeville. Edited by Diana L. Eck & Francoise Mallison, 19-37. Groningen: Egbert Forsten, 1991.

Bruhn, Klaus. "Jaina, Iconografia." Enciclopedia Dell'Arte Antica Classica E Orientale. Secondo Supplemento 1971-1994, Vol. III, 65-73. Roma: Instituto Della Enciclopedia Italiana Fondata Da Giovanni Treccani, 1994.

Flügel, Peter. "The Unknown Loṅkā: Tradition and the Cultural Unconscious." Jaina Studies. Papers of the 12th World Sanskrit Conference Vol. 9. Eds. Colette Caillat & Nalini Balbir, 181-278. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 2008.

Flügel, Peter. "The Jaina Cult of Relic Stūpas." Numen 57, 3 (2010) (in press).

Hegewald, Julia A. B. Jaina Temple Architecture: The Development of a Distinct Language in Space and Ritual. Monographien zur indischen Archäologie, Kunst und Philologie Band 19. Berlin: G.H. Verlag, 2009.

Hegewald, Julia A. B. "Visual and Conceptual Links between Cosmological, Mythological and Ritual Instruments." International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) Vol. 6, No. 1 (2010) 1-19.

Jain, Puruṣottam & Ravindra Jain. Vimala Vyaktitva. n.d. http://www.jainacharya.com/files/pdfs/vimal muni/vimalmuni_biography.pdf

Jñānmuni [Muni Jñān]. Hamāre Samādhān. Vol. I-II. Sampādak: Muni Samadarśī. Karaṛ/Ropaṛ: Śāligrām Jain Prakāśan Samiti, 1958/1985.

Laidlaw, James. "Profit, Salvation and Profitable Saints." Cambridge Anthropology 9, 3 (1985) 50-70.

Śaṅkar Muni. Sacitra Mukh-Vastrikā Nirṇay. Ratlām: Jainoday Pustak Prakāśak Samiti, 1930.

Schopen, Gregory. "Stūpa and Tīrtha: Tibetan Mortuary Practices and an Unrecognized Form of Burial Ad Sanctos at Buddhist Sites in India." The Buddhist Forum 3 (1994) 273-293.

Shah, Umakant Premanand. Studies in Jaina Art. Varanasi: Pārśvanātha Vidyāpīṭha, 1955.

In the Study of Religions the term "icon" refers to an artistic representation of a sacred being, object or event. The term "aniconic" is often used is as a synonym of the words "anti-iconic" and "iconoclastic" which designate the rejection of the creation or veneration of images, and the destruction of images of a sacred being, object or event. In Art History, the word "aniconic" is used in a less loaded way as a symbol that stands for something without resembling it. Because of these ambiguities, the specific attributes of an "aniconic tradition" therefore need to be identified in each case.

Bakker (1991: 23, 28, 30) traced archaeological evidence for (viṣṇu) padas from the first centuries CE.

Dr. Peter Flügel

Dr. Peter Flügel