Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

The British Museum holds at least 125 Jaina objects from India that span almost two thousand years of Jaina history. Stone and metal sculpture is particularly well represented, although a small number of textiles, painted palm-leaf manuscripts and a yantra that dates to 1631 are also included among the collections. The refurbishment of the Sir Joseph Hotung Gallery for China and South Asia, which reopened in November 2017, was a good occasion to reassess the Jaina holdings and to display objects that were previously in the reserve collections. It also provided an excellent opportunity to make the collections better known to colleagues outside the museum and the general public, and to bring Jainism to the attention of the Museum's many visitors. The new layout takes a broadly chronological approach to the different regions in South Asia. Within this scheme, the Jaina objects are displayed in three main sections: Mathurā, Western and Central India, and the Deccan. The Edwardian mahogany display cases that are original to the gallery have been retained and all of the objects, with the exception of very large sculptures, are on display within these cases. What follows is by no means an exhaustive account of the Jaina collections, but an introduction to the material that gives a broad overview. Overall, it is notable that a large proportion of the Jaina sculptures were acquired in India and donated to the Museum by British colonial officials in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Figure 1. āyāgapaṭa (fragment, reverse shown)

Mathura, 1st century CE (front) and 3rd or 4th century CE (reverse)

Sandstone

British Museum Asia 1901,1224.10

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Figure 2. Standing figure of the goddess Sarasvatī

Rajasthan, mid-11th century

White marble

British Museum Asia 1880.349

Mathurā

Like most museums outside India, the British Museum does not have an extensive collection of sculpture from Mathurā. In 1901, Lord George Francis Hamilton, Secretary of State for India (1895-1903), gave eleven objects from Mathurā to the Museum. This donation included all of the Jaina objects from Kankali Tila in Mathurā that the museum now holds. It is not clear how, or from whom, he acquired this material.

The earliest of these objects is a fragment of an āyāgapaṭa ('plaque of veneration'). (Figure 1) The earlier face, dating to the c.1st century CE, has circular bands of floral motifs as well as a small seated Jina flanked by celestial garland bearers. It was re-used in antiquity and the carving on the reverse dates to about the 3rd or 4th century CE. This later side features the lower half of a Jina with hands in dhyānamudrā sitting on a lion throne, and devotional figures standing beneath. Railing pillars are also displayed in this section but their religious context is unclear.

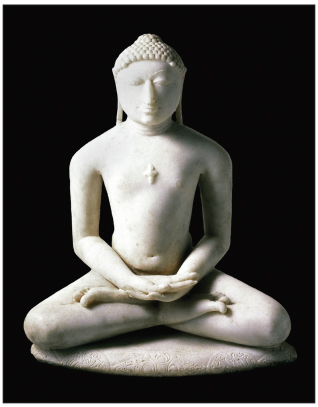

Figure 3. Seated figure of a tīrthaṅkara

Gujarat, mid-12th century

White marble

British Museum Asia 1915,0515.1

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Western and Central India

The museum holds a range of Jaina objects from Western and Central India, and a selection of these are now on display in the Hotung Gallery. These include white marble sculptures of a mid-11th-century representation of Sarasvatī from Rajasthan (Figure 2), and a mid-12thcentury tīrthaṅkara from Gujarat. (Figure 3) The latter was donated by Sir Alfred Comyn Lyall (1835-1911), a prominent British colonial official in India, and the first Chancellor of Allahabad University.

Three copper alloy sculptures of tīrthaṅkaras are also on display. One, from Gujarat, is among the earliest in the museum's collections and dates to the 7th or 8th century. Another example depicts Saṃbhavanātha, and the inscription on the back reveals that in 1454 it was dedicated by members of the Jaina community from the town of Srimala (now 'Bhinmal') in Rajasthan.

The central object in this section, however, is the important sculpture of Ambikā from Dhār.[1] The inscription written in Sanskrit in the Nāgarī script records that one Maṇathala carved this sculpture and Śivadeva inscribed it in 1034 or 1035. Vararuci, a member of the court of King Bhoja (reigned c.1000-1055) commissioned this and other sculptures. This piece was acquired in India by Maj.-Gen. William Kincaid (1831-1909) and donated to the museum where it was registered in 1909.

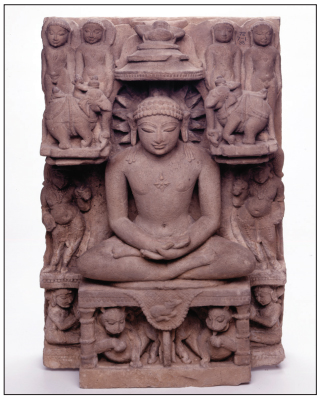

Among the exceptional collections of Maj.-Gen. Charles 'Hindoo' Stuart (1757/58-1828) that were subsequently acquired at auction by John Bridge (17551834) and later donated to the museum, is an 11thcentury sandstone sculpture depicting Ṛṣabhanātha. (Figure 4) This object seems to be mentioned in Stuart's will where the provenance is given only as 'Bundle Cd' ('Bundelkhand'). It is possible that Stuart acquired it in Khajuraho, but this is by no means certain.

Deccan

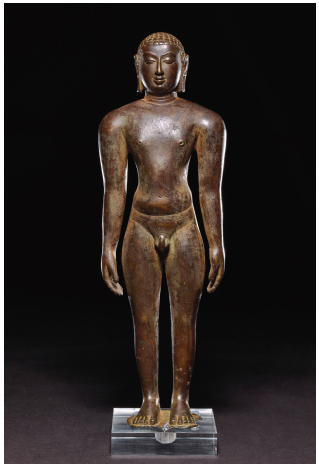

As with the collections from Western India, the museum holds a range of stone and metal Jaina sculpture from the Deccan. A selection of the copper alloy sculptures is on display. Most of this material dates to the 10th11th centuries and include images of Pārśvanātha, a vidyādevī and a yakṣa and yakṣī. An 11th-12th-century tīrthaṅkara figure standing 44 cm high was donated by Sir Walter Elliot (1803-1887), who excavated the stūpa at Amaravati. (Figure 5)

Figure 4. Seated figure of Ṛṣabhanātha

Probably Bundelkhand. Dated to the 11th century

Sandstone

British Museum Asia 1872,0701.98

© The Trustees of the British Museum

A rare stone container sits alongside this figure. (Figure 6) The object may have functioned as a portable shrine, or perhaps a container for ritual utensils such as a māla. Three tīrthaṅkaras are carved on the lid of this unusual Jaina shrine, and Bāhubalī is depicted inside as the main icon for worship. This devotional object dates to the 16th or 17th century, and may be from Karnataka or southern Maharashtra. It was acquired by the Museum in 1888, but the precise details, including the name of the donor, are unclear.[2]

Four stone sculptures are displayed in this section, including an 11th-12th-century figure of Padmāvatī with a serpent canopy covering her head and a small seated figure of Pārśvanātha above it. A highly polished 13thcentury Hoysala sculpture of a standing tīrthaṅkara is placed alongside a later sculpture of Bāhubalī, possibly from Rajasthan, and a Jaina yantra that dates to 1631. Finally, there is a standing figure of a tīrthaṅkara (Figure 7) that was originally part of the collection of Sir Stamford Raffles (1781-1826), Lieutenant-Governor of Java and founder of Singapore. It was among the Raffles material that was donated to the museum by his nephew, Rev. W. C. Raffles Flint in 1859.[3]

Figure 5. Standing figure of a tīrthaṅkara

Deccan, 11th-12th century

Bronze

British Museum Asia 1882,1010.26

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Figure 6. Portable shrine or container for ritual objects (2 views:

Above: exterior; Below: interior)

Stone

Southern Maharashtra or Karnataka, 16th-17th century

British Museum Asia 1888,0515.5

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The central object in this overall section is a striking dark grey schist sculpture of Pārśvanātha that is almost a metre tall. The tīrthaṅkara is flanked by fly-whisk bearers, and Dharaṇendra and Padmāvatī sit by his knees. The sculpture was originally part of the East India Company's Indian Museum on Leadenhall Street, City of London. Once this museum closed in 1879, it was transferred to the British Museum.

Unfortunately, a number of constraints had an influence on the objects selected for display in the gallery. This was due mainly to the display space available in the Edwardian cases, the size of the objects, and the lightsensitivity of the material from which some of the objects were made. Some of the Jaina material that is not displayed in the Hotung Gallery can be seen on the Museum's Collection Online (www.britishmuseum.org/ research/collection_online/search.aspx). My aim here was to give a representative overview of the temporal and geographical breadth of the important Jaina material that is held at the British Museum, and a taste of what is on display in the refurbished gallery. I hope you are able to come and visit the new displays, and enjoy them.

Figure 7. Standing figure of a tīrthaṅkara (possibly Munisuvrata)

Deccan, 12th-14th century

Stone

British Museum Asia 1859,1228.172

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Dr Sushma Jansari

Curator Asian Ethnographic and South Asia Collections

See: Willis, Michael, 'New Discoveries from Old Finds,' Jaina Studies: SOAS Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies, 6, (March 2011), 28-30.

Exemplifying scholarly collaboration, colleagues from institutions in the UK, India and the USA kindly shared their knowledge and thoughts about this shrine.

Alongside his better-known Javanese collections, Raffles also had a small but superb collection of material from India that is now held at the British Museum, including 18th-century Thanjavur paintings. When I was looking through his drawings, I came across one that depicted the interior of a Jaina temple. The drawing dates to about 1783 and was presented by Thomas Law to C. Wilkins. These individuals are presumably the British East India Company employees Thomas Law (1756-1834), a judge who lived and worked in Bihar, and Charles Wilkins (1749-1836), the well-known linguist. During this period, colonial officials knew little of the Jaina religion. This lack of knowledge about Jainism is evident in the title Law gives to the drawing: 'Inside the Temple of Boodha [Buddha] at Gaya'. This is despite the obviously Jain iconography Pārśvanātha is flanked by numerous figures of other tīrthaṅkaras in the garbha-gṛha of a Jain temple. How this drawing came to be in Raffles' possession is not clear. This drawing will not be on display in the gallery, but it can be seen on the Museum's Collection Online.

Sushma Jansari

Sushma Jansari