Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

District Chakwal has long been known for its Buddhist, Hindu and Jain archaeological heritage. A previously unreported caraṇa-pādukā stone block has recently been discovered near the peak of Chel-Abdal in Basharat, District Chakwal, Pakistan. This current discovery is unique as it is the first time in the Chakwal district that any Jaina footprints have been discovered.

Chel-Abdal near Bisharat (now spelled as Basharat) (N 32.75987 E 73.06309) is the highest point in the District Chakwal (3500 ft. above sea level). This ridge along the valley of Bisharat is visible from Ara-Bisharat. Facing west to east this ridge is about 8 km in length and is located between the villages Kotli and Ara. On top of the ridge there is a shrine called Chel-Abdal, which means "Forty Saints."[1] From the peak of Chehl-Abdal one can see the Margla hills to the north; to the south flows the Jhelum river; and to the east and west on adjoining hills is situated a dense rain forest.

Sir Marc Auriel Stein (1862-1943) visited Salt Range in 1889, 1901 and 1930. On 2 December 1930, on his way from Ara through Pathak (Modern Pir Phattak) and Umbrila, Stein arrived at the "large village of Bisharat," but he did not notice Chel-Abdal, nor did he notice any archaeological sites in the surroundings of Bisharat.

Stein identified the ancient capital of Simhapura at Dulmial five km north-west of Ketas. Five kilometers downwards from Ketas along the stream he discovered the ruins of "Gandhala Murti," a Jain temple located at Murti (Jhelam) in the Gandhala valley (Stein 1937:57).[2] Stein concluded that Gandhala Murti perfectly matched the description written in the 7th century by the Chinese scholar and pilgrim Heun Tsiang for the place near Simhapura where Mahāvīra was thought to have arrived at the knowledge of principles which he sought, and where he first preached the law. According to Stein:

At Murti, I discovered Hsuan Tsang's site of the white-robed Heretics & located the ancient capital of Simhapura he had visited near the present pilgrimage place of Ketas (Mirsky 1977: 472).

It is worth quoting here part of what Heun Tsiang actually wrote about the monks of this temple:

They have a little twist of hair on their heads, and they go naked. Moreover, what clothes they chance to wear are white. (Heun Tsiang 1884: 145).

This either indicates that the distinction between the two Jaina sects in the region was nominal at time when Heun Tsiang visited Chakwal, or that he was confused (as the translator Samuel Beal suspected). The naked male and dressed or partially dressed female sculptures from the temple in Murti give some credence to Heun Tsiang's observations.[3]

Figure 1. Caraṇa-pādukā stone block discovered near the peak of Chel-Abdal in Basharat. (Photo Courtesy of Mr Raza Ullah Khan, Official Photographer of Nazarat Taleem School Systems, Pakistan.)

Stein removed 30 camel-loads of sculptures and architectural ornaments from the site and shifted them to the Lahore Museum (Gazetteer. Jhelum 1904: 45). He found them similar to the Jain sculptures at Ellura and Ankai. Amongst the red sandstone sculptures from Murti were sculptures of naked males sitting and holding garlands (Gazetteer. Jhelum 1904: 45). This particular feature reminds us of Digambaras. He noted the local tradition that the Murti temple was built by a Jain minister (Stein 1937: 1-57).[4] Between Murti and Katas is the pond where Śiva supposedly wept on the death of his wife. Katas was famous for Vyāsa the Hindu muni. On the road to Bisharat there is Pir Phatakk (Stein's Raja Pathak).

Discovery

Around 1996 I visited the peak shrine of Chel-Abdal with Mr. Riaz Ahmad Malik from Dulmial, an expert on the history of the region and the author of several books. Local Patwari told us the ziarat was built upon the ruins of an ancient temple.[5] Around 1971 Jain sculptures were discovered here which were sent to the Lahore Museum. Recently, after all these years, Mr Malik brought to my notice the discovery of a red sandstone block with feet carved on one side. According to Mr. Malik, the red sandstone block was brought to him by a contractor who was digging a mine in the area near the site of the temple. In his own words: "The red sandstone slab with foot prints on it was found at Chel-Abdal, about six months ago, about 100 yards below the peak of Chel-Abdal." He brought the slab for a brief period of time to our workplace in Rabwah, a town in District Chiniot Punjab. I managed to make a plaster of Paris mold of the feet area, photographed it, and took measurements. (Figure 1)

Description and Stylistic Analysis

The red sandstone block is of a lighter colour and quarried no doubt from the surroundings. A very thin white layer is visible on the surface. The slab is broken around the corners. Most of the toes are also slightly damaged.

The block with carved feet in high relief most probably represents the Jain tradition. They do not appear to be buddhapada, first introduced in the 2nd century BCE (Quagliotti 1998:169-171), or viṣṇupada, first introduced in the 1st century CE (Cicuzza 2011:19). Both buddhapada and viṣṇupada were represented in a very abstract way and adorned with different religious symbols. In the case of the caraṇa-padukās on the stone block, no symbol of any type is visible, which shows that it is of a considerably earlier date. Moreover Jain caraṇa-pādukās do not represent a sole footprint or foot, but a pair. Also, while the other two styles mentioned above are adorned with cakras and other religious motifs, Jain caraṇa-pādukās were mostly carved without any symbols. A peculiar feature of these caraṇa-pādukās is the natural rounded shape of the feet with toes carved in an almost natural shape. The feet are carved in a quite naturalistic way and the artist tried to depict minor details like the gaps between the toes, and also beautifully carved nails.

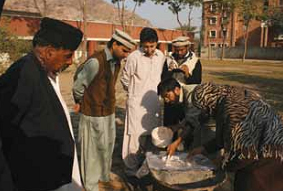

Figure 2. Making a cast of the caraṇa-pādukā on the lawn of the Research Cell. (Right to left) Riaz Malik, Saher Naeem (Archaeologist, Nazarat Taleem School Systems), Muzaffar Ahmad and his students, Naseem Fazeel, Abdul Rahman, and Nemat Ullah.

Measurements

| Size of Right Foot: | Size of Toes (right foot): |

| Length= 20cm | Width of big toe = 1.5cm |

| Width (toe) = 8.4cm | Width of first toe = 1.1 cm |

| Width (ball) = 5.9cm | Width of second toe = 1cm |

| Width (instep) = 5.8 cm | Width of third toe = 0.6 cm |

| Width (heel) = 4.8cm | Width of little toe = 0.6cm |

| Size of Left foot: | Size of Toes (left foot): |

| Length= 20cm | Width of big toe = 1.6cm |

| Width (toe) = 8.3cm | Width of first toe = 1.3 cm |

| Width (ball) = 6.4cm | Width of second toe = 0.9cm |

| Width (instep) = 6.1cm | Width of third toe = 0.8cm |

| Width (heel) = 6cm | Width of little toe = 0.6cm |

The stone block appears to have been fixed in the floor of a chatra or a temple.

Jain Tradition

In Jainism carving caraṇa-cinha or caraṇa-pādukās on stone is an ancient tradition. Footprints are still carved on stone blocks or slabs and it is safe to assume that at least in an early phase they were carved without any decorative motif or sacred symbol. There is a tradition of placing stone blocks carved with sacred feet at the top of hills, where they are worshipped ceremoniously at least once a year. New footprints of Jain monks and nuns are regularly added to the sacred topography of Jain religious landscape. Caraṇa-pādukās in high relief are one of the oldest and most common emblems worshipped by Jains. They often mark a spot at which a renowned ascetic is believed to have died. They represent the soul's conscious departure from the mortal body through voluntary selfstarvation (Bruhn 1998: 229-232). Presumed nirvāṇa bhūmis, predominantly on mountains, are marked by caraṇas. Flügel (2011:2) notes the difference in style between Śvetāmbara and Digambara caraṇas (and that they are prohibited and non-existent in the samādhi architecture of the Śvetāmbara Terāpanth).

Keeping in mind the material, artistic style and the religious topography of the area, it could be said that these newly discovered footprints are of the Jain tradition. As they are not properly recorded in situ, only a future archaeological study can answer the many remaining questions. In Bisharat the ziarat, or shrine, of Chel-Abdal exists, it must be concluded, on the remains of a temple or chatra with caraṇa-pādukās or footprint-images. Caraṇa-pādukās on a peak represent the place visited by some holy person in Jainism. All this information makes it quite feasible to assume that some holy person/persons travelled through this beautiful valley on their way to Taxila or Kashmir. The Hindu sources, the Chinese travel account and the local traditions are not telling the story of a tomb, but of the visits paid by Śiva, Mahāvīra or the Chel-Abdal on their way, which could be either to Kashmir via Nara or to Taxila via Umbrila. In Bisharat there is a famous proverb relating to the legend of Chel Abdals: Chelan dhote kapre, hik bhora te hik Dang, i.e. "Chels washed their cloths here which comprised of a rough woolen clock and a walking stick."

Muzaffar Ahmad is currently enrolled in an MPhil program, University of Hazara, Department of Archaeology, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. He is also an archaeological consultant with Nazarat Taleem School Systems (http://taleem.saapk.org).

References

Bruhn, Klaus. "The Jaina Art of Gwalior and Deogarth." Jainism a Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence. Ed. Kurt Titze, 101-118. Dehli: Motilal Banarsidas, 1998.

Cicuzza, Claudio. A Mirror Reflecting the Entire World: The Pali Buddhapadamaṅgala or "Auspicious Signs on the Buddha's Feet." Fragile Palm Leaves Foundation, Lumbini. Bangkok: Lumbini International Research Institute, 2011.

Flügel, Peter. "Burial Ad Sanctos at Jaina Sites in India." International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 7,4 (2011) 1-37.

Gazetteer of the Jhelum District. 1907 Lahore: Punjab Government. (Reprint 2004. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publishers.)

Hiuen Tsiang (Hsuan-tsang) Trans: Bead, Samuel. SiYu-ki Buddhist Records of the Western World Volume 1. London: Trübner and Co. 1884.

Mirsky, Jeannette Sir Aural Stein: Archaeological Explorer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 1998.

Quagliotti, Anna Maria. Buddhapadas: An Essay on the Representations of the Footprints of the Buddha with a Descriptive Catalogue of the Indian Specimens from the 2nd Century B.C. to the 4th Century A.D. Kamakura-shi, Japan:Institute of Silk Road Studies, 1998.

Stein, Marc Aural. Archaeological Reconnaissances in North-Eastern India and South-Eastern Iran. London: Macmillan and Co. 1937.

Chel (plural Chelan) is most probably derived from the Sanskrit Chela, but in its current usage local people associate it with forty wandering saints known in Sufi literature as Chehel Abdal (40 great saints), a concept well known in Islamic mysticism, these 40 saints are held to always remain on earth as a link between mankind and divinity.

Archaeological Survey Reports, vol. ii, pp. 88 and 90; A. Cunningham, Ancient Geography of India, pp. 124-8; Vienna Oriental Journal, vol. iv (1890), pp. 80 and 260. Imperial Gazetteer of India. vol. xv. Oxford 1908

Heun Tsiang rightly observed the existence of different religious classes amongst the Jainas. His confusion is, if at all, only related to Mahāvīra, who was not the founder specifically of the Śvetāmbara tradition ('white-clad herectics').

"Here a curious piece of information gathered from Devi Dyal, the aged Brahman Purohita of Chôa Saidan Shah, may find mention. At an inquiry held by me in 1890 among the village elders concerning the materials quarried from Murti, he mentioned having heard from his father that travelling sabhus [sic] had described the ruined temple as having been 'built before the time of Raja Man' by a Jain minister as a place of prayer and meditation for mendicant priests. Is it possible that tenacity of Jaina tradition had retained some faint recollection of the sanctity originally attaching to the spot?" (Stein 1937 Section 1: 57 n. 15).

Muzaffar Ahmad

Muzaffar Ahmad