Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

From August 5 through October 23, 2011, the New Orleans Museum of Art presented The Elegant Image, an exhibition of South Asian bronzes (or, more accurately, copper-alloy sculptures), almost all of which were from the collection of Dr Siddharth K. Bhansali. Nearly one-third of the sculptures on display were Jain. While the significant presence of Jain bronzes in this exhibition reflects the personal history and collecting interest of Dr Bhansali, it also underscores a fact often underemphasized if not even ignored by historians of South Asian bronzes: for two millennia, Jain patrons have played a major role in shaping bronze sculpture in the subcontinent. While the exhibition and accompanying catalogue include many important Hindu, Buddhist (and a few folk) sculptures, in this brief review I focus only on the Jain sculptures.

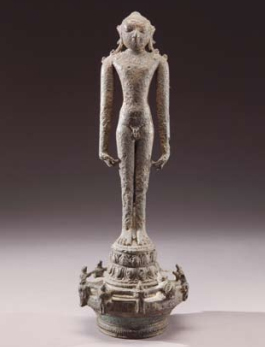

Figure 1. Jina Pārśvanātha Bihar, Kuṣāna period, 2nd-3rd century Copper-alloy, 12.4 cm Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection Image © New Orleans Museum of Art

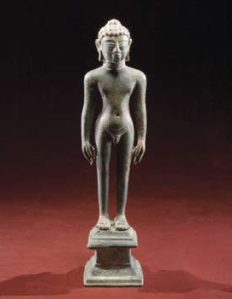

Figure 2. Jina Ṛṣabhanātha in a Maṇḍala Jharkhand, Manbhum, Post-Gupta period, 8th century Copper-alloy, 29.8 cm Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection Image © New Orleans Museum of Art

The two great centers for the development of anthropomorphic sculpture in ancient South Asia were Gandhara and Mathura. The Jains were central participants in the developments at Mathura, but they appear to have been absent from Gandhara. Further, the Mathura tradition appears to have been one of stone sculpture, not metal-casting. The earliest Jain bronzes, therefore, come from northeastern India, in the area that is now Bihar and Jharkhand. The exhibition includes some sculptures that are important as some of the earliest extant Jain bronzes, including a standing Pārśvanātha dated to the 2nd3rd century CE (Figure 1), three standing Jinas dated to the 4th century, a seated Jina dated to the 5th century, a seated Ṛṣabhanātha from c. 500, and two images of the goddess Ambikā, also from c. 500. The earliest of these bears strong similarities to the oft-discussed bronzes of the Chausa hoard, and is further evidence that this was a robust regional tradition from an early date. We do not have a social or sectarian context in which to locate these sculptures, but they clearly indicate that the Jain role in the development of bronze sculpture in Bihar was as important as the Jain role in the development of stone sculpture in Mathura. Slightly later sculptures, such as an 8th-century standing Ṛṣabhanātha from Manbhum (Figure 2), and a 9th-century seated Ṛṣabhanātha from Jharkhand or Bihar, indicate that the Jains continued to have an important presence in this region, the original heartland of the Jains, for many centuries.

Perhaps the best-known regional tradition of Jain bronzes is that from what broadly we can call western India, encompassing the current states of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. One of the outstanding sculptures in the exhibition is a tall (15 ¼ in.) standing sculpture of Mahāvīra as Jīvantasvāmī ("The Lord as Living"), dated to the 5th century. (Figure 3) This sculpture of a crowned, royal figure of Mahāvīra as a prince, before he renounced the world, is understood by Śvetāmbara Jains to be a copy of a sandalwood sculpture carved during Mahāvīra's own lifetime.[1] Two of the most famous of the very few of these sculptures that are extant are from Akota, outside contemporary Baroda, and have been dated to the 5th-7th centuries. The curator of The Elegant Image, Pratapaditya Pal, suggests a slightly earlier date for this sculpture, of the 5th century, on the grounds that this one is slightly simpler in style than the two known Akota sculptures.

Figure 3. Jina Mahāvīra as Jīvantasvāmī Gujarat, Gupta period, 5th century Copper-alloy, 38.7 cm Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection Image © New Orleans Museum of Art

Figure 4. Jina Ṛṣabhanātha Rajasthan or Madhya Pradesh, Gupta period, 5th century Copper-alloy, 23.8 cm Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection Image © New Orleans Museum of Art

Figure 5. 'Five Jina' Image with Ṛṣabhanātha Madhya Pradesh (?), Chandela period, dated VS 1068 (1011 CE) Copper-alloy, 21.3 cm Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection Image © New Orleans Museum of Art

The other ten sculptures from western India are dated from the 5th through 11th centuries. The progress of these sculptures, from a relatively simple 5th-century sculpture with just Ṛṣabhanātha seated on a throne,[2] to a complex sculpture datable to 1011 CE on the basis of its inscription, illustrates well the development of an ever more complex iconography of this regional tradition. (Figures 4 and 5) The 11th-century Digambara Ṛṣabhanātha sculpture, possibly from Madhya Pradesh, includes four standing Jinas that flank the central seated Jina, making it a pañca-tīrthika icon. In addition, it includes a lion-throne, a triple canopy, figures of the nine planets, the attendant yakṣa and yakṣī, fly-whisk bearers, garland bearers, and lustrating elephants, all in a much more elaborately ornamented style. This is a fine representative of the fully developed western Indian style, one that continued for many centuries.[3]

Figure 6. Kāyotsarga Image of a Digambara Jina Andhra Pradesh, Pallava period, 6th-7th century Copper-alloy, 50.8 cm Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection Image © New Orleans Museum of Art

Figure 7. Jina Supārśvanātha Tamil Nadu or Karnataka, Chola period, 12th century Brass (?), 26 cm Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection Image © New Orleans Museum of Art

The Indian bronze sculptural tradition that is perhaps best known outside of India is that of south India, in particular Tamil Nadu, but also Karnataka. The Jains are also well-represented in both these regional traditions (and the catalogue includes several spectacular sculptures that were not in the exhibition, to provide a fuller sense of these styles). There are several sculptures from 6th-7th century Andhra Pradesh, including two standing Jinas that illustrate the temporal and geographic extent of the fuller south Indian style. (Figure 6) Most of the Tamil sculptures in The Elegant Image are Hindu, but the Jains are well represented here as well, as seen in a 12th-century Supārśvanātha. (Figure 7) The only regional tradition in this exhibition in which Jain sculptures are not found is that of Keralaalthough this may represent more what sculptures have emerged onto the global art market than anything else, for there has been a Jain presence in Kerala for many centuries.

The permanent record of this fine collection is the comprehensive catalogue by Pratapaditya Pal (who has also advised Dr Bhansali over the years in his purchases, so this collection bears the stamp of his curatorial sensibilities). It is profusely illustrated with excellent color photographs, and will remain an essential source for the study of South Asian (and therefore Jain) art. The framing essays and detailed catalogue descriptions are very much in the style of this well-known and highly respected scholar of South Asian art. He expresses his approach to the subject explicitly when he writes in the preface, "This is primarily an art-historical publication where matters of style, iconography, chronology, etc., are given precedence. While I realize that it is fashionable today to study art as 'material culture' or as an object of 'political football', I have indulged in expressing my personal aesthetic response, even though the principal motivation behind these works was piety rather than beauty."[4] While one may not always agree with the curator's methodological and theoretical preferences, anyone who saw the exhibition in New Orleans, or peruses the catalogue, will wholeheartedly agree with his judgment that these are artistic masterpieces, which can provide the viewer the same enjoyment that they have provided the collector, the curator, and generations of Jain worshippers.

All photos are by Judy Cooper, courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA).

John E. Cort is Professor of Asian and Comparative Religions at Denison University in Granville, Ohio, USA.

I discuss the replication cult of Jīvantasvāmī in John E. Cort, Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), ch. 4.

This sculpture was also included in the recent exhibition of Jain art at the Rubin Museum in New York City, Victorious Ones. In the catalogue for that exhibition, Sonya Quintanilla also dated this sculpture to the 5th century, but argued for Bihar as its provenance: Phyllis Granoff (ed.), Victorious Ones: Jain Images of Perfection (New York: Rubin Museum of art; and Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 2009), pp. 18889.

See the Digambara sculpture of Śāntinātha from Gujarat now in the Ackland Museum, which dates from 1511, exactly five centuries after the Bhansali Ṛṣabhanātha.

Prof. Dr. John Cort

Prof. Dr. John Cort