Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

The neglected field of the Jaina heritage in Pakistan was revived in 2015-17 through a pilot study conducted by the CoJS of SOAS in collaboration with a research team of the Nusrat Jahan College (NJC) in Rabwah, with additional help of local historians of Jainism in North India[1] In view of the long-term neglect of Jaina sites in Pakistan, and the pressing need of preserving key religious monuments, the project focused on the documentation of the surviving infrastructure, Jaina temples, halls, community buildings, art and writings, along with a historical and demographic study of the Jaina sectarian traditions in the region. Our report summarizes key findings.

Background

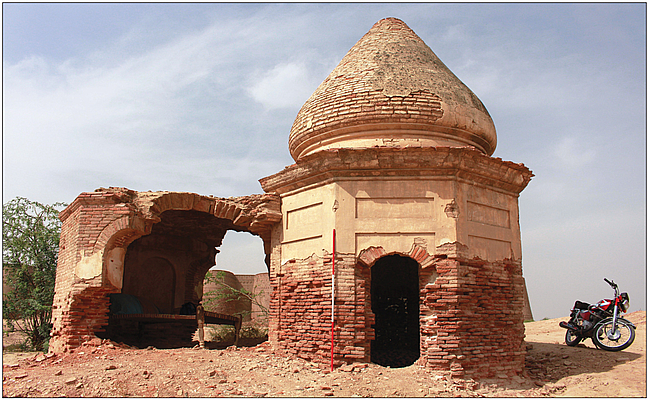

Jainism has a long history in Pakistan, going back to the early historical period, and ending with the partition of British India in 1947. The extent of the Jaina presence in the region in ancient times is yet to be fully assessed.[2] Early Muslim, Sultanate and Mughal periods show only little Jaina activity, predominately in Sindh. Many of the Jain merchants that had settled west of the Rann of Kutch and the Thar desert came under the influence of the Kharataragaccha, which became the dominant Jaina tradition in the region. This was mainly due to the influence of its third "miracle producing" dādāguru Jinakuśalasūri (1280-1332), who toured the small towns and villages of the Indus valley south of Multan for five years between V.S. 1384 and 1389, until his death in Derawar (Devarājapura, Derāur), where a stūpa (samādhi) was erected over his ashes and a "dādābāṛī" surrounding it (Fig. 1).[3] The samādhi was regarded as a miracle working shrine, and became the center of a network of dādābāṛīs dedicated to Jinakuśalasūri, in Halla, Multan, Dera Ghazi Khan, Lahore, Narowal, etc.

Some Jaina presence is notable in Lahore, Sialkot, Gujranwala and Multan during the Mughal rule. The dādābāṛī in Lahore was constructed by Akbar's Osavāla minster Karmacand Bacchāvat (1542-1607) from Bikaner, a disciple of the fourth dādāguru, "Akbarapratibodhaka" Jinacandrasūri VI (1541-1613), who, through Karmacand's intercession, met the Emperor Akbar in Lahore at various occasions in 1592, 1593, and 1594. In 1595 Jinacandra walked, via Multan (Mūlasthāna) and Uch (Uccapuri), to the samādhi at Derawar, to pay his respects, and then back to Rajasthan.[4] Under the reign of Muslim rulers who vigorously opposed image veneration, the influence of the Kharataragaccha declined due to the impact of non-image-venerating (amūrtipūjaka) Jaina mendicant traditions, whose followers took control of most religious properties of the Kharataragaccha in the Punjab at the time of the Partition. Yet, the Kharataragaccha maintained its presence in the desert region of Tharparkar in Sindh, where it still has a few followers today.

The new religious developments in the Punjab were initiated between 1503 and 1551 by the monks Rāyamalla and Bhallo, two disciples of Yati Saravā, sixth leader of the recently formed amūrtipūjaka Gujarati Loṅkāgaccha, who wandered from Gujarat to Lahore, and founded the Lāhaurī- or Uttarārdha Loṅkāgaccha, which became the most popular tradition amongst the Jainas in the northern Punjab in the 17th and 18th centuries. It established permanent seats (gaddī), first in Lahore, and later in Jandiyala Guru, Phagvara, Nakodar, Ludhiana, Patti, Samana, Maler Kotla, Patiala, Sunam, Ambala, Kasur, etc. After a while, image-veneration was re-introduced by the yatis and temples erected in places such as Ramnagar (Rasulnagar), Gujranwala, Sialkot, Pinda Dadan Khan, or Papanakha.[5] Hence, between 1673 and 1693, the orthodox monk Haridāsa split from the Uttarārdha Loṅkāgaccha, joined the Ḍhūṇḍhaka (Sthānakavāsī) tradition of Lavajī in Gujarat, and finally founded his own reformist amūrtipūjaka tradition in Lahore. The tradition became known under the name Pañjāb Lavajī Ṛṣi Saṃpradāya. Under Ācārya Amarasiṃha (18051881) it gradually absorbed the Uttarārdha Loṅkāgaccha, and became the dominant Jaina tradition in the Punjab.[6] At the time of the Sikh expansion individual Jainas played important economic and political roles. And significant mercantile communities established themselves in the Punjab, mainly dealing in cloth, grains, general merchandise, jewelry, and banking. The British period brought in a new system of roads and railways, and Jaina merchant communities took full advantage of it. New settlements emerged alongside these trade routes in Sindh and in the Punjab. In this period, between 1855 and 1875, sixteen mendicants split off the Sthānakavāsī Gaṅgārāma Jīvarāja Saṃpradāya, a small mendicant tradition that was popular in the southwest of Ludhiana, and joined the mūrtipūjaka Tapāgaccha in Gujarat. The main leaders until 1947 were Buddhivijaya (Sthānakavāsī name: Būṭerāya) (18061882), Vijayānandasūri or Ātmānanda (Sthānakavāsī name: Ātmārāma) (1836-1896), and the Gujarati monk "Panjāb Kesarī" Vijayavallabhasūri (1870-1954), whose lineage, the Vallabha Samudāya, was and still is the most active branch of the Tapāgaccha in the Punjab. They regarded temple construction as a necessity for the survival of the Jaina tradition in the Punjab, where Christian missions and Dayānanda's Ārya Samāj had gained support, and inspired their lay-followers to take possession of buildings vacated by the slowly vanishing Loṅkā tradition, and to erect new temples, with adjacent upāśraya for visiting mendicants.[7]

The Sthānakavāsī mendicants were very orthodox at the time. They rejected all "violent" construction work, not only of temples, but also of halls (sthānaka = upāśraya) as "non-" or "anti-religious." Generally, they resided in empty rooms of private houses or in empty buildings judged to be acceptable in terms of monastic codes of conduct. By the end of the 19th century, however, empty buildings of the Loṅkāgaccha yatis were also taken over by the Sthānakavāsīs. The first mendicant in the Punjab who, against internal opposition, advocated the construction of sthānakas, religious schools and libraries, was Muni Khazāncand (1884-1945) of the Pañjāb Saṃpradāya. With permission of "Pañjāb Kesarī" Ācārya Kāśīrām (1884-1945), he started in the 1930s in his birth place Rawalpindi, a city dominated by the Sthānakavāsī community, located at the very edge of the realms of movement of Jaina mendicants, and later in towns such as Gujranwala, Jhelum, Kasur, Lahore, Sialkot, Maler Kotla, and Dhuri.[8]

Figure 1. Samādhi of Jinakuśalasūri at Derawer (Photo: Asif Rana 15.4.2016)

Due to the influence of the charismatic Vijayānandasūri, many Sthānakavāsī śrāvakas had converted to the Tapāgaccha between 1855 and 1945. In turn, the leaders of the Pañjāb Lavajī Ṛṣi Saṃpradāya prohibited intersectarian marriage, and occasionally commensality. As a consequence, the members of the local Osavāla caste were split along sectarian lines for almost a century. With the exception of Sindh, where Poravāḍa and Śrīmālī castes prevailed, almost all Śvetāmbaras in the region of modern Pakistan were Osavālas. They were migrants, who had lost contact with their native Rajasthan, stopped intermarrying with Rajasthani Osavālas, adopted Urdu as their first language, and Persian as their second. Their "mother tongue" Punjabi was only used as a spoken language. Maybe for these reasons the Punjabi Osavālas referred to themselves not as "Osavāla," or "Bīsa / Dasa Osavāla," but as "Bhābaṛās."[9]

In the British period, the Bhāvaṛā communities, became the leading mercantile class in the Punjab, and many villages, bāzārs and mohallās in Pakistan still retain this name. Bhāvaṛā Jains distinguished themselves in the fields of finance, education and publishing early on. Most Jaina heritage sites in the Punjab were once owned by Bhāvaṛā associations. Yet, not all Jains in the Punjab were Bhāvaṛās. Almost as many mendicants of the Pañjāb Lavajī Ṛṣi Saṃpradāya were and are recruited from Brāhmaṇa, Kṣatriya (Rājput), Agravāla, and Jāṭ families as from Bhāvaṛā families, not to speak of mendicants from low castes.[10] Generally, northwest of Ambala no Digambara communities can be found. The small minority of Terāpanth Digambara Agravālas, who established small communities and settled in towns such as Rawalpindi, Sialkot, Lahore and Karachi were suppliers of the British military. Their temples were located in the cantonment areas. Most, if not all of them have been demolished after 1947. Only few towns such as Multan (which once had a bhaṭṭāraka seat) featured old Digambara temples in the bāzār areas of the walled city.

Before Partition, the Jaina community was less than one percent of the total population in areas which were included into Pakistan. At the eve of partition almost the entire Jain population migrated to India, except for a few households in Nagarparker. Some Jainas are said to have converted to Islam.[11] But most left in the protective presence of the British Army and, in exceptional cases, of monks, such as Vijayavallabhasūri, who were forced to break their monastic rules and to use trucks, trains or planes, to save their lives. The refugees mostly settled in the Indian Punjab, Hariyana, Rajasthan, U.P., and in Delhi. They took with them their portable religious art and libraries, leaving behind empty buildings, shelves, and niches.

In 1960, the Government of Pakistan established the Evacuee Trust Property Board (Awqaf) for the protection and administration of properties attached to educational, charitable or religious trusts of migrated Hindu and Sikh communities. For the Muslims in Pakistan the Jainas were "Hindus," and the Jaina religious heritage is therefore also generally being considered as "Hindu." Only with prior information at hand can one hope to find a mention of Jaina sites in Awqaf's records, and this is not always the case. Non-religious heritage buildings have long been occupied by locals. In some cases Muslim migrants from India exchanged properties with migrant Jain communities from Pakistan, as in the case of the Shri Amar Jain Hostel Lahore, now located in Chandigarh. After Partition, no research on the Jaina heritage in Pakistan has been conducted. Hīrālāl Duggaṛ (1979: 354) hence noted that "at the present time there is no information on the condition of all the temples and institutions in Pakistan." Similar observations were made by R. K. Jain (2003: 2): "The present status of Jain Temples, Upashrayas and Sthanaks is generally not known. Whereas Ghar-Mandirs, Upashrayas and Sthanaks have by and large been usurped and put to different uses by the Pakistan Authorities and Public, the Sikhar Band Mandirs still seem to exist. Since there are no Jains left in Pakistan, these Temples are not being worshipped at all." Our research project tried to answer the question as to the current state of Jaina temples and institutions.

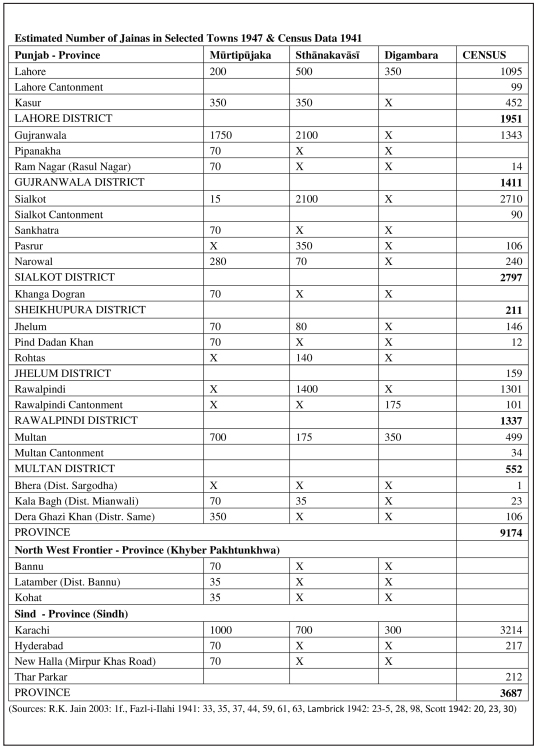

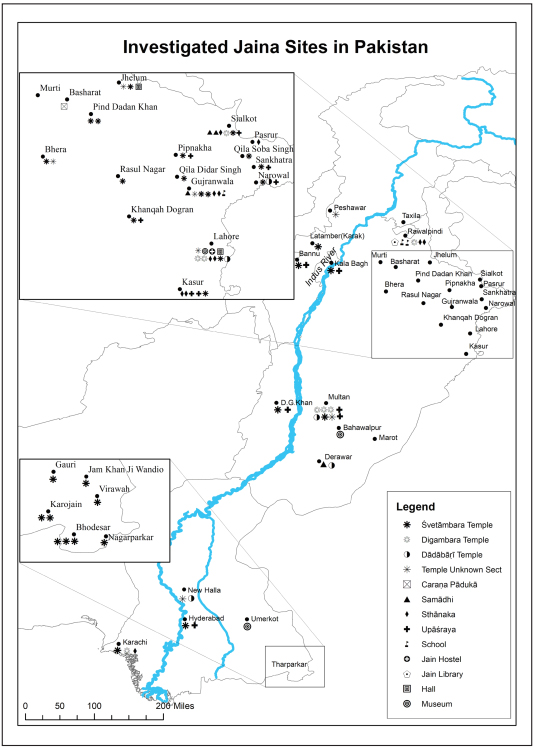

In the first phase of project a thorough literary review was conducted and relevant information on pre-Partition demographics and sites of the Jaina community collected from available literary sources, and through interviews. Thus a list of about one hundred potential Jaina sites at thirty locations in the Punjab, North West Frontier (KPK) and Sindh was prepared. Subsequently it was modified and reduced to approximately ninety locations in the end. These sites include Digambara and Śvetāmbara temples, dādābāṛīs, sthānakas, samādhis, libraries, schools, hostels, as well as mohallās identifiable through their Jaina or caste names, etc. Most of these structures were built or renovated during the British period, between 1865 and 1947. During the literature review demographic trends of the in Jaina populace of Pakistan were traced through a study of available Gazetteers and some other research publications of the British era. Significant information is available in these sources about demography, caste background, and distribution of the predominately city-dwelling Jaina population, concentrated in particular quarters,[12] from 1819 to 1947. The official data, suggesting the existence of some 12,861+ Jains in the region in 1941, is incomplete, and not reliable.[13] It also does not offer a breakdown of the religious affiliation of the Jaina population. A tentative overview of the geographical distribution of the three main sectarian traditions in 1947: the Sthānakavāsī traditions (especially the dominant Pañjāb Lavajī Ṛṣi Saṃpradāya), Tapāgaccha & Kharataragaccha, and Terāpanth Digambara, is offered by the table on the facing page.

The information is based on estimates of Jaina refugees in India. It was collated by R. K. Jain in 2003 "from some elderly people," and on the basis of his "own memory," on request of the Anandji Kalyanji Pedhi in Ahmedabad. As admitted by the compiler R. K. Jain, the number of Sthānakavāsīs is underestimated. The numerical proportions may be relatively accurate. But in some cases the low figures seem only to make sense if taken to refer to houses rather than persons.[14] The corresponding census data, included in the table, are, however, equally low. The research focused on a survey of the built heritage.

A team of NJC researchers travelled thousands of kilometers in Punjab and Sindh, mapping and recording identifiable Jaina sites in the districts of Lahore, Qasur, Sialkot, Chakwal, Khoshab, Bhera, Gujranwala, Farooqabad, Jhang, Chiniot, Multan, Bahawalpur, Marot, Rahimyar Khan, Karachi, Nawab Shah, Kunri, Tharparkar, and Nagarparkar. Observable features, murals, inscriptions, icons and sculptures, street views, etc., were recorded as much as permitted access allowed. All structures were photographed, and a database of more than three thousand photographs was created, planned to be put online, together with a spreadsheet with descriptive, background, and interview data.[15]

Inscriptions of the British era are found on some Jaina buildings in Punjab. They are mostly in Devanagari script, but also in Persian script. In some cases Urdu and Hindi bilingual or Urdu, English and Hindi trilingual inscriptions are found. Occasionally the words are in Rajasthani or Gujarati. In a few cases, local Laṇḍā scripts are also evident, along with above mentioned languages and scripts. Some Jaina edifices provide a glimpse into the art of religious painting popular in Sikh and British periods, presenting scenes from Jaina religious history, and sometimes explaining them with short inscriptions. Yet, with the notable exception of the temple in Gauri, most surviving inscriptions and mural paintings are reduced to small fragments of little historical or aesthetic value.

Since many investigated sites were found ruined, demolished, or could not be clearly identified, the interpretation of the collected data relies largely on background information available only in India in oral and written form, and to local historians, who were interviewed wherever possible. Ravinder K. Jain of Maler Kotla motivated migrant Jaina community members to help identifying further Jaina heritage sites in Pakistan, confirm or disconfirm collected information, and to supply supplementary evidence. Additional interviews with migrants were conducted in India by the PI in Delhi, Meerut, and Jaipur. On the basis of the written and oral record, many of the surveyed sites could be re-connected to particular social groups, religious traditions, and historical events.[16] Not all sites indicated on the map of investigated locations (facing page) still exist, or can be unequivocally linked to the Jaina tradition.[17] The initial survey of the built heritage brought this fact to light that Jainism has lost its footing in modern Pakistani society decades ago. Many temples, under the administration of the Evacuee Trust Property Board, have been allotted to the local families who reside there. Houses were assigned to new residents, and community buildings given on rent by the Evacuee Board without maintaining any separate record, and many temples and halls, many of them built shortly before Partition, were simply demolished. Most of the remainder are left to the process of natural decay.

Survey of Museums, Libraries, and Archives

The last stage of this pilot study was to survey museums, libraries and archives for Jaina heritage. The Umarkot museum in Tharparkar and the Bahawalpur museum yielded very little in this regard. The Lahore museum has the best collection of Jaina artifacts and structures anywhere in Pakistan. The artifacts from Murti are potentially important. They were brought into the museum right after the site was excavated by Stein. Yet, most of the collection is in storage and inaccessible. The other notable collection in the Lahore museum is of caraṇa-pādukās. The most impressive items belong to Gujranwala Jaina sites, and were transferred from there to the museum to prevent their destruction. There are also impressive Jaina statues on display, but no record of their whereabouts exists.

Apart from one Jaina manuscript housed in the Lahore Museum Library, there is a big collection of Jaina manuscripts in Punjab University's Woolner Collection. Other than the old catalog published by the Punjab University, there is a newly developed database produced by a joint project of the Punjab University and the University of Vienna, and Geumgang University.[18] Most other Jaina manuscripts and books held by Jaina institutions were transferred to India around 1947. Most of these sources are now preserved by the B. L. Institute in Delhi. Verbal accounts tell also of missing and destroyed materials which were never recovered.

Some pamphlets published in Urdu as part of the Jaina Tract series from Lahore, Delhi and Ambala are found in the Khilafat Library Rabwah and the Punjab Public Library Lahore. The Khilafat Library Rabwah, Punjab Public Library, Punjab University Library, Iqbal Public Library Lyallpur, National Archives, National Documentation Center and the Punjab Archives all have vast collections of books in Devanagari and Gurumukhi scripts.[19] Since there are no catalogue records of these materials, nothing can be presently said of the Jaina books in these collections. The unorganized nature of these archives demands a full project of cataloguing or sifting through these archival materials to locate any material relevant to Jaina Studies.

Summary

This first systematic field survey and mapping of the Jaina heritage in Pakistan after 1947 brought to light a wealth of information about the current state of the built heritage, sacred art and literary contribution of the Jainas. The picture is not rosy. The surviving structures are generally in miserable condition. The Temple at Multan is mostly intact as it was turned into a Madrasa and its management takes good care of the building and the paintings. One temple in Farooqabad is occupied by a local merchant who takes good care of it. The temples in Tharparkar are not used for Jain worship anymore, but the structures of some temples, in Bhodesar, Nagarparka, and Virawah are intact, and worth preserving, in particular the famous paintings of the Gauri temple, which are in urgent need of restoration. Most murals in Jain temples have either been vandalized or left to decay.

After Partition, Jainism and Jaina communities of Pakistani Punjab and Sindh vanished from the collective memory. There are almost no references of Jainism or Jains in the local literature. History books on Bhera, Sialkot and Lahore have a few lines on Jains here and there. Old people above the age of 80 still retain memories of their Bhāvaṛā neighbours. The lack of interest and records of the migrated Jaina families in India and fading memories is another problem. Only a few Jaina households in Nagarparkar remain. But they are unwilling to disclose their religious identity. In the light of this pilot study, the following conclusions have been reached.

1. The Jaina built heritage in Pakistan from the 19th and 20th centuries is in miserable condition and requires a swift transfer from the control of Awqaf to the Department of Archaeology or to the Ministry of Culture, to facilitate the preservation of religious monuments of historical significance.

2. The labelling of artifacts displayed in museums should be reviewed, since generally no clear distinction between "Hindu" and "Jaina" objects is made.

3. Libraries and archives should be encouraged to catalogue work in Devanagari and Gurumukhi scripts.

4. Results of this pilot study suggest that careful archaeological surveillance could bring to the surface further evidence of Jaina activity. An archaeological survey to locate and study pre-Muslim Jaina heritage in Pakistan should be conducted.

5. A Department of Jaina Studies should be established in a federally run university.

References

Ahmad, Muzaffar. "Newly Discovered Jaina CaraṇaPādukās in Chel-Abdal Chakwal." Jaina Studies: Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies 10 (2015) 4042.

Cāvalā, Kāṃśī Rāma. Svāmī Śrī Khazānacandajī [Kalyāṇacandajī] Mahārāja. Hindī Anuvādaka: Syāma Lāla Jain. Dhūrī Maṇḍi (Paṭiyālā Sṭeṭ): Lāla Dūrgadāsa Jain, (1945) 1947 [Original in Urdū].

Duggaṛ, Hīrālāl. Madhya Eśiyā Aura Pañjāb Meṃ Jainadharma. Dillī: Jaina Prācīna Sāhitya Prakāśana Mandira, 1979.

Duggaṛ, Hīrālāl. Saddharmasaṃrakṣaka: Muni ŚrīBuddhivijaya (Būṭerāyajī) Mahārāja Kā JīvanaVṛttānta. Godharā: Bhadraṅkarodaya Śikṣaṇa Ṭrasṭ, 2013.

Fazl-i-Ilahi, Khan Bahadur Sheikh. Census of India. 1941, Vol. VI: Punjab-Tables. Delhi: Government of India Press, 1941.

Flügel, Peter. Sthānakavāsī Śvetāmbara JainaTraditionen in Nordindien: Manoharadāsa-, Lavajī Ṛṣi-, Harajī- und Jīvarāja-Saṃpradāya. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz (Forthcoming).

Jain, Raj Kumar. "Jain Temples in Pakistan and the then Jain Population." Letter to Sheth Shrenikbhai (Sheth Anandji Kalyanji Pedhi), Delhi 18.7.2003.

Jain, Raj Kumar. My Life Journey: Through the Memory Lane. Delhi 31.5.2015 (unpublished manuscript).

Jain, Ravindar & Puruṣottam Jain. Purātana Paṃjāb Vica Jaina Dharama. Prerikā: Savaraṇa [Svarṇa] Kāntā. Māler Koṭlā: Paccīsvīṃ Mahāvīra Niravāna Śatābadī Saṃyojikā Samiti, Pañjāb, 1974. http://www.jainworld. com/JWPunjabi/puratan%20punjab%20vich%20 jain%20dharm/index.htm

Lambrick, H. T. Census of India. 1941, Vol, XII: SindTables. Simla: Government of India Press, 1942.

Marshall, John Hubert. Taxila: An Illustrated Account of Archaeological Excavations carried out at Taxila under the Orders of the Government of India between 1913 and 1934. Vols. I-III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951.

Qaisar, Iqbal. Ujaṛe Darāṃ De Darśan: Pākistān Vicale Jain Mandirāṃ dī Tavārīkhī Fikśan (Visiting Deserted Doors: Historical Fiction of the Jain Temples in Pakistan). Lahore: Pakistan Punjabi Adabi Board, 2018.

Samudrasūri, Ācārya. "ŚrīmadViyayānanda Sūriśvarajī Ke Śiṣyādi Kā Paṭṭaka." Navayuga Nirmātā: Nyāyāmbhonidhi Śrī Ācārya Vijayānanda Sūri Śrī Mahārāja Kī Jīvana Gāthā. By Vijayavallabhasūri. Pariśiṣṭa 2: 425-438. Sampādaka: Haṃsarāja Śāstrī. Ambālā: Ātmānanda Jaina Mahāsabhā Pañjāb, 1956.

Scott, I. D. Census of India. 1941, Vol. X: North-West Frontier Province. Simla: Government of India Press, 1942.

Sumittabhikkhu (Sumitra Muni, Sumitra Deva). Kaśmīr se Karācī. Prakāśaka: Viśveśvarddayāla Jaina. GuṛgāṃvChāvanī (Pañjāb): Mālik Naukār Āyran Sṭor, 1949.

Vinayasāgara, Mahopādhyāya. Kharataragaccha Kā Bṛhad Itihāsa. Saṃyojana: Bhaṃvaralāla Nāhaṭā. Sampādaka: Śiva Prasāda. Dvitīya Samskaraṇa. Jayapura: Prākṛt Bhāratī, 2004/2005.

The work was sponsored through a generous gift of Baron Dilip Mehta of Antwerp. Key contributors were PI Peter Flügel (SOAS), Mirza Naseer Ahmad (NJC), coordinator of work in Pakistan, and RO Muzaffar Ahmad, who analysed data from published sources in Urdu and English and from museums in Pakistan and planned the field research. Fieldwork was conducted and written up by Asif Rana, and maps were produced by Naeem Ahmad and Tahira Siddiqa (all NJC). Ravinder Jain of Maler Kotla and Purushottam Jain of Mandi Gobindgarh in India provided invaluable background information about locations of Jaina sites in Pakistan, based on prior research (Jain & Jain 1974) and communications from Sādhvī Svarṇakāntā (1929-2001) (born in Lahore), Sādhvī Arcanā (family from Rawalpindi), Mahindra Kumar Jain (Co-researcher of the late Hiralal Duggar in Panch Kula), and others, and from Iqbal Qaisar in Lahore, who conducted independent research on the same subject. See Qaisar (2018). Valuable information was also supplied by Noel Q. King (1922-2009) of Corralitos in California (born in Taxila), who in 2003 researched the Jain temples and institutions in Pakistan but had his notes stolen on a train, and Raj Kumar Jain (born in Jhelum), the principal stalwart of the Śvetāmbara refugee community in Delhi. They were interviewed by PI on 8.6.2005 and 23.2.2017 respectively. Further interviews were conducted with informants in Meerut, Jaipur, Bikaner, etc.

For an overview, see Duggaṛ (1979). Fresh archaeological discoveries continuously increase our understanding of the Jaina past in Pakistan. Members of the research team located caraṇa-pādukās of uncertain date in Chakwal (Ahmad 2015), and in Nagarparkar recorded on site sculptures, of relatively recent origin, being excavated by the Department of Archaeology Sindh.

After Partition, relics, sand and stone, were moved from the site to the Derāur Dādābāṛī near Jaipur (Vinayasāgara 2004/5: 197).

On the history of the amūrtipūjaka Jaina traditions in the Punjab and adjacent regions, see Flügel (forthcoming).

See Duggaṛ (2013: 204f.) on Buddhivijaya's initiatives and temples already existing prior to this.

Sumitta Bhikkhu (1949: 195) derives the term from the compound bhāva-baṛā ("great belief"), while Duggaṛ (1979: 236f.) opts for the name of the village Bhāvaṛā, south of Lahore, where Karam Chand Bachhawat had erected a foot-image (caraṇa-bimba) of Jinakuśalasūri, which became the local focus of the popular dādābāṛī cult.

Ravinder Jain 8.3.2018. Sumittabhikkhu 1949: 417 reports of 500 Sthānakavāsī "houses" in Karachi in 1945, pointing to a figure of ca. 2500 Sthānakavāsīs. Figures for the North Western Frontier were extremely low and were excluded from the 1931 Census Report.

The findings of the recently published narrative work of Iqbal Qaisar (2018) Visiting Deserted Doors: Historical Fiction of the Jain Temples in Pakistan (in Urdu & Forthcoming English Version), are also being taken into account. Based on a long-term collaboration with Ravinder Jain and Purushottam Jain, the book is not quite as "fictitious" as it pretends to be

Dr. Peter Flügel

Dr. Peter Flügel

Muzaffar Ahmad

Muzaffar Ahmad