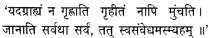

Acharya Pujyapad explaining “ I ” has said: “ I ” is that who does not accept the unacceptable, does not give up the acceptable and knows everyone fully. “ I ” does not exist where the unacceptable is accepted, the acceptable is given up and the partial is known.

A non-violent society has the same characteristics as “ I ”. Conditions determining one's permanent nature are not to be renounced. It is conditions, which give rise to a particular state of mind that, are to be renounced. Anything beyond “ I ” has to be given up. This is what Anuvrat is.

Question: During camps organized to practise Anuvrat discussions take place on agriculture, production, implements, etc. Good food and drinks are served and people are well entertained. Can this be regarded as spiritual practice? Proportionately less attention is paid to meditation, observance of silence etc. Are these camps places of spiritual practice or of amusement?

Answer: Why is it believed that spiritual practice is possible only within traditionally accepted limits and not outside them? Meditation, observance of silence and physical relaxation are indeed spiritual practices but are speaking, eating, drinking, sitting, and standing not spiritual practices. Is good mutual behaviour not a spiritual practice? If you think they are not, you have not at all understood the meaning of spiritual practice.

Once two rulers went hunting, riding their own chariots. The chariot of one of them burnt down, while the horse of the other died. Both became disabled and unselfreliant. Returning from the forest become difficult. Both cooperated with each other. One gave his chariot and the other his horse. A chariot was ready and riding it both returned to the town. It is called Dagdhashvarath. The same is true of spiritual practice. In its fragmented or partial form it does not bear fruit or liberate the practitioner. The integrity of spiritual practice is questioned by those who insist that it is possible only in a particular place, at a particular time and through a particular activity and not otherwise. One of the incongruities of life is spending two hours in spiritual practice and the remaining twenty-two hours in non-spiritual pursuits.

It does not help in creating faith in religion in the hearts of the people. In fact, Anuvrat implies that there be no incongruity in life from the time one gets up in the morning till one goes to bed, and there be uniformity of spiritual practice at all times of day and night. Anuvrat manifests the nature of spiritual practice. Even then in the phrase "Anuvrat Sadhpa Shivir' (Camp for Anuvrat Spiritual Practice) the words 'spiritual practice' have been appended to Anuvrat. In Sanskrit grammar the word Veepsa is used which means Vyaptumichcha, i.e., the desire to permeate or extend. In Veepsa saying the same word twice or four times is not considered a fault. It is in this sense (of Veepsa) that the words 'spiritual practice' have been appended to Anuvrat.

Not that meditation, Yogic postures etc. are not essential. But they alone do not constitute spiritual practice. Spiritual practice consists in remaining spiritually alert in what one does throughout the day. A man who stayed in the camp recently was very religious. Earlier he used to practise with great faith meditation, silence etc. for four to five hours. But he was indifferent to good behaviour. As a result his wife and all members of his in-laws' house were angry with him. In fact, as a result of his behaviour, they developed distaste for religion. A man cannot be religious if he is responsible for making others dislike it. But his stay in the camp and practice of spirituality there changed his ideas about spiritual practice. His life was transformed. As soon as he became alert about the tightness of his behaviour along with doing his spiritual practice and began to induct spirituality in everything he did, all around him became happy.

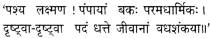

It is in vain to believe in the possibility of doing meditation of life is devoid of humane behaviour, if ideas lack clarity and if one is full of perverted beliefs. It is a different matter if spiritual practice is viewed in a partial and fragmented manner. Fasting, meditation and observance of silence are means. The success of spiritual practice will be in proportion to the diminution of distance between means and ends. A Sthitpragya (person gifted with unshakable mental equilibrium) discourses on various themes throughout the day, yet he is in reality silent. How can sitting tonguelessly under the spell of anger or confrontation be termed silence? If it is, then even a heron can be called a meditator. Under this very illusion Ram praised the heron:

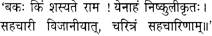

Hearing Ram say the above words a fish said:

A sulky daughter-in-law went and sat down in a corner. She did not eat at all. Shall we call it fasting? Spiritual practice is neither in not doing something, nor in doing something. It lies in inner awakening no matter whether accompanied with activity or inactivity.

Acharya Mahaprajna

Acharya Mahaprajna