Tara Sethia was raised in the faith tradition of Jainism, a religion that has stressed ahimsa, or nonviolence, since its founding 2,600 years ago in her native India.

But living in the United States, she says, she found that belief neglected and often misunderstood as a wimpy act of surrender.

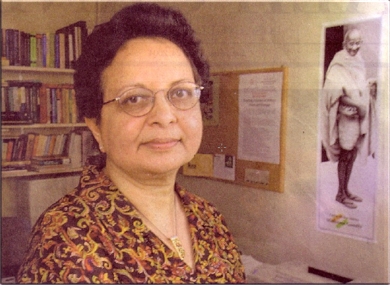

"History books always explain change in terms of war, as if it is violence that will bring results," said Sethia, a history professor at California State Polytechnic University in Pomona.[California, USA]

"I began to wonder why the history of nonviolence is marginalized. Why don't kids know about Mohandas Gandhi?” she asked, referring to the Indian leader who successfully used nonviolence to bring his nation independence from Britain.

Her questions became a vision, and now a dream fulfilled: Cal Poly has officially approved her proposal to establish a center to teach about nonviolence through college courses, teacher training, community gatherings and conferences. Supported through private donations and some public funding, the Ahimsa Center plans to hold its inaugural conference next month. Among the scheduled speakers are such leaders in the field as A.T. Ariyaratne, a social activist known as the "Gandhi of Sri Lanka," and Thai Buddhist leader Sulak Sivaraksa, founder of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists.

The center's establishment is the latest sign that the nonviolence movement is alive and well in the face of war, terrorism and enormous increases in U.S. military spending. The Iraq war in particular, which kicked off the largest peace rallies in world history, has prompted "a searching for ways to turn this around and solve our problems without war," according to Richard Deats of the Fellowship for Reconciliation, a faith-based peace group headquartered in New York.

Near Bakersfield, the family of the late farm labor activist Cesar Chavez is scheduled to unveil the new National Chavez Center today - a place the family envisions will showcase his teachings and practice of nonviolence. The center will house a memorial garden and visitors center, which are near completion, and, later, a retreat center, a museum and a library.

Across the country, new coalitions are planning events on nonviolence, says Mary Ellen McNish, general secretary of the pacifist American Friends Service Committee. And groups like the Fellowship for Reconciliation and the Ohio-based Center for Applied Conflict Management say requests for nonviolence training are increasing from churches, schools and peace centers.

Besides concerns over the Iraq war, activists say, another factor pushing interest in nonviolence is the United Nations' declaration of the years 2001 to 2010 as a "Decade for a Culture of Peace and Nonviolence." Originally conceived several years ago by 20 Nobel Peace laureates, including the Dalai Lama, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Mother Teresa, the declaration has prompted several faith-based organizations and peace groups to plan activities.

The values of peace and nonviolence are rooted in every major faith. McNish, for instance, says her pacifism stems from the Quaker conviction that "there is that of God in every person, and you do no harm to other people." For Jains, the prohibition against killing stems from their belief in karma and reincarnation - that a life of good acts is necessary to escape the cycle of death and rebirth, the ultimate goal of every person, according to Sethia.

But nonviolence is also successfully used for social change without the religious underpinnings. "One can use it as a pragmatic tool superior to violence," said Patrick G. Coy, assistant professor at the Conflict Management Center of Kent State University in Ohio.

Such pragmatism has prompted such people as Mahmood Ibrahim, a native Palestinian and chairman of Cal Poly's history department, to call for an end to the intifada's violence against Israel. Ibrahim, one of a growing number of Palestinian intellectuals urging a switch to nonviolence, said suicide bombings have only allowed Israel to justify its own violence. In contrast, he said, the nonviolence of the first intifada in the late 1980s was more successful in garnering international sympathy and engaging Israel in a peace process.

The professor said he planned to urge the new approach at the Ahimsa Center's conference scheduled for May 14-15 at Cal Poly. Other speakers also will share experiences in using nonviolence and teaching about it.

As a Jain, Sethia grew up with the traditions of ahimsa, following such vows as nonviolence, truth, sexual restraint and detachment as a path to "moksha," or spiritual liberation. A strict vegetarian, Sethia also studied the Jain, Buddhist and Hindu concepts of nonviolence as a scholar specializing in Indian history. In 1979, she came to Southern California to earn her doctorate in the field at UCLA.

Her idea for the center, she said, was enthusiastically received by the university - even though Cal Poly is better known for engineering and other technical subjects. But because of state funding cutbacks, Sethia said, she has had to raise money for the initial five-year, $350,000 budget largely from private donors. In four months she has raised about $200,000 in cash and pledges, some from prominent Indian American entrepreneurs in the Silicon Valley.

"I believe it's the power of the idea that has created so much enthusiasm," she said, stressing that the center is nonsectarian and open to all. But, Sethia added, the center has much work to do to bring the teachings of nonviolence to the mainstream.

Among other things, proponents say they still struggle with the image in some quarters that nonviolence is a passive, even cowardly approach. Paul Chavez, the legendary labor leader's son, said his father confronted that perception in dealing with the pride and machismo of many Latino farmworkers.

"He wrote that the strongest act of manliness was to sacrifice ourselves for others in a totally nonviolent struggle for justice," Chavez said. "He was chastising big, macho guys who believed that the way you show courage is to beat the hell out of someone."

Another misperception, Sethia said, is that nonviolence is ineffective.

She and others say that most of the biggest social and political changes in the latter half of the 20th century were achieved largely through nonviolence, including the Vietnam War protests, the civil rights struggle and the antiapartheid movement.

Thanks to growing concerns about the Iraq war, proponents of nonviolence say the movement is poised for another leap forward.

"What we're seeing now is a reawakening of that slumbering giant," McNish said.

Teresa Watanabe

Teresa Watanabe