Anekantavad as a Physical Reality

Lecture delivered at the International Seminar on " Anekanta: a dialogue for human concerns" held at Vadoadara, December 6-9th, 2002, organized by Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, Ladnun,

Anekantavad is the corner stone of Jainism around which the whole philosophy and religion have developed. It is as fundamental as the Karmavad or Causality in physics. It has been mentioned in the scriptures that one who is "equipped" with Anekanta attains samyakdrishti and Kewalgyan (see eg. Samayasara). So it must be very profound knowledge. But what is anekanta? It is nowhere defined clearly. Its social importance has been emphasized, time and again, in the context of today's problems facing the communities, the nation and indeed the whole world and it is interpreted to mean co-existence and cooperation by various sects, factions or religious groups although they may be ascribing to different faiths and philosophies. Its importance in the spiritual world has been emphasised in Jain scriptures to explain undescribable spiritual phenomena and entities. The question I want to discuss here is whether the nature follows "Anekantavad". In other words, "Is Anekanta confined to the philosophical and social domains only or it is also a fundamental law of the physical world? In philosophical or social domains one has the freedom of choosing a doctrine, which he thinks is right according to his concepts but if the nature follows a law, it becomes a fundamental law which one cannot violate, even if one wishes. Therefore naturally the question arises whether Anekantvad is something which governs the physical processes operating in the universe too or it is merely a philosophical concept. To do so, we will first have to define Anekantvad rigorously.

Let us begin by asking what is meant by Anekantavad. It is considered as a doctrine which is usually defined in a negative way as "non-absolutism" just as some other Jain concepts like non-violence is defined. It has been variously described as the theory of many-foldedness, many-facetedness, non-equivocality and syādvāda. Saying that Anekantavad means non-absolutism does not convey much except to say that there is nothing like the absolute truth or absolutely or uniquely correct perspective. Many-foldedness or many-facetedness, imply that there could be many perspectives or points of view of a thing or a concept. Some of these views may even be contradictory to each other. So, it may be taken to imply that everyone is free to hold his own views and this concept has been developed to imply tolerance, accommodation of other's views and nonviolence. Some times anekāntvād is contrasted with Ekantvad which stands for definite and categorical asserted philosophical position. This may be true in the fields of philosophy and sociology where anekantvad and ekantvad can coexist but in the physical realm, if nature follows anekantvad, there would be no place for ekantvad. Unlike philosophy and sociology, Anekantavad and Ekantvad are contrary terms in the realm of physical nature. If one is true, the other is false.

If we wish to address to the question posed above, then I may have to transgress the definitions given in scriptures, which have been mainly used in philosophical or spiritual context and I may be compelled to take the liberty of going beyond these well debated definitions so that we can look at the physical universe from this point of view. We therefore make two propositions: first as an axiom or principle and second as a testable hypothesis.

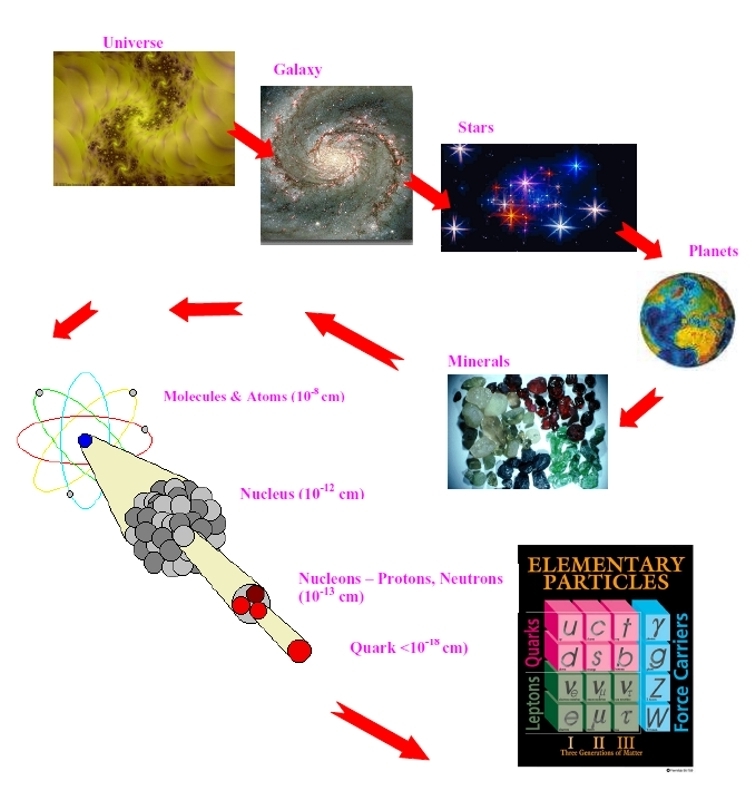

- Many (anek) cannot originate from One (Ek).

It is said that the truth is interwoven in the universe. So let us look at the universe from the point of view of these propositions. The Universe is the biggest object we know (by definition), formed some 15 billion years ago, as observationally shown, consistent with the "Big Bang" theory. We will not go here into the controversies of the state of the Universe before the Big Bang, or debate between other ideas of steady state, oscillating or multiple universes, but rather accept, for the purpose of the present discussion, that there is one universe which contains everything, although this idea of one universe may not be consistent with Anekantavad. Anekantavad probably implies many Universes. None the less, continuing our attempt to understand the nature of the Universe, we begin with what we know of the Universe. It consists of some 200 billion galaxies, each of which consists of some 100 billion stars and even more planetary (rocky) objects (Figure 1). All the matter in the Universe is made up of some millions of chemicals, thousands of minerals and, in addition, there is the most important component, life. As far as we know at present, life probably originated from the inanimate matter and exists only on the Earth, although there are reasons to believe that it should also occur throughout the universe, wherever suitable conditions exist. The visible universe with all its diverse components is basically made up of some 118 elements (92 stable and long lived radioactive elements and about 26 short lived elements, synthesized by nuclear reactions, but not naturally occurring on Earth). The vast tree representing diversity of matter and life in the universe formed out of just a hundred odd elements, acting as the basic bricks compelled philosophers to hypothesise that the root cause of all the elements may be some smaller number of elementary particles, may be even just one. This principle was at the heart of Dalton's atomic theory, a concept erroneous according to Anekantavad. The initial search for these building blocks of matter was encouraging and was even taken to support this idea of one basic constituent of all matter, another concept which is erroneous according to Anekantvad. Initially hydrogen was recognized as the atom out of which all the known elements could be formed. As the search for the ultimate constituents of matter continued, three particles, proton, electron and neutron were discovered from which all the 100 elements and their 2000 isotopes could be formed. This trinity could be used in different proportions to build the whole universe (except life).This strengthened the belief in Ekantvad, ie one can give rise to many but as further research continued, serious problems arose. By the nineteen sixties, using large high energy accelerators, scientists were able to discover hundreds of elementary particles. Hundreds of elementary particles could not be the building blocks for making just a hundred elements and therefore the hypothesis was made that the so called elementary particles should be made up of only a few fundamental entities.

The visible universe or the gross world follows the classical physics. Basically, the state of the universe can be determined by summing up the state of all its components. If mass (m), velocity (v) and position (x) of all the components are known, the state of the system can be determined.

Whole = Ʃ (m,v,x)parts

However as we go to the level of elementary particles, the classical physics fails to hold and quantum mechanics has to be adopted and some new principles come into play. Thus there is a natural division between physical laws of classical physics, applicable to the gross universe, bigger than an atom, and the quantum physics applicable to the subtle world, consisting of elementary particles and the micro universe. In classical physics, a proposition that "a particle is at position x" is either true or false. In contrast, in quantum physics, the best that can be said is that if a measurement of position is made, the probability that the particle will be at a position x would lie between 0 to 1.

Quantum mechanics is the crowning glory of the 20th century physics. What does it say? Physicists were forced to develop it because the laws of the so called classical physics ie of macro world are not found to be valid in the micro world. After a lot of debate to understand the quantum behaviour, Feynman, a Nobel Laureate and one of the greatest minds of the modern era said "nobody understands quantum mechanics… I am going to tell you what nature behaves like. If you will simply admit that may be she does behave like this, you will find her a delightful, enchanting thing. Do not keep saying to yourself... 'how it can be like that?' Because you will get into a blind alley from which nobody has escaped. Nobody knows how it behaves like that. "Some Quantum phenomena cannot be described in a language, they are "crazy beyond words", and cannot be comprehended by common logic.

New principles have been used to define the behaviour of particles in the microworld. The principle of symmetry and complementarity seem to play some role in the macroworld too but in the micro world, we have, in addition to these principles, the Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, Pauli's exclusion principle and so on. Before we discuss the quantum behaviour, we will briefly introduce some of these principles which have helped us in understanding the nature of the universe.

- Principle of Complementarity

- Principle of Symmetry

- Uncertainty Principle

- Exclusion Principle

Principle of Complementarity

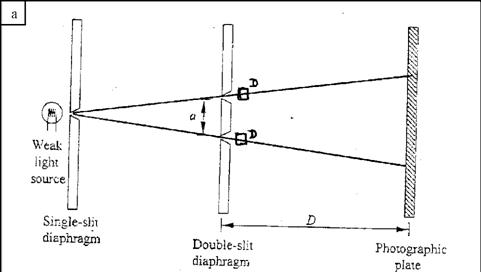

Principle of SymmetryThe principle of complementarity implies that opposites are complementary and, together they describe the real world. Niels Bohr who propounded the basics of quantum mechanics had great difficulty explaining it, and he did it through his principle of Complementarity., considered to be the most revolutionary and significant concepts of modern physics. The Western philosophers and scientists had a lot of difficulty in understanding and developing quantum mechanics. Some experiments gave contradictory results, implying that sometimes light or a photon (or electron) behaves like a compact object i.e. a particle and sometimes like a wave such as a ripple we see in a pond. In the famous two slit experiment, a beam of photon shines through two slits and hits upon a photographic plate behind the slits. The experiment can be run in two ways: one with photon detectors right beside each slit so that the photons can be observed as they pass through the slits and or with detectors removed so that the photons can travel unobserved. When the detectors are in use, every photon is observed to pass through one slit or the other and essentially the photons behave like particles. However, when the photon detectors are removed, a pattern of alternating light and dark spots, produced by interference of light are observed indicating that the photons behave like waves, with individual photon spreading out and surging against both the slits at once (Fig. 2). The outcome of the experiment then depends on what the scientists want to measure. But how do photons "know" or realize that they are being observed by the detectors remains a mystery. In the living world, change of behaviour when being watched is a well-known psychic phenomena but change of behaviour in the material world is baffling. Does it mean the particles have a psyche? Scientists don't agree with this interpretation but have explained it on the basis of plurality of attributes.

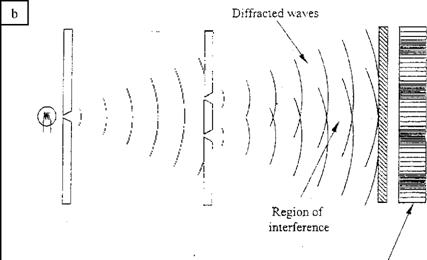

This dual behaviour of a photon could not be reconciled because of the basic nature of waves and particles were considered to be exclusive or different from each other. Bohr explained this by saying that contradictory behaviour is complementary and used the Chinese concept of Yin and Yang (Fig. 3), which are both opposite but exist together and are required for sake of completeness. This is easily understood in the framework of Anekantvad which accepts that opposites and extremes allow us to learn the true nature of reality. As propounded in Jainism, reality can manifest different perspectives at different times. It may be noted that, in contrast, Buddhism avoided extremes and Buddha favoured the path of the Golden mean to reconcile contradictory views.This is a fundamental difference between Jainism and Buddhist approach.

Thus complementarity became the cornerstone of quantum behaviour, to which we will revert in some detail later on.

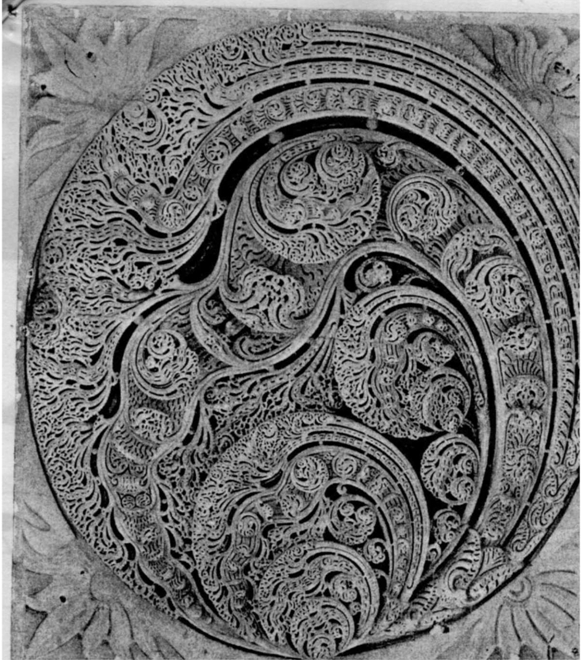

Uncertainty PrincipleNature loves symmetry. Symmetry has been the backbone of understanding nature. The life forms, galaxies, planets, trees, molecules, atoms etc are all symmetrical. There are many forms of symmetry. Left and right symmetry, mirror symmetry, time symmetry and so on. Pictorially, symmetry has been very elegantly depicted in a sculpture found in the Jain temple at Ranakpur (Fig. 4). The conservation laws, on which both classical and quantum physics are based are an outcome of the symmetry principle. This has also been very effectively used to understand behaviour of elementary particles by Gell-Mann and others. Elements (Mendeleeve's Table) are arranged in eight fold symmetry. These 118 elements can be arranged in the form of octets, their properties repeat after every eighth member. and so are the elementary particles. In fact, symmetry principle has been used as very powerful tool to predict the existence of many unknown particles by Murray Gell-Mann, another Nobel Laureate and a profound thinker. He arranged the elementary particles in "eightfold way" and was eventually able to predict and discover quarks, the smallest constituents of matter known to day. It is known now that elementary particles (called hadrons) can be organized in octets (8) and decuplets (10) whereas leptons in nonets (9). The universe itself is known to be formed by super-symmetry. Sometimes a symmetry is also violated like parity is a mirror symmetry which is found to be violated in certain reactions. Thus existence of symmetry and its violation, both are of fundamental importance in understanding the nature of the basic processes governing the behaviour of fundamental particles.

Exclusion PrincipleApplicable mainly to the micro world, the Heisenbergs Uncertainty principle states that it is impossible to completely quantify all the parameters describing the state of a particle precisely. If measurement of some physical quantity is made, then according to quantum physics, the state of the particle is deemed to have changed instantly into a different state. It is not because one cannot measure the parameters accurately because of limitations of the instruments or their precision but that the measurement cannot be made without changing the state of the particle. For example, both the parameters in the pairs of energy (E) and time (t), or position (x) and momentum (p) can only be known within some uncertainty ∆ (∆E∆t=h; (∆p∆x=h), defined by the Planck's constant h, which has a very small, but none the less, finite value. Uncertainty principle is one of the most fundamental principles applicable to the realm of all the physical microworld.

This indeterminacy may also be the root cause of Syadvada, another Jain concept. Syādvād, a corollary of Anekantvad, is also considered as a cornerstone of Jain philosophy. It has been translated as "perhaps", or "May be" which appears to me as very qualitative (or crude) definition.

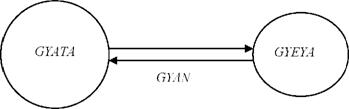

In a larger perspective, the uncertainty principle offers a choice, though limited, in behaviour of nature. In the domain of biology, such uncertainty can allow evolutionary changes. The uncertainty in energy levels, e.g., provide a scope for a variance in chemical reactions, leading to different products and thus bring about evolutionary changes. The Jain philosophy recognizes only three entities in the universe, the Gyata (knower), Gyeya (the object to be known) and the Gyan (knowledge) (Fig. 5).

The transfer of knowledge from the object to the knower changes both the object and the knower. This is precisely what happens according to the uncertainty principle so that with every measurement, the object changes and it is not possible to determine its state completely, which may require several measurements.

The Principle, first enunciated by Pauli states that two elementary particles in the same" state" cannot exist together. Nobody can state it better or more rigorously or elegantly than Kabir, when he, after he gained enlightenment said" When I am there, God is not there and when God is there I don't exist, because the space is too narrow to accommodate both of us (being in the same state).

Having pointed out that the laws which operate upon the gross universe and the micro universe are different, we revert to the two propositions made at the beginning of this article to define Anekantvad.

The first proposition is easy to prove even by simple logic. If the universe is without a beginning, then when did the vast diversity, we see today in the multifaceted universe, begin, if everything originated from "one". If diversification started from the very beginning then, it could not be "one" but already "many" to start with. If diversification began at some later time, then the "one" survived without diversifying for some finite time. What then caused it to diversify at that particular point of time? According to causality, it cannot by itself, without a cause, multiply so there has to be a causative agent to bring about the diversification. This argument thus negates "one" being responsible for the diversity of the universe.

Even "one" cannot exist by itself. That has given rise to the well-known Mach's principle in physics. We may recall here that Mach's principle deals with the concept of origin of inertial mass. Broadly speaking Mach's principle states that the inertial mass of a body is solely due to interaction of other bodies in the universe. Heller (1975) mentions it in the following way: " The local inertial frames are entirely determined by the distribution and motion of all matter present in the universe" and Einstein formulated it as "the entire inertia of a point mass is the effect of the presence of all other masses, deriving from a kind of interaction from the latter" There is yet no "proof" for this principle but Einstein is said to have derived much inspiration from the Mach's principle for development of his Theory of Relativity.

The implication is that inertial mass cannot exist in isolation. Now we may ask if this principle can be extended to other physical entities or even spiritual entities. Are we living in a totally interactive world and everything here is interactive. The same may be postulated for life (jiva) or consciousness. Life certainly cannot exist in isolation. If all living species, except one, in the universe or even on Earth vanish, the last one also will not be able to survive. Therefore the life is a result of interdependence (or interaction) with other living species. The principle of non-violence immediately follows since the whole becomes a cause for the existence of a part of it and both are indistinguishable. In effect, when, one does any harm or kills some body, howsoever primitive, one is killing a part of one self, because his very existence is interactive in nature. It is like committing a small suicide.. Thus the inertial mass, which is a physical entity and the consciousness, which is a spiritual attribute, are both interactive in nature and their origin is a consequence of interaction. We will return to this argument at the end when we discuss entanglement.

To discuss the second proposition, we now discuss the laws applicable to the micro world within the framework of the quantum mechanics.

Quantum Mechanics

The quantum mechanics puts severe constraints on certainty of our knowledge. Two tenets of quantum mechanics that are relevant here can be crudely described as follows. One is that the universe does not exist if you don't observe it, equivalent to the paradox of the Schrodinger's cat (see e.g. Gribbin, 1993). This implies that universe and the observer exist as pairs and neither can exist without the other. The other concept is that a particle behaves in different ways at different times. This is clear from the famous two-slit experiment which is the backbone of quantum mechanics and particle-wave duality. Anekāntvād not only explains seemingly contradictory propositions in daily life, philosophy, macro world, mental exercises and in spiritual domain, it also brought in the concept of Avyaktā or inexpressibility of certain states. Questions which cannot be answered in affirmative or negative, like the existence of soul, could be dealt with in the framework of Anekāntvād. It is, it is not; it is and yet it is not, it cannot be expressed and so on. This concept is common to Quantum behaviour, which cannot always be expressed in language. Anekāntvād is not simply a multi-view perception theory. It is not a limitation of consciousness that it has limited capability of perception of the physical world. Thus it is not the consequence of not being able to look at an object from different perspectives but that the object cannot be known from all the perspectives. Anekāntvād is as fundamental as the uncertainty principle, which states that some properties cannot be measured accurately, not because of instrumental limitations but because of inherent behaviour of nature.

Thus, in the physical world, as in philosophy, things or ideas have plurality of attributes and these can be apparently contradictory or conflicting. Anekāntvād successfully harmonises or accommodates such views and completes the description of physical reality. But when we talk of manyfoldedness, the question obviously arises, how many. Certainly more than one, but can it be infinite? Saptbhangi or sevenfoldedness is a corollary of Anekantvad. This has been very clearly explained by D.S. Kothari in his essay on" Complementarity principle and Eastern philosophy". According to the principle of Saptabhangi reality can be described in seven ways i.e. it exists, it does not exist, it exists and yet it does not exist, indeterminable, its existence is indeterminable, its non-existence is indeterminable and its existence as well as non-existence is indeterminable or inexpressible. Saptabhangi has been explained very succinctly by Kothari in a quantum mechanical way by taking the example of a particle in a box which is divided by a partition with a hole into two compartments. Because of the particle-wave duality, the particle can be in compartment A, or in compartment B, In A and still not in A, In B and still not in B, not in A and B, in A as well as in B and in an indeterminate state (avyakta).The same solutions emerge from the considerations of quantum mechanics as has been shown mathematically by taking wave functions.

Quantum numbers

Besides, the normal properties like mass, electrical charge, motion etc. the elementary particles have several other attributes which are denoted by Quantum numbers. These quantum numbers do not change continuously but in multiples of simple numbers like 1 or 1/2, a concept of the quantum theory. Since we are venturing into the unknown territory of physics, names have been given at the fancy of the discoverer and should not be interpreted in terms of its literal meaning. Thus spin may not mean spin in the ordinary sense and there are quantum numbers like isospin, and positional (e.g. orbital) quantum numbers. Quarks, leptons and gluons are currently considered to be the basic building blocks out of which all the matter of the physical world is made. Protons, electrons and neutrons are now thought of as being built from six quarks and six leptons. The current particle models due to Gell-Mann and others indicate three generations of quarks and leptons. Leptons include electron like particles, sometimes called mesons and the associated mass-less neutrinos.

First generation

Quarks: down and up quarks

Leptons: electron and its neutrino (ve)Second generation

Quarks: strange and charm quarks

Leptons: mu meson (µ) and its neutrino (vµ)Third generation

Quarks: bottom and top quarks

Leptons: Tau (τ) and its neutrino(vτ).These quarks come in three colours (red, blue and yellow) making them 18 in all. The 18 quarks and the six leptons (and their antiparticles) sum up to 48. Gluons act as their carriers and there are eight of them. To this when we add the carriers of electromagnetic force ie photons, W± bosons and Z0, the total goes to 60. These sixty particles make the whole Universe. To this may be added graviton, the carrier of gravitational field.

The six types of quarks are named as up, down, top, bottom, strange and charm. But "up" does not mean up in the colloquial sense, nor "bottom" means bottom but they are just names. All the names mean is that they are different from each other. Likewise they have been given quantum numbers called colour and flavour, which have nothing to do with their literal meaning. Colour actually means a type of force and flavour means another attribute. So when we say a quark has a colour (usually red, yellow or blue) it simply means they experience a kind of force, called the "strong" force but are different, ie have different attributes. Similarly gluons do have flavour and different attributes. What these attributes are in the context of common sense is debatable or rather inexpressible. The lesson, in context of Anekantvad is that as we go to finer constituents of matter, new attributes come into play and the number of attributes increase. The concept that there would be one fundamental particle in nature which has given rise to the visible universe is erroneous and is the crux of Anekantvad.

Now let me ask my question in another way! If I hold "a" particular perspective of a thing or "concept", is it a limitation of my consciousness or it is the way the object reveals itself. I take the premise that the consciousness has no limitation of comprehension and is capable of conceiving many or all the perspectives at once. It is the object which exhibits different perspectives at different times, in different contexts. In other words multiple-perspectives is the inherent quality of an object of the physical world. Thus Anekāntvād is not simply a multi-view perception theory but enables us to understand the true nature of reality. It is not a limitation of consciousness that it has limited capability of perception of the physical world. It is not looking at an object from different perspectives but that the object itself exhibits multiple perspectives which cannot all be known at the same time to describe its "state" completely. Thus, in the physical realm, Anekāntvād is as fundamental as the Uncertainty principle, which states that some properties cannot be measured accurately, not because of inherent nature of the behaviour in the micro world.

Separately, the various quantum numbers may describe only a part of the reality, but taken together they described the whole. In the micro world, we encounter two other phenomena which have some relevance in the present discussion: confinement and entanglement. The property of "confinement" of quarks in the quark-gluon plasma has been observed. Simply stated, quarks cannot be isolated as free particles. It will only be speculative to think of what other attributes will be observed as one goes to further finer and finer constituents of matter, of quarks, if there are any. Entanglement implies that all the particles in the universe behave in an inter-related manner, Briefly stated, when two systems, of which we know the states, enter into temporary physical interaction due to known forces between them, and after a time of mutual influence, the system separate again, then they no longer be described in the same way as before. By interaction, we may say the quantum states have become entangled. All the particles in the Universe interacted together at the time of Big Bang and therefore they are all entangled.

Basic Forces of Nature

At this point of discussion it may be useful to briefly enumerate various forces of nature which affect these particles. Is everything controlled by one kind of force, which manifests in different ways at different energies or there are many kinds of basic forces. Long time ago electric and magnetic forces were considered to be different till Maxwell, way back in 1863, showed that they are one and the same, now called the electromagnetic force. They control the behaviour of charged particles. Then there is gravitation which is the weakest of all, but binds all the matter in the universe together. For understanding behaviour of elementary particles we need two nuclear forces, the weak (responsible for reactions where neutrinos are involved) and the strong (which binds the quarks and nucleons in an atom together). Recently Weinberg and Salam showed that the weak force is the same as electromagnetic force at high energy (temperature > 1029 K) and only at lower temperature they appear to be different. For this synthesis they got a Nobel Prize. Thus we say that electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces have been unified into electroweak force. Thus, as of now, we are left with three basic forces of nature: gravitation, strong nuclear force and electroweak. It would be satisfying and simpler if all these three forces are a manifestation of "one" single force and therefore attempts have been made to unify them in a Grand unification theory (GUT) or theory of everything (TOE). Lot of efforts are being made to unify these various forces of nature. The greatest unification of all times was done by Einstein who showed that mass and energy is the same thing and gave his famous formula E= mc2. Whether there is only one ultimate force of nature or there are many, remains to be ascertained by further research but as of now it is difficult to reconcile the three forces into one, again consistent with Anekantvad.

We thus see that by properly amalgamating Jain concepts with concepts of modern physics, it should be possible to ascertain the true nature of reality and make further predictions. Anekantvad can be applied to test many predictions of modern science and may have a role to play in making a correct choice between different possibilities.

Concluding remarks

Thus we have seen that according to Anekantvad, one cannot give rise to many but many can combine to give rise to one. The question naturally arises that these "many" must comprise of many individual "ones". According to simple logic then, "one" must be the basic constituent of the physical world. This is not true. At the ultra-micro level, one and many are indistinguishable. If it defies logic, let it, but such is the nature of reality. This in essence is Anekantavad. We may try to understand this in the following way. Anything is perceived by its attributes and therefore "one" which has many attributes is actually "many".

In this article we have made an attempt to see if Anekantavad can be treated as a physical law. To establish it, we have to first define it more rigorously and possibly quantitatively, make predictions and experimentally test them. It is for this reason that we have pointed out above at various places whether some scientific concepts are consistent or inconsistent with Anekantavad. If Anekantavad can be treated as a physical principle, as profound as the principle of symmetry or complementarity, it will help us understand the nature better. This has been the motivation for writing this article. To pursue it further will require more clarity and efforts.

Before we end this discussion, it is pertinent to ask "what benefit will accrue by seeing a common ground between Anekantavad and Quantum mechanics. Anekantavad thus becomes a testable hypothesis. Beyond academics and the pursuit of truth, it has a vital role to play in society which must be explicitly stated. Firstly if the religious principles are based on physics then the intra-religion contradictions can be dispensed with. Everyone believes in physical laws because they are experienced in daily life. So since complementarity is an accepted principle of modern physics, Anekantvad also get scientific validity. One may say that this is not needed, but I beg to differ. Secondly, in the modern age we must be able to view, test and verify religious concepts from the point of view of science. So that if religious principles have a basis in the well-established physical laws then there is no need to compartmentalize various religions. The apparent contradictions between various religions and religion and science may be simply due to different emphasis on different aspects of physical laws. When they are complete or integrated, they will probably all become the same and bring about a universal harmony of thought and action.

References:

- Close F. The Cosmic Onion, Heinmann Educational

- Goldstein, S., Lebowitz, J.L., Quantum mechanics in The Physical review: The first 100 years (H. Henristroke, eds).

- Gribbin John (1993) In search of Schrodinger's cat, Corgi Books.

- Kothari D.S. The Complementarity Principle and Eastern philosophy, Niels Bohr Centenary volume (A.P. French and P.J. Kennedy, eds) Harvard University Press, Cambridge, USA 1985, 325-331.

- Matilal B.K. The Central Philosophy of Jainism (Anekāntavāda) L.D. Series 79, (D.

- Malvania and N.J.Shah (Gen. Eds) L.D. Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad.

- Mookerjee, S.,The Jaina Philosophy of Non-Absolutism 1944, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

- Padamarajiah Y.J., A Comparative study of the Jaina Theory of Reality and Knowledge,1963, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

Figures & Captions:

Fig. 1.

Macro to the micro universe showing the sequence from the gross to the subtle components of nature. Sixty Elementary Particles (Quarks, Leptons and the Force carriers, together with their antiparticles), known to be the building blocks of matter are arranged in the box according to their attributes.

Fig.2.

The two slit experiment showing that photons (or electrons) act as particles when they are observed by particle detectors (D), giving the characteristic spots on the photographic plate (above). and waves when they go unobserved (below) giving rise to the well known interference pattern due to waves.

Fig. 3.

The Chinese concept of Yin and Yang: indicating that opposites are complementary (Contraria Sunt Complementa), used by Niels Bohr as coat of arms for the quantum physics to explain the complementarity principle.

Fig. 4.

Evolutionary symmetry: A sculpture from the Ranakpur Jain Temple (ca 11th century).This exquisite Fractal representation of the idea that a part of nature contains the full beauty, elegance and complexity of the whole.

Fig.5.

The interaction between knower (Gyata), object (Gyeya) via knowledge (Gyan) indicating that an observation affects both the knower and the object, making it impossible to know their "state" completely by any observation.

Prof. Dr. Narendra Bhandari

Prof. Dr. Narendra Bhandari