Among Art Historians the complex of Jain temples at Deogarh is connected with the work of the German scholar in Jainology and Indian Art History Prof. Klaus Bruhn, who stayed at Deogarh in the 1950's for a long time and wrote a monograph on the Jina Images of Deogarh as the result of his explorations and studies. The following essay is a revised and abridged edition of a summary of his researches which has been published in a book by Klaus Titze, titled Jainism. A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence (Delhi 1998, pp. 100-118).

Jain Temples at Deogarh

Jaina art begins at Mathura shortly before and under the Kushana dynasty at c. 100-250. If we make some allowance for a period of limited activity, we can say that a new phase started under the imperial Gupta dynasty of Northern and Central India (320 to c. 500). The centre of Jaina art was still Mathura, but in the subsequent periods the activities of the Jainas spread to other places as well. In spite of continuing artistic activities, Jaina art in Central India regained its former importance only at a somewhat later date with Gwalior and Deogarh becoming centres of Jaina art (Gwalior: 700-800, Deogarh: 850-1150). The two places represent a new phase which is, on the whole, typical of Central India and which can be called a regional style. Before considering the sculptural art of Gwalior and Deogarh, we will say a few words about the general topographical and historical situation. […]

Deogarh is a small village which can be reached by a metal-road from Lalitpur. The village is situated in the low-lying lands (“Valley”) at the foot of the Fort-hill on the right bank of the River Betwa. The ancient monuments are found partly on the Hill, within the circumference of the old Fort-wall, and partly in the Valley and near the village. Generally, the Hill does not stand out sharply from the surrounding area, but on its southern side it is cut by the River Betwa, a tributary to the Yamuna and the Vetravati of Sanskrit literature.

"Flowing for the most part in a rocky bed, the Betwa forms a series of deep pools and picturesque cataracts. 'The narrow gorge where it forces its way through the Vindhyan hills and the magnificent sweep it makes below the steep sandstone cliff which is surmounted by the Fort of Deogarh is a scene of striking beauty'."

Deogarh is known both for the Gupta Temple (500-550) near the village and for the group of Jaina temples in the eastern part of the Fort (850-1150). The Fort is overgrown with jungle which had not been completely removed from the Jaina monuments before the visit of D.R. Sahni of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1917/1918. There are also various other monuments in the Deogarh area, most prominent being the dilapidated Varaha Temple on the Fort (700-800) and the sculptures (mother goddesses and other Hindu idols) cut into the cliff-wall along the three ghatis or flights of steps leading from the Fort down to the River Betwa (550-700). The Gupta Temple with its rich sculptural decoration is one of the great Hindu monuments of the Gupta period, and the sculptures (mostly images) of the Jaina compound (850-1150) are important on account of their stylistic and iconographic variety. The sheer number of images is impressive; not all of them, but more than four hundred can be labelled as 'deserving description'. The material of the Deogarh monuments is sandstone, often of a warm brick-red colour.

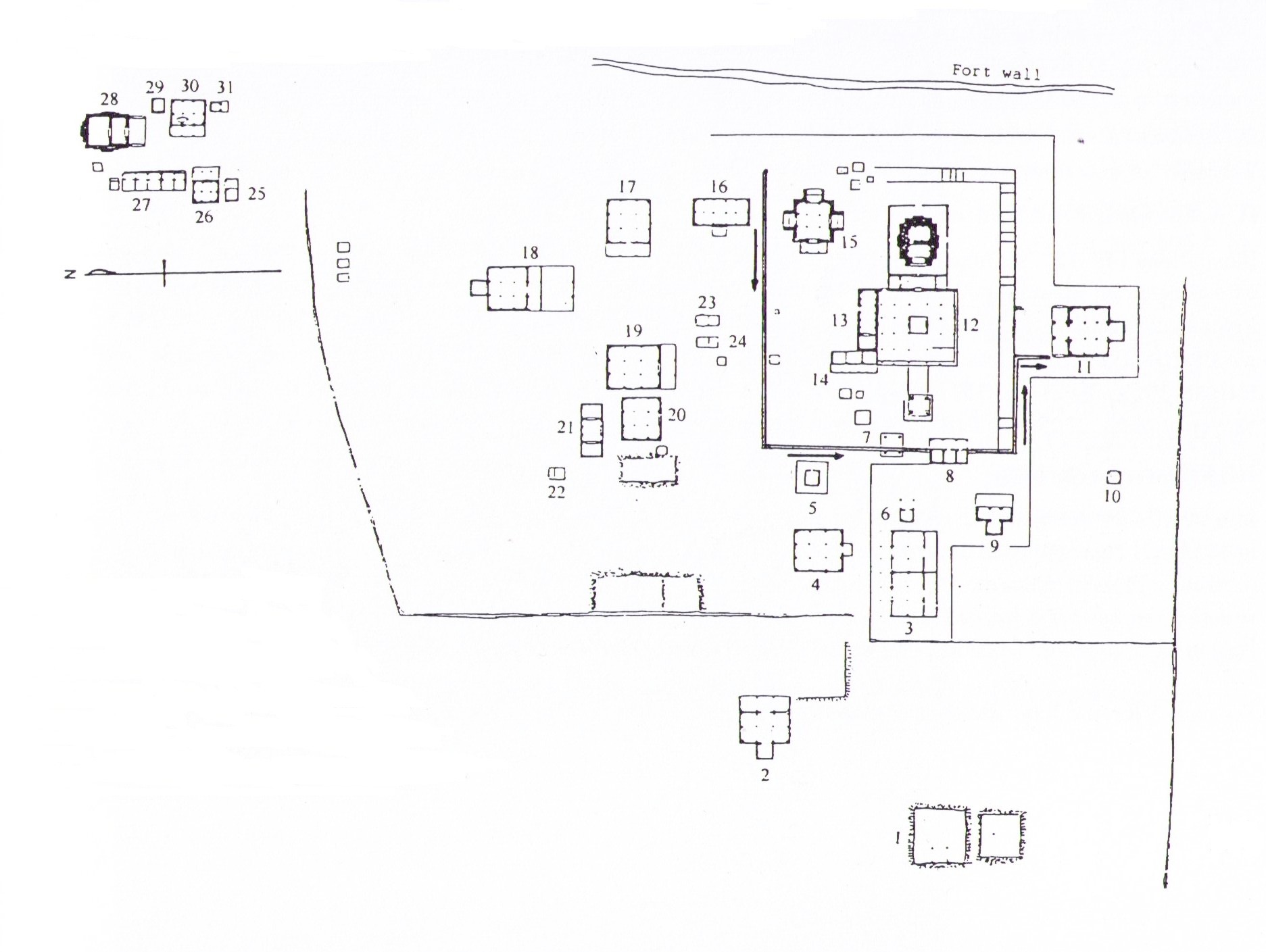

Fig. 1: P.C. Mukherji's plan of the Jaina temples of Deogarh (1887/88). The drawing is not always accurate, but it gives a good idea of the site as it existed in the eighteen-eightees.

The name 'Deogarh' is of little consequence. There are many places named 'Deogarh' ('fort of the gods'). Fortifications which encompass temples are certainly not rare, and 'Deogarh' may thus have become a popular designation for villages in the vicinity of temples within fort-walls. Furthermore, the present village is a settlement without history. In 1811, the Fort was wrested by a Colonel Baptiste from the Bundela Rajputs as we read in the Imperial Gazetteer of 1908. To date, nobody has tried to reconstruct the local history from the edited inscriptions recovered from the Hill or the Valley, and we do not know whether it will ever be possible to transform the scattered epigraphical evidence into a coherent account of the site. No doubt, we can date most of the remains on stylistic and palaeographical grounds, but these datings do not solve all the problems connected with the locality. We know the history of the dynasties ruling over this area, but we do not know what role the Fort-hill and the surrounding territory played in the wider political developments. We also do not know how far the ruling dynasties encouraged building activities in a particular area. The construction of the Jaina temples of Deogarh was at any rate an internal affair of the Jaina community as a merchant community.

The richness of the extant material and the clouded history of the locality call for an intensified evaluation of the available data and for the collection of new data. The debris of Hindu and Jaina monuments is promising material for the art historian, those Hindu and Jaina inscriptions which are still unpublished (some important and some not) can be properly edited, and trial trenches can be made, both on the hill and in the adjacent Valley. Such trenches might bring to light foundations of lost Hindu or Jaina temples to which a good number of the exposed sculptural fragments must be traced back. Further fragments below or even on the surface could be secured by adequate exploration of promising localities. Whether studies on these lines will produce a consolidated historical account we know not, but it is certain that they will give us a more complete and hence a more satisfactory idea of the site than we have today. 'Deogarh' is certainly more than the sum of its published monuments.

Fig. 2: The Jaina temples of Deogarh before restoration and modernization. Photograph of the Archaeological Survey of India (1918).

The Jaina temples (thirty-one according to D.R. Sahni's counting) differ in character, size, and age; some have considerable architectural merit, while others are basically shelters for the accommodation of images. The temples and images belong to two distinct periods, which we call 'early-medieval' (850-950) and 'medieval' (950-1150) respectively. The buildings and the images have suffered considerably under the devastation of the Islamic iconoclasts as well as under the effects of vegetation and temporary neglect, but there must also have been intervening schemes of reconstruction (jirnoddhar as the Jainas say). All the details are unknown. Moreover, the building of the Fort (in 1097, or earlier, under the name of Kirtigiridurga) must have been an event of considerable importance that affected the life of the Jaina community and the management of the temples to a large extent. The responsible Jaina community lived perhaps at some distance from the group of temples, as is the case today, but Hindu settlements must have been in the vicinity.

The Imperial Gazetteer records that 'Jains occasionally still worship there'. After 1930, when the Jaina temples were placed under the jurisdiction of the local Jaina committee, modern restoration work started. In the beginning, the emphasis was on preservation, circumspect reconstruction, and general maintenance of the temple group. There were hardly any changes made in the archaeological substance, although the construction of the Great Wall implied that the sculptures were set in mortar. This wall was built in those days in order to accommodate the majority of the vast number of sculptures lying in the Jaina compound in the open air. When all the absolutely necessary work had been completed, new activities started (in the sixties), and the idea of preservation ceased to be the sole consideration. The place had to be made attractive for pilgrims and other visitors alike. Besides, protective measurements became necessary. In 1959, art robbers had looted the temples, cutting off and pocketing the heads of many Jina figures. We are told that the miscreants were caught, but actually no accurate information is available about the culprits and the whereabouts of the booty. Subsequently the Temple Committee of the Jainas have taken various steps to ensure a better protection of the sculptures. They have also changed the general character of the site in so far as the Jaina temples are no longer lonely monuments in the jungle but rather elements of a comfortable park-like area which betrays a philosophy of improvement. However, in some cases, sculptures and minor structures have been treated in a way which makes the study of old photographs necessary for the art-historian. This would speak for future co-operation of the responsible bodies with experts whenever extensive work is undertaken in connection with religious sites. Likewise, the management guidelines for the UNESCO's World Cultural Heritage Sites might be taken into consideration. […]

Fig. 3: Deogarh 1994; The 'portico' of Temple No. 12 and the central area of the Jaina compound (Photo by Kurt Titze).

Jaina images at Deogarh

The Jaina temples of Deogarh boast of a great number of images, virtually the greatest concentration of Jaina images in the whole of India. Apart from the basic difference between 'early-medieval' and 'medieval', we notice various shadings of style, including rather pronounced differences in the physiognomy of the different Jina figures. In addition to the Jina images we find numerous images of Jaina divinities, and there are also images of Jaina monks. Miniatures figures of various divinities embellish the numerous pillars found in the temple compound. The great number of images is not the result of any concentrated scheme, but due to donations made over the centuries by pious Jainas, some rich and some without adequate means. This also explains the fact that some of the images show little artistic merit. Below we will mainly describe three first rate Jina images, belonging to Temples Nos. 12, 15, and 21 (see Fig. 1: plan of the temples of Deogarh) respectively. The first two images demonstrate the art of the early-medieval period, while the third belongs to the medieval period.

The first image is the great Shantinatha in Temple No. 12. Built before 862, this temple consists of a quadrangular structure which is crowned by a tall shikhara (tower). The quadrangular structure comprises the sanctum and a circumambulatory passage. Some time before 1350, a large pillared hall was built in front of the temple, and at a still later date (we do not know when) a 'portico' was prefixed to the pillared hall. (See Fig. 2 and 3, for Temple No. 12 and its extensions, and Fig. 4 and 5 for the Shantinatha image.) Temple No. 12 has but few Jina figures on its outer walls. Contrary to Hindu temples, where the figures on the outer walls leave no doubt as to the Hindu character of the building, Jaina temples have a 'neutral' exterior. There may be wall figures of every provenance, but they are rarely clearly Hindu and rarely clearly Jaina. Jina figures in particular are inconspicuous or missing altogether. As a consequence, the Jaina character of a monument may be recognizable, but it is never obtrusive - this was the price to be paid for the easily granted permission to erect Jaina temples under Hindu rulers. Moreover, there were no restrictions as far as the interior is concerned. In fact, the circumabulatory passage of Temple No. 12 is jammed with colossal Jina images, and the sanctum (sanctum plus vestibule) houses, besides the great Shantinatha image, four standing images of the Jaina goddess Ambika.

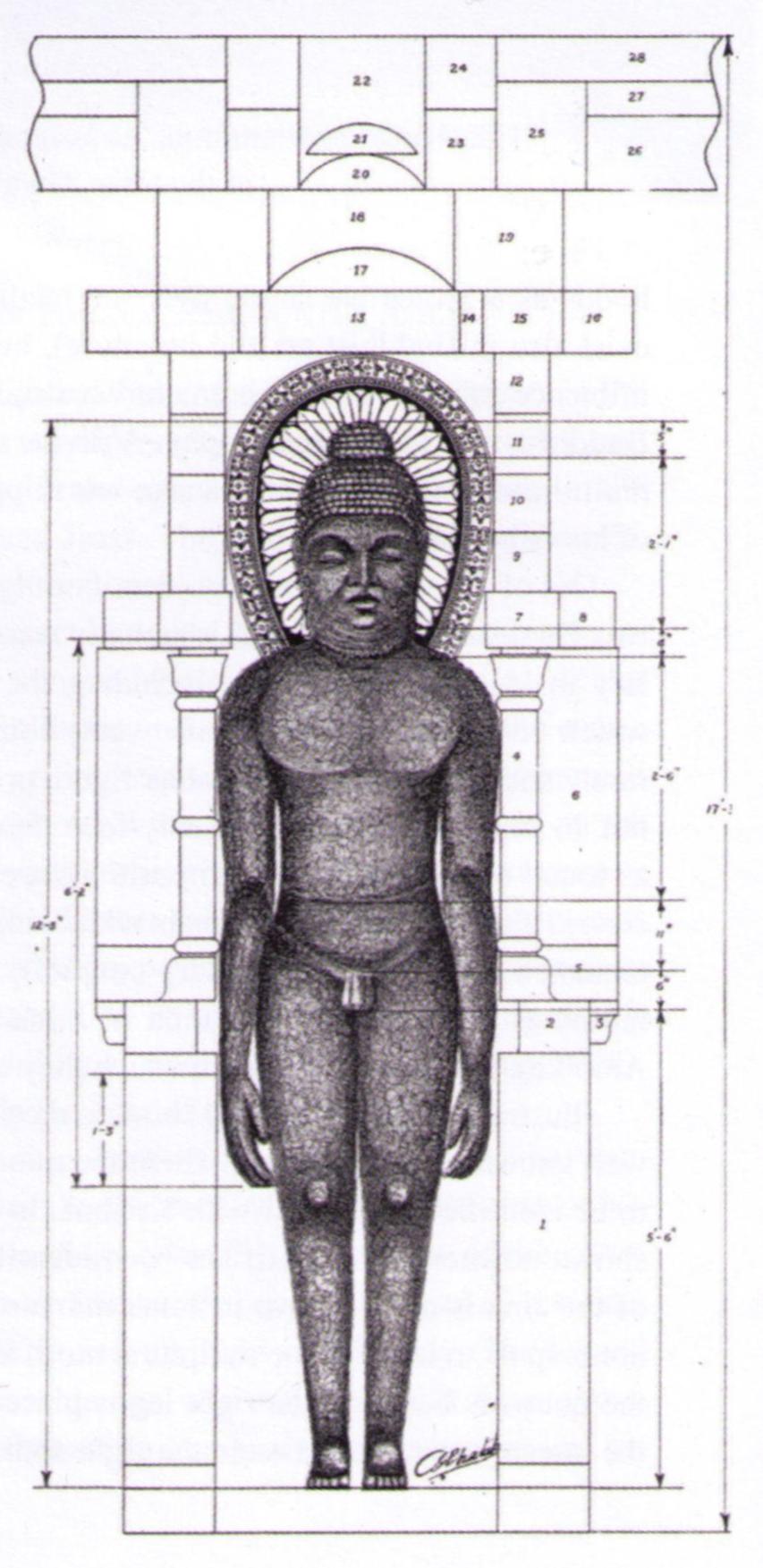

Fig. 4: The great Shantinatha (height of the figure 3.73 m) in Temple No. 12 at Deogarh; organisation of the image.

If we allot the elements which surround the great Shantinatha to three vertical zones, we can 'read' the upper portion without difficulty. The vertical zone to the left has, from top to bottom, a male garland-bearer, a rosette, two leaves (= Ashoka tree), an elephant with small figures, a garland-bearing couple, four figures standing for 'planets' (numbers one to four), and the capital of a pillar (see Fig. 5). The central vertical zone has, from top to bottom, a drummer (hardly visible in our photograph), two parasol roofs, a vegetable composition, a single parasol roof, another vegetable composition, and the great halo. The vertical zone to the right is identical with the zone to the left, but the 'planets' are numbers five to nine, the remaining members of a standard series of nine astral divinities. The miracle group is thus clearly represented with the fly-whisk bearers appearing further down in their appropriate fields (marked as '1' in Fig. 4). The set of 'eight' miracles has been amplified by a few additional motifs (rosette etc.), the result being a composition of considerable complexity. There is a marked emphasis on the 'inward' movement of the accessory figures (hovering genii, elephants, fly-whisk bearers), creating the impression that 'gods and men flock together to worship the Jina'. The identity of the Jina (Shantinatha) is not indicated on the image and follows only from a pillar inscription outside the temple. In order to appreciate the impression conveyed to the visitor of the sanctum, one has to consider the size of the Jina composition (5.20 metres) and the semi-darkness of the room with its bare windowless walls. The facial expression of Shantinatha is stern and reserved. Impressive as the great figure is, some visitors will prefer the style of the two flanking fly-whisk bearers and of the four Ambikas - a faint echo of the Gupta age - to the severe expression of the Jina.

The Jina image of Fig. 6 is housed in the narrow sanctum of Temple No.15 (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 1: plan of the temples of Deogarh). The composition combines general aesthetic perfection with a convincing rendering of the theme of meditation. The Indian art-historian Krishna Deva observes: “The main image of this temple, a masterpiece of early medieval art, represents a seated figure of Jina, radiating spiritual bliss and effulgence and recalling in its sensitive modelling and serene expression the famous Gupta image of Buddha from Sarnath.” In our description we concentrate on the image shown in the illustration but we ignore the superimposed register, which is not visible in our illustration. This unconventional element repeats basically the motifs (standard motifs) of the top area as seen in Fig. 6 (garland-bearers etc.). The portrayed Jina has no cognizance, and, contrary to the Shantinatha of Temple No. 12, external clues are likewise missing. One wonders what a temple with an unidentified main-idol was called by the worshippers. The motif of the lion-throne is amplified by the addition of a cushion and two blankets. Well-carved figures of Ambika and Kubera are seen to the left and to the right of the throne. A Jina triad en miniature appears above each of the two attendant deities. Whereas the two previous Jina images were to some extent construed in an additive manner, we see in this case an integrated whole where each part contributes to the general effect of the composition. This, is best demonstrated by the motifs above the head of the Jina (parasol roofs etc.) which are arranged so as to form a self-contained ensemble. The carving of the composition is delicate, and some decorated surfaces such as the halo with its flower design must be viewed up close to be properly appreciated. Unfortunately, this image is among the pieces which have been altered in the course of the more recent operations. A cognizance (an antelope in this case) has been incised into the lower blanket, and the Jina figure (including the halo) has been darkened so as to make it stand out more clearly against the pale backslab. Since the medieval period we notice in Northern India the tendency of providing the Jina figures more or less regulary with cognizances, but the incision of cognizances in existing (anonymous) images has never been practised in the past.

Fig. 5: The great Shantinatha (Photo by Raymond Burnier).

Temple No. 15 has merely a flat roof, but is a solid and well-planned building. By contrast, the small Temple No.21 (see Fig. 1: plan of the temples of Deogarh), which houses our next image (Fig. 7), is one of those simple Jaina buildings (found at Deogarh and elsewhere) which were only constructed as shelters for Jina images and which cannot claim any artistic merit. An inscription on the 'foot-band' below the lion-throne tells us that a certain monk (or scholar) Gunanandin caused the image of Chandraprabha to be set up. Chandraprabha's symbol, the crescent, is shown in the middle of the tracery course which appears below the 'foot-band'. The trend to attribute separate identity to all the different Jinas is now fully developed, the vehicles of identification being in the first place inscriptions and cognizances (symbols). Moreover, Kubera and Ambika, frequent attendant deities between c. 650-950, are now replaced by other divinities. The basic idea is to provide the 24 different Jinas with 24 + 24 different attendant deities, a commendable theoretical scheme which represented the new trend, but was rarely if ever translated by the artists into practice. In contrast to the elephants at the top which have some legendary background, the elephants on which the fly-whisk bearers stand are a purely decorative addition which enriches the new scheme. Stylistically, the Chandraprabha in No.21 is comparatively close to the image in Temple No. 15. However, medieval images clearly differ from early-medieval ones, even in those cases where the latter already seem to show the way to the new period. We notice in the case of the Chandraprabha image deep undercutting where the projecting portions create an element of depth which is in contrast with the comparative flatness of the earlier compositions. We also notice an upward movement, a new lightness, in contrast to the earlier images where the figures are, on the whole, firmly planted on the ground. Of course, the 'shyness' of the old fly-whisk bearers is gone, and the figures now seem to stare into the viewer's face. The aesthetic sentiment has changed. It can be added that many medieval sculptures at Deogarh are dated and can even be used to date pieces at other places. The Chandraprabha image is preserved only through our photograph. In 1957 the image was still intact, although slight damage had occurred here and there, but “Now the image is but a ruin of what it was: the main figure and a number of subsidiary figures have lost their heads.” The art-robbers, who ransacked only the medieval images, had brought havoc to one of the most exquisite Jina images of that period.

Fig. 6: Unnamed Jina in Deogarh Temple No. 15 - "a masterpiece of early medieval art" (Photo courtesy American Institute of Indian Studies, Ramnagar).

The images shown in Fig. 8 (four tutelary couples and one Ambika) demonstrate at a glance to what extent the Deogarh images differ both in their subject matter and in their aesthetic value. We see five tolerably preserved images of average quality which are fixed to the Great Wall. This wall (Fig. 3) surrounds an incomplete square, including Temples Nos. 12 and 15, which has thus become the central area of the Jaina compound. The images and fragments which are fixed with cement to this wall form an omnium gatherum of Jaina sculptures, including, of course, three or four very old pieces. One wonders where these sculptures had originally been arranged. The image occupying the lower left of Fig. 8 (one of the four tutelary couples) is medieval and excels in 'linear discipline', while the other four images of this illustration are early-medieval and recall a more gracious tradition. However, the five images are not very original from the point of view of style and iconography.

The tutelary couple of Jaina art as we can study it in Fig. 8 is always seated below a tree. A child is shown either on the lap of the female figure alone, or on the lap of both, the female and the male figure. A frieze with a series of figures appears below the couple. This iconographic type is not mentioned anywhere in Jaina literature and has been imported into Indian art from Western Asia in the early centuries of the Christian era. At Deogarh the Jaina goddess Ambika is always shown under a mango tree, either standing or seated. In Fig. 8, the goddess is standing, as are the four Ambikas in the sanctum of Temple No. 12. The missing upper portion of the slab contained the mango tree.

There are quite a few images, many fragmentary, but almost all of good quality, which have not been fixed to the Great Wall, but lie in the open air, or in such places as the pillared hall before Temple No. 12. Finally, we have to mention a collection of small-sized and unimpressive Jina images housed in a shelter in the said pillared hall. This room has been created by the construction of plain walls between the four central pillars of the hall (see Fig. 1: plan of the temples of Deogarh).

Fig. 7: The Jina Chandraprabha in Deogarh Temple No.21. "Now the image is but a ruin of what it was..."

Jaina temples at Deogarh

We will conclude the discussion of Deogarh with a look at the central area of the Jaina compound (Figs. 10, 9, and 1:plan of the temples of Deogarh). Fig. 2, one of the invaluable and rarely published old photographs of the Archaeological Survey of India, shows primarily the complex of Temple No. 12 - shikhara temple, pillared hall (vertical arrow), and portico (diagonal arrow), all in axial alignment and viewed from WNW. The other temples are Nos. 7 (horizontal arrow), 14, 13 (13 behind 14, only the roof visible), 15, 16, 23 (23 = upper diagonal arrow), and 24 (lower diagonal arrow). The site is shown here after jungle clearing but before the execution of preservation measures. The Great Wall as it exists today passes between No. 7 and the portico of No. 12 (wall section running from north to south) and again between Nos. 15 and 16 (section running from east to west). The photograph was taken in 1917/18 during D.R. Sahni's campaign and must be consulted in combination with a still earlier plan which was drafted in 1887/88 and where we have marked in our reproduction (Fig. 1: plan of the temples of Deogarh) the position of the Great Wall (four arrows). The photograph also shows how the comparative monotony of the Jaina group was relieved in Rajput times by the construction of numerous pavilions. Pavilions crown most of the flat-roofed temples, including Nos. 15 and 16. In the foreground we notice No. 7, a pavilion which stands on the ground and forms an independent architectural unit.

Fig. 3 (1994) shows above all the portico of No.12, which is here seen from SSW. This portico was assembled at an unknown date from re-used parts. The two front pillars are medieval and display on all sides exquisite carvings. Of the two pillars in the rear (both early-medieval), the one to the right bears an inscription which says that it (the pillar) was erected in 862 near the temple of Shantinatha (No. 12). We thus know that No. 12 was built before 862, and we also know that its main idol represents the Jina Shantinatha. In the photograph, we recognize the pillared hall before Temple No. 12 (from SW), Temple No. 14 (also from SW), and above the Great Wall the roof of Temple No. 19 with its pavilion. Due to the modern roof which was built after the nineteen-fifties and which rests on its inner side on plain pillars, the visible side of the Great Wall lies in deep shadow.

Fig. 8: Detail of the Great Wall at Deogarh, a small section of the sculptural remains (Photo courtesy Günter Heil).

The Department of Tourism has developed plans "to provide boating facilities in the Betwa River" and (as we also read in the Hindustan Times of 20-3-94) "to revive the traditional facade of the Jain temples through restoration work." Such statements are easily misunderstood. Deogarh has always been open to visitors, both Jainas and non-Jainas. Construction of roads and other measurements have changed the atmosphere of the locality to some extent, but not materially. Alterations in the archaeological substance will mainly be noticed by the specialists. Basically, Deogarh is still what it was, and those who see the place will be impressed by the splendour of its monuments and by the grandeur of primitive nature.

Impressions from Jain Temple site at Deogarh

Fig. 9: Courtyard of Temple No. 12 with reconstructed wall. The wall consists of numerous bas-reliefs (depicting Tirthankars and Jain deities) which were saved from the temple site.

Fig. 10: Reconstructed wall, made of bas-reliefs from the once ruined temple site.

Fig. 11: Bas-reliefs form the reconstructed wall beside Temple No. 12 (shikhara temple).

Fig. 12: Reconstructed wall, made of bas-reliefs from the once ruined temple site.

Fig. 13: Temple No. 12 with shikhara

Fig. 14: Tritirthika of a seated Tirthankara flanked by two standing Jinas.

Fig. 15: Pillar with figurative decoration.

Fig. 16: Sculpture of Suparshva with a five-headed serpent-hood flanked by two images of Parshva (seven-headed serpent-hood).

Fig. 17: Head of Suparshva (Detail of Fig. 16).

Fig. 18: Cāmara-bearer

Fig. 19: Female adorant, maybe a Yakshi, with a kalasha.

Prof. Dr. Klaus Bruhn

Prof. Dr. Klaus Bruhn