In the preceding discussion, the word "division" was used in the sense of a specific unit (value, class). It can, however, also be employed to designate the process of forming classes etc., and in this latter meaning (which is under consideration in the present section) we shall write the word invariably in capital letters. The term Division will cover at the same time the structure in its entirety which is graphically represented as a tree (tree graph, stemma).

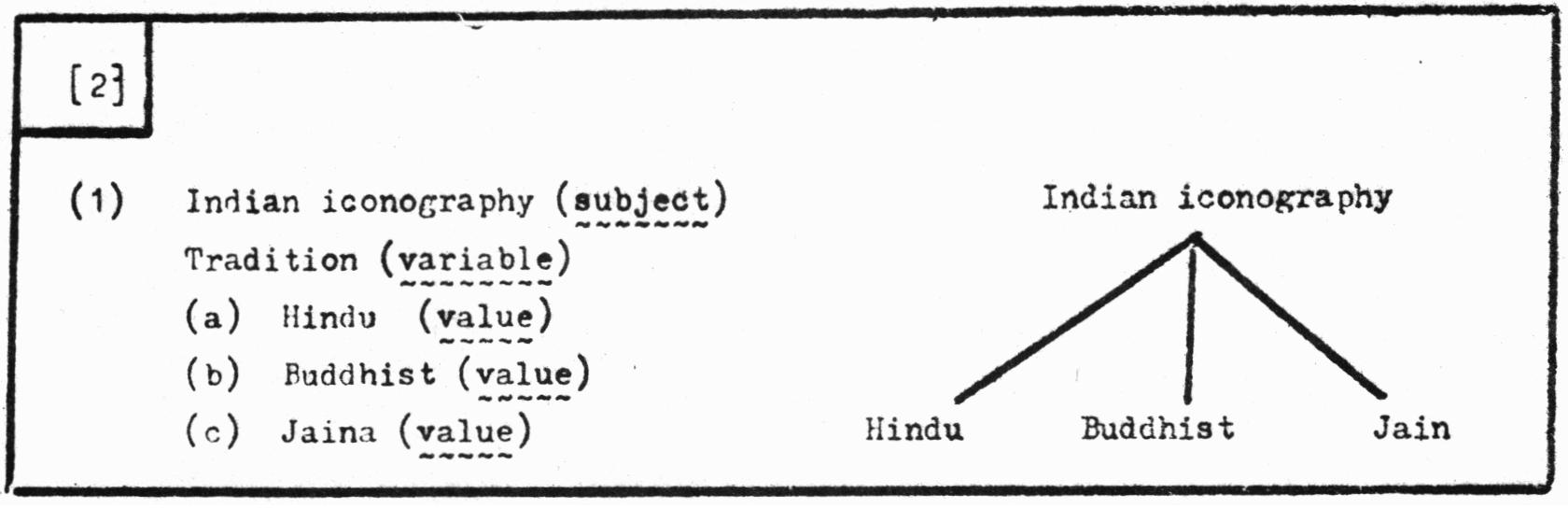

If the structure has only two planes, we prefer the presentation in lines to the tree formula: -

By contrast, the tree-formula is required whenever the structure has more than two planes (i.e. greater depth): -

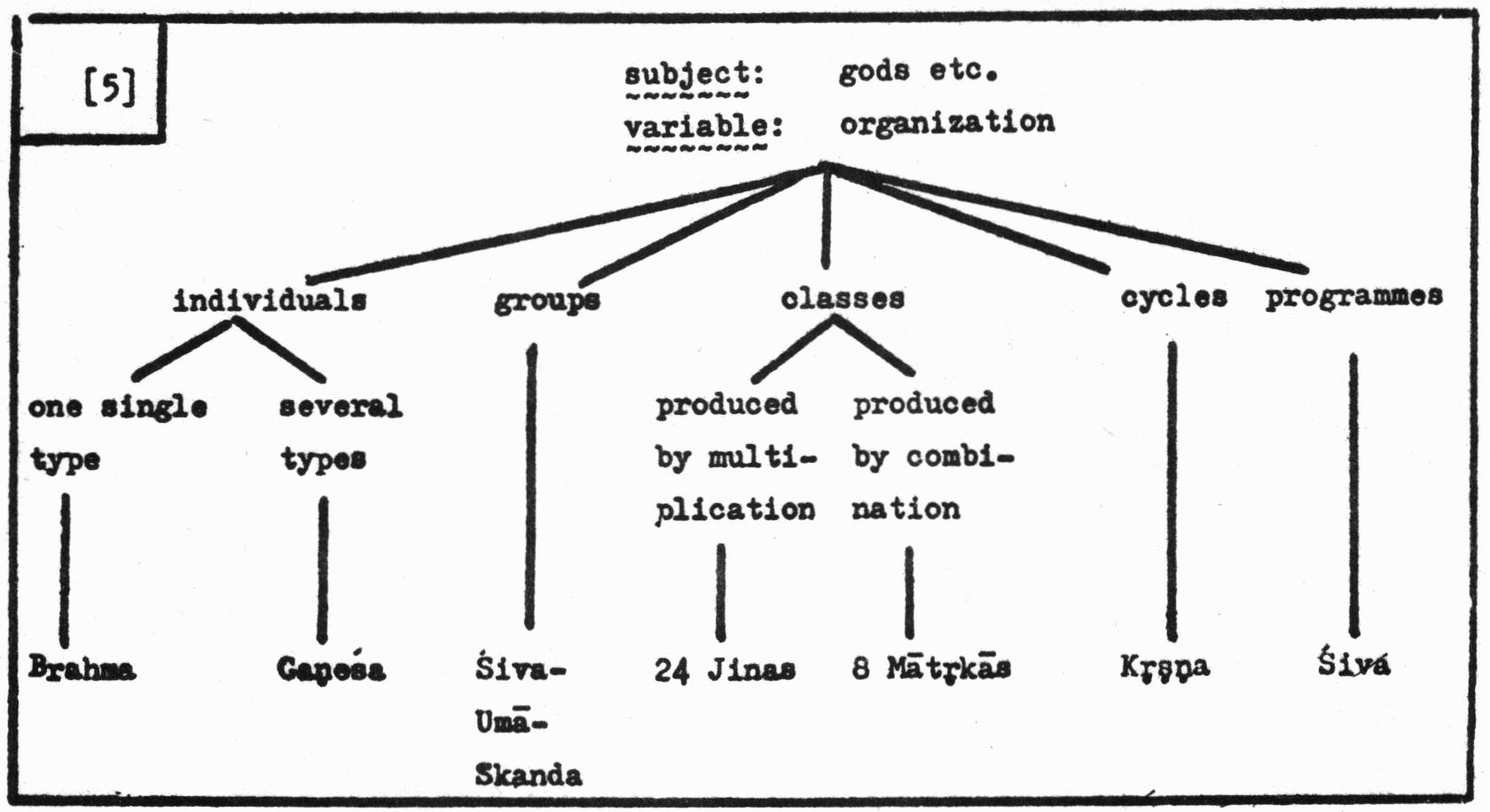

In the case of a structure with more than two planes the variable may change from plane to plane. In the above scheme, the variable is rather uniform, but there is a sudden change after the sixth plane. Character and value of structures showing great depth vary a good deal. In connection with [3] the objection may be raised that Kṛṣṇa iconography is different from "Viṣṇu" iconography and not just a subdivision of it (see § 3). Thus it might be better to exclude Kṛṣṇa iconography from Viṣṇu iconography and to consider only forms of Viṣṇu which are closer to the standard type (Varāha in his therio-anthropomorphic form, Trivikrama, and so on). In spite of such problems we supply two more examples for Divisions with more than two planes. The first example transgresses the boundaries of iconography: -

The second example is rather abstract and produces divisions which are for the most part not found in the literature on Indian iconography: -

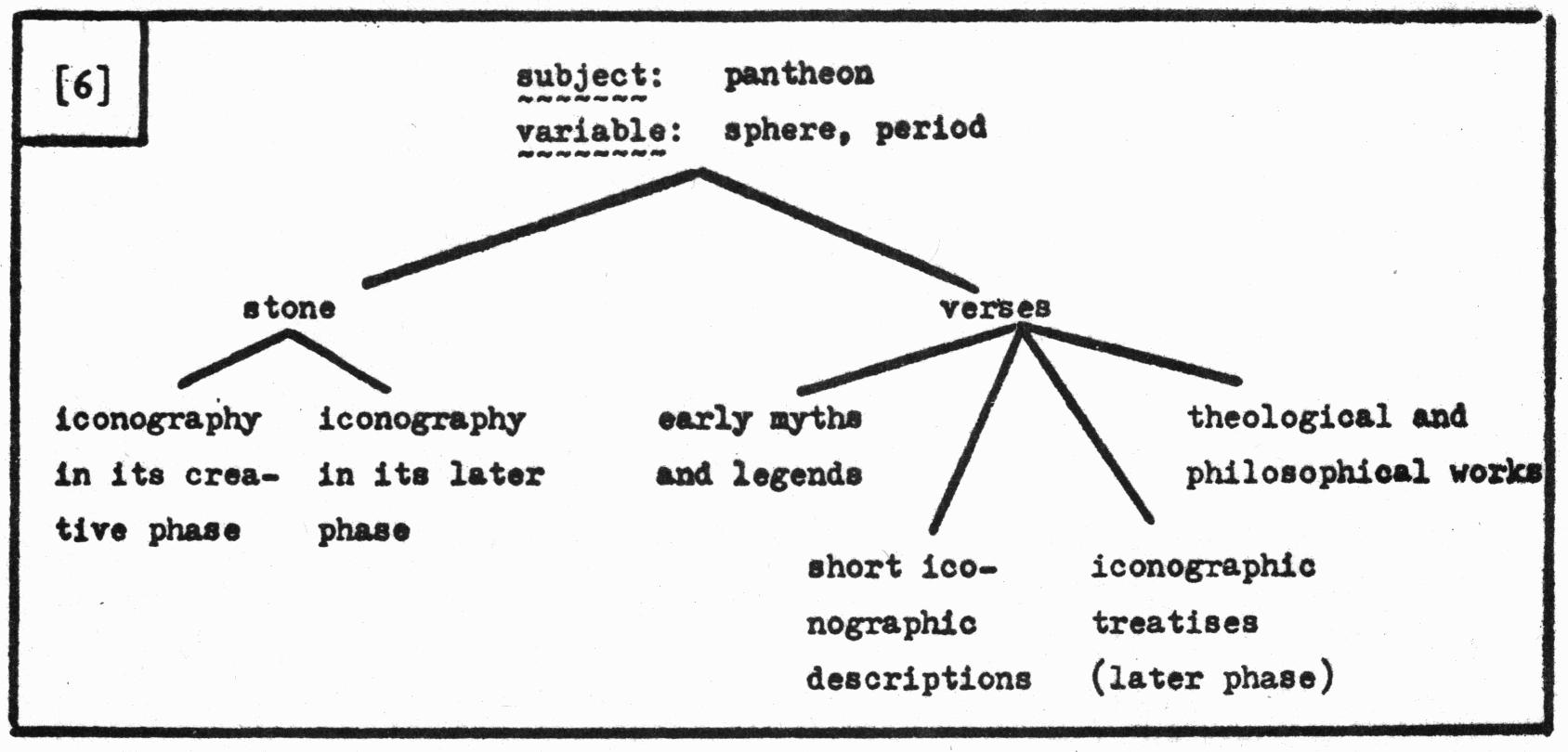

To the fore-going remarks we shall add an excursus touching upon a specialized problem. Identifications are expressed in sentences of the following type: This is the Jina Ṛṣabha, this image shows the Jaina goddess Apraticakrā. Such statements do not present any problems as long as the sculptor expressed in stone what the poet expressed in ślokas or verses. However, agreement of this uncomplicated type cannot always be taken for granted. Various spheres are involved which may but need not be in harmony: -

As a consequence, there may be disagreement of one type or the other. But even agreement may only reflect what can be described as "deceptive harmony". Thus the well-known motif showing Viṣṇu resting on the coils of the serpent Ananta is apparently "in complete agreement with the texts" (Mbh.3.203; 3.272). However, such an unqualified assertion would imply that the similarity with the earlier nāga motif (standing human figure with snake-coils behind it) is accidental. It would therefore be better to say that texts and sculptural representations converged at a point which was predetermined by an earlier motif.

We already indicated that Divisions are different in character. We may even say that they depend largely on the phantasy of an individual author as well as on the requirements of a specific case. Below we shall try to supply divisions (we may say: ad hoc divisions) for the classification of the 24 Jinas.

The dominant element in Jaina mythology and iconography are the 24 Jinas (mentioned already), which resemble one another, both in literature (24 biographies) and in art. They are represented in meditation, standing or seated (this posture is called in Prakrit kā'ussagga).

They never carry any objects in their hands. The differentiation between the 24members of the series is meagre and not very consistent (see p. 30 above), the result being some disproportion between the uncomplicated (but unfortunately irregular) procedure of the artists and the painstaking investigations which impose themselves on the modern scholar. Before we discuss the possible classifications of the 24 Jinas we shall try to describe the various patterns of differentiation which are in evidence. We could supply a tree graph for the subject of differentiation (and later on for the subject classification), but it seems that the lengthy discussion makes an additional graphical presentation superfluous.

Prof. Dr. Klaus Bruhn

Prof. Dr. Klaus Bruhn