Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

One of two schools which predominated pre-Mughal painting in northern India during medieval times, miniature painting of the 'Western Indian Style'flourished among Śvetāmbara communities in north-western India. In contrast to the Pāla-school of north-eastern India (Bihar and Bengal) where manuscript illustrations were drawn by Buddhist monks, the illustrated manuscripts of the Western Indian School were painted by craftspeople as commissions. Most of these works were Jaina religious manuscripts, a large number of which were copies of the Kalpasūtra.

The development of the Western Indian Style has remained largely unexplained. According to the Tibetan historian Tārānātha, who lived circa 1600, the Western Indian School was founded in the 7th century by Śṛṅgadhara from Marwar.[1] However, the earliest extant illustrations date from the 11th century. Although the Western Indian School of manuscript painting arose in Gujarat, this style was also prevalent in in Malwa (Madhya Pradesh) and the Jaunpur Sultanate, situated in north-eastern India. For this reason it is compelling to make a comparison of manuscripts that originated from these areas.

My PhD dissertation is based mainly on three illustrated Kalpasūtra manuscripts, two of which are preserved at the Berlin Museum of Asian Art (Inventory-nos. I 5040 and I 5042).[2] Both date from the 15th century and are typical examples of the Western Indian Style. Kalpasūtra Ms. I 5040 is completely preserved and was partially published by W. Hüttemann, while Kalpasūtra Ms. I 5042 is an unpublished fragment.[3] The third manuscript, and probably the most important of those which form part of my research, is the Kalpasūtra from Jaunpur (Yavanapura), dating from 1465 (V.S. 1522). In order to compare the stylistic characteristics of the manuscripts made in the homeland of the Western Indian Style with those from areas outside, such as the Jaunpur Sultanate or Malwa, I have also considered some single folios from other Kalpasūtra manuscripts, such as an example from Mandu (Maṇḍapadurga) dated 1439.

In addition to investigating stylistic development, the second focus of my dissertation is an analysis of the depicted scenes based on the canonical texts and related commentaries. Some of the miniatures depict scenes or include elements which are not contained in Kalpasūtra texts, e.g. the abhiṣeka ceremony (vide infra), hence the illustrations tell in part a version of the Jinacaritra extended to the text.

Regarding the style and ornamentation, the Jaunpur manuscript is of particular importance among the three mentioned Kalpasūtra manuscripts.[4] The Jaunpur manuscript contains 86 folios and was commissioned by Śrāvikā Harṣiṇī (harisinī-śrāvikayā), the daughter of the merchant Sahasarāja and the wife of Saṅghavī Kālidāsa of the Srīmālī caste. The name of the painter is also mentioned as Kāyastha Veṇīdāsa, son of Pandita Karmasiṃha Gauḍa.[5] The text is written in gold ink on a red background. The manuscript, with numerous illustrations and decorative borders, impresses with its beautiful ornamentation. The conservative style of the illustrations, however, forms a contrast to the variously shaped ornaments which show Timurid influence. In the second half of the 15th century, when the Jaunpur manuscript was produced, the tradition of the Western Indian School with its stylized and defined forms of expression had already been established in Gujarat and Rajasthan. At the same time the Jaunpur Sultanate, reigned by Husein Sharqi, was characterized by advances in the art of painting.[6] Therefore it is no wonder that new ornamental elements were added to the classical illustrations from which a characteristic Jaunpur School likely evolved. In addition to the aforementioned Jaunpur manuscript, there are fragments of not less than two more Kalpasūtra manuscripts preserved, which are of a similar style and are likely to have been executed in Jaunpur too.[7]

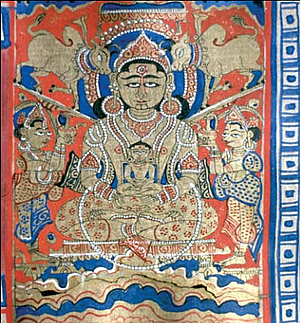

In addition to the stylistic aspects, for the purposes of understanding the depicted scenes an analysis based on the relevant textual sources is necessary. A case in point is the depiction of an abhiṣeka ceremony from the Kalpasūtra manuscript in the collection of the Berlin Museum of Asian Art. (Figure 1) The illustration depicts the god Śakra on a rock formation with Mahāvīra sitting on his lap. Śakra is flanked by standing male figures holding a pitcher and bulls standing on a platform above.

The occurrence of abhiṣeka (lustration, inauguration) is mentioned in the Kalpasūtra but not described in detail: 'After the Bhavanapati, Vyantara, Jyotishka and Vaimānika gods had celebrated the feast of the inauguration of the Tîrthakaras birthday...'[8] In the Ācārāṅgasūtra abhiṣeka is not mentioned. However, reference is made to a great lustre evoked by the descending and ascending of the gods and goddesses (Bhavanapatis, Vyantaras, Jyotishkas and Vimānavāsins).[9] Nevertheless, a depiction of the abhiṣeka ceremony is found in nearly every illustrated Kalpasūtra manuscript. Thus we may suppose that the abhiṣeka ceremony, which is primarily performed to consecrate a king,[10] evident by the form of the depicted pitchers,[11] became more important as a religious ritual in early medieval times.

Figure 1. Depiction of abhiṣeka ceremony (lustration of the Jina) Detail: Kalpasūtra manuscript folio Western India (Gujarat or Rajasthan) 15th Century © National Museums of Berlin, Prussian Cultural Foundation, Asian Art Museum, Art Collection South-, Southeast- and Central Asian Art (I 5040)

Abhiṣeka is described in Hemacandra's Triṣaṣtiśalākā puruṣacaritra:

The Indra of Aiśāna made himself five-fold [...] and took the Lord the Three Worlds on his lap. [...] Then the Indra of Saudharmakalpa created four bulls from crystal in the four directions from the Lord of the World. [...] The Blessed One, the first Tirthakṛt, was bathed by Śakra with the steams of water flowing from the horns resembling waterworks.[12]

These streams of water are depicted in the illustration. Hemacandra's description is very detailed, however the Triṣaṣtiśalākāpuruṣacaritra is not the literary source. In fact this is found in the 6th Upāṅga of the Jaina canon, titled Jambūdvīpaprajñapti, where in the 5th chapter a detailed description of the abhiṣeka ceremony is given.[13] The consecration occurs at the Paṇḍaga grove, situated on the summit of Mount Meru. Śakra is sitting on the abhiseya-sīhāsaṇa, which is placed on abhiseya-silā. According to the Jambūdvīpaprajñapti the abhiṣeka is performed by Accuya, who needs a large number of objects for the ritual. Numerous gods, first and foremost the 63 Indras, attend the ceremony and are involved in the performance of abhiṣeka. One of the two gods depicted in the illustrations is probably Accuya, while the other is representing the numerous gods.

In conclusion, it is evident that the miniatures are not comprehensible solely on the basis of reading the text. In fact an investigation which includes all relevant textual sources is indicated in order to understand the elements depicted in the scenes, especially those which are not mentioned in the Kalpasūtra.

Patrick F. Krüger is visiting lecturer on History of South Asian Art and Jaina Studies at Freie Universität Berlin.

The working title of my PhD dissertation is 'Aspects of Kalpasūtra Paintings'. Since previous research on the topic by Nawab, Brown etc. discounted several aspects it seems reasonable to discuss the subject again and, additionally, to publish the complete illustrations of the Jaunpur Kalpasūtra and the manuscripts from the Berlin Museum of Asian Art.

Wilhelm Hüttemann, Miniaturen zum Jinacaritra, Bässler Archiv, Vol. 4, Leipzig/Berlin 1913. Hüttemann's essay, one the first publications on Jaina miniature painting in Germany, is a pioneering study of Jaina art but contains some misinterpretations. Thus, a new investigation of this manuscript is needed.

The manuscript was formerly part of a collection of other Kalpasūtras of the late Hamsavijayajī. Later, it was preserved in the Narasimhaji ni polnā Jñāna Bhaṇḍāra, Vadodara. The current disposition is unknown.

Karl Khandalavala/Moti Chandra, 'An Illustrated Kalpasūtra Painted at Jaunpur'. In: Lalit Kalā, No. 12 (1962), p. 12.

Mian Muhammad Saeed, The Sharqi Sultanate of Jaunpur. A Political and Cultural History. Karachi 1972, p. 208f.

Phyllis Granoff (Ed.), Victorious Ones. Jain Images of Perfection, New York 2009, p. 224 and Catalogue entries P 08, P 09 and P 10.

Ācārāṅgasūtra II, 15 ('Bhāvanāḥ') contains a biography of Mahāvīra which is certainly older than the Kalpasūtra. Bhāvanāḥ is not referring to abhiṣeka, but the gods and goddesses (Bhavanapatis, Vyantaras, Jyotishkas and Vimānavāsins) are mentioned instead on the occurrence of a great lustre, evoked by their descending and ascending.

Since early times, pouring water from this type of vessel (Skr. bhṛṅgara) was used to seal a deal or an act in the law. There is a depiction of a bhṛṅgara on a bas-relief at Badami which shows a horse sacrifice (aśvamedha).

Hemacandra, Triṣaṣtiśalākāpuruṣacaritra, Vol. I Ādīśvaracaritra, Translated into English by Helen M. Johnson, Baroda 1931: p. 125.