Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

There are thousands of medieval copper-alloy icons in temples in western India today, and dozens in museum collections. Often overlooked, some of these icons offer an insight into medieval ritual culture and are well worth investigation. One such example is a medieval Digambar Jain copper-alloy icon that was recently donated to the Ackland Art Museum at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The sixteenth-century icon, from Gujarat, depicts the twenty-four Jinas, with the central seated figure being the sixteenth Jina Śāntinātha. It has a detailed inscription, which tells us that the icon was consecrated in 1511, and gives us valuable information about both the lay patron and the consecrating monk.

Śāntinātha, to whom the icon is dedicated, and whose presence is consecrated into it, sits in the center on a cushioned throne that is supported by two lions, and hence known as a 'lion-throne' (siṃhāsana). Immediately below the cushion is a lightly etched deer, the symbol (lāñchana) of Śāntinātha. Below the throne are two deer flanking a dharmacakra ('wheel of the law'), a symbol found on most Jina icons over the past millennium. Behind Śāntinātha is a halo (bhāmaṇḍala), a sign of his divinity.

At the base of the icon is a much abraded two-armed goddess. In Śvetāmbar ritual culture, this goddess is known as Śāntidevī, and her worship arose in the tentheleventh centuries. She is understood to bring peace to the ritual setting, and thereby protect it. As a result, her icon is often found at the base of copper-alloy icons, and in the base of stone altars in temples. Scholars have identified her as a distinctly Śvetāmbar goddess, and so at first sight her presence on a Digambar icon might be surprising.However, a perusal of published medieval Digambar copper-alloy icons from western India shows that others also include Śāntidevī, so we see here one among many ways that the ritual cultures of the two traditions have interacted.[1]

The bottommost register of the icon includes small figures of the nine planetary deities (nava-graha). These serve to protect the icon and its worshipers from possible inauspicious affects from the planetary cycles. At the outmost edges of this register, on the bottom corners, are found the patrons of the icon, the husband on the right and the wife on the left. They are seated with their hands folded in front of them in homage to the Jina. (The inscription indicates that the male patron, Jayatā, was joined in commissioning this icon by two wives, Rahī and Nāthī. Only one of them, however, is represented on the icon.)

On the second register from the bottom, flanking the two lions of the lion-throne, are two-armed figures of Garuḍa Yakṣa (r) and Mahāmānasī Yakṣī (l), the guardian deities associated with Śāntinātha. While larger icons of these deities have distinct iconographies, in the case of these small figures there is nothing to identify them except their association with Śāntinātha. Outside of them at each end of the register are divine figures bringing garlands of flowers to worship the Jina.

Twenty-four Jina icon of Śāntinātha Gujarat, dated VS 1567 = 1511 CE. Copper alloy, 27.3 x 9 x 18.5 cm Ackland Art Museum, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gift of the Rubin-Ladd Foundation. 2011.34.1

In the central panel of the icon, surrounding the main icon of Śāntinātha, are four other Jinas, making the central panel into a pañca-tīrthī, or 'five icon' set. The concept of worshiping five Jinas together is an ancient one in Jainism. The five can symbolize the five parameṣṭhins or five supreme lords of Jainism (Arihanta or Jina, Siddha, Ācārya, Upādhyāya, and Sādhu), as well as the five most popular Jinas from early in the tradition (Ādinātha, Śāntinātha, Neminātha, Pārśvanātha and Mahāvīra). On both sides of Śāntinātha are two Jinas, the lower one standing and the upper one seated. Above the two sitting Jinas are elephants with their trunks upraised, in the gesture of auspiciously lustrating the Jina. Directly above Śāntinātha is a parasol, atop which is a small figure of a crouching deity with hands folded in homage. This deity who is worshiping Śāntinātha is one of the Indras, who are the paradigmatic worshipers in Jainism.

Outside the central panel, are vertical rows of four seated Jinas, one row on each side. Outside them, at the edges of the icon, on both sides is a standing figure holding a small fly-whisk on the bottom, and an elaborate antelope-shaped griffin.

In the register immediately above Śāntinātha are seven seated Jinas, with an auspicious makara at either edge of the register. The topmost semicircular compartment contains the remaining four seated Jinas, in one row of three (with the outermost two underneath small parasols) and a solitary Jina at the top of the compartment. To either side of this semicircle is a finial shaped like an auspicious full-pot, and a third such finial caps the entire icon. The total number of Jinas in the icon is therefore twenty-four, and so the icon is known in Sanskrit as a caturviṃśikā and in the vernacular as a covīsī. These are the twenty-four Jinas of this cycle of time. Even though larger icons of Pārśvanātha and Supārśvanātha are identifiable by the serpent-hoods above their heads, and older icons of Ādinātha are identifiable by the locks of hair hanging down on his shoulders, in a set of twenty-four Jinas these identifying features are usually missing, as they are here. Except for the central figure of Śāntinātha, whom we can identify both by the deer lāñcana and the text of the image's inscription, none of the Jinas is identifiable. This underscores the Jain understanding of liberated souls as being identical.

While we know from the inscription on the back of the icon that the consecrating monk was Digambar, and therefore the icon itself was Digambar, the only way the sectarian identity of the icon is immediately obvious is from the nudity of the two standing Jinas. In the case of this icon, however, these two figures possibly reveal an interesting history to it. In both cases the male genitalia have been smoothed off. This is especially noticeable on the right figure. While this could simply be the result of the centuries of lustration and other ritual acts, this is an unlikely explanation for such a complete effacement of the genitalia.[2] It is more likely that this Digambar icon at some point in the past came into the possession of a Śvetāmbar devotee or temple, and the icon was visually 'converted' to mark its new sectarian status. There are many such icons in Śvetāmbar temples in western India.

Copper-alloy Jain icons from western India usually have inscriptions on their backs that provide us with information concerning the date of consecration, the lay patrons, the consecrating monks, and sometimes the residence of the patrons. This icon is no exception. The inscription, which is in indifferent inscriptional Sanskrit, reads as follows.

Twenty-four Jina icon of Śāntinātha (back with inscription) Gujarat, dated VS 1567 = 1511 CE. Copper alloy, 27.3 x 9 x 18.5 cm Ackland Art Museum, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gift of the Rubin-Ladd Foundation. 2011.34.1

saṃ° 1567 varṣe vaiśākha sudi 15 some śrī mūla saṅghe sarasvatī gacche balātkāra gaṇe śrī kuṅdakuṅdācāryānvaye bha° śrī sakalakīrtti sta° bha° śrī bhuvanakīrtti sta° bh° śrī jñānabhūṣaṇa sta° bha° śrī vijayakīrtti gurūpadeśāt hu° śre° jayatā bhā° rahī bhā° nāthī bhrā° vasu śre° bhojā śre° bhojā su° veṇā // nā bhā° jāsī su° rāṇā bhā° māṇikī bhrā° mākā kīkā śrī śāṅtijinaṃ nitya praṇamaṅti.

In translation, it reads:

In the year VS 1567 [= 1511 CE], on the 15th of the bright half of [the month of] Vaiśākha [AprilMay], a Monday. In the blessed Mūla Saṅgha, in the Sarasvatī Gaccha, in the Balātkāra Gaṇa, in the Anvaya of blessed Kundakunda, at the instruction of the guru bhaṭṭāraka blessed Vijayakīrtti, disciple of bhaṭṭāraka blessed Jñānabhūṣaṇa, disciple of bhaṭṭāraka blessed Bhūvanakīrtti, disciple of bhaṭṭāraka blessed Sakalakīrtti By the merchant Jayatā, of the Humbaḍa caste, with his wife Rahī and wife Nāthī; his [Jayatā's] brother Vasu; his [Jayatā's] son [by Nāthī] Bhojā; Bhojā's son Veṇā; his [Veṇā's] wife Jāsī and son Rāṇā; his [Rāṇā's] wife Māṇikā; and her [Māṇikā's] brothers Mākā [and] Kīkā: they bow forever to the blessed Jina Śānti.

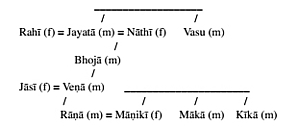

The date of the inscription probably corresponds to Monday, May 12, 1511 CE. From this inscription we learn that this icon was commissioned by an extended merchant family, covering four generations, of the Humbaḍa caste. The family relationships can be seen more clearly in the following chart:

The Humbaḍa is a Vāṇiyā (mercantile) caste, in earlier centuries found largely in the area of northeastern Gujarat and southeastern Rajasthan. While this is a border area between the Gujarati and Rajasthani cultural regions, the Vāṇiyās of the area have been largely Gujarati speakers. According to R. E. Enthoven, writing in 1922 (and depending on information from the earlier, 1901 Bombay Gazetteer), the Humbaḍa were centered around Sagwara, in the southeastern part of what is today Dungarpur District in Rajasthan.[3] Many inscriptions on Digambar icons from medieval western India do not include information concerning where the donor resided, and this icon is no exception. According to Buddhisāgarsūri,[4] Humbaḍa Vāṇiyās are both Digambar and Śvetāmbar, and there is extensive religious interaction among them, so this icon may have been 'converted' from Digambar to Śvetāmbar when the family to which it belonged shifted allegiance from a Digambar monastic lineage to a Śvetāmbar one.

The icon also gives us information concerning Vijayakīrtti, the bhaṭṭāraka who consecrated the icon. The inscription gives his lineage: Sakalakīrtti > Bhūvanakīrtti > Jñānabhūṣaṇa > Vijayakīrtti. The inscription further gives information concerning the lineage of this seat of pontiffs. Three of the names of the lineage of these pontiffs are largely synonymous. The lineage is declared to be the 'Root Congregation' (Mūla Saṅgha), the 'Lineage dependent on Sarasvatī' (Sarasvatī Gaccha), and the 'Spiritual Descendants of Kundakunda' (Kundakunda Anvaya). The more specific identification is that these monks were in the Balātkāra Gaṇa. This was one of the more important medieval lineages of bhaṭṭārakas, with many localized seats. The earliest references to this lineage come from Karnataka in the eleventh century, but references from soon thereafter are found from many north Indian locales. Johrāpurkar gives inscriptional evidence from ten branches.[5] One of these had its seat in Idar, in northeastern Gujarat in contemporary Sabarkantha Districtin other words, precisely the area where Jayatā and his extended family lived.

According to the evidence gathered by Johrāpurkar, the Idar seat began with Sakalakīrtti. The bhaṭṭārakas of this seat served as caste gurus for the Humbaḍa Vāṇiyās. Inscriptions and text colophons indicate that Sakalakīrtti was active between VS 1450 and 1510 (1394-1454 CE). In addition to consecrating icons, he was author of a number of Sanskrit texts. He was succeeded on the seat by Bhuvanakīrtti, who was active VS 1508-1527 (14521471 CE). Several of his mendicant disciples were active in the composition of vernacular texts. The third monk on the seat was Jñānabhūṣaṇa. He was active VS 1534-1560 (1478-1506 CE), and was honored by several small-scale rulers from Karnataka. He also was an author in Sanskrit, and oversaw other monks who were active litterateurs. Jñānabhūṣaṇa's successor was Vijayakīrtti. Inscriptions indicate he was active VS 1557-1568 (1501-1512 CE). He was also honored by three small-scale rulers from Karnataka.

In VS 1557 (1501 CE), Vijayakīrtti consecrated a twenty-four Jina icon of Śāntinātha for a family of Humbaḍas who lived in Kheralu, a town about twenty miles west of Idar in contemporary Mehsana District. As of 1917, this icon was located in the Śvetāmbar Śāntinātha temple in Visnagar, about fifteen miles southwest of Kheralu.[6] While the condition of this icon is not described, its current location in a Śvetāmbar temple is perhaps illustrative of the history of the icon now in the collection of the Ackland Art Museum.

According to Johrāpurkar, three years later, in VS 1560 (1504 CE), Vijayakīrtti consecrated another icon of Śāntinātha for a Humbaḍa family. That both the 1501 and 1504 icons, in addition to the Ackland Art Museum' s icon of 1511, are of Śāntinātha, might indicate that Vijayakīrtti had a devotional preference for this Jina. However, two other icons that we know Vijayakīrtti consecrated are not of Śāntinātha, so we can say nothing definitively about any particular devotional orientation. In VS 1561 (1505 CE), Vijayakīrtti consecrated an icon of Nemīnātha for a Humbaḍa family. This icon is also now in a Śvetāmbar temple, in Pethapur, just to the north of Gandhinagar. In VS 1561 (1505 CE), he consecrated a ratna-traya ('Three Jewels') icon.[7] This is an icon with three standing Jina figures as the central deities. It is now in the Senagaṇa Digambar temple in Nagpur, Maharashtra.

We know of one other icon that Vijayakīrtti consecrated. In VS 1567 (1511 CE; the printed text has VS 1667, which must be a mistaken reading or else a typo) he consecrated a Jina icon now in the Śvetāmbar temple in the Dhandhal section of Salvi Vado in Patan.[8] The printed text provides neither the caste of the lay patron, nor the Jina of the icon.

Johrāpurkar lists fourteen bhaṭṭārakas, culminating in Yaśaḥkīrtti, on the Idar seat. In VS 1863 (1807 CE), he arranged for the construction of a wall at the famous pilgrimage shrine of Keśariyājī in southern Rajasthan. Johrāpurkar adds that according to Brahmacārī Śītalprasād, there were four further bhaṭṭārakas, ending with another Vijayakīrtti.[9] The lineage was allowed to lapse by the Digambar laity who would have had to financially support it. This was part of a broader process in the late-nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries, by which all bhaṭṭāraka seats in North India were allowed to lapse. The reference to Keśariyājī may indicate that the last few bhaṭṭārakas of the Idar seat of the Balātkāra Gaṇa, like many of the bhaṭṭārakas of other north Indian seats that faced a decline in lay support, shifted their attention and perhaps even residence to this pilgrimage center. This short essay indicates some of what can be learned from the close inspection of just a single icon. The inscription certainly aids in our understanding of it, but even without an inscription this icon is a rich source of information about the ritual culture of medieval Digambar Jainism.

The author thanks Surendra Bothara, Peter Nisbet, Gary Tubb and Mahopadhyaya Vinayasagar for their help in preparing this notice.

Inscribed bolder at Candragiri, Śravaṇabeḷagoḷa

John E. Cort is Professor of Asian and Comparative Religions at Denison University in Granville, Ohio, USA.

For example, a Digambar icon dated 1447 is published in Van Alphen, Jan (ed.). Steps to Liberation: 2,500 Years of Jain Art and Religion, Antwerp: Etnografisch Museum Antwerpen, India Study Centre Universiteit Antwerpen, and Antwerp Indian Association, 2000, 159.

In India, the material of an icon such as this one is called pañcadhātu, or "five metals." These are usually gold, silver, copper, tin and zinc, although in some formulations lead is one of the five. The first two tend to be found in minute quantities, in amounts donated by the patron of the icon. The main metal is copper. The copper alloy needs to be soft enough to be worked to form the finely-wrought final product. Being composed of a soft copper alloy results in the icons becoming very worn through the act of worship. Daily lustration (abhiṣeka) is performed to a consecrated Jina icon, followed by drying with a cloth to ensure that no water remains on it, as the water might become the site of the birth and death of micro-organisms. Further acts of worship include dabbing a fragrant paste of sandalwood (and perhaps saffron and camphor). All of this wears away the surface details, and after centuries of worship many Jain icons are in a condition similar to this one.

Enthoven, R. E. The Tribes and Castes of Bombay, Vol. 3. Reprint Delhi: Cosmo Publications, 1922/ 1975, p. 438.

Buddhisāgarsūri, Ācārya. Jain Dhātupratimā Lekh-saṅgrah, Vol.1. Bombay: Śrī Adhyātma Jñān Prasārak Maṇḍaḷ, 1918, pp.16-18.

Johrāpurkar, Vidyādhar. Bhaṭṭārak Sampradāy. Sholapur: Jain Saṃskṛti Saṃrakṣak Saṅgh, 1958. Johrāpurkar tends to correct the Sanskrit of the names of the bhaṭṭārakas of this lineage, and so spell their names with kīrti. I prefer to honor the localized spelling of the inscription of the Ackland Art Museum (and other) icons, and so spell their names with kīrtti.

See: Van Alphen, op. cit., p. 159 for an example of a ratna-traya icon, consecrated in VS 1504 (1448 CE), also from Gujarat. The author of the catalogue entry for this icon, Lalit Kumar, wrote that these icons are relatively rare. Another such icon, from VS 1549 (1492 or 1493 CE), also from western India, is in the collection of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco (Robert J. Del Bontà, "Jaina Sculpture at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco." Jaina Studies: Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies 5, 2010, 42-3). The San Francisco icon was consecrated by Jinacandra, who occupied the seat of the Delhi-Jaipur branch of the Balātkāra Gaṇa from VS 1507 until 1571 (1450-1514 CE) (Johrāpurkar 1958:108-10).

Lakṣmaṇbhāī Hī. Bhojak. Pāṭaṇ Jain Dhātu Pratimā Lekh Saṅgrah. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass; and Delhi: Bhogilal Laherchand Institute of Indology, 2002, p. 183.

Prof. Dr. John Cort

Prof. Dr. John Cort