Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

When illustrating the lives of the Jinas, it is typical to use examples from the Śvetāmbara Kalpasūtra, and many paintings from manuscripts of it have been published over the years. One might get the impression that this text is the only one to recount the lives of the Jinas, but there are actually many such texts in a variety of languages that tell the stories of these tales in much greater detail. The Digambara Jainas also wrote versions of the lives of the Jinas and illustrated manuscripts survive, but in far fewer numbers.

Paintings from these manuscripts sometimes differ significantly from Śvetāmbara accounts. A famous early manuscript, and an important document of early painting from northern India, is an illustrated Ādipurāna by Puspadanta produced at Palam (the location of Delhi's airport) in 1541 CE.[1] Digambara authors wrote many Ādipurānas, versions of the life of the first Jina, Rsabha. These include stories of his family, principally his son Bharata, but also of Bharata's younger brother Bāhubali. There are also numerous other stories about the later Ji- nas told in separate texts; the overall title for a work combining the entire series is Mahāpurāna.

It must be recalled that Rsabha's life is included in the Śvetāmbara Kalpasūtra, but in that work Mahāvīra's life is told first and gets the most attention (Del Bonta 2007). In most of Illustrated Kalpasūtras have very few illustrations depict Rsabha's life story, except in profusely illustrated ones. This might be because the Kalpasūtra is actually a rather short work.

The various Ādipurānas and Mahāpurānas are much longer and contain elaborate narratives. The Śvetāmbara also wrote longer accounts of the lives of the sixty-four auspicious persons corresponding to the Digambara Mahāpurāna, but I have not seen any illustrated examples from those works. The most accessible Śvetāmbara account, to be mentioned below, is the twelfth century Trisastiśalākāpurusacaritra by Hemacandra (1931).

Rather than revisit the Digambara Palam manuscript with its lively, but rough style, I will now turn to some later paintings produced for the Digambara Jainas in Rajasthan and the northern Deccan, and entertain some comparisons with important Digambara paintings at Śravanabelgola in Karnātaka and Tiruparuttikunram in Tamilnādu.

Two north Indian series of paintings stand out. One is a long cloth painting or pata (Doshi 1978). Produced around 1700, it illustrates the pancakalyānaka (the five auspicious key events in the lives of all of the Jinas) of the first Jina, Rsabha. The other is a series of paintings on the same subject, recently re-dated to around 1680 at Amber, the ancient capital of Jaipur State. Its compositions appear to be closely related to the cloth painting, which was produced around twenty years later. Initially, the Jaina nature of the paintings was missed, but in 1995 it was identified as relating to a Digambara version of Rsabha's life (Pal 1995, no. 107a).[2]

The painting from the series illustrated in The Peaceful Liberators (Pal 1995, no. 107a) concerns the episode after the birth of Rsabha when the baby was taken to be lustrated by Indra. Another folio from the series, in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (M.74.102.4), suggests a scene from before the lustration when Indra and Indrānī came to fetch the child. The inscriptions on these paintings clearly refer to the god as Indra, rather than the Śakra of the Śvetāmbara tradition. Even without the inscriptions it is clearly a Digambara work. In that tradition, at the birth of a Jina, Indra arrives on his elephant to take the infant for lustration. Figure 1, from the pata, depicts Indra on his elephant during the festivities for the infant Rsabha. Digambara versions of the lustration of infant Ji- nas often describe the elephant, which is absent from the Śvetāmbara Hemachandra account (1931: 105ff.).

An elephant is depicted in all of the birth stories of the major series of Digambara illustrations that I have seen:

(Figure 2)

The Birth Ceremonies of Nemi

Sangīta Mandapa, Vardhamāna temple, Tiruparuttikunram, circa 18th century. Mural.

Photo: Del Bonta

(Figure 1) Indra on Airāvata Pancakalyānaka pata Aurangabad circa 1700

Ink, opaque watercolour, and gold on cloth Photo: Courtesy of Saryu Doshi

(Figure 3) Janmābhiseka of Rsabha, Pancakalyānaka pata, Auranga- bad, circa 1700. Ink, opaque watercolour, and gold on cloth. Photo: Courtesy of Saryu Doshi

the pata, the Amber set, the story of the life of Pārśva from the Jaina Matha at Śravanabelgola and a number of instances in the painted series at Tiruparuttikunram, sometimes referred to as Jina-Kāncī in Tamilnadu, as seen here at the birth of Nemi. (Figure 2) Often, as in Figure 1, the depiction of the elephant is extremely elaborate and follows Digambara descriptions with multiple trunks and tusks and even with ponds sprouting lotuses which support dancing figures. An elephant representing the birth festivities of Pārśva is similarly handled with multiple tusks at Śravanabelgola in the murals at the Jain Matha, but lacks the ponds and dancing figures. The scene is also depicted in the Palam manuscript as illustrated by Doshi (1985: 95).

In both the Digambara and Śvetāmbara traditions there is a multiplication of Indras/Śakras, who can be considered as either a number of gods who rule particular regions, or various versions of the same figure. But Indra's elephant is not mentioned at the birth of Rsabha in the Hemacandra text (1931: 110 ff.): there Śakra arrives in an elaborate vimāna or aerial car. Hemacandara (1931: 188 ff.) does describe this magical elephant at Rsabha's samavasarana, or teaching after his enlightenment. Elephants do appear in Kalpasūtra illustrations, but they appear for different episodes and usually as vehicles for people and not gods (Brown: 1934: figs. 65, 68, 122-23, and 127). I have seen only one example of Indra riding an elephant for the birth ceremony. Elsewhere I have argued that the illustrator was influenced by a Digambara tradition (Del Bonta 2004: 215-16).

Although the title pancakalyānaka refers to the five crucial events in the lives of all of the Jinas, both the pata and the Amber set include many scenes from the life of Rsabha which are particular to his story. There are also added events in recounting the Jinas' lives in the Śvetāmbara Kalpasūtra such as Nemi's renunciation after his hearing the cries of the animals to be slaughtered for his wedding, and the peculiar events surrounding Pārśva's life and its association with snakes. As pointed out in Brown (1934) many of these specific events are implied in the text itself and reflect knowledge of the longer Śvetāmbara versions of these stories. While the Kalpasūtra tells the life of Mahāvīra at the greatest length, in Digambara literature the life of Rsabha appears to be primary, since he was the first tirthankara. In addition to accounts in literature, vast mural schemes at some of the important centres, indicate that a number of the other Jinas had extensive stories told about them as well. At Śravanabelgola in the paintings at the Jain Matha, a great deal of space is taken up with the stories of the various incarnations of Pārśva (Doshi 1981: 108-39), while at Tiruparuttikunram extensive stories are told of three: Rsabha, Mahāvīra and Nemi (Ramacandran 2002). Among the Nemi sections important Jaina versions of Krsna's life are depicted as well, since he was part of Nemi's family.

Linked with the depictions of the elephant taking the infant for his janmābhiseka, the birth-lustration, is the manner of the lustration itself. The child is lustrated at birth on Mount Meru in both traditions. But the lustration of the baby Jina is illustrated differently in Śvetāmbara and Digambara paintings. The usual Kalpasūtra version of the lustration merely has the baby Jina seated in the lap of Śakra and the figure is lustrated with water flowing from the horns of bulls (Hemacandra 1931: 125 and Del Bonta 2007: 30).

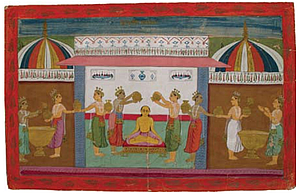

The Digambara version is seen in the lustration of the infant Rsabha on Mount Meru from the pata. (Figure 3) This way of depicting the mountain as a stepped pyramid is another feature common in Digambara illustrations. It suggests the height of Mount Meru and gives places for the multiple Indras to stand while passing the pots up to the top. Figure 4 illustrates a similar scene taking place on a stepped pyramid-like mountain from the Jaina Matha at Śravanabelgola. This time the ritual is for the infant Pārśva. Another painting, now in the Berkeley Art Museum, from a Nemipurāna from Rajasthan of ca. 1625-75 shows a similar scene for the Jina Nemi. (Figure 5) Here he is seated in the crescent shaped siddhaśilā, which is reminiscent of the apex of the world space (loka-ākāśa). This could suggest a lustration after Nemi's moksa, but the size of the infant lets us know that this is at his birth. In any case, the lustration of the bodiless Jina after moksa would be inappropriate. The eight auspicious symbols are seen to the side of the lustration scene and musicians and dancers celebrate the event as the water from the ritual cascades in a zigzag pattern from the mountain peak. These paintings and the following example illustrate constant motifs found in Digambara imagery that spreads both over a large area and time.

This pouring of fluids over the Jina's head is a frequent ritual in Digambara iconography. It is also seen in Figure 2 from Tiruparuttikunram. One can just make out the pots around the figure of the baby Nemi in the pavilion to the right. The scene reads from right to left. Four Indras perform the janmābhiseka ceremonytwo lift pots to each side of the child and two more are to the sides of the pavilion. Gold pot-like elements also adorn the roof of the pavilion. To the left the baby is taken back to the city atop the elephant and put on the throne; the figures to his sides in the throne scene at the left hold cauris, yak-tail fly-whisks. The lustration with pots appears to be a consistent ritual in Digambara illustrations.[3]

Right after the birth of Rsabha, Hemacandra (1935: 118 ff.) describes the use of pots for the janmābhiseka, but all the Kalpāsutra examples that I have seen illustrate the later scene when Śakra takes the baby in his lap. The illustrations often show figures on either side holding spouted jars rather than the cauris described in text (Hemacandra 1935: 125 and Del Bonta 2007: 30, fig. 4).

(Figure 4) Janmabhiseka of Parśva, From the Jaina Matha, Karnātaka, Śravanabelgola, Circa 1825-50. Mural. Photo Del Bonta

(Figure 5) Janmābhiseka of Nemi, Folio 45 (recto) from a Nemipurāna loose-leaf manuscript. Rajasthan, Marwar, probably Jodhpur, circa 1625-75. Ink, opaque watercolour, and gold on paper. (Berkeley Art Museum 1998.42.104.2) Courtesy of the Berkeley Art Museum, Photo: Del Bonta

This Digambara manner of lustration is used in other places in the narrative. One folio from the Amber series is that of Rsabha lustrated as the first king. (Figure 6) This is an event peculiar to his life story and is also seen in the pata. In both instances multiple crowned Indras pour the fluid from pots over the head of Rsabha. Curiously, for the lustration as king, rājyābhiseka, Hemacan- dra (1935: 148 ff.) states that this is not to be done: " 'It is not proper to throw it on the Lord's head since he is adorned with divine ornaments and clothes.' They threw the water at his feet." For those used to Śvetāmbara imagery, this scene may suggest a lustration of the Jina after his enlightenment, but one must remember that this is a Digambara image, and the fact that the figure of Rsabha is clothed in both illustrations and crowned in the pata rules out that interpretation. The scene from the Palam manuscript has men in turbans approaching with pots to lustrate the crowned Rsabha on a throne (Khandalavala 1969: 72). I have found only one published illustration of the rājyābhiseka ceremony from a Kalpasūtra manuscript (Brown 1934: fig. 121) where Śakra merely applies the tilak to the forehead of Rsabha.

It is clear that head anointing is very important in Digambara ritual, notably in the ritual for Bāhubali at Śravanabelgola. While at Tiruparuttikunram the scene of Rsabha's coronation is worn away, other installations of kings are depicted, as in the coronations of Nami and Vinami, where the figure of Dharanendra merely applies the tilak to their foreheads (Ramachandram 2002: pl. XV). What appears evident is that this lustration with pots by the Indras is exclusive to Jina figures, whether at their births or other important moments in their lives. It appears inappropriate for other figures. John E. Cort (2001) has discussed differences in Digambara contemporary ritual practices in Jaipur and Karnātaka, where he demonstrates that abhiseka is now most common in the southern areas.

Too few paintings from Digambara series are documented to enable a complete picture of the consistencies and inconsistencies in the visual depictions of the stories from the lives of the Jinasbut it is clear from the few comparisons entertained here that there are clear patterns found throughout India in both northern and southern painted series. In turn, the un-illustrated narrative literature of the Jainas appears to get less attention than do the religious, philosophical treatises. Until a systematic study of the various versions of the lives of the Jinas is done and a thorough evaluation of the illustrated manuscripts, painted wall schemes, and loose paintings likewise is conducted, we can only point out some of the consistencies found in the visual evidence which is different from the usual depictions from the lives of the Jinas, based on illustrations from the hundreds of Kalpasūtra manuscripts.

Robert J. Del Bonta has lectured and published on a wide variety of subjects including Jaina art from all over India. He has curated many exhibits at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco (including some on Jaina art) and major exhibitions at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Michigan.

References:

Brown, Norman W., Miniature Painting of the Jaina Kalpasūtra, Smithsonian Instiution, Freer Gallery of Art, Oriental Series No. 2, Washington: Freer, 1934

Cort, John E., "The Jina as King", Vasantagauravam, Essays in Jainism, ed. Jayandra Soni, Mumbai: Vakils, Feffner and Simons Ltd, 2001

Del Bonta, Robert J., "Thoughts on Jain Paintings in San Francisco Bay Area Collections," for Ananda- vana: Essays in Honour of Anand Krishna, Krishna, Naval and Manu, eds., Varanasi: Indica Books, 2004, pp. 211-18.

Del Bonta, Robert J., "Illustrating the Lives of the Jinas: Early Paintings from the Kalpasūtra", Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies, March 2007, Issue 2, pp. 28-31.

Doshi, Saryu, "The Pancha-kalyanaka Pata, School of Aurangabad," Marg 31, No.4, 1978, pp. 45-54.

Doshi, Saryu, Homage to Shravana Belgola, Bombay: Marg Publications, 1981

Doshi, Saryu, Masterpieces of Jain Painting, Bombay: Marg Publications, 1985

Hemacandra Ācārya, Trisastiśalākāpurusacaritra: Vol. I Ādiśvaracaritra, Helen M. Johnson, trans., Gaekwad's Oriental Series, No. LI, Baroda: P. Knight, 1931.

Khandalavala, Karl J. and Moti Chandra, New Documents of Indian Paintinga Reappraisal, Bombay: Prince of Wales Museum, 1969.

Pal, Pratapaditya, ed., The Peaceful Liberators, Jain Art from India, Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art: 1995

Puspadanta Ācārya, Ādipurāna (Sacitra), Mahaviraji: Jainavidya Sansthana, 2004.

Ramachandran, T. N., Tiruparuttikunram and its Temples, Bulletin of the Madras Government Museum, New Series, General Section, Vol. I, Pt. 3, reprinted Chennai: Commissioner of Museums, Government of Tamilnadu, 2002.

(Figure 6) Rājyābhiseka of Rsabha Rajasthan, Amber, circa 1680. Ink, opaque watercolour, and gold on paper. Photo: Del Bonta

It has recently been published in its entirety (Puspadanta 2004) and was discussed by Saryu Doshi in her book Masterpieces of Jain Painting, where a number of images are illustrated.

I had identified the nature of the series to Stephen Markel for the catalogue in Los Angeles. On discussing the series with Saryu Doshi, it was immediately clear to her since she had worked with the impressive pata attributed to Aurangabad. At this time, it is unclear how many folios were in the Amber set. There are no numbers written on any of the folios that I have tracked down. A painting of his mother Marudevī (San Diego Museum of Art 1990.213) makes the identification of the series definite, as do comparisons with the pata.

Although most of the paintings of lustration have a group of crowned Indras performing the lustration with pots, one painting at Tiruparuttikunram has ladies included in the ritual for the child Mahāvīra (Ramacandram 2002: pl. VII, 3). The Palam manuscript also included a woman in an illustration of the lustration of Rsabha (Khandalavala 1969: fig. 148). The inclusion of women suggests the participation of wives of the Indras.

Dr. Robert J. Del Bonta

Dr. Robert J. Del Bonta