The essay was published in Berliner Indologische Studien No. 13/14. 2000, pp. 273-337.

§ 7. The Concept of Type

In connection with Bruhn Gr I, two corrections/additions are necessary. They concern the concept of type (Bruhn Gr I: §§ 2-3, also JID: ch. 22) and the issue of text-image differences (Bruhn Gr I: § 1). See our sections 7-8 (and 6).

Type is not a basic unit like “motif or “motifeme“ in narrative literature. Indian iconography does not consist in a specified (abzählbare) number of comparable units on the type level (Jina, Buddha, etc., Sūrya, Nṛvarāha, etc.). Such a situation would be a great help in the study of the material, but the facts are different.

[A: types] In a way, the types crumble away if they are subjected to rigorous scrutiny. The “Jina type“ does not consist in an even string of 24 Jinas, all more or less related and more or less differentiated: there are special Jinas like Ṛṣabha and Pārśva (to be called “subtypes“?), and there are associated figures like Bāhubali (to be called “related types“?). A type normally consists in a single deity, but there are types consisting of two deities (the Jaina couple) and types which are midway between one-deity types and two-deity types (some cases of gods with consorts).

Furthermore, a type can be understood as a combination of segments, and in that case we have to study the individual segments in combination with the same segments as found with other types (e.g. graha.s on Jina images, and graha.s on images of non-Jinas). An article by G. Mevissen concerning graha.s on Jaina images in stone demonstrates the importance of an individual segment (Mevissen Pl: figs. 1-6: Jina images). The term “segment“ is more or less identical with “partial motif (Bruhn Gr I: § 4), but in the present context we prefer “segment“. The study of segments is often difficult because close-ups are not published. A third problem concerns the images which are not found in the texts. If they have an identity of their own (“art types“ like the Jaina couple), there will be no difficulty. But if they are ad hoc creations (such as many attendant deities of the “fuzzy period“) they do not fit into a corpus of types. [End of TYPES.]

[B: other developments] In spite of all the complexities, we can understand Indian iconography as consisting mainly in well-defined types. Different types may be different as types (structure, etc.), but all types are well-defined or fairly well-defined units. The same is not true of clusters and series of female goddesses. We mention “goddess with child“, “Avalokiteśvara“, “Viśvarūpa“ and “Gajāsurasaṃhāra (cum Andhakāsuravadha, etc.)“ as instances of clusters. More often than not the cluster creation is due to the parallelism of male and female (Varāha and Varāhī) and to the existence of a type in different contexts (Vaiṣṇavī, yakṣī Cakreśvarī, mahāvidyā Cakreśvarī). Clusters may but need not consist in a specified number of types. Generally speaking, they differ in extent and structure; but there is a degree of unity so that a common term (“cluster“) seems to be justified. Instances of series are the sixty-four yoginīs, the sixteen mahāvidyās and the pañcarakṣās. The basic problem in the study of series is probably the isolation of some well-defined types within the series. [End of A-B.]

As the basis for the study of types we introduce the concept of an “inventory“. The inventory is different from the meager descriptive pattern of the śilpa texts consisting mainly of the well-known standard data: name of the deity, designation of his or her vāhana, number of heads and hand-attributes. These minimum data are exhaustive in some cases, but in the majority of cases, they depict only some facets of the images.

Preparing an inventory, as we understand it, means describing all features of the images of a given type (aṣṭa prātihārya.s, etc. in the case of the Jina). This must be linked to strategies of reduction. If we describe a particular class of Jinas (e.g. Western Indian Jina images in bronze) we have to isolate the standard. We do not describe each and every Jina image of the class in toto but only those features of the individual images which are additions to or deviations from the standard. The class may be made more or less comprehensive, however. If we concentrate for example on pre-1050 bronze Jinas (Western India), the standard will be “Jina without cihna“, “attendant deities: K-and-A“, etc. Later on, the situation changes, and a new standard (new standards?) must be fixed.

Moreover, we are not only concerned with normal descriptions, but also with theoretical considerations (§ 1): What does the Jina look like? What is the difference between a Jina and a Buddha, etc.? Apparently simple questions become complex, and this indicates the need for descriptive methods. For the general description of the Jina (“All-India Jina“) we need several inventories (Western Indian bronze Jinas before A.D. 1050, Western Indian Jinas after A.D. 1050, etc.). In theoretical language, an inventory (a set of inventories) paves the way to a model of the type being a reproduction of the type in reduced form.

There will be vast differences, for example, between the internal structure of the description of Ambikās and Jinas. Even then something like a general grammar for the creation of inventories of the types can be proposed. We can, for example, use fundamental classificatory categories, which are often dichotomous. In addition to points mentioned already in connection with Jaina deities (number of arms, seated and standing posture) we refer to two categories connected with the Jina type: multiple Jinas vs. single Jinas, and Pārśvas vs. non-Pārśvas. Some differences are important without being numerous: Kamaṭha's attack against Pārśva (JRM: frontispiece) vs. ordinary Pārśvas. There is also the difference between standing and seated Jinas. This is, however, not an important difference per se. It is a difference which is interesting because it may imply other differences, stylistic and iconographic.

Many differences are important without being fundamental. In the case of Pārśva images we have representations with conventional companions (two male cāmara-bearers) and with unconventional companions (Nagar Wo: pl. 65; JID: fig. 38). Ṛṣabha's hair-dress is linked with problems of identification and with problems of morphological description (§ 1). Naturally, there is a regressus from fundamental to medium and minor differences. We have mentioned the problem already in the previous section.

“Styles“ are not automatically relevant to our discussion. Minor stylistic developments can be ignored, while major developments require increased attention. We already suggested a dichotomous division for the Western Indian Jina images. In the case of “Deogarh“ we have to distinguish between early-medieval (Gwalior, Deogarh and a few other places) and medieval (Central India and adjoining areas) images. A division may also be useful in the case of Karnataka (“Śāntara period“ vs. Hoysaḷa period).

The term “basic variable“ (§ 6) is less general than the term “fundamental classificatory category“. It recommends itself mainly in the description of frequent and settled types (more particularly of gods and goddesses).

We attach special importance to the fundamental classificatory categories because there is the deficit in the case of the general sections of many descriptions. We get, for example, nowhere information about the distribution of tritīrthika.s. To give reliable information on this point is of course difficult, if the situation is to be described for Jina iconography in general. We have images with three Jinas, four Jinas, etc. (supra). The question of distribution arises in all these cases: where do we find tritīrthika.s, where chaumukha.s, and so on.

The usefulness of the study of fundamental classificatory categories is also demonstrated by a cluster like the goddess with child. In order to disentangle the material (prior to a study of types), we have to distinguish: between “female alone“, “female and male“ and “female in a series“; between two-armed and many-armed goddesses; between “goddess in arms“ and “goddess without arms“; between “mother with child alone“ and “mother with child and lion“; between “Jaina“, “Hindu“, “Buddhist“ and “religion unclear“.

In the description of types, it is not absolutely necessary to draw a clear-cut line of demarcation between fundamental (major) and non-fundamental (minor) differences (categories). What matters are the sharp dividing lines as such. The detection of such dividing lines, or rather the decision to accentuate them, is often a matter of discretion, but it is essential to the description of a type (regional or general). Differences not connected with sharp dividing lines belong often to the border area between iconography and style, whereas well-defined differences, however small (e.g. differences in Ṛṣabha's hair-dress: our last example), deserve attention at least in more analytic studies.

The last element in the description of types is the attribute issue. We introduce the concept of attribute because there may be questions of the following type: “are lion-throne, triple parasol roof, male cāmara-bearers, etc. attributes of the Jina?“. It is,

however, better not to use the term “attribute“ (being mainly connected with the iconography of Christian saints), but rather to use the following scheme in order to describe the situation.

[ I ]:

“Element so-&-so is always, almost always, rarely, almost never found with type (x)“.

[ II 1 ]:

“Element so-&-so is only found with type (x)“.

[ II 2 ]:

“Element so-&-so is occasionally, frequently, regularly found with other types than (x) as well“.

The answer to these questions requires of course the availability of several inventories, i.e. a complete set of inventories, for each type (x, y, etc.).

The actual terminology depends on the individual case. We use the term “hand-attribute“ simply in the sense of “object held in and gesture displayed by the hand“. There can also not be any objection against the term “attribute value“. If an element is mainly found with a particular type (e.g. triple parasol and male cāmara-bearers in the case of the Jina), the attribute value is high, in the opposite case (lion-throne of the Jina) it is low.

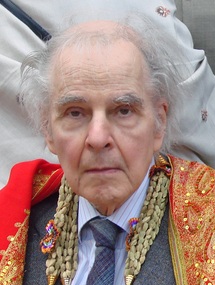

Prof. Dr. Klaus Bruhn

Prof. Dr. Klaus Bruhn