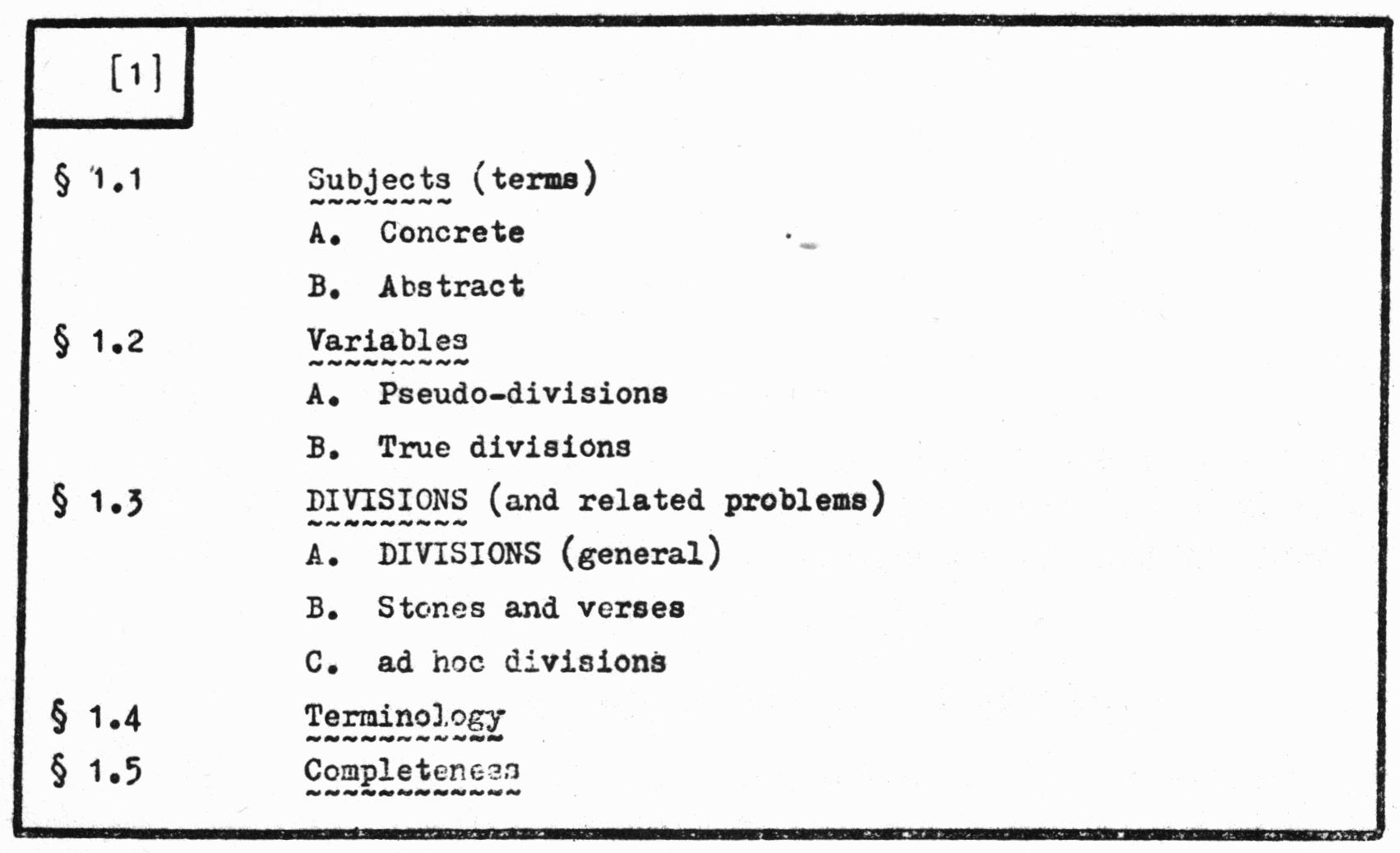

The paper was published in the volume German Scholars on India - Contributions to Indian Studies Vol. II, Bombay: Nachiketa Publications Limited, 1976, pp. 26-50.

Classification in Indian Iconography

While going through the pages that follow, the reader will not only experience the general difficulties caused by all discussions of an abstract nature. He will also be faced with a more basic problem. The reader may ask whether concepts - as they are supplied, discussed and analysed in the present article - are really instrumental to research or merely reflect the meandering thoughts of a theorist. On a previous occasion we have already emphasized that highly technical concepts are in other disciplines part and parcel of research. Here we would like to add that in certain areas of Indian iconography (e.g. in the case of "blurred" iconographic programmes found in compositions with miniature figures and elsewhere) the conventional tools of research - identification etc. - are not sufficient. Starting from this consideration, we can go one step further and ask whether present research pays equal attention to all parts and aspects of Indian iconography. This is hardly the case. As a rule, figures with literary background take precedence over figures without it, clear iconographic programmes over unsystematic programmes, the "great" gods and goddesses over the minor members of the pantheon, gods carrying such and such attributes over attributes belonging to such and such gods. To this limitation in scope corresponds the limited theoretical apparatus. Therefore, widening of the scope would imply the employment of new tools of research - and vice versa. We hope we shall succeed at last to some extent in making this statement plausible.

Previous studies have paved the way for the present contribution. They were published between 1956 and 1976 (Khajurāho, Distinction, Deogarh, Repetition, Pārśvanātha; bibliographical details in § 4). The article as such emerged from a study of specialized problems in the field concerned, but later on the emphasis shifted from the material to the method. The pictorial presentation is kept to a minimum. The reader will, however, find rich photographic material in a study on Kṛṣṇa iconography published recently by U. P. Shah (Baroda). Besides, the author would like to emphasize already at this stage that photographs liberally supplied by colleagues (only a few could be published here) helped to lay the foundations of the article. The acknowledgements will be found in § 4, and an explanation of terms is given in § 6.

§ 1. Classification in General

§ 1.1 Subjects

A glance at the index of a book will show that the terms indexed differ in their character, or to be more precise, that they differ as terms. In the case of Indian iconography, we would say that names of gods (Śiva, Lakṣmī etc.) are concrete, while terms like "syncretism", "multiplication of limbs" are abstract. In the case of a book on caste, the distinction between names of castes (Brahmin, Kayasth etc.) and structural features (endogamy, commensality etc.) would supply an analogy if not a parallel. Studies in Indian iconography employ abstract terms but rarely. To demonstrate this and to bring out the difference more clearly we shall supply a few more examples. The number of concrete terms is of course almost unlimited: Members of the pantheon (Śiva, Lakṣmī, Buddha, …), objects carried in the hands (lotus, trident, disk …), mudrās or gestures of the hands (abhaya, varada, vyākhyāna …), figures without individual names (garland bearers, chowry bearers, vyālis...), special compositions (caturmukhaliṅga, tritīrthika, pāduka …) Abstract terms, on the other hand, are rare and mostly restricted to the vocabulary of individual authors:

The term "Vaiṣṇava iconography" is more general than "Viṣṇu iconography". Similarly "attribute" is more general than "hand-attribute". This difference crosses that between concrete and abstract. The movement from the general to the particular is present in any classificatory operation.

Again the character of classifications seems to be the same in the case of concrete and in the case of abstract subjects, although the latter belong to the sphere of concepts and are not available from the beginning.

§ 1.2 Variables

Variables are a simple method of organizing information, and forms to be completed are amongst the best known examples (male/female; age; children/no children). But strictly speaking such elements are not only common, they are omnipresent. Scientific nomenclature bears ample testimony to this (singular/plural in grammar, monotheism/polytheism in the history of religions). Consequently it is only the problem of systematic employment that deserves our attention. It is obvious that Indian iconography should pay attention to the varying numbers of heads and arms, but the systematic distinction between the three-headed deity and the four-headed deity is a different matter. - Like many formal discussions, observations on the subject of variables can only be introduced by recalling a few commonplaces. A variable has two or more values (children/no children; age). Completeness is normally essential, and this can be secured by yes-or-no statements (children/no children), by a category "other cases", or by complete enumeration of all the individual cases. The nomenclature may be based on the variable (age), on the values (children/no children), or optionally on both (married/ unmarried, marital status). The subject (Śiva etc., syncretism etc.) presents no problems.

The variable concerns points of detail (e.g. colour of the eyes) or complex features (e.g. colour in the racial sense). A fairly analogous distinction in iconography would be that between two-four-(six etc.) arms on the one hand and Hindu-Buddhist-(Jaina etc.) deities on the other. We shall use in both cases the term "division" qualified by the attributes "pseudo-" and "true" respectively. A pseudo-division is just a value in the sense described above, whereas a true division (Hindu-Buddhist-Jaina etc., Viṣṇu-Śiva-Lakṣmī etc.) combines several features. It seemed, however, practical to bring all sorts of divisions together (there are border-line cases like the "three headed deity") and to place special emphasis on the concept of variable, more particularly on variables producing pseudo-divisions. Pseudo-divisions are, on the one hand, an "Ersatz" for true divisions (i.e. classes) whenever lack of concomitance makes it impossible to arrange the material in well-defined compartments (see § 3). On the other hand, they serve some special purposes. Two cases ("crossing oppositions" and "description through transformation") shall be discussed now (pp. 29-30).

Terms like "narrative panels" on the one hand and "images", "iconoplastic art" on the other suggest that we have two well distinguished types of representation: one more dynamic and emphasizing individual incidents, one more static and showing a god or goddess under a more general aspect. As soon as pseudo-divisions are employed, the language becomes clearer; the single opposition is replaced by a group of oppositions and it is seen (in most cases) that these oppositions are crossing. That a panel shows more than one episode (or more than one phase of an episode) does not mean that the representation is full of life and truly narrative; that a panel shows but one episode does not mean that it is stiff. We find panels with several episodes, each following a conventional pattern. They may almost take the shape of ideograms and appear on the slab like different punches on a coin. By contrast, a panel showing a single episode may be full of life and it may depict a specific event in a convincing manner. In the abstract language required for pseudo-divisions we have to employ expressions of the following type: panel showing one episode/panel showing two or more episodes; rendering spirited/stiff; formula conventional/untypical. See also § 3.

"Description through transformation" divides an iconographic statement (i.e. a sentence) into a number of units in order to replace certain units by others. Below we give examples for the division as such, assigning identical numbers to corresponding units (i.e. to the values belonging to the same variable): -

A demonstration of the process as such is given below. We have selected a problem from Jina iconography: the confusion arising from the artists' inconsistent employment of the attribute "strands", which distinguishes in theory the Jina Ṛṣabha (No. 1 in the series of the 24 Jinas) from the remaining 23 members of the series (compare Deogarh, § 265). It would appear that a precise description of the facts is best achieved through the following transformation: -

In each of the four cases, one or more formulas may be available. The best-known formula for the treatment of the hair are the curls which form the typical hair-dress of the Buddha.

Prof. Dr. Klaus Bruhn

Prof. Dr. Klaus Bruhn