We begin with the namaskar mantra. This utterance, also known as the mahamantra or the navkar mantra, is Jainism's universal prayer and all-purpose ritual formula. It is hardly possible to exaggerate its importance. It is repeated on most ritual occasions, and many Jains believe it to contain an inherent power which, among other things, can protect the utterer in times of danger. When, in the summer of 1986, I arrived in Ahmedabad to study Jain rituals, a Jain friend who was assisting me in my research insisted that my first order of business should be to commit the namaskar mantra to memory. One of my most pleasant memories of Jaipur is of an elderly friend pointing with pride to his small grandson who, hardly yet able to talk, had memorized the mantra. A somewhat more disquieting memory is of yet another friend who responded to an allusion to my own nonvegetarian background by hastily mumbling the mantra under his breath.

In essence it is a salutation (namaskar) to entities known as the five paramesthin's, the five supreme deities.[1] These beings are worthy of worship, and it is crucial to note that these are the only entities the tradition deems fully worthy of worship. They are, in order, the arhat's ("worthy ones" who have attained omniscience; the Tirthankars), the siddha's (the liberated), the acarya's (ascetic leaders), the upadhyayas's (ascetic preceptors), and the sadhus (ordinary ascetics). The mantra 's importance to us is that it is a charter for a type of ritual, singling out a certain class of beings as proper objects of worship. These beings, we see, are all ascetics.[2] This is the fundamental matter: Jains worship ascetics, and this is the most important single fact about Jain ritual culture.

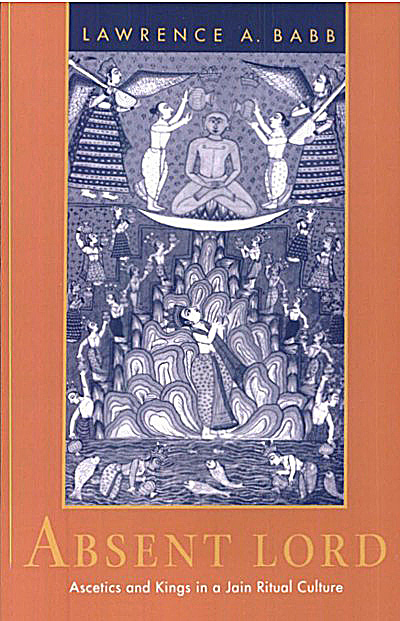

This chapter deals with ascetics as objects of worship among the Jains. Who are they? What qualities single them out from other beings? What makes them worthy of worship? We begin addressing these questions by examining the text of an important ritual. The namaskar mantra lists the arhat's, by which is meant the Tirthankars, as foremost among those who are worthy of worship. The ritual with which this chapter begins is itself an example of Tirthankar-worship. Its text, moreover, tells us something of why the Tirthankar is worthy of worship. After examining this rite, we will consider ideas about the cosmos that inform the rite, and move finally to a discussion of living ascetics as objects of worship.

The full namaskar mantra is as follows (from P.S. Jaini's translation; 1979: 162-63):

I bow before the worthy ones [arhat] - the Jinas;

I bow before the Perfected beings [siddha] - those who have attained moksa;

I bow before the [mendicant] leaders [acarya] of the Jaina order;

I bow before the [mendicant] preceptors [upadhyaya]

I bow before all the [Jaina] mendicants [sadhu] in the world

This fivefold salutation, which destroys all sin, is preeminent as the most auspicious of auspicious things.

I use the term ascetic (or mendicant) to refer to individuals who have taken initiation (diksa) as full-time world renouncers. It should be understood, however, that lay Jains also engage in ascetic practices, and it is believed that lay Jains can even - in rare cases - achieve liberation directly from the householder state. I use the terms monk and nun to refer to male and female ascetics (sadhu s and sadhvi s).

Prof. Dr. Lawrence A. Babb

Prof. Dr. Lawrence A. Babb