It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of the fourteen dreams that visit the mother of a Tirthankar-to-be. In accounts of the Tirthankar's conception and birth they are almost always enumerated. They are ritually dramatized during Paryusan, the most sacred occasion of the year. They are also reiterated in the snatra puja and in many other rites. Why are these dreams described and enacted so often? I suggest that it is because they reach to the values and choices that lie at the very heart of the Jain tradition's vision of the soul's opportunities and destiny.

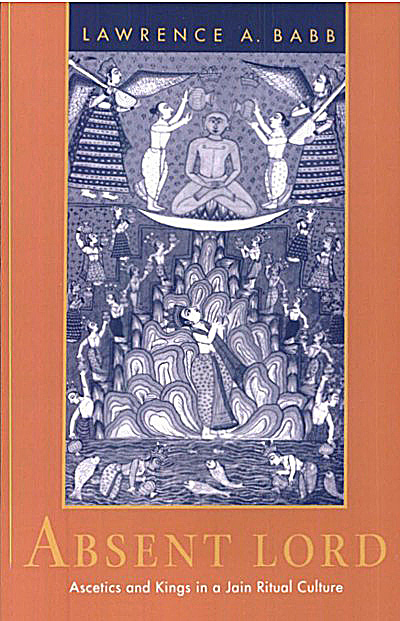

As we saw in the last chapter, the dreams have a double meaning: They are the dreams that announce the birth of a universal emperor, but they also announce the birth of a Tirthankar. In other words, a Tirthankar is one who might have been an earthly king but became an ascetic instead[1] In this connection it is important to note that a Tirthankar-to-be is always born into a family belonging to the Ksatriya varna, the social class of warriors and kings (P. S. Jaini 1985: 84-85). Put otherwise, the Tirthankar renounces earthly kingship to become a spiritual king. Kingly martial valor is transposed to a transcendental plane; instead of victory over earthly sovereigns, the Tirthankar becomes a "victor" (jina) over attachments and aversions. Asceticism thus turns out to be a spiritualized martial virtue.

The Tirthankar's spiritual kingship is the highest manifestation of the ascetic path. Others, however, prosper in the world and use their worldly wealth and power to serve ascetics - and by implication, those who serve ascetics prosper in the world. Earthly kingship, rejected by the Tirthankar, is the highest manifestation of this path, which is dramatized by the heavenly projections of earthly kingship, the Indras and Indranis who are the kings and queens of the gods. It is, as well, the path of nonascetic Jains, who, as worshipers, identify with the kings and queens of heaven. Having renounced earthly kingship, the Tirthankar becomes a king of the spirit who is worshiped by kings, both heavenly and earthly.

Those who inhabit human bodies find themselves at the crossing point of these two paths. Unlike the gods, humans can be ascetics. However, as we noted in the last chapter, those who take ascetic vows cannot (as do the gods) worship with material things; being possession-less, they have nothing to offer.[2] Indeed, we now see that there is an even more basic impediment to ascetics worshiping with material things. There is a fundamental resonance between the role of the worshiper and heavenly/earthly enjoyment as embodied by the gods and goddesses. To worship with material things is to step into this paradigm, which is seemingly inconsistent with the ascetic ideal. Lay Jains, on the other hand, are in a perpetual condition of being able to choose. They can worship with material things, but they can also engage in various forms of asceticism, especially fasting, for which lay Jain life is justly famed. It might be said that for pious lay Jains life is, in effect, a constant oscillation between these two modes of praxis.

The ascetic practices of lay Svetambar Jains have been well described by Cort for Gujarat (1989: Ch. 5) and Laidlaw for Rajasthan and Jaipur (1995: Part III). As both authors show, asceticism does not radically divide ascetics under permanent vows from the laity. Although lay ascetic practice is formally conducted under the aegis of ascetics (who administer the vow that is required for an ascetic practice to be efficacious), asceticism is a central feature of lay Jain life. In both regions the principal lay ascetic practices are the same. There is, first, the practice known as samayik, which is a forty-eight-minute period of meditation.[21] Lay Jains who perform samayik typically do so after visiting the temple in the morning. An extended version of samayik is posadh in which a layperson in effect becomes a mendicant for a period of twelve or twenty-four hours. Another important ascetic practice is pratikraman, an arduous and complex rite of confession and expiation of the performer's sins.[3] It is required of mendicants in the morning and evening. Only the most serious lay Jains perform it frequently, but virtually all Jains perform it once per year during the holy period of Paryusan.

Undoubtedly, however, fasting (upvas) is the mode of austerity that Jains have most brought to a high art. Food is an essential part of the body's karmic imprisonment, and obviously, therefore, the attenuation of eating - tending toward cessation - is necessarily among the tradition's most valued modes of praxis. The Jains have elaborate taxonomies of fasting based on length of time and types of consumption allowed or forbidden. The tradition's admiration for fasting is indicated by the fact that successful fasters are often felicitated in public ceremonies. It is certainly not the case that most lay Jains are serious fasters. Most of my male friends in Jaipur did little of this sort of thing apart from the bare minimum at the time of Paryusan. As is the case in the surrounding Hindu world, among Jains lay austerities are practiced mainly by women, especially older women, and by men in retirement. It is, however, the case that the ideal of asceticism - as expressed in fasting and other types of ascetic performances - casts a kind of cool light over Jain life in general. Austerity and renunciation are the tradition's highest values, and even those whose styles of life are far from austere know that they should be pursuing these values.

While the centrality of asceticism stems from the fact that ascetic practice directly causes the eradication of karma, asceticism also brings about good worldly results; that is, it brings prosperity in the here and now and favorable rebirth.[4] Put somewhat differently, it is associated with merit (punya) as well as karmic removal (nirjara). And, as always, the key issue is the bhav - the "spirit" - in which austerity is conducted. It should be conducted in the spirit of true nonattachment. If it is, as Laidlaw points out, then good fortune can enter the situation by the back door; the faster's undesire for good results is somehow essential to bringing them about (1995: Ch. 10). Here, as in so many areas of Jain life, we find ourselves in the presence of an ambiguous double-ness.

Living ascetics, however, do indeed engage in worship in a more general sense. They can perform bhav puja and can also participate in congregational worship as observers and singers. But dravya puja is barred.

Prof. Dr. Lawrence A. Babb

Prof. Dr. Lawrence A. Babb