2

Early Jainism in Tamilnadu - New Epigraphic Evidence

The decipherment of cave inscriptions in Tamilnadu has produced new evidence proving conclusively the association of Jainism with the caves. There are no vestiges of Buddhist or Ājīvika occupation of the caves. The hitherto unsuspected influence of old Kannada on the language of the cave inscriptions from the earliest period has shown that Jainism reached the Tamil country through Karnataka at a very early date not later than about the third century B.C.. This paper is a brief summary of the new epigraphic evidence which has been presented in detail in my book Early Tamil Epigraphy (2003).[1]

To the earlier investigators of the Tamil caves, the Brāhmī inscriptions in characters resembling those of the Asokan edicts suggested Buddhist association even before the inscriptions could be properly understood. However, the texts of the Tamil-Brāhmī inscriptions, which have now been fully deciphered, do not reveal any internal evidence for associating the Buddhist faith with the Tamil caves.

Early phase of Jainism in the Tamil country

Bhadrabahu-Chandragupta legend

The advent of Jainism in South India is traditionally traced to the migration of Chandragupta Maurya and his preceptor Bhadrabahu to Sravanabelagola in Karnataka. According to the legend, when foretold of a terrible famine in Magadha, which would last twelve years, the Jaina Saṃgha led by Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta migrated to South India and settled down at Sravanabelagola. Viśākha Muni, the disciple of Bhadrabahu, went further south to the Tamil country and preached in the Cōḷa and Pāṇṭiya kingdoms. As the Bhadrabahu-Chandragupta legend is found only in relatively late sources, scholars have been hesitant to accept it as a historical event. The Tamil-Brāhmī cave inscriptions, now known to be the earliest Jaina records in South India, provide indirect corroboration of two key elements of the legend. The palaeography of the cave inscriptions is consistent with borrowing from Magadha in ca. 3rd century B.C. during the Mauryan Age. The decipherment of the inscriptions has also revealed early links with Karnataka and Old Kannada indicative of the proximate source of Jainism in the Tamil country. The views of some scholars that Jainism reached the Tamil country from Bengal and Orissa and not from Karnataka can no longer be accepted.

Samprati and Jainism in the Tamil country

Dasaratha and Samprati, grandsons of Asoka, succeeded him and ruled simultaneously from Pataliputra and Ujjain respectively. While Dasaratha seems to have supported the Ājīvika faith, Samprati became an ardent supporter of Jainism under the guidance of his preceptor Suhastin. Samprati despatched Jaina missionaries to various regions in South India including the Damila (Tamil) country. Jaina literary evidence credits the spread of Jainism from Ujjain to the Deccan and other southern countries.

Jaina terminology

Some of the key words in the inscriptions which help us to have a glimpse of the early phase of Jainism in the Tamil country are discussed below.

Titles of monks

kaṇi

The expression kaṇi (Pkt. gaṇi < Skt. gaṇin) 'a senior Jaina monk, the head of a gaṇa' occurs four times at Mangulam (ca. 2nd century B.C.) and twice at Alagarmalai (ca. 1st century B.C.). While many terms like ācārya, etc., are common to the Brahmanical, Buddhist and Jaina religions, the expression gaṇin is peculiar to Jaina hierarchy. Thus, the occurrence of this term in Early Tamil-Brāhmī inscriptions is conclusive evidence of the occupation of the caves by monks of the Jaina faith. We learn from the Mangulam inscriptions that Kaṇi Nanta-siri (Gaṇi Nanda-śrī) was the senior Jaina monk who received the endowments of three hermitages from the kinsmen, vassals or officers of Neṭuñceḷiyaṉ, the reigning Pāṇṭiya king. The inscriptions bear testimony to the support that the Jaina faith received from the Pāṇṭiya king, his court and the local merchant guild (nikama < nigama) at this early period. The given name or clan name of the senior Jaina monk was Kuvaṉ, revealing his Tamil origin. This is a significant fact. For, if a native Tamil ascetic could have risen in the Jaina monastic hierarchy to occupy the position of a gaṇi ('head of a gaṇa') at this time, then Jainism must have taken root in the Tamil country much earlier, that is, not later than the earlier half of the 3rd century B.C.

amaṇaṉ

The expression is derived from Ta. camaṇa < Pkt. samaṇa < Skt. śramaṇa 'an ascetic or monk of non-Vedic religions (Ājīvika, Buddhist or Jaina)’. However, in the Tamil tradition, the term is exclusively applied to the Jaina monks indicating that the Jaina samaṇa monks reached the Tamil country earlier and that the Buddhist monks who came later had to be given other appellations like cākkiyar, tērar, puttar, etc., to distinguish them from the Jaina ascetics. The term amaṇaṉ occurs first at Mettuppatti (ca. 2nd century B.C.). This inscription records the gift of Utayaṉaṉ (Udayana) to Attiraṉ, the Jaina monk from Matirai (Madurai). The occurrence of the word in a Tamil-Brāhmī inscription of the 2nd century B.C. proves that Jainism had spread to the Tamil country before that date. The linguistic testimony furnished by this word goes further. The use of the evolved form amaṇaṉ (formed by the loss of the initial c in camaṇaṉ) shows that the word must have been borrowed into Tamil much earlier to allow sufficient time for the linguistic assimilation and evolution samaṇa > camaṇa > amaṇa. On the basis of this evidence, we may date the spread of Jainism to the Tamil country at least to the 3rd century B.C., if not earlier. The variant form amaṇṇaṉ occurs in two later inscriptions from Pugalur (ca. 2nd century A.D.). The inscriptions record the construction of a rock shelter for Ceṅkāyapaṉ, a senior Jaina monk, by King Ātaṉ Cel Irumpoṟai to mark the occasion of the investiture of his grandson as the heir apparent (iḻaṅkō). The Pugalur inscriptions (ca. 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D.) attest to the support of Jainism by the Cēra king, his court and by the merchant community.

upacaṉ

The expressions upacaṉ at Tiruvadavur and its variant form upaca-aṉ at Kilavalavu and Kongarpuliyankulam dated to ca. 2nd century B.C. are derived from Skt. upādhyāya 'spiritual teacher' through Pkt. upajhaya, uvajha, etc.; cf. Ka. uvajjar and Ta. uvaccaṉ 'teacher'. The upādhyāya is venerated as one of the Pañcaparamēṣṭhin (along with Arhat, Siddha, Ācārya and Muni) by the Jainas. In the Tamil Jaina tradition, the upādhyāya is a lay teacher of scriptures. He functions as the priest in the local Jaina temple and also conducts religious ceremonies in Jaina households. In course of time, with the waning of Jaina influence in the Tamil country, the Uvaccar became priests in the shrines of piṭāri (< bhaṭāri, originally Jaina) and other village goddesses. Still later, they figure as temple-drummers, dance-masters and musicians in medieval inscriptions.

patantaṉ

The expression patantaṉ occurs as the title of a Jaina monk at Anaimalai (ca. 2nd century A.D.). It corresponds to Pkt. bhadanta 'venerable, reverend'. A variant form bhadata occurs as the title of a Jaina monk in an early Prakrit inscription from Mathura. The variant forms bhadaṃta and bhayaṃta are attested in Jaina Prakrit works.

att(a)vāyi

The expression attuvāyi in the Anaimalai inscription (ca. 2nd century A.D.) appears to be a title as it is prefixed to a personal name, most probably that of a Jaina monk. The word is probably to be read as attavāyi; the scribal error appears to be due to stress on the first syllable in the original Prakrit. The first part of the name is from Pkt. attha < Skt. artha 'meaning', and the second part from Pkt. vāyi < Skt. vācin / vādin ' one who reads / expounds'. The whole expression attavāyi may be interpreted as 'one who expounds the meaning (of scriptures) ‘; cf. AMg. atthavāya 'disputation of meaning' (PSM); vācaka / vāyaka ' preacher' occurring in Prakrit inscriptions.

ācāriyar

The expression ācāriyar and the variant form ācirikaru < Skt. ācārya 'preceptor' occur as the titles of senior Jaina monks in the Early Vaṭṭeḷuttu inscriptions at Paraiyanpattu and Tirunatharkunru respectively (ca. 6th century A.D.). In the Jaina monastic tradition, especially the Digambara, ācārya is a title accorded to very senior monks who are considered to be superior to the upādhyāya in the list of the Five Dignitaries (pañca-paramēṣṭhin) worshipped daily by the Jainas.

māṇākkar

The term literally means 'student' (honorific singular), but occurs at Paraiyanpattu

(ca. 6th century A.D.) as a Jaina technical term with the specialised meaning of 'acolyte or disciple' of a senior Jaina monk. In later Jaina inscriptions as at Kalugumalai (Tirunelveli District), the expressions māṇākkar (masc.) and māṇākkiyar (fem.) occur in this sense.

Titles of nuns

pa(m)mitti

The expression pa(m)mitti occurs at Alagarmalai (ca. 1st century B.C.) as the title of a Jaina nun named Sapamitā (from Pkt. sappamittā < Skt. sarpamitrā). The term pammi-tti appears to be the feminine gender form of pammaṉ (masc.) 'Jaina novice'. The expressions are ultimately derived from Pkt. bamma < Skt. brahma / brāhmī.

kanti

Cē-k-kant(i)-aṇṇi and Cē-k-kanti, mother and daughter, figure in the inscription at Nekanurpatti (ca. 4th century A.D.). Both are Jaina nuns as may be seen from the suffixed title kanti. The term kanti is attested as a personal name or title of Jaina nuns in Tamil literary works. The variant form kavunti occurs as the personal name of a senior Jaina nun. The term kanti (variants khanti, ganti) occurs in Kannada inscriptions as an affix to the personal names of Jaina nuns. The expression is probably derived from gaṃṭhi (AMg.) 'one who composes a literary work' (PSM) < grantha (Skt.) 'book'.

Common religious terms in Tamil-Brāhmī and Early Vaṭṭeḷuttu inscriptions

Some of the expressions in the Tamil-Brāhmī and Early Vaṭṭeḷuttu inscriptions are common to Vedic (Brahmanical) Hinduism and non-Vedic faiths (Ājīvika, Buddhist and Jaina). They have been treated in the present study as relating to Jainism taking the overall context into account.

atiṭṭāṉam: 'seat, permanent fixed abode'; refers to stone beds in the cave shelters.

aṟam : 'charity, religious life'.

uṟai, uṟaiyuḻ : 'abode of ascetics'.

tāṉa: 'religious gift'.

namōttu: 'Let there be salutation!'; an invocation.

paḻḻi: 'hermitage'; refers to the cave-shelter.

dhammam, dhamam : 'religious gift, charity or endowment'.

Jaina religious terms in Early Vaṭṭeḷuttu inscriptions

Religious terms specific to Jainism or with specialised meanings in the Jaina context occur in the nicītikai inscriptions in Early Vaṭṭeḷuttu at Paraiyanpattu and Tirunatharkunru (ca. 6th century A.D.). The expressions are listed below in alphabetical order with meanings.

aṉacaṉam: 'abstinence from food'; the Jaina religious penance of fasting unto death.

ārātaṉi: 'worship'; a Jaina technical term for the religious penance of fasting unto death.

nicītikai: 'seat of penance' (for fasting unto death).

nōṟṟa, nōṟṟu: 'who observed / having observed penance'. In Jaina terminology, nōṟṟal or nōṉpu refer to religious fasting.

muṭitta : 'who completed'; a Jaina technical term for ending one's life through the

penance of fasting unto death.

Evolution of Early Jainism in the Tamil country

Based on the distribution, frequency and contents of the Jaina inscriptions in Tamil-Brāhmī and Early Vaṭṭeḷuttu, it is possible to discern three distinct stages in the evolution of early Jainism in the Tamil country.

Early period (ca. 3-1 centuries B.C.)

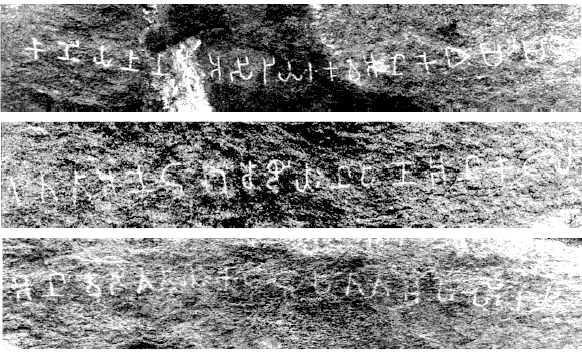

The earliest Jaina inscriptions in the Tamil country are found in the Pāṇṭiya region with most of them clustered around Madurai. The palaeographic evidence indicates that Jainism must have arrived in the Pāṇṭiya country not later than the 3rd century B.C. The new faith received active support from the Pāṇṭiya dynasty and the local merchant communities as indicated by the inscriptions at Mangulam (ca. 2nd century B.C.) and Alagarmalai (ca. 1st century. B.C.). The presence of Old Kannada expressions and personal names in the cave inscriptions, especially at Sittannavasal (ca.1st century. B.C.), points to Karnataka as the route through which Jainism reached the Tamil country. It is also likely that the Tamil-Brāhmī script was adapted from the Mauryan Brāhmī in the Jaina monasteries (paḻḻi) of the Madurai region some time before the end of the 3rd century B.C. as the earliest cave inscriptions are dated to about the beginning of the 2nd century B.C. It appears from the absence of reference to sects that the early lithic records in the Tamil caves belong to the period before the schism between the Digambara and Śvētāmbara sects. It is arguable from palaeographic evidence that the Early Tamil-Brāhmī cave inscriptions are the earliest lithic records of the Jaina faith in India, as the Mangulam inscriptions of the time of Neṭuñceḷiyaṉ (Plate 2.1) appear to be earlier than the Jaina Prakrit inscriptions at Mathura and those of Kharavela of Kalinga.

Middle period (ca. 1-3 centuries A.D.)

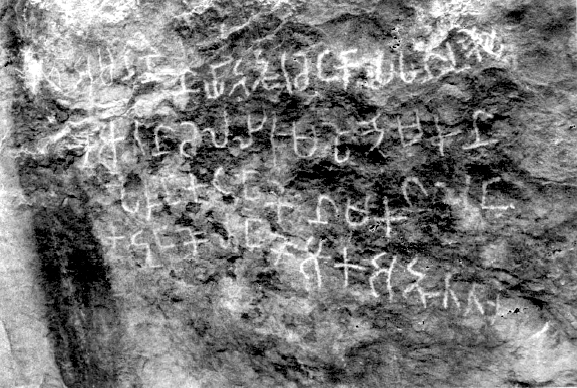

There is a sharp fall in the total number of cave inscriptions in this period. The centre of Jainism in the Tamil country appears to have shifted from the Pāṇṭiya to the Cēra region in the early centuries A.D., as indicated by the sharp fall in the number of inscriptions in the Pāṇṭiya country and the equally sharp rise in their number in the Cēra country during this period. As in the Pāṇṭiya country in the earlier period, Jainism was patronised by kings, and local merchant communities in the Cēra country also, as seen from the Pugalur inscriptions of ca. 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D. (Plate 2.2). Contacts with the Jaina community in Karnataka continued in this period also, as indicated by what appear to be Kannada personal names in the inscription at Tirupparankunram (ca. 1st century A.D.). The earliest literary evidence of Jainism in the Tamil country belongs to this period; There is also literary evidence from the Caṅkam poems that Jaina monasteries (paḻḻi) existed in cities like Kāviri-p-pūm-paṭṭiṉam and Madurai even during the early centuries A.D..

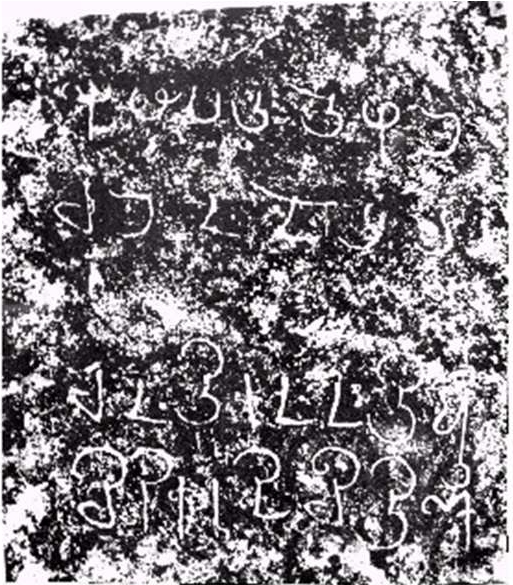

Late period (ca. 4th - 6th centuries A.D.)

The era of natural cave shelters came to an end during this period. The Early Vaṭṭeḷuttu inscriptions at Sittannavasal and Tiruchirapalli (ca. 5th century A.D.) are the last of the Jaina cave shelters in the earlier tradition. A new type of Jaina monuments appears in the Tamil country in the 6th century A.D. in the form of the nicītikai inscriptions at Paraiyanpattu and Tirunatharkunru (Plate 2.3). These are epitaphs engraved on the bare summit of boulders commemorating the places where Jaina ascetics fasted unto death. Even though these Early Vaṭṭeḷuttu inscriptions are earlier in date, they clearly belong to the sallekhanā ('religious fasting unto death') tradition of Karnataka, which has more numerous examples than the Tamil country. The nicītikai inscriptions represent a fresh wave of influence from Karnataka, though contacts between the Tamil and Kannada Jaina communities existed even earlier in this period as indicated by the inscription at Nekanurpatti (ca. 4th century A.D.). During most of this period, the Tamil country was under the rule of the Kalabhras, said to be tribal invaders from Karnataka following the Jaina faith. They displaced the traditional Tamil monarchies and held sway over the Tamil country for nearly three centuries until they were expelled in the last quarter of the 6th century A.D. by Kaṭuṅkōṉ, the Pāṇṭiya, from the south and Simhavishnu Pallava from the north. It is, however, significant that there is no inscriptional evidence for increased support to Tamil Jainism during the Kalabhra rule; on the contrary, the number of Jaina inscriptions decreased further during this period reflecting the unsettled conditions following the invasion. The earliest epigraphic evidence for the construction of temples and monasteries in brick and mortar is found in the Pulankurichi inscription of King Cēntaṉ Kūṟṟaṉ (ca. 500 A.D.). There is now a general consensus that he was a Kalabhra ruler as the name Kūrraṉ does not occur in the Pāṇṭiya dynasty, and as there is clear Kannada influence on the language of the inscription (e.g. avaru, ūru, aruḻḻittār, etc). The inscription relates to the administrative arrangements made for three places of worship, two of them Hindu (dēvakulam) and the other Jaina (tāpata-p-paḻḻi which was located in Madurai). The inscription provides evidence that the Kalabhras, acting in the tradition of the rulers of the land, did not discriminate between the Hindu and Jaina places of worship.

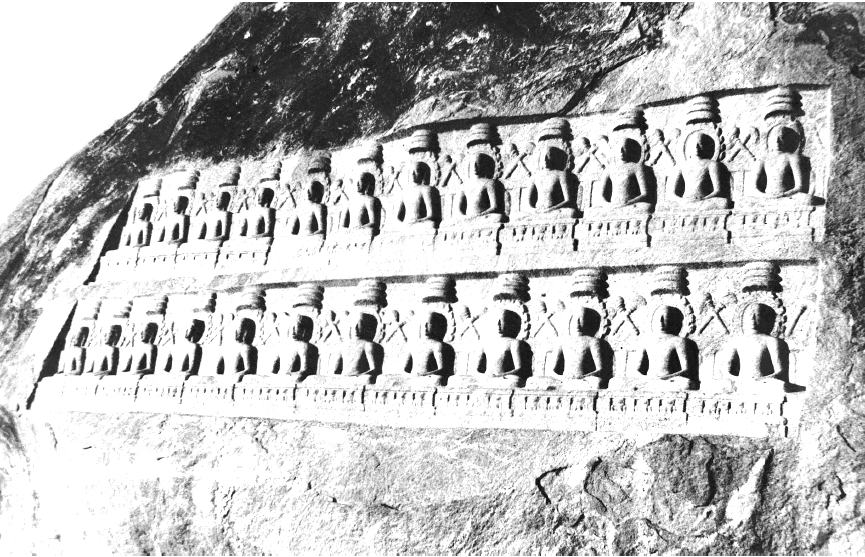

Re-occupation of the cave shelters by later Jainas

Jainism declined steeply in the Tamil country from about the end of the 6th century A.D. when there was a tremendous upsurge of the Saiva and Vaishnava sects revitalised by the Bhakti movement led by the Nāyaṉmār and Āḷvārs. The Tamil Jainas were persecuted during this period. However, the persecution, uncharacteristic of Indian polity, did not last too long and the rulers resumed grants to the Jaina monasteries (paḻḻi) from about the end of the 8th century A.D. as attested by epigraphical evidence from the Pallava and Pāṇṭiya regions (8th -10th centuries A.D.). It was during this period of revival that many of the earlier cave shelters with stone beds and Tamil-Brāhmī and/or Early Vaṭṭeḷuttu inscriptions were re-occupied by the Jainas who marked their renewed presence with relief sculptures (Plate 2.4) and inscriptions in the Vaṭṭeḷuttu script of the period.

Jaina contribution to Tamil Literature

No survey of Jainism in the Tamil country, however brief, can be complete without mentioning the enormous contribution made by the Jainas to the growth of Tamil literature from the earliest times up to about the 16th century A.D. While justice cannot be done to this vast subject within the scope of the present study, mention must be made at least of such outstanding works by Jaina authors like Tolkāppiyam and Naṉṉūl among the grammatical works, Cilappatikāram, Cīvakacintāmaṇi and Peruṅkatai among the epics, the immortal Kuraḻ and Nālaṭiyār among the ethical works and Tivākaram, Piṅkalantai and Cūṭāmaṇi among the lexicons. To this already formidable record may be added what is surely the most basic and fundamental contribution by the Jaina monks to Tamil viz., the development of a script for the language leading to literacy and the later efflorescence of Caṅkam literature in the early centuries A.D.

Influence of Old Kannada on Tamil-Brāhmī Inscriptions

The present study has brought to light the hitherto unsuspected influence of Old Kannada on the Tamil-Brāhmī inscriptions from a period (ca. 2nd century B.C.-4th century A.D.) anterior to the earliest known Kannada inscriptions and literature, especiallyfrom Sittannavasal (ca. 1st century B.C.), Tirupparankunram (ca. 1st century A.D.), Edakal (ca. 3rd century A.D.) and Nekanurpatti (ca. 4th century A.D.). Some of the more interesting lexical items and grammatical usages showing the influence of Old Kannada are listed below.

Lexical items

Erumināṭu is the same as LT erumaināṭu, the Mysore region (mahisha-maṇḍala) of Karnataka. The word erumi (Ta. erumai, Ka., Tu. erme, Go. ermi) 'buffalo' appears to preserve an ancient dialectal form.

kavuṭi is the personal name of the nun who is described in the inscription as born in a village in erumināṭu. cf. Ka. gavuḍi, gauḍi 'feminine of gauḍa, wife of a gāvuṃḍa, wife of a village officer'.

pocil 'entrance'. The expression occurs as part of the place name teṉku-ciṟu-pocil which appears to be the same as teṉ-ciṟu-vāyil, mentioned in the later Tamil inscriptions of the region as the name of the nāṭu (territorial division) immediately to the east of the hill at Sittannavasal. pocil is not attested in Tamil and appears to be related to Ka. hosilu (< *posil) 'entrance'. cf. also To. pōs 'entrance'.

tāyiyaru 'mother' (honorific). This is clearly a loanword from Kannada. The word occurs in New Kannada but is not attested in Old Kannada. However, as this inscription from Nekanurpatti is assigned to ca. 4th century A.D. on palaeographic evidence, we have to regard tāyiyaru as an Old Kannada word which existed in the spoken language but was not attested in contemporary records.

Personal names and honorifics

Personal names like āy(c)ca and polāl (a), and the suffixed honorifics aṇṇi, a(p)pa- and a(y)yaṉ / aiyaṉ appear to be more at home in Old Kannada onomastics.

Grammatical usages

-ā, occurring as the genitive suffix in some inscriptions is not attested in Tamil, but occurs in Old Kannada inscriptions where it is regarded as more ancient than –a.

-u, the euphonic suffix to stems ending in liquid consonants (e.g., ūru 'village') occurring mostly in the later inscriptions, is not attested in Old Tamil and appears to be due to the influence of Old Kannada, even though the suffix is attested in Kannada inscriptions only from the middle period (ca. 8th century A.D.).

Spread of Jainism from Karnataka

The presence of Old Kannada elements in the Tamil-Brāhmī inscriptions corroborates the traditional account of the spread of Jainism from Karnataka into the Tamil country.

Protect the Jaina Monuments

The Jaina monuments in the Tamil country face very real danger of serious damage by tourist vandalism and breaking up of the rocks for export of granite. I hope that my publication would help in creating greater awareness on the part of the Central and State Departments of Archaeology and the local citizens to take more vigorous steps to protect and preserve the priceless heritage of Jaina monuments of Tamilnadu.

Dr. Iravatham Mahadevan

Dr. Iravatham Mahadevan