10

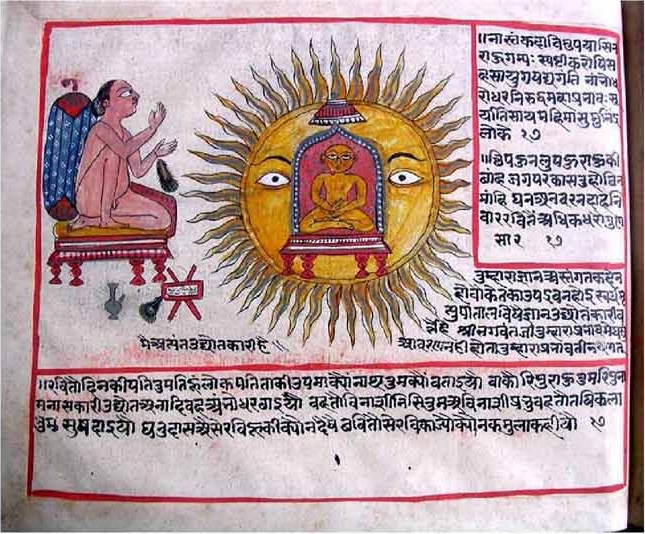

Illustrating the Bhaktāmara Stotra

The University of Michigan Museum of Art has in its collection 18 folios of an unidentified Jain manuscript assigned to the 18th century and to Sirohi. [1] Two more folios of the same manuscript are in the Los Angeles County Museum and are also unidentified. Photographs of the folios are available on the museum websites, and one of the folios in Los Angeles is published by Pratapadatiya Pal in the Peaceful Liberators, where it is identified simply as “Lustration of a Jina” and assigned to the early 19th century Gujarat. [2] Sirohi seems to be more likely as the place of origin of the manuscript. The Michigan manuscript closely resembles a Vijñaptipatra from Sirohi now in the Spencer Collection of the New York Public Library and dated 1761.[3] It also shares many features with a Vijñaptipatra in the Delhi Museum, also from Sirohi and dated 1737. [4]

The illustrations have been separated from the text, which has made their identification difficult. In fact, comparison with an intact manuscript belonging to the Oriental Research Institute in Ara, Bihar, and recently digitized and put on the web by the International Digamber Jain Organization makes it clear that the Michigan folios belong to an illustrated Bhaktāmara Stotra. [5] The Bhaktāmara Stotra enjoyed and continues to enjoy unusual popularity among all Jains. Scholars have argued that the hymn was composed by a Śvetāmbara monk sometime around the 6th century. Digambaras also count its author as one of their own and depict him in the paintings as a Digambara monk.[6] The Digambara version of the hymn contains 48 verses as against the 44 of the Śvetāmbara version. Illustrated manuscripts of the hymn are rare, and I have seen only Digambara illustrated manuscripts. None predates the 17th century. Considering the large number of manuscripts of the hymn itself, there are surprisingly few illustrated examples that are known to date.[7] It is also somewhat surprising, given the long history of Jain manuscript paintings, that the known manuscripts are all so late. Much remains to be studied about the tradition of illustrating the Bhaktāmara, and this is a small contribution to what must be a much larger endeavor.

The Michigan manuscript is an outstanding example of late Jain manuscript painting. There are two types of illustrated Bhaktāmara manuscripts. One deals with magic diagrams and the other with illustrations to the verse themselves. I will only be concerned here with the illustrations to the verses. [8] In addition to their esoteric associations with magic formulas and diagrams, every verse of the hymn also came to be associated with a story that vividly describes the miraculous results of reciting a particular verse. These stories, many of which are known from other didactic story collections, were told in commentaries to the verses. [9] Interestingly, the illustrations to the hymn in the manuscripts with which I am familiar do not depict events in the miracle stories, but are intended to illustrate the verses themselves. This is somewhat different from what we see in illustrated manuscripts of other texts, and I should add in recent publications of the hymn that include illustrations. A new Gujarati book, for example, includes a wide range of miracle stories, which it illustrates. Traditionally, among the Śvetāmbaras, illustrated manuscripts, for example of the Kalpasūtras or Uttarādhyayanasūtras, also included illustrations of the material in the commentaries in addition to the root text itself, perhaps because of the ease with which such narratives lend themselves to illustrations, in contrast to the more abstract contents of the texts. One of the unique features of the illustrated Bhaktāmara stotra manuscripts that I have examined is the skill which the illustrators have found a way to depict the most abstract concepts, often by relying upon small visual clues within the verses themselves, and at other times making use of commonly accepted metaphors.

In their efforts to depict abstractions these painters seem to me to be closer to the sculptors of images of the Jinas that to painters of narrative scenes. The sculptors endeavored to convey the abstract notion of the extraordinary knowledge of the Jina through the perfection of his physical body. According to one medieval monk, every Jina image in its perfection was to remind us of the Jina in his preaching assembly. The preaching assembly was itself a reminder of the Omniscience of the Jina. In fact, depicting the preaching assembly or samavasaraṇa was the standard way in which manuscripts of the Kalpasūtra portrayed the Omniscience of the Jina.[10] We shall see that the artist of the Bhaktāmara in a similar fashion relied on accepted images and generally shared understandings to illustrate such an abstract concept like knowledge.

I begin my discussion of the Michigan manuscript of the Bhaktāmara Stotra with verse 20 of the hymn, a praise of the Jina’s unique knowledge:

“The knowledge that shines within you, reflecting every object in the universe, has no place in the other gods, like Visnu and Siva. Great is the light that glitters from gemstones; glass is worthless, no matter how much it sparkles. “

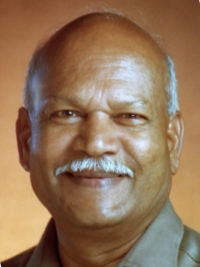

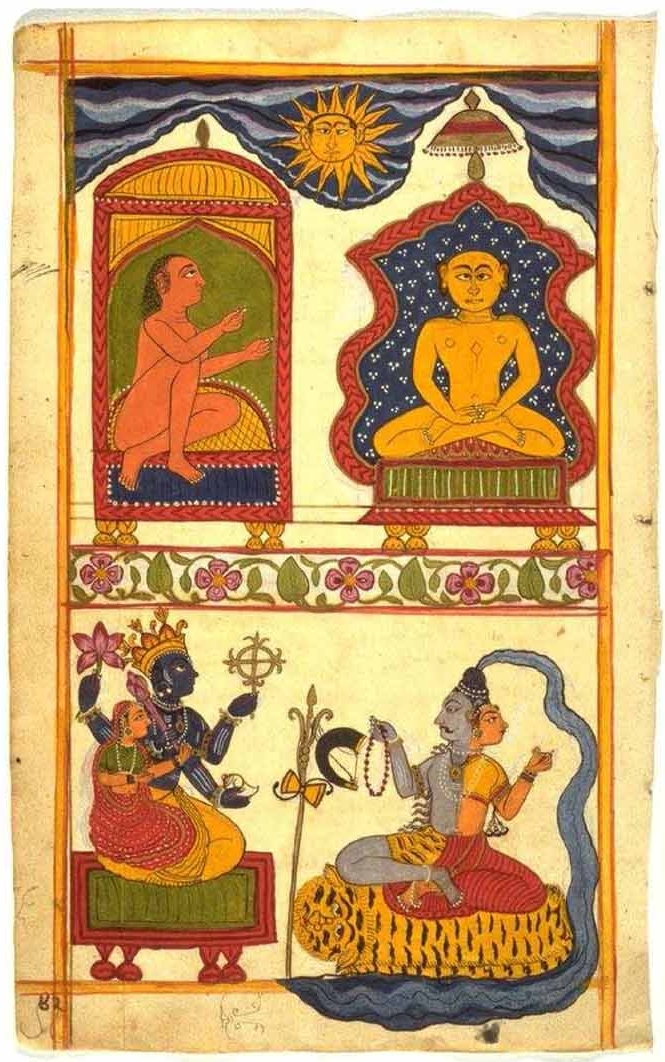

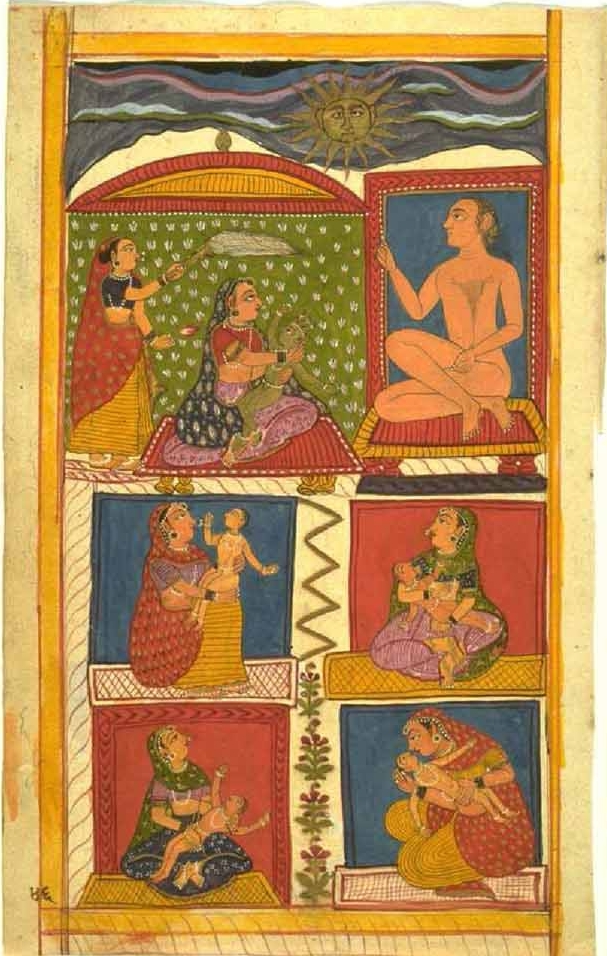

In plate 10.1, which illustrates this verse, we see the Hindu gods, Viṣṇu and his wife Laksmī and Śiva and his wife Pārvatī, in the bottom register. Śiva and Pārvatī appear in the conjoined form as Ardhanarīśvara. Above Viṣṇu and Lakṣmī the seated monk Mānatuṅga, author of the hymn, gestures both to the seated Jina and upwards to the sun, with its radiant light. In the Ara manuscript (Plate 10.2), the Hindu gods are off to one side, while the sun is placed very obviously directly above the head of the standing Jina. The monk gestures toward the sun and the Jina. It is the sun here that represents the awesome knowledge that the Jina possesses.

The knowledge of the Jina and the Jina himself were often compared to the radiant sun, removing the darkness of ignorance. Mānatuṅga himself uses the comparison in several verses of the hymn. In verse 7 the poet sings,

“All the sins that living beings have accumulated over countless rebirths vanish without a trace when they praise you, just as the bee-black darkness of night, spread out over the world, vanishes in the rays of the sun.”

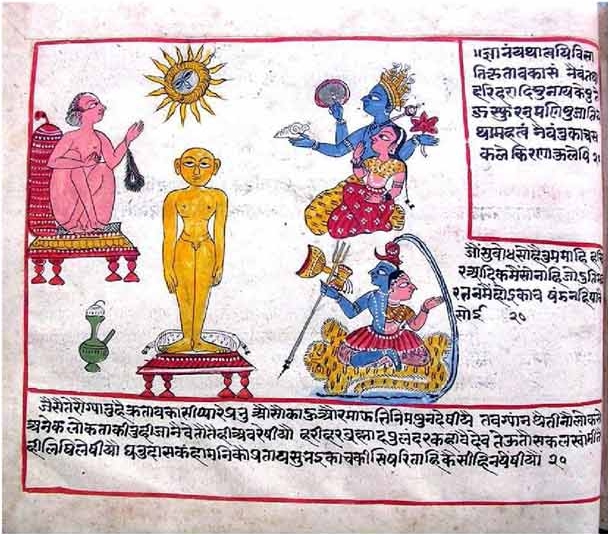

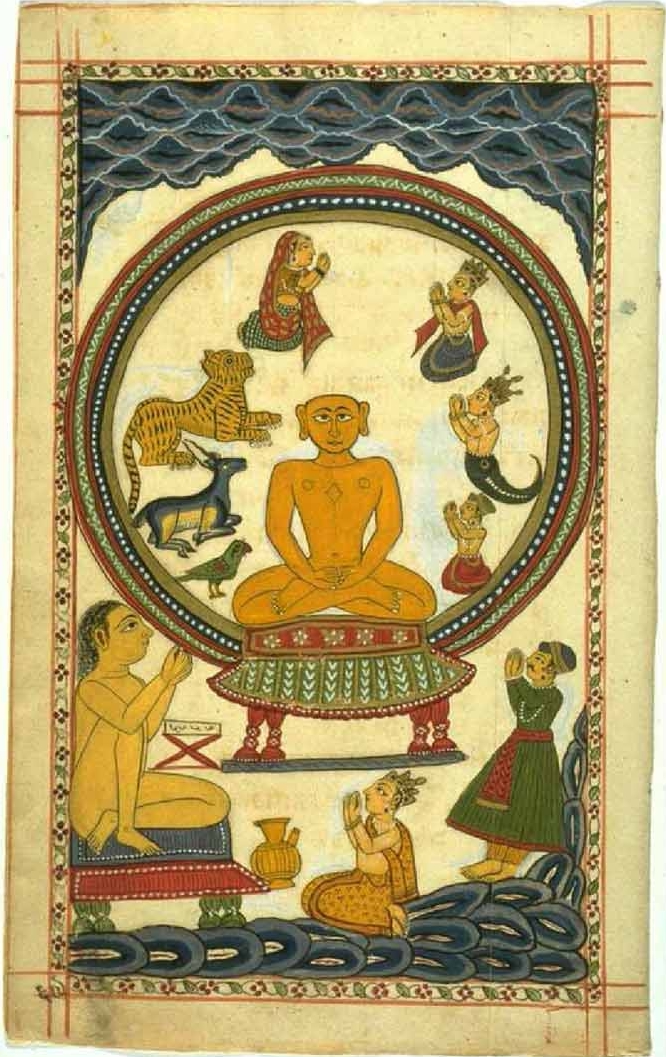

And in verse 17 the poet praises the Jina as even greater than the sun, for the knowledge of the Jina makes known or illumines all the worlds at once and is never obstructed, while the sun sets and illuminates only a fraction of the worlds at any given time. The illustrator of the Ara manuscript for this verse depicted the seated Jina inside a giant sun to show the Jina’s extraordinary knowledge (Plate 10.3). This illustration is lacking in the Michigan manuscript, but it is clear that the sun as a metaphor for knowledge would have been easily recognized.

Verse 20 and its illustrations celebrate not only the unique power of the Jina’s knowledge, but also the superiority of the Jina over the Hindu gods that results from the fact that only the Jina has such knowledge. The Michigan manuscript places the Hindu gods in the lower register, while we have seen that the Ara manuscript places them off to the side and in a posture that could even be construed as a gesture of worship to the Jina. In medieval poetry, Jain monks stressed that the superiority of the Jina over the Hindu gods could be seen from the Jina image itself, for the Jina is always depicted without weapons and without a wife, indicating his espousal of non-violence and his complete renunciation of sensory pleasures.[11] In both figures 1 and 2 the Hindu gods are shown with their wives, though the verse does not mention them, and their weapons are clearly shown, perhaps to emphasize their difference from the Jina, who is alone, without adornment and without any weapons. The desire to emphasize these unique virtues of the Jina may also explain why the artists have chosen the conjoint form of Śiva and Pārvatī, for Hindu legends tell us that their love and longing for each other were so great that they could not bear the slightest bodily separation and fused into one form. The Ardhanarīśvara form, then, is the ultimate depiction of lust at its highest most uncontrollable level. There is something else of interest here. If you look closely at the Michigan folio, at the bottom just under the throne of Viṣṇu-Lakṣmī and beyond the yellow border you will see that the artist has practiced drawing faces on the margins of the illustration. He has practiced the double head of the Śiva/Pārvatī, suggesting perhaps that he was not accustomed to drawing these Hindu deities.

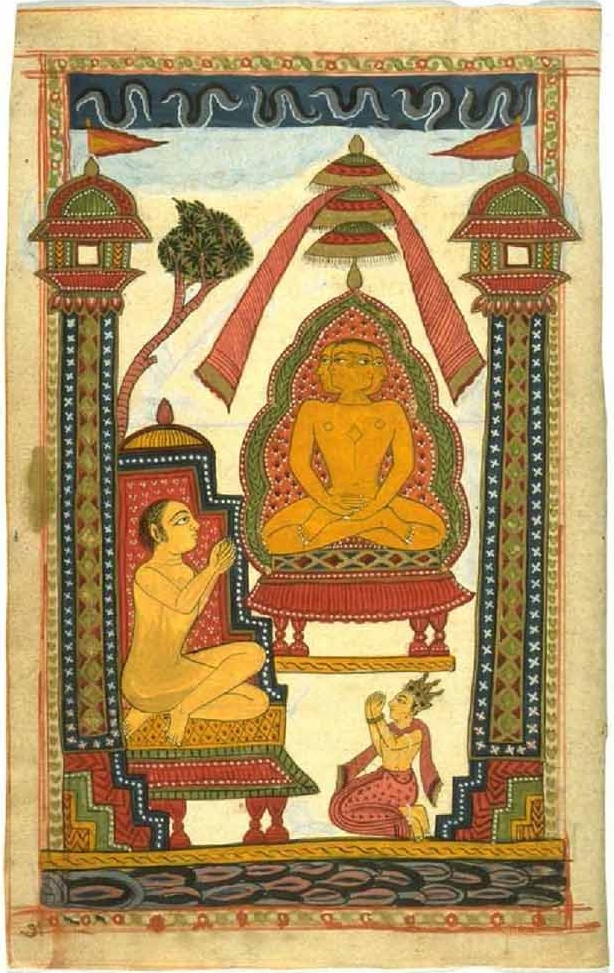

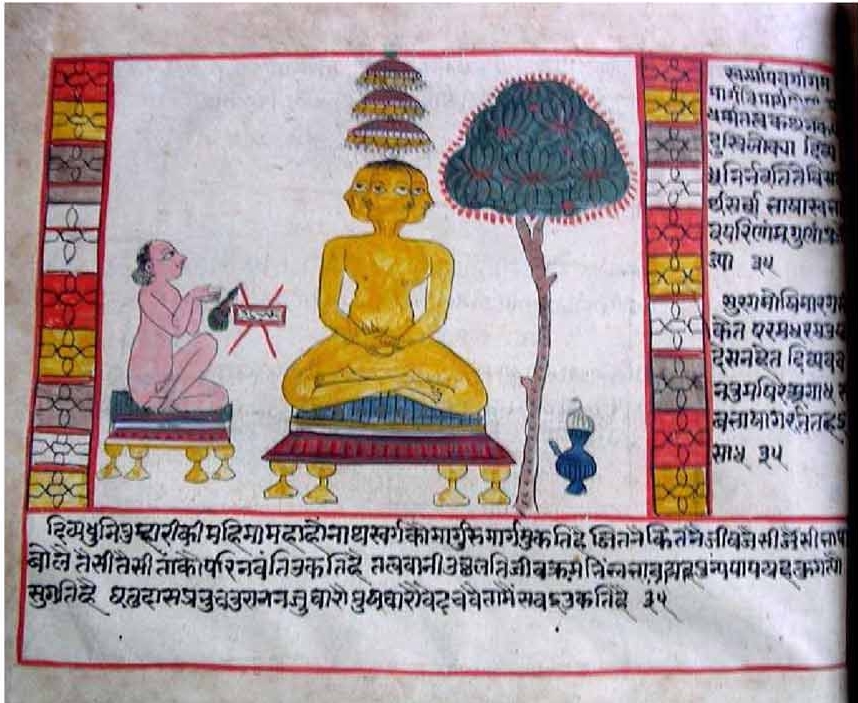

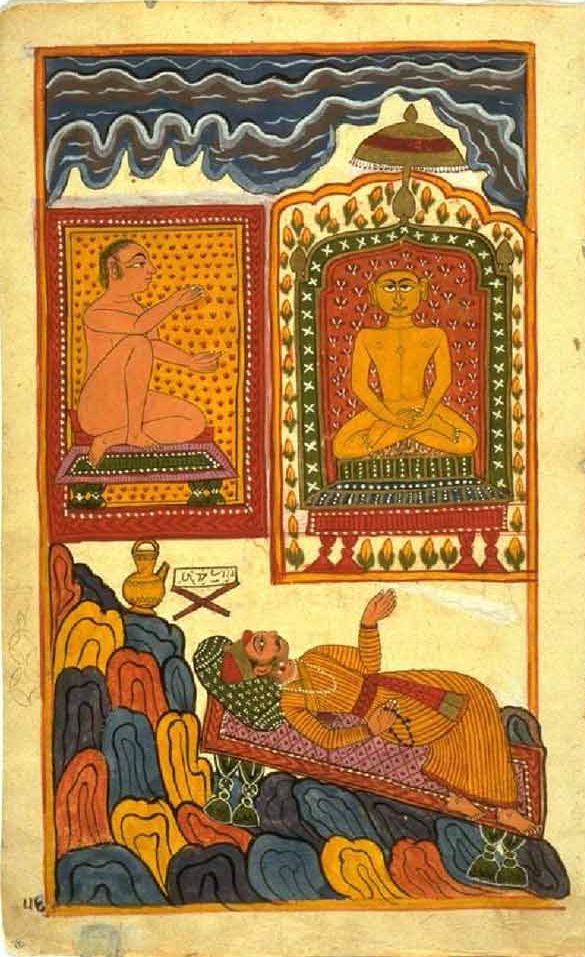

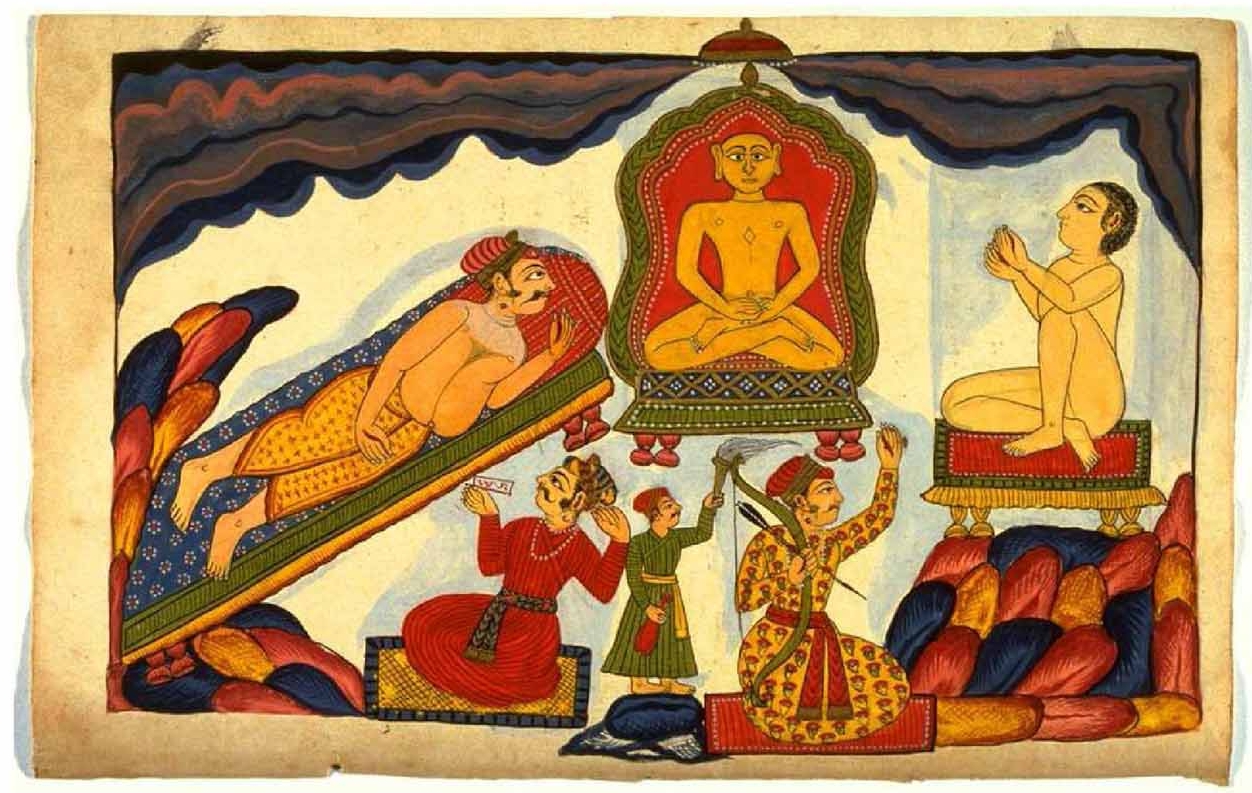

Plates 4 and 5 illustrate verse 35 in the Digambara version of the hymn, a verse that is not found in the Śvetāmbara version. The Michigan manuscript (Plate 10.4) shows the Jina seated on a throne with a triple parasol above him. The Jina appears to be four-headed. Mānatuṅga worships the Jina, while a small, crowned and adoring figure, no doubt a god, is shown at the bottom of the illustration. The composition is framed by architectural elements at either side, A dark cloud band at the top is echoed by the rocky landscape at the base. The Ara manuscript (Plate 10.5) shows the same four- headed Jina with Mānatuṅga at the left. To the right is a tree and water pot. The verse praises the miraculous speech of the Jina at his first preaching, immediately following his Enlightenment. The speech of the Jina is not like ordinary speech. Among its unique qualities are these: every living being hears it in his own language, and it resounds throughout the universe. For medieval Jain monks, it was not only the physical beauty of the Jina’s form that gave proof of his Omniscience. His marvelous speech was also a direct indication of his incomparable knowledge. [12] Here is how Mānatuṅga praised the speech of the Jina in verse 35:

“Your words are savoured by those who desire to find a path to heaven or to Final Release; only your words are capable of revealing the true dharma; miraculous, they transform themselves into many languages so that each living being can understand them.”

Seeking for a way to represent something as abstract as “speech”, the illustrator again resorts to an allusion to something familiar, in this case the setting in which the Jina uttered his miraculous speech. At the first preaching that immediately followed the Jina’s achievement of Omniscience, one of the miracles is that the Jina can be seen from all four directions. The artist has attempted to convey this by means of the multiple heads. He relies here on a series of associations to illustrate the abstract notion of the Jina’s miraculous speech. The Jina who can be seen from all four directions is the Jina in the first preaching assembly. The marvelous speech of the Jina, the subject of the verse, is in turn manifested at that preaching assembly. If the sun was a metaphor for the Omniscience of the Jina in the illustration to verse 20, the Jina looking in all four directions is a metonym for the preaching assembly, the setting for the divine sermon, which in turn calls to mind the first sermon and the miraculous nature of the Jina’s speech.

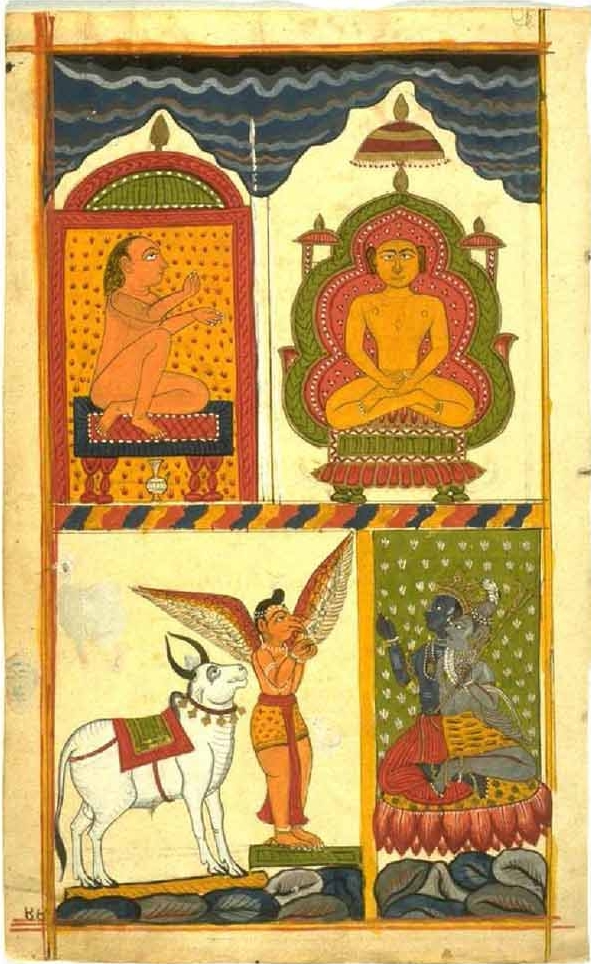

I would suggest that the illustrators relied again on familiar images in this next illustration (Plates 10.6 and 10.7). We see in lower register Garuḍa, the bird mount of Viṣṇu and next to him, Nandin, the bull of Śiva (Plate 10.6). Garuḍa has his hands folded in reverence. To the right are Śiva and Viṣṇu, in the combined form of Hari-hara.. In the top register the Jina is seated on a throne, with Mānatuṅga at his side. This illustrates verse 21, which is another verse about the superiority of the Jina over the Hindu gods. In a playful tone the poet says,

“I would rather see Śiva and Viṣṇu, for whenever I see them my heart filled with devotion to you. But when I see you, o Lord, there is nothing else that can give me pleasure, now and forever more.”

Garuḍa and Nandin are examples of absolute devotion in Hindu mythology, and one suspects that their gesture of reverence is meant for the Jina. Both gaze upward, and Nandin is standing on a platform that even tilts upward towards the Jina. That this is the case is clear from the comparison with the Ara manuscript (Plate 10.7), where the gods and their mounts are all worshipping the Jina. The Ara illustrator has stressed Mānatuṅga’s devotion to the Jina; here Mānatuṅga is depicted standing and raising his arm toward the Jina in a dramatic gesture.

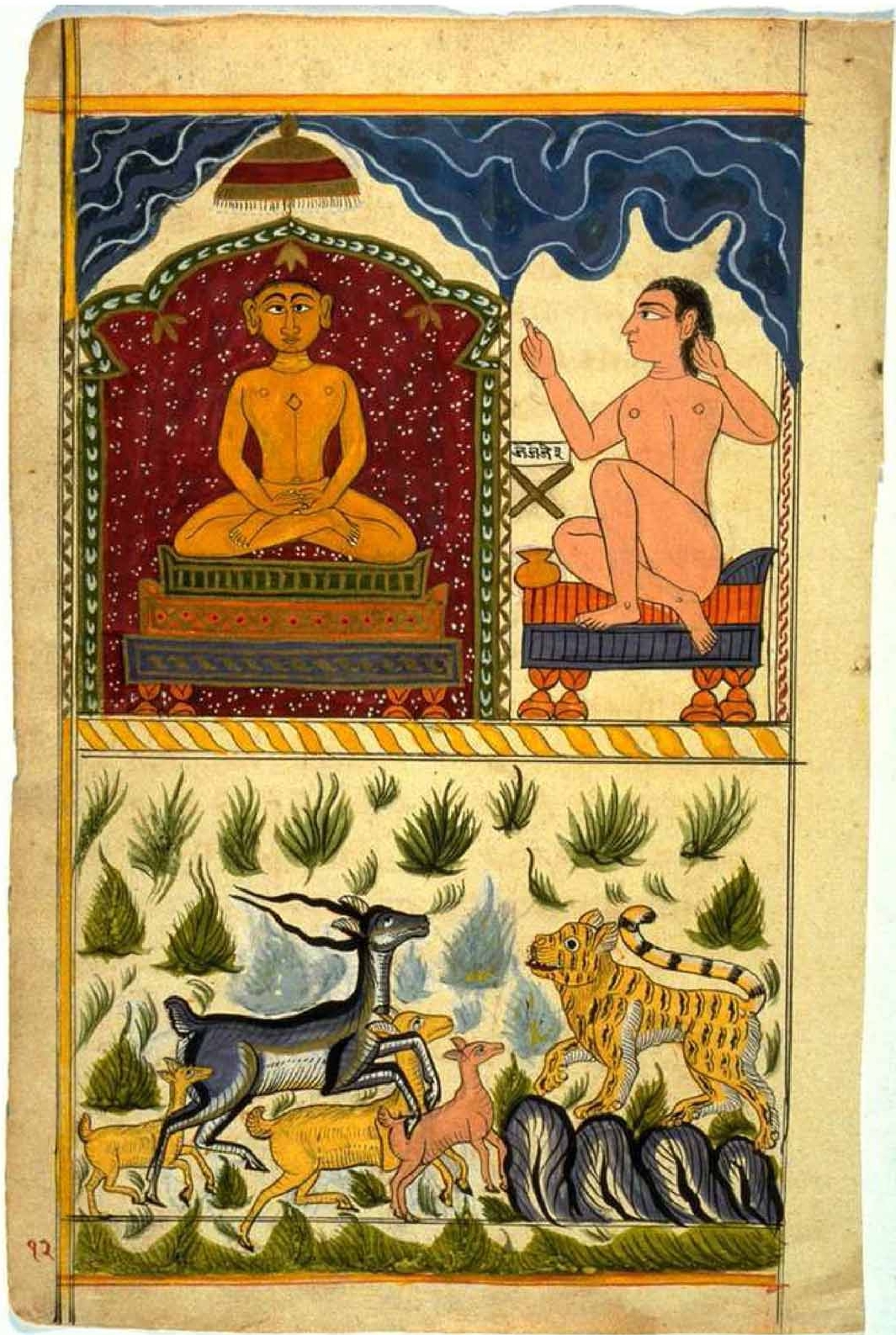

All of these examples, I would argue, rely on the viewer’s familiarity with certain ideas or visual clues that are not directly expressed in the illustrated verses themselves, but belonged to generally accepted cultural knowledge. In other cases the verses themselves directly provide a concrete visual clue for the illustrator even when the verse revolves around something abstract. It is standard in devotional poetry for the poet to proclaim his own unworthiness and to say that it is only his deep love for the deity that impels him to commit the rash act of trying to put into words the greatness of God, something that is truly beyond the range of human comprehension or language. In verse 5 Mānatuṅga says,

“O Lord of sages, incompetent though I am, I have begun this hymn of praise to you out of devotion. Doesn’t the deer out of love rush towards the lion to protect her fawn, not for a moment thinking of her own weakness?”

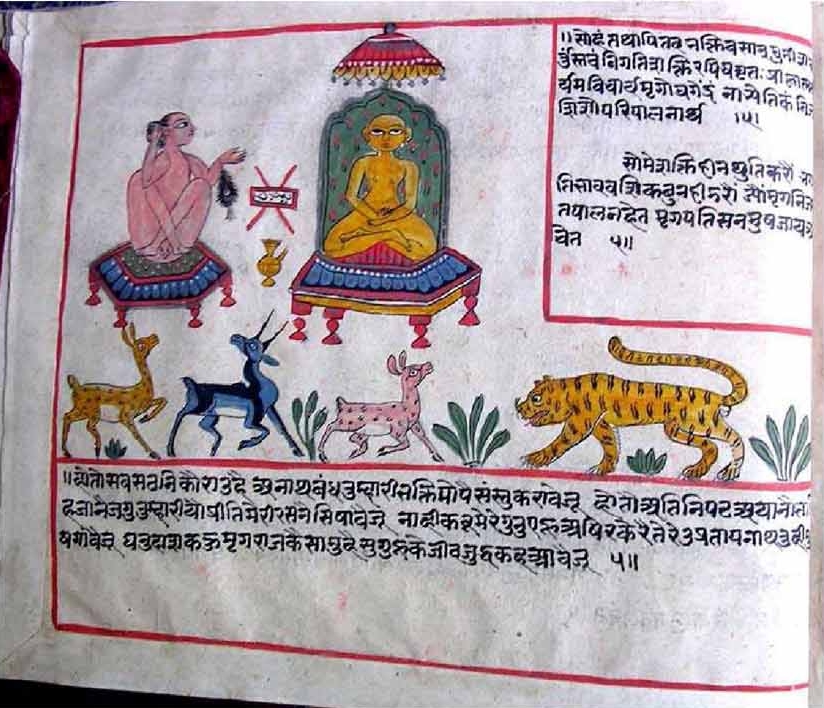

Plate 10.8, which illustrates this verse, is one of the finest illustrations in the Michigan manuscript. Typical of all the illustrations in the manuscript the actors are carefully separated from each other by various devices. In the top register we see the Jina seated on a three-tiered throne, framed by an architectural niche. Mānatuṅga is beside him, with a water pot on his seat and a book on a stand.. The book has letters in Devanagari on it; other books on other folios will have unreadable writing that looks more like Arabic script than like Devanagari. The space that Mānatuṅga occupies is clearly marked off from the larger niche in which the Jina sits by the presence of what might be columns, two vertical areas with geometric patterns. The lower register is set off by a thicker border with diagonal yellow lines. There we see a deer rushing at a lion, her three fawns protected by her body. Waving trees heighten the drama of the scene. The skill of the illustrator is immediately apparent from a comparison with the less elegant, more folksy Ara manuscript in Plate 10.9.

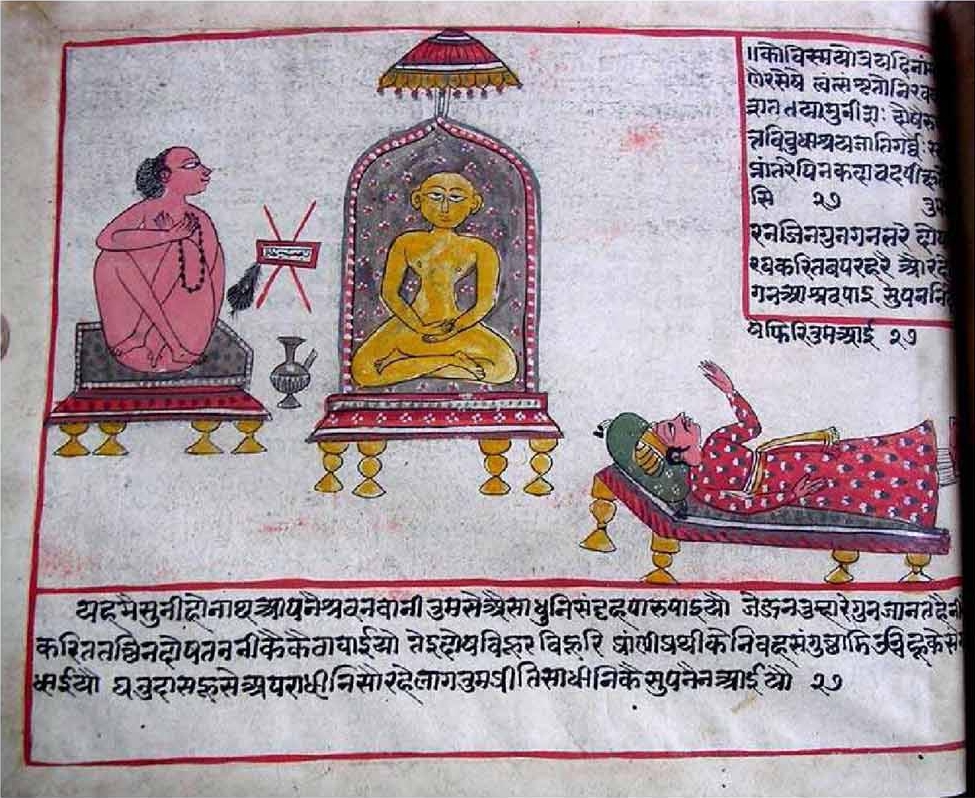

In a similar manner, Plates 10 and 11, illustrations to verse 27, latch on to a potential visual clue within the verse itself to illustrate an abstract thought. The verse reads,

“ O Lord of Sages! What wonder is it that every conceivable virtue is found in you, leaving no space for anything else. For even in my dreams I never see a hint of any of those flaws that boast of being everywhere in the world.”

It is the reclining, dreaming figure that alerts us to the rest of the content of the verse, a celebration of the many virtues of the Jina.

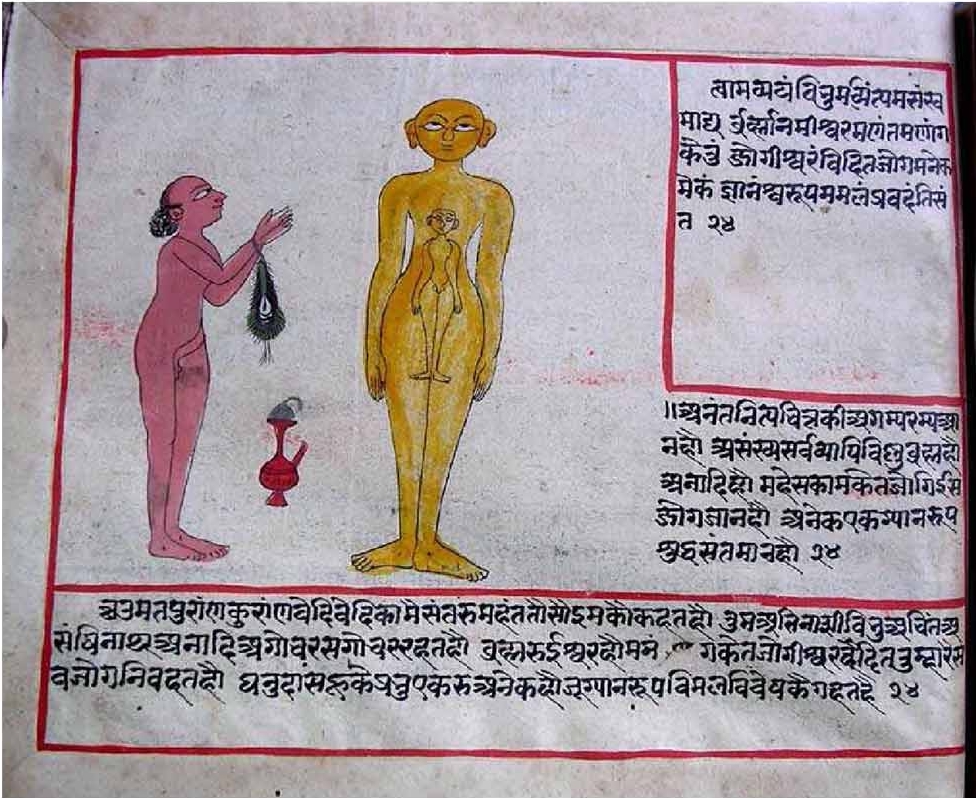

Not all the artistic choices seem equally felicitous. The Michigan manuscript lacks the illustration for verse 24, a verse that praises the Jina in terms often used in Indian philosophical texts. Mānatuṅga tells us that the wise know the Jina as the impersishable one, the lord of Yogins, the one who is beyond thought, immeasurable, the primordial one, all pervasive, both one and many. In the Ara manuscript (Plate 10.12), we see the standing Mānatuṅga offering reverence to a standing Jina, on whose surface an identical smaller Jina figure has been delineated. Perhaps this is meant to show that the Jina is both one and not one. The commentator explains this apparent contradiction in several ways. One explanation he offers is that as a category or a group the Jina is one, but there are also 24 individual Jinas in each world cycle.

Many of the verses of the hymn offered few such problems for the illustrator. They describe either concrete visual features of the Jina or Jina image, or the concrete benefits that accrue from reciting the verses of the hymn. Plates 13 and 14 illustrate verse 22, which praises the mother of the Jina. Hundreds of mothers have given birth to hundreds of sons; only one mother gave birth to the Jina. The next two figures (Plates 10.15 and 10.16), illustrate verse 34, praising the glorious halo that surrounds the the Jina on his Enlightenment. The presence of the halo is one of the eight prātihārya or so-called miraculous manifestations that accompany the Jina after his Enlightenment. Here the verse describes how the Jina’s halo of light puts to shame all the heavenly bodies. Greater than a multitude of suns, it is also gentler than the moon at night. The poet means to say that the light of the Jina’s halo is comforting not burning, something that is said in Sanskrit poetry of the light of the moon. At the same time, the light of the Jina is as brilliant as the light of countless suns. And by this seeming paradox the poet tells us that the light of the Jina’s halo is not of this world. The Michigan illustrator (Plate 10.15) has chosen to depict the greatness of the halo by making it large, the round circle filling most of the picture space. The Michigan halo with its concentric circles also suggests the miraculous preaching assembly, which in turn alerts us to the marvelous appearance of the halo. Both illustrators show a host of creatures, animal, human and divine worshiping the halo.

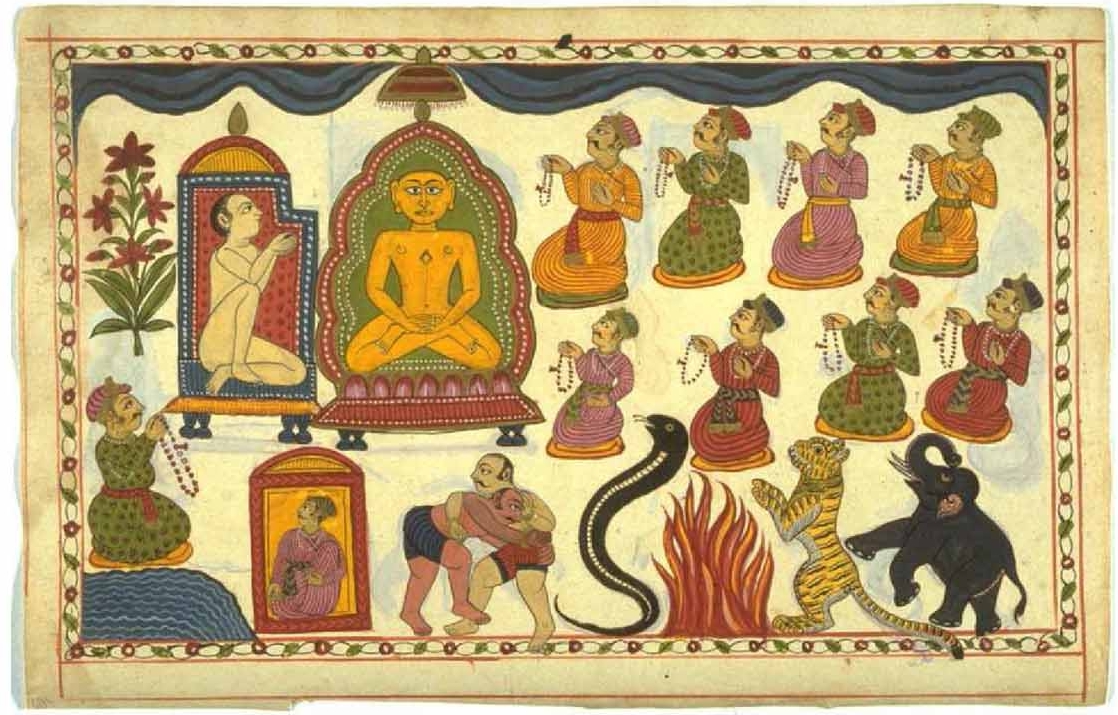

Recitation of specific verses of the hymn is said to bring specific benefits. One of the diseases that it cures is jalodararoga, or dropsy, in which the belly swells. Plates 17 and 18 illustrate verse 45. We see the patient lying on a couch, belly visibly swollen. The verse tells us,

“Those who have been utterly wrecked by their burdensome swollen abdomens, who are plagued by the terrible disease of dropsy and have given up all hope, become as handsome as the god of Love himself, their bodies anointed with a life-saving nectar, the dust from your lotus feet.”

Reciting this verse in prayer to the Jina brings relief from this unendurable disease.

The hymn can also protect against snakes and attack by wild beasts or enemy armies. It can even free a person who is tied up in chains and cast into a dungeon. Plates 19 and 20 illustrate verse 47, which sums up the virtues of reading or reciting the hymn: a person who studies this hymn has nothing to fear from wild elephants, lions, fires, battles, the ocean, dropsy or imprisonment.

The Bhaktāmara Stotra continues to be illustrated today. It is depicted in stone on the remarkable temple at Sanganer, for example (Plates 10.21 and 10.22).[13] The stability of the iconographic tradition was already apparent from a comparison of the two manuscripts discussed in this paper, and now the reliefs on the temple at Sanganer tell us that much of the iconographic program has been maintained over the centuries and despite the change in the medium. Once some unknown artist achieved this remarkably successful language to convey in painting what Mānatuṅga the hymnist had said in words, that visual language would seem to have been remarkably consistent. Indeed, in the case of the Michigan and Ara manuscripts, so similar are the illustrations for any given verse that I was able to identify the subject of the Michigan manuscript immediately on finding the Ara manuscript. Our awareness that these are illustrations to a poem might help us to appreciate the stability of the artistic formula. These paintings use visual images as their words, just as they rely upon widely shared metaphors and other figures of speech. Recognition and familiarity are important; the viewer has to know the language of these illustrations, just as someone who reads the hymn has to know the language in which it is written and its literary conventions. And here I think that literature and literary theory can help us with another question that these manuscripts raise: originality or lack of it. Sanskrit writers take as dim a view as we do of plagiarism, and they had a remarkably subtle understanding of originality. It is not afraid of the works of other poets, but demands of the true poet some creative touch in the use of a traditional image.[14] I do not think that anyone would doubt the creativity of the Michigan artist. Using a language that others also spoke and relying on a shared vocabulary of images, the Michigan artist has nonetheless created a great poem.

Plates

Plate 10.1

Plate 10.2

Plate 10.3

Plate 10.4

Plate 10.5

Plate 10.6

Plate 10.7

Plate 10.8

Plate 10.9

Plate 10.10

Plate 10.11

Plate 10.12

Plate 10.13

Plate 10.14

Plate 10.15

Plate 10.16

Plate 10.17

Plate 10.18

Plate 10.19

Plate 10.20

Plate 10.21

Plate 10.22

Accession numbers 1975.2. 153-180. The manuscript is 28.9 cm x 18 cm (11 3/8 in 7 1/16 in.). Photographs courtesy of the museum.

The Peaceful Liberators: Jain Art from India, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1994, figure 37, page 50. This is one of the opening folios of the illustrated Bhaktāmara, which typically begins with scenes from the life of the first Jina, Ṛṣabhanātha. Accession numbers AC 1975.2.165;178.

Madhusudan Dhaky and Jitendra Shah, Mānatuṅga aur unke Stotra, Ahmedabad: Sharadaben Chimanbhat Educational Research Center, 1997. See also John Cort, “Devotional Culture in Jainism”, Mānatuṅga and his Bhaktāmara Stotra”, in James, Blumenthal, ed., Incompatible Visions: South Asian Religion in History and Culture Essays in Honor of David Knipe, Madison: University of Wisconsin, Center for South Asia, 2006, pp. 93-115.

A manuscript dated 1773 A.D. has recently been published: Mānatuṅga, Bhaktamara Stotra (Sacitra). Mahavirji: Jain Vidya Sansthan, 2005. The book has been reviewed by John Cort, ACSAA, 66, Fall/Winter 2006, pp. 15-16. I thank John for a copy of the review and his articles on the Bhaktāmara. John notes in the review, p. 16, that Saryu Doshi in her book, Masterpieces of Jain Painting, Mumbai: Marg Publications, 1985, p. 77, in passing mentions illustrations to the hymn and published a black and white photo of a manuscript painted in Bikaner in 1694.

The website of the International Digamber Jain Organization also includes several remarkable Bhaktāmara manuscripts with delicately colored yantras.

The hymn has been edited many times. The edition of Professor Hiralal Rasikdas Kapadia in the Śreṣṭhi Devacandralālbhāī Jain Pustakoddhāra Series 79, Bombay: Nirnayasagara Press,1932, contains a commentary with miracle stories. For information on Jain tantra, see the references I gathered for the catalogue, The Victorious Ones, New York: Rubin Museum of Art, 2009, p. 297.

Samayasundara, “When one sees the Jina image one recalls the real Jina in the midst of his wondrous preaching assembly. And when one recalls the Jina and thinks upon his virtues, there is a great gain. At once bad future rebirths are prevented and a good rebirth is insured.”, Sāmācārī Śataka, verse 40. The text is published in the Srī Jinadattasūri Prācīna Pustakoddhāra Fund, 41, Surat 1939. I have discussed the role of memory and art, particularly Jain art, in a forthcoming paper, “Bewitching Beauty: Some Jain Reflections in Art: in a festschrift for Koichi Shinohara edited by James Benn and James Robson, Mosaic Press.

Thus Hemacandra, “The Jina is called Śamkara, ‘The One who Brings Peace’, because it is he who is Śiva, ‘the Auspicious One’. Whether standing or seated in meditation, he is without weapons and unaccompanied by a wife”. This is from the Mahādevastotra (verse 15), Kalikāla-sarvajña-śrīhemacandrācāryaracitā Stotratrayī, Peṭalādavālā: Sa. Bhāīlāl Ambālāl, V.S. 2016 (1936), p. 20. For further references see my paper cited above.

Siddhasena in his first Dvātriṃśikā, verse 14, states that the body of the Jina, which is always unchanging, devoid of ordinary red blood, and his marvelous speech suffice to convince even the most ordinary person of the Jina’s true Omniscience. Dvātriṃśad-dvātriṃśikāḥ tatra prathamā dvātriṃśikā with commentary of Vijayalāvaṇyasūri, Śrīvijayanemisūrigranthamālāratna, 38, Saurashtra: Śrīvijaya-lāvaṇyasūrīṡvara Jñānamandira, 1951, p. 22. My paper cited above includes other verses from this text

Prof. Dr. Phyllis Granoff

Prof. Dr. Phyllis Granoff