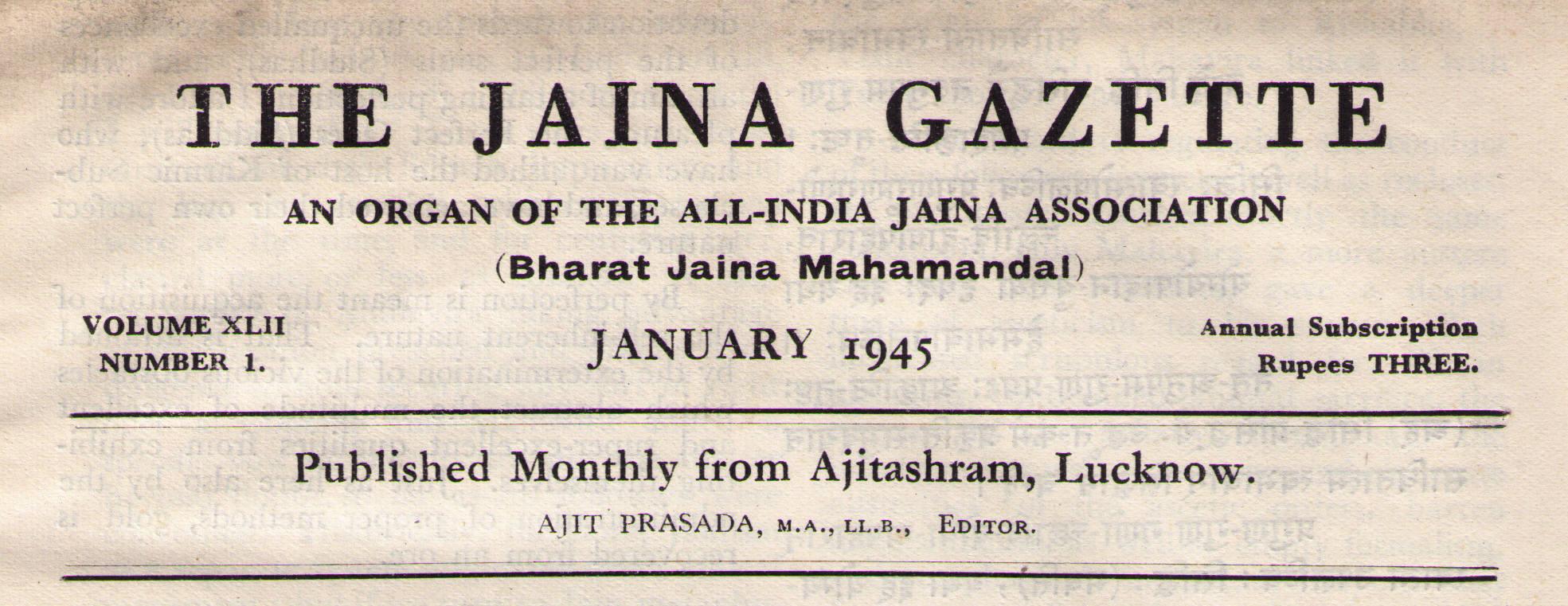

The essay was published in The Jaina Gazette, Vol. XLII, Number 1, February 1945, pp. 2-5.

Jaina Ethics (I)

Jainism is regarded by some scholars than logical or metaphysical. The earliest as essentially an ethical system, but the Jain teacher, recognised as a historical reasons for this view are historical rather character, was Parsvanath who flourished about 800 B.C. and he is best known as the author of four vows which he administered to his disciples:

- I will not kill,

- I will not steal

- I will not lie and

- I will not possess

These vows were to be observed in their fullness by ascetics; and the last one covered celibacy as women were at the time, and for centuries later, classed more or less as chattels. A contemporary of Mahavira taking advantage of this position preached and practised indulgence without securing any sort of right over a woman, and Mahavira added a specific vow of chastity to put the matter beyond doubt, so far as his followers were concerned. Historically, therefore, Jainism as a separate system originated in an ethical movement; but if we turn to Jain metaphysics as it has come down to us, to find out the sanction for morality, the goal of human life, the theory of salvation, etc., the position is very much the same in Jainism as in most other Hindu systems with the exception of Buddhism as taught by Buddha himself.

Whatever views Buddha might have held about god and soul, he studiously avoided propounding any theories on these topics, and addressed himself direct to the practical work of finding a cure for human suffering. Putting desire as the root cause of suffering, the remedy prescribed by him was a life of purity and love and selfless benevolence, which would in due course, may be after ages, bring about enlightenment and the experience of supreme bliss called by him nirvana. On the other hand Mahavira, who was senior to Buddha by some years, put his theory of the self, its bondage and emancipation in the forefront of his teaching, from which he deduced the rest of his system. It was probably this lack of a distinct philosophy that drove Buddhism out of India when its practical programme of social reform had been accepted by Hinduism. We have seen a similar phenomenon in our own day in the course of the Brahmo Samaj and the Arya Samaj. Jainism survived because it had a philosophy of its own, though by tracing the origin of his system to Rishabha, vedic character, Mahavira linked it with vedic thought and culture.

With regard to regulating the conduct of their followers, laymen as well as recluses, the two masters reached exactly the same conclusion, only Mahavira, a more austere character than Buddha, gave a deeper tinge of asceticism to his system. Both inculcated scrupulous regard for life in all forms, condemned animal sacrifice, the tyranny of the priestly classes, and the indulgence as well as excessive and elaborate austerities of the ascetic orders, barren intellectualism as well as empty formalism, and emphasized individual responsibility for purity of conduct. Both regarded freedom from desire as the indispensable condition of salvation. Both adopted similar terminology and technique for indicating the course of spiritual progress. Both were inspired by some sort of spiritual experience, but, Buddha never tried to define it, whereas Mahavira wove round it a complete philosophy of religion; though strictly speaking he also considered Reality inexpressible in words.

Jainism, in common with most of the Hindu systems, recognises four objectives of human endeavour:

performance of socio-religious duties making an honest living legitimate enjoyment final emancipation

With regard to the first three, the Jaina scheme is very much the same as that of the other Hindu systems. Good deeds are rewarded in this life or hereafter in heaven or on the earth itself in a better environment. Bad deeds are similarly punished. The law of karma reigns supreme, the god of the theistic systems being himself subject to it. In all these cases the sanction behind morality is the word of an omniscient Being; only the omniscient being of Jainism is the individual self, which when freed from the handicap of karma reveals all the attributes of godhead, omniscience, omnipotence and bliss. Emancipation being the highest objective, the others should be regulated in such a manner as to lead up to it.

The conception of the self, the knowing self, different from everything that can be called "mine" - possessions, relatives, body, senses, appetites, passions, emotions, pain, pleasure - thus becomes the basic feature of the Jain doctrine. It is identified with the divine pure consciousness is the one attribute of the soul, in it; purity, other faculties being due to association with karma (action). When the soul is freed from karma, and attains purity of consciousness it automatically reveals infinite knowledge and infinite energy which were inherent in it all the time. Karma, good or bad and indifferent is alien to the true nature of the soul, and is the cause of its bondage from which emancipation is sought. From this point of view, therefore, the difference between good and bad deeds is only one of degree and not of kind.

We have now to see how an ethical system was evolved out of this self-centred doctrine.

Emancipation is the goal and right faith (darshana), knowledge (jnana), and conduct (charitra) constitute the path leading up to it.

A knowledge of the self cannot however, be obtained through the senses or by logical methods, nor can it be worked out from accepted articles of faith. It is a matter of direct experience which at first gives a vision or glimpse of Reality (darsana) and the full view (Jnana) is obtained after discipline and meditation. One, who is blessed with this vision either already possesses, or acquires automatically, eight cardinal virtues which are the constituents (angas) of right faith:

freedom from fear freedom from desire freedom from disgust or hatred covering up the defects of others' and suppressing one's own evil nature self-less love of the maternal type for all living things freedom from superstition confirming others and oneself in the right faith proclaiming the glory of true faith

The first five are the primary virtues and the remaining three only derivative ones.

- True faith should give freedom from fear in this world and the next. Realising the true nature of the self, the individual feels that he has conquered suffering. He acquires self-confidence, which in view of the Jain conception of the self is equivalent to trust in god.

- Freedom from desire when translated into a vow becomes a vow of poverty in the case of a recluse and of contentment in the case of a layman. The Jain view goes further in that it requires not merely contentment with what one has, but also a voluntary restriction of possessions within one's reach (parigraha parimana).

- Freedom from hatred or disgust is interpreted by Jainism in a rather wide sense. Stress is laid in discussing this trait on the absence of all kinds of pride including spiritual pride. But it also extends to inanimate objects which may cause annoyance by behaving according to their nature. Humility, patience and forbearance taken together will express the idea.

- Covering up others' defects and suppressing one's own would be, equivalent to charity of disposition and self-purification.

- 'Love of the maternal type' self-less, devoted and free from passion requires no explanation.

To put it in brief, the virtues which Jainism inculcates and expects to result directly from true religion are faith, contentment, patience, forbearance, humility, charity, purity, and love. It is interesting to observe that the west regards these virtues as peculiarly Christian, but they were laid down in India systematically as the very foundation of religion at least 500 years before Christ.

It has been explained what true faith is at its brightest. Faith, knowledge and conduct are however developed not after one another but pari passu. They help each other's growth. At the final stage the three become identified.

Faith gives a partial view of reality and knowledge a fuller view but at the stage of perfection the question of degree does not arise. At this stage the self functions as pure consciousness which is the right conduct for it. Until, however, one sees light for oneself, an account of reality has to be accepted on the authority of the seer; knowledge of his word has to be cultivated, and conduct regulated accordingly. This is conventional (vyovaharik) religion. Disciplined conduct coupled with meditation may lead to a direct vision of reality, but not necessarily. On the other hand such a vision may come all of a sudden even to a sinner as a spontaneous (naisargik) development. This is the Jaina counterpart of the doctrine of grace in the theistic systems.

The most important part of discipline is the observance of the five principal vows which have already been mentioned. They have to be observed in thought, word and deed, (mana, vachana, kāya), and they cover deeds done by oneself or abetted or approved in others (krita, karita, anumodana). There are subsidiary vows for laymen aiming at restriction of desire in various directions. The recluse has also to observe five conditions in walking, speaking, eating, handling things and attending to bodily functions and three controls of mind, speech and body. Other duties to be performed by a recluse at the earlier stages of his career are:

- repentance including confession and expiation,

- renunciation,

- worship,

- meditation in solitude,

- practising physical endurance.

The general outline and technique of the Jaina ethical system resemble those of Christianity, but in one respect there is a radical difference between the two. The Jaina vow of ahimsa extends to all forms of life, but varying degrees of laxity are permitted in the case of laymen. The corresponding Christian commandment, though worded generally enough, is restricted in application to human beings. As modern civilisation has become practically identified with Christendom, modern sentiment adopts an attitude of frank selfishness towards animals and makes them entirely subservient to the needs of man. Animals may be killed for food, for pleasure, for sport, for gain, even for satisfying whims and fancies in personal decoration. They may be subjected to torture for the advancement of scientific knowledge. A conflict is noticeable in the heart of the average modern man in this respect. The gourmand who relishes meat dishes at table may feel sickened at the sight of an animal being slaughtered. A sportsman who likes to count his bag at a duckshoot by the hundred, may take no end of trouble in tending a maimed bird. Many sportsmen have confessed to feeling a pang when picking up the limp and pathetic looking carcase of a creature which looked lively, happy and carefree only a minute before. Such human promptings are, however, stifled as unmanly. The West may yet learn a lesson from India in this direction.

Jagat Prasad

Jagat Prasad