A Shatrunjaya 'Tirtha Pata'

A Monumental Jain Pilgrimage Painting in the Ethnographic Museum, Antwerp, Belgium

Elsje Janssen and Françoise Therry

ABSTRACT:

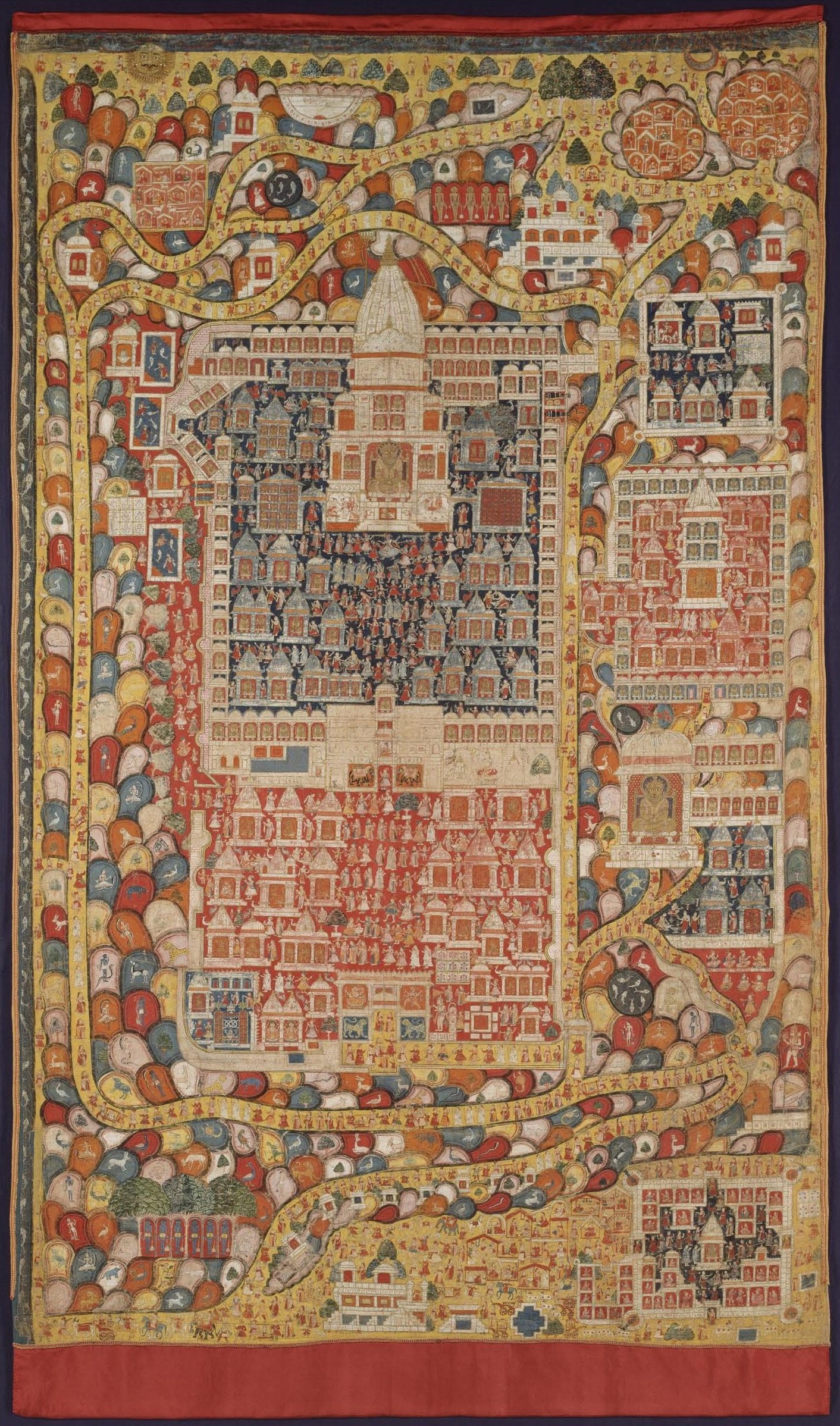

This 'tirtha pata' or pilgrimage painting depicts in bird's-eye view the most sacred of all Jain pilgrimage sites, the holy mountain of Shatrunjaya, near Palitana in Gujarat, India. Once a year this kind of topographical painting is displayed at a temple or other suitable location for devotees to worship. This serves as a surrogate for those unable to make the pilgrimage to the site itself. It is evident from the damage it has suffered that this 'pata' has a history of intensive use. Dismantling the 'pata' revealed fragments of earlier borders and lining, as well as parts of the painting that had been sewn into the binding of the left and right edges. This binding was reconstructed in such as way as to make the entire painting visible once more. The badly deformed cloth was relaxed with cold steam. Abrasion to the surface paint layer gave the 'pata' more the feel of a textile than a painted canvas. Therefore it was decided to consolidate the holes by a sewing technique, rather than the more traditional Indian method of backing them with canvas applied with starch adhesive.

Introduction

This 'tirtha pata' or pilgrimage painting, a monumental Jain pilgrimage painting in the collection of the Ethnographic Museum of Antwerp, in Belgium (Figure 1) depicts in bird's-eye view the most sacred of all Jain pilgrimage sites, the holy mountain of Shatrunjaya, near Palitana in Gujarat, India. Just as every Muslim aspires to visit Mecca, so every Jain expects to pay a visit to Shatrunjaya at least once. Unlike the Muslims, however, the Jains have an alternative for those unable to make the pilgrimage: a topographical painting of the site serves as a surrogate. Once a year such paintings are displayed at a temple or other suitable location for devotees to worship. The paintings are usually of colossal size, so the details can be seen without difficulty.

Background

Jainism is a non-theistic Indian faith based, most immediately, on the teachings of Mahavira (599-527 BCE), a contemporary of the Buddha. According to Jain belief, however, the religion was founded millennia earlier by Rishabhadeva, the first of a series of twenty-four Jinas, or spiritual leaders. Jainism shares concepts with Buddhism but is a separate religious path. Its most important teaching is non-injury to living creatures. It prescribes asceticism, meditation and strict vegetarianism in order to attain liberation from the cycle of rebirth.

Figure 1:

The 'tirtha pata', a monumental Jain pilgrimage painting in the Ethnographic Museum of Antwerp, in Belgium. After treatment. © Ethnographic Museum, Antwerp, Belgium, AE 97.60, c. 1875, 342 x 194 cm. Photo credit: Collectiebeleid, Bart Huysmans.With some six million adherents worldwide, Jainism is one of the smallest of the major world religions. Even so, Jains have been a significant force in Indian culture, contributing through the centuries to philosophy, art, architecture and sciences, and last but not least the politics of non-violence advocated by Mahatma Gandhi.

In Jain thought the four qualities of the higher self are analogous to the four conditions of canvas as it undergoes the stages of preparation necessary for painting: it should be washed, burnished, drawn upon and coloured. Before being painted, the canvas is primed with a coat of wheat flour or tamarind-seed paste. Once dry, this ground is burnished to give a smooth surface for the drawing and painting. The preliminary drawing is usually made in a vivid red, then the rest of the colours are applied, including gold or silver. The painting is completed with the inscribing of mystic syllables. Some patas have additional symbols drawn in red on the reverse, making them more sacred still.

Conservation

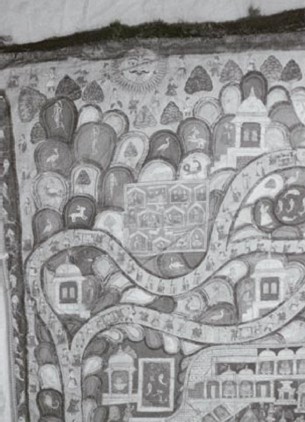

It can be deduced from the damage to this pilgrimage painting that it has been subject to quite intensive use before entering the museum collection. It had been repeatedly repaired (Figure 2) and the original lining had been replaced by a much heavier one. What the original method of hanging or fixing the 'pata' may have been, we can only speculate.

In one of its most recent periods of use it was clearly hung and fixed in a rather rudimentary way with nails, lengths of string and braid loops. The present braid used to bind the left and right edges of the 'pata' was not original. Beneath it were the remains of an earlier, finer binding (Figure 3).

Figure 2:

It can be deduced from the damage to this pilgrimage picture that it has been subject to quite intensive use. It had been repeatedly repaired and the original lining had been replaced by a much heavier one. What the original method of hanging or fixing the ‘pata’ may have been, we can only speculate.

Figure 3:

In one of its most recent periods of use it was clearly hung and fixed in a rather rudimentary way with nails, lengths of string and braid loops. The present braid used to bind the left and right edges of the ‘pata’ was not original. Beneath it were the remains of an earlier, finer binding.

Figure 4:

Several roughly mended rips and triangular tears marred the painting.

Hanging had deformed its upper corners to such an extent that the bottom part of the painting was also affected, and the cloth was no longer flat.Figure 5:

The ragged edges of the cloth had been sewn into this earlier binding, so that part of the image was concealed. Once the ‘pata’ had been completely dismantled it was possible to reconstruct the partly hidden Shatrunjaya River on the right hand side of the picture and a procession of pilgrims making their way along a road on the left.

Several roughly mended rips and triangular tears marred the painting (Figure 4). Hanging had deformed its upper corners to such an extent that the bottom part of the painting was also affected, and the cloth was no longer flat.

The ragged edges of the cloth had been sewn into this earlier binding, so that part of the image was concealed. Once the 'pata' had been completely dismantled it was possible to reconstruct the partly hidden Shatrunjaya River on the right hand side of the picture and a procession of pilgrims making their way along a road on the left (Figure 5).

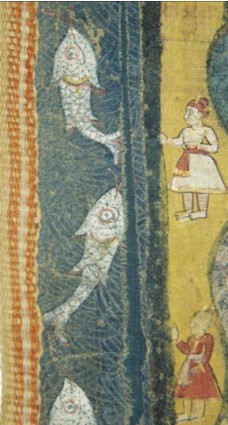

With the exception of the central part of the 'pata', the harder surface paint layer is largely abraded, though the picture is still very legible. This gives the cloth more the feel of a supple printed textile than of a stiff painted canvas (Figure 6). Therefore it was decided to consolidate the rents and holes in the 'pata' by a sewing technique, rather than backing them with canvas applied with starch adhesive - the method traditionally used for repairing damage of this kind in India.

Once dismantled, the cloth was relaxed with cold steam. The tears were locally fixed on a linen batiste support by couching in two-ply silk. The original silk tablet weave border along the top edge of the 'pata' was protected in a silk muslin sleeve. New borders in red silk pongee were applied to the top and bottom of the 'pata': the exact width could be deduced from the remaining fragments (Figure 7).

With the exception of the central part of the ‘pata’ the harder surface paint layer is largely abraded, though the picture is still very legible. This gives the cloth more the feel of a supple printed textile than a stiff painted canvas. Therefore it was decided to consolidate the rents and holes in the ‘pata’ by a sewing technique, rather than backing them with canvas applied with starch adhesive - the method traditionally used for repairing damage of this kind in India.

Figure 7:

Once dismantled, the cloth was relaxed with cold steam. The tears were locally fixed on a linen batiste support by couching in two-ply silk. The original silk tablet weave border along the top edge of the ‘pata’ was protected in a silk muslin sleeve. New borders in red silk pongee were applied to the top and bottom of the ‘pata’: the exact width could be deduced from the remaining fragments. A new, lighter lining in dyed linen batiste was sewn in place along the top edge, together with a narrow strip of Velcro for hanging. The braid used for the earlier binding was sewn back in place, though without catching in the new lining. The conserved ‘tirtha pata’ was displayed on a slightly sloping panel that was padded and clad with linen. The use of a sewing technique to consolidate the damaged areas allows the cloth to be rolled, thus taking up much less space in the reserve.

A new, lighter lining in dyed linen batiste was sewn in place along the top edge, together with a narrow strip of Velcro for hanging.The braid used for the earlier binding was sewn back in place, though without catching in the new lining. The conserved 'tirtha pata' was displayed on a slightly sloping panel that was padded and clad with linen.

The use of a sewing technique to consolidate the damaged areas allows the cloth to be rolled, thus taking up much less space in storage.

References

S. Andare, 2000, 'Jain Monumental Painting', in: Exhibit Catalogue Etnografisch Museum Antwerpen, Steps to Liberation, 2,500 Years of Jain Art and Religion (Museum Antwerpen: Antwerpen).

Wikipedia, 'Jainism': http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jainism. Accessed February 2009.

BIOGRAPHIES:

Elsje Janssen is an art historian, trained as a textile conservator. She is currently the Head of Collection Policy / Conservation and Management, Department of Museums, Conservation Libraries and Heritage, City of Antwerpen, Belgium.

Françoise Therry is formerly the textile conservator working in the Ethnographic Museum in Antwerp, Belgium. She now works at the Africa Museum in Tervuren, Belgium.

CONTACT:

Elsje Janssen, Collectiebeleid, Behoud en Beheer, Hessenhuis, Falconrui 53, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium. E-mail: .

Proceedings of the Forum on the Conservation of Thangkas Special Session of the ICOM-CC 15th Triennial Conference, New Delhi, India, September 26, 2008

Hosted by the Working Group on Ethnographic Collections, the Textiles Working Group and the Paintings Working Group

Editors: Mary Ballard and Carole Dignard Published by the International Council of Museums - Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC) © ICOM-CC 2009

Disclaimer

These conference session papers are published and distributed by the International Council of Museums - Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC), with authorization from the copyright holders. They are published as a service to the world cultural heritage community and are not necessarily reflective of the policies, practices, or opinions of the ICOM-CC.

Information on methods and materials, as well as mention of a product or company, are provided only to assist the reader,

and do not in any way imply endorsement by the ICOM-CC.