Hinduwebsite.com

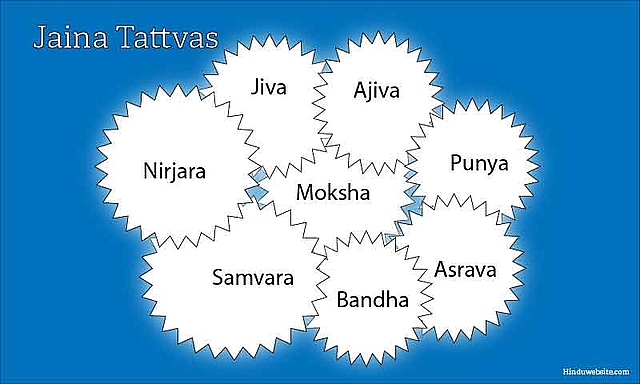

The essential doctrine of Jainism centers around tattvas, loosely translated into English as basis substances, truths or realities, which are described in the Tattvardtha Sutra. The doctrine of tattva is common to Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism and several schools of Indian philosophy. However, they differ with regard to the nature, number and composition of the tattvas. For example, Samkhya recognizes 24 tattvas while Saivism recognizes 36. In them tattvas are essentially parts of the body or Nature such as the senses, the mind, the ego, intelligence, etc. In Hinduism, Brahman or Isvara is considered the highest and the purest tattva (suddha tattva).

Jainism follows an entirely different model. In Jainism tattvas are real substances or entities, which are uncreated. They are responsible for various states or conditions in which the individual Souls exist, not mere theoretical building blocks or bodily parts. The number of tattvas are also comparatively few. The Digambaras recognize seven tattvas while the Svetambaras recognize nine.

There is no concept of tattva in western religions or philosophy. Translating it as a substance or reality does not make much sense to those who are not familiar with the term. We may speak of a it as a material manifestation, or a key ingredient of the world in which we live. Since many of the tattvas mentioned here are difficult to translate, the original Sanskrit words and their English equivalents are used in this discussion.

According to Jaina beliefs, a tattva is a basic, and ultimate reality that represents an aspect of existence. In itself it is incomplete, but together with other tattvas it forms part of the whole existence.

All the tattvas are eternal. They may have states and modes, but they are indestructible. They are not mental constructs or metaphysical notions, as considered in some religions, but real aspects of the existence that make up the whole. It is true even with regards to tattvas such as time and Karma, They are substantial truths, not metaphysical concepts.

The seven tattvas of the Digambaras and the nine tattvas of the Svetambaras are listed in the following table.

| Digambaras | Svetambaras |

|

|

In both the lists, the first two tattvas represent the fundamental states of material existence. The rest of them are related to the conditions arising from the presence, absence or properties of Karma to which the Souls are subject. Moksa or liberation is the highest reality to which the Souls can aspire where they enjoy eternal freedom, omniscience and unending bliss.

Knowledge of the tattvas constitute right knowledge. Their knowledge plays a vital role in the liberation of the Jivas. Hence, every follower of Jainism should be aware of them and accept them as final.

God

Another noticeable feature of the Jain tattvas is the absence of God (Isvar) tattva. Jainas discount any notion of a Universal Supreme Self or a creator God as the source of all manifestation. They accept the diversity of the world as is, without attributing it to a singular and ultimate cause. For them, matter (dravya) in its numerous forms is true and eternal, and responsible for diversity and modifications.

Although Jainism recognizes matter as the ultimate reality and refutes all notions of an immaterial, stateless and transcendental Self, we cannot equate Jainism with the atheism of the West or the materialism of the Carvakas because it believes in the eternal and spiritual nature of the individual Souls and their liberation.

For Jainism the individual Souls are as real and material as the individual beings. They represent the same ultimate and eternal reality under different condition. A soul always has a body, size and shape, made up of molecules or atoms of varying frequencies. In bound state it is gross and in liberated state it is subtle. It does not recognize a universal God, but it certainly affirms the existence of gods and perfect beings and in the possibility of each individual soul growing into a godhead through austere self-effort, self-purification and final liberation from the cycle of births and deaths.

An omniscient soul is nothing less than a God, all powerful, all capable and all knowing, but not concerned with the creation, preservation and destruction of world, which are processes inherent in existence and does not require any external force or special effort to sustain them.

The world goes through the modifications of preservation and destruction or periods of rise and fall, like waves in an ocean, but such processes are inherent to existence, with no underlying cause of causes. Even the essential realities of Dharma and Adharma in Jainism are mere mediums which facilitate actions and inactions without causing them.

For the Jainas, the soul in its omniscient state is the highest reality to which every human being should aspire to escape from the suffering and bondage which characterize their current state.

Jiva

The word jiva in Jainism denotes both a living being and an individual soul. A soul in a bound state develops a perceptible gross body and in its liberated state possesses an imperceptible subtle body. In both cases a soul has substance or matter and both are modifications of the same entity. In the bound state it has limited knowledge. acquired indirectly through the agency of the mind and its faculties, whereas in the liberated state it has direct and instant knowledge of everything through its own omniscience.

According to Jainism, a soul has also dimensions, and is subject to expansion and contraction depending upon the body it occupies. Since the soul is always larger than the body and envelops it, as the body grows and changes its size and shape with age and other conditions, the soul in it also grows and changes accordingly in proportion.

When a being dies, its soul contracts into a seed form and leaves the body. In other words, in Jainism an individual soul is a form of subtle matter packed with soul-force and very different from the Self of the Upanishads, which is constant, infinite, devoid of matter, and free from modifications and attributes.

A soul is either free or bound. In its bound state it is subject to Karma and rebirth. On earth, depending upon its Karma, a soul may be born in a mobile or immobile body. Immobile beings are usually lower organism having only the sense of touch. A good example is plants. Some beings have minute bodies called nigodas, such as the microorganisms, and may exist in clusters. Some of them may have multiple Souls. Souls may also exist in inert matter, such as water, fire, wood etc. For Jainas, who practice non-violence and do not want to hurt or harm jivas, this belief poses serious problems.

Beings are also classified depending upon the number of senses they have, such as beings having two senses, beings having three senses and so on. Beings with five senses are the most evolved. They are further divided into those which have a mind and intelligence and those without them. Some bound Souls are capable of achieving liberation through self-effort due to the quality called bhavyata, but some due to the lack of it remain forever bound to the cycle of births and deaths.

Ajiva

If Jiva is the living reality, Ajiva represents the inanimate reality. In Jaina worldview, the whole universe is made up of basically these two fundamental realities. They are like the body and soul or the day and night of existence. You cannot say that one is more important than the other because both are interdependent.

The lifeless, inert matter is called Ajiva. It is the object in relation to the individual soul or the Jiva, which is the subject. Ajiva is also substance (dravya), like other tattvas, which is subject to qualities and modifications. It is found in two basic modes, with form (rupa) and without form (arupa).

Arupa dravyas (substances) are divided into dharma, adharma, space, and time. There is only one rupa dravya called pudgala, made up of atoms and molecules. It is the clay of existence found ubiquitously in all perceptible objects, bodies and their parts.

Dharma dravya is the principle of motion, without qualities. It is the "medium of movment for the objects, like water, although not its cause." Adharma drayva is the principle of rest. It is also devoid of qualities and acts as the medium of rest, like the shadow, but not its cause.

Both Dharma and Adharma have none of the properties of matter, but they are self-sustaining universal realities in which beings and objects are able to move and rest according to their own qualities.

Space (Akasa) provides the field for other substances to exist, while Dharma and Adharma make it possible for them to move and rest in it. Space is an all pervading and infinite reality. It consists of both the space in which the worlds exist (lokakasa) and the space beyond it (alokakasa), which is perceptible only to the omniscient perfect beings. The former (lokakasa) is further subdivided into different regions depending upon which world exists in it.

Time is another fundamental reality which supports all the changes and modifications to which both a Jiva and Ajiva are subject, without causing them. Modifications to Jiva and Ajiva happen because of the mere presence of time, which can be measured in units of time. However, time is not their cause. Just as the stone under a potter's wheel supports the potter's actions, it facilitates changes but not causes them.

Time has existence (astitva) but no formation (kayatva). Although it consists of endless points arranged linearly, only the present moment is perceptible to the beings and the rest become past and future to them. Time has also two distinct aspects, an infinite aspect (Kala), which is without a beginning and an end and immeasurable, and a finite aspect (Samaya), which has a beginning and an end, and which can be measured in units of time such as seconds and hours etc. In Jainism, as in Hinduism, Time is considered cyclical (cakra). It is also described as death and destroyer because until they achieve liberation, the jivas are subject to death and rebirth at specific points of time.

Pudgala is the matter that is perceptible to the senses and manifests as bodies, bodily parts, sense-objects, physical mind, and Karma substance. It is made up of fine particles called atoms (paramanu), which are invisible to the naked eye, but together as aggregates make up the various objects, organs, bodies and things. Pudgalas may exist as atoms (anus) or in aggregate forms (skandas).

The atoms of Pudgala have the power to attract and repel. Their movement, rest and aggregation are made possible by Dharma, Adharma and Space. Unlike other tattvas, Pudgalas and the atoms that are present in it, have the qualities of smell, taste, color and touch. Each of the qualities have further subtle nuances and variations such good and bad, bright and dark, hot and cold, sweet and sour etc. Based on their aggregation, Pudgalas are of six types. super fine (suksmatisuksma), fine (suksma), slightly gross (suksma-sthual), moderately gross (sthula-suksma), gross (sthula), and very gross (sthula-sthual). One may also see in a Pudgala various conditions such as light, darkness, shadow and sound due to the activity of the atoms present in it.

Asrava

Asrava refers to the influx of Karma. According to Jainism, Karma is a substance having materiality (pudglalika). It is not a mere effect or consequence as believed in Hinduism and Buddhism. Each soul bound to the cycle of births and deaths is penetrated by this substance because of its actions and movements. It results in the formation of a casual body (karmasarira) in each soul, which remains clung to it until its liberation. Every action and inaction of a being results in the inflow of Karma, which covers the intelligence and omniscience of the soul.

Jaina philosophers identify five causes for the influx of Karma, namely delusion or false belief (midhyatva), indulgence in pleasures (avirati), carelessness (pramada), worldiness (kashay), and actions of the mind and body (yoga). They also recognize 8 main types of root Karmas (mula prakriti), depending upon what they cover or influence and 148 derivative Karmas (uttara prakriti).

The eight main Karmas are: actions which conceal knowledge (jnanavarana-Karma), actions which conceal sight and insight(darasanavara), actions which create feelings of attraction and aversion (vedaniya), actions which lead to delusion (mohaniya), actions which influence lifespan (ayuh), actions which influence an individual's name and form (nama), actions which influence a person's lineage and birth (gotra), and actions which obstruct the soul from knowing and becoming free (antaraya).

Punya

Punya is the fruit of good actions. It is loosely translated as virtue. According to Jaina scriptures, Punya is the result of right conduct (Charitra) arising from right knowledge (Jnana), faith (Sraddha) and supreme effort. Faith should be rooted in love (Anuraga) for the good and supreme effort in the will to do (Virya).

In other words, Punya arises from virtuous actions performed with knowledge, intelligence, faith, love and resolve. By constantly performing right actions, a soul gradually transforms from within both mentally and physically.

Jaina tradition identifies nine general ways in which one can perform good actions and earn Punya. They are: by feeding the hungry, by quenching the thirst of the thirsty, by clothing the poor and destitute who cannot afford clothing, by sheltering the homeless, by providing seats and bedding to those who are tired and weary, by paying respects to the pious and the venerable, by attending to the needs of those who need it, and by bowing to the elderly and virtuous people.

Good actions do not by themselves liberate a soul, but create favorable conditions for its enjoyment, peace and happiness in the form of a good birth as a human being in a good family or as a god in the world of gods, with a well proportioned body and pleasant disposition.

Earning Punya is not a solution to the problem of bondage. Punya binds the soul to the world just as Papa is. Therefore, eventually a Jaina monk rises above both and strives for salvation to get rid of all good and bad Karmas entirely.

Papa

Papa is the fruit of evil and sinful actions. It is loosely translated as vice directly attributed to passions and negative emotions due to lack of right knowledge and moral strength. If Punya arises from voluntarily choosing to perform good actions and or avoiding bad actions, Papa arises from voluntarily choosing to perform bad actions and or avoiding good actions.

In both cases the determining factors are the voluntary actions performed by the soul and the choices it makes willingly. In general, delusion (mithyatva) and evil intentions (duhsilatva) result in evil actions.

Jaina ethics identify 18 types of actions which result in Papa. They include, cruelty to animals (jiva himsa), untruthfulness (asatya), stealing (adattadan), unchastity (abrahmacarya), covetousness (aparigraha), anger (krodha), egoism (man), deceit and hypocrisy (maya), greed (lobha), attraction or attachment (raga), aversion (dvesa), afflictions (klesa), slander (abhyaksana), making up things (Paisunya), willful indulgence in pleasure and pain (rati and arati), misleading actions (maya mrisa), mistaken notions and perceptions (mithya darsana). These eighteen types of actions result in 82 kinds of Karma which bind the soul to the cycle of births and deaths.

Bandha

Bandha means binding or the entanglement of the Jiva with the various inert substances (Ajiva), whereby both begin to look as one, as in case of milk and water. It is caused by the influx of Karma into the soul according to its deeds, whereby it becomes bound to certain states and modes, such as ignorance, delusion (mythyatva), growing, aging, sickness, birth, death and rebirth, and loses sight of its omniscience and blissful nature.

As long as the karmic matter is bound to them, the Souls are subject to the cycle of births and deaths (samsara) and the fruit of their actions. Bound to their bodies and the karmic matter, they continue their existence in various states of delusion and impurity with limited knowledge and capability.

The Souls are bound according to the type of Karma that flows into them. Such bondage arising from the influx of Karma is both subjective (bhava) and objective (draya). Subjective bondage arises from the attachment to feeling of individuality or ego and objective bondage from attachment to material things. Depending upon the how Karma may coalesce with the soul, bondage is classified into four kinds.

- Prakriti bhanda:

This arises from Karma prakritis, or actions that are both injurious and non-injurious to the soul, effecting its vision, knowledge, status and birth. - Sthiti bhanda:

This is the bondage which arises in relation to the duration for which a Karma may stick to the Soul. Some Karma matters falls away, while some take much longer time to fall off. - Anubhaga bandha:

This is bondage arising from actions that sharply impact the nature and character of an individual and leave strong impressions that are difficult to erase. - Pradesha bandha:

This is the bondage with references to specific places in the soul where Karma may accumulate and influence its course of existence.

Samvara

The first step in ending the bondage of Souls and its release from the cycle of births and deaths so that the Self will return to its state of omniscience and self-rule (swaraj) is to stop the influx of Karma into the soul. This state is called samvara.

It can be practiced either subjectively by living virtuously, observing the vows and moral precepts or objectively by shutting down the channels of Karma through which it flows into the soul.

Jaina texts prescribe 57 kinds of Samvara divided into five Samitis, three Guptis, ten Yati-dharmas, twleve Bhavanas, 26 Parisahas, and five Charitras.

Samitis are the voluntary movements or actions of a Jiva practiced according to the scriptures or ordained laws such as careful walking, careful movements of the tongue, careful eating etc.

The Guptis are actions performed to control the inner nature of a jiva, such as restraining the mind, restraining sorrowful thoughts, cultivating equanimity, introspection, controlling speech etc.

Yati-dharmas are the duties of a monk, which are ten, namely forgiveness, humility, simplicity, absence of greed, austerity, restraint, truthfulness, purity, renunciation, and chastity.

Bhavanas are mental states brought by contemplation within oneself upon certain aspects of reality or existence such as impermanence, helplessness of the soul, nature of the world, aloneness of the soul, the distinction between the soul and the body, influx of the Karma etc. the

Parihasas refer to the endurance of various kinds of hardships a seeker of liberation voluntarily undergoes to stop the influx of Karma and purify himself, such as endurance of hardship arising from hunger, thirst, cold, heat, insect bites, nakedness, presence of opposite sex, taunts and insults, personal injury, sleeplessness, thorns etc.

Charitras are rules of conduct, which a Jaina has to practice to arrest the flow of karmic influx, such as abandoning relationship with bad characters and retiring into seclusion, confessing one's sins to a teacher or master, purifying the heart and the mind by serving the monks who are engaged in austerity, cultivating indifference to worldly things and staying in the present guarding against harmful thoughts in a reflective and introspective state.

These various types of actions, restraints and observances gradually arrest the influx of Karma into the soul and enable the jiva to progress on the path of liberation and self-purification

Nirjara

Nirjara means completely washing away or removing the karmic matter present in the soul whereby the casual body, the outer covering, which is responsible for the rebirth is complete disintegrated and destroyed.

According to Jaina texts, it can be accomplished in two ways: passively by allowing the Karma to exhaust themselves and actively by practicing penances, and austerities and observing all the vows prescribed in the scriptures. The former is known as akama nirjara and the latter sakama nirjara.

Akama nirjara is impractical because Asrava or the inflow of Karma into the Soul is continuous and does not stop on its own, since it is impossible to remain alive without performing any action. While some Karmas may become extinct by themselves, some old Karma may not fructify at all in this life and will be carried forward. At the same time, new Karmas keep flowing in due to the actions performed in the present life.

Depending upon how Karmas accumulate and fructify in the souls, in Jainism, as in Hinduism, Karma is classified into four kinds: Satta Karma, which is the entire latent Karma of the past accumulated and present in the soul, Bandha Karma, is the Karma that accumulates in the soul in the current life and will fructify in future, Udaya Karma is the Karma that is apportioned to the being at the beginning of its life and will fructify during the current life shaping its destiny, and Udirana Karma, which will fructify by the effort and will of the individual bedore they are destined to fructify.

Thus, we can see that Akama Nirjara will not help the soul at all to remove all Karmas and is not a wise approach. The right approach is to practice Sakama Nirjara or active cleansing by burning up the karmic seeds through austerities, which are again of two types, external austerities (bahya tapah) and internal austerities (antar tapah). The former is useful in cleansing the physical body and the latter in cleansing the mind.

Exterior austerities are performed in six ways: by fasting (Anushan Vrata) to purify the senses, by avoiding full meals (Unodori) to remove inertial and laziness, by putting certain dietetic restrictions on (Vritti Sankhepa) the quantity, duration, frequency, and number of food items one may eat to cultivate restraint and will power, by renouncing tasty food items (rasatyaga) to cultivate detachment, by enduring physical pain and discomfort (Kayaklesa) towards the dualities of life such as heat and cold to cultivate sameness, and by withdrawing the mind from the sense objects (Samalinata) to cultivate the spirit of renunciation. These six austerities help in cleansing the body of the accumulated Karma.

Interior austerities performed internally are also of six types: by penance and repentance (Prayaschitta) for the mistakes made in the past due to negligence or carelessness, by cultivating humility and right conduct (Vinaya) towards ascetics, elders, scholars, saints, teachers etc., by serving the humanity (Vaiyavritya), especially the ascetics, the poor and helpless, by feeding them, sheltering them and helping them in other ways to reduce their suffering, by studying the scriptures (svadhyaya), contemplating upon the truths in them and practising them, by cultivating discrimination (Vyutsarga) between Jiva and Ajiva and right and wrong, and by contemplating (Dhyana) upon an object, image, thought or idea.

Jain tradition recognizes four types of Dhyana: Arta, Roudra, Dharma and Sukla. Arta Dhyana is contemplation upon an object of enjoyment. Roudra Dhyana is contemplation upon those objects and memories which create feelings of anger and vengeance. Dharma Dhyana is contemplation upon the nature of the inner Self. Finally, Sukla Dhyana is contemplation upon the purity of the soul.

Samvara and Nirjara are not mutually exclusive, but complimentary. They should be practiced simultaneously, hastening the process of liberation. They are the means by which a Jiva takes control of his destiny and works for his liberation, without leaving to chance or fate. Similarly both have to be practiced with regard to not only bad Karma (papam) but also good Karma (punya) because Karma of every kind and in every form should be removed from soul for it to be free.

Moksha

In Jainism, Moksha means complete liberation, or emancipation of the individual soul by from all the accumulated Karma, both good and bad, by arresting the its inflow and removing every trace of it.

Unlike in Hinduism, it is not attained by performing dutiful actions, or desireless actions or by acquiring knowledge but only by removing physically all the Karma from the soul.

Similarly, unlike in Buddhism it is not attained by ethical living. It is attained only when the Soul regains its purity, omniscience and perfection by getting rid of all the Karma and its bonds (Karma-pasa).

Jaina texts refer to two types of liberation: mental (bhava) and physical (dravya). Mental liberation arises when the soul is freed from the four types of Karmas that injure the soul (Ghatiya Karma), which are mentioned before. Physical liberation arises when the soul is freed from Karmas that do not injure the soul but influence its destiny (Aghatiya Karma).

With the mental liberation, the soul is freed from the impurities that cover its omniscience (Kevala Jnana). From the physical liberation, it experiences eternal bliss. With the eternal and pures state of omniscience and with endless delight in itself, the soul finally attains complete liberation (Moksha) and escapes from the snares of birth and death. In that state it goes upwards into the highest sphere of Lokakasa and enters the region (Siddhasila) where free and perfect Souls reside. In that state a being has the same form as the humans upon earth, with Right Knowledge, Right Vision and Right Conduct, but without the grossness of the human body.

Moksha is the ultimate and highest goal for the Jivas caught in the moral world. Moksha is the highest and ultimate reality where a Soul returns to its perfection and omniscience.

Jayaram V

Jayaram V