Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

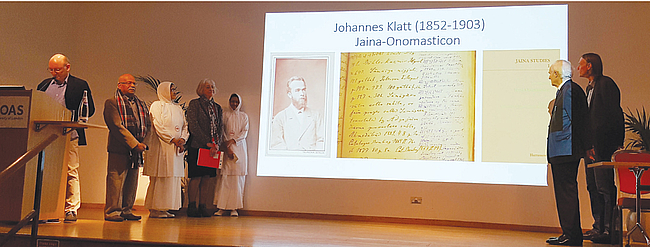

The 17th Annual Jaina Lecture and Jainism and Buddhism, the 19th Jaina Studies Workshop, took place at SOAS on 17-18 March 2017. The Lecture and Workshop were co-hosted by the Centre of Jaina Studies and the SOAS Centre of Buddhist Studies, with generous additional support from the V&A Jain Art Fund, and the Jivdaya Foundation in Dallas.

17th Annual Jaina Lecture

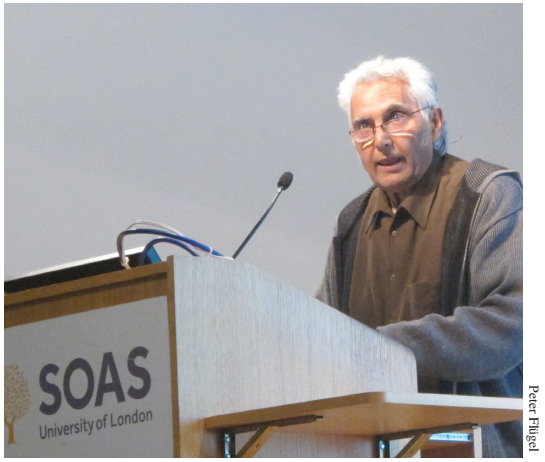

Sin Fujinaga (Miyakonojō Kōsen)

The proceedings commenced with the ceremonial Launch of Johannes Klatt's Jaina-Onomasticon. Thereafter, Sin Fujinaga (Miyakonjō Kōsen, Japan) delivered the 17th Annual Jaina Lecture on 'Nidāna: A World with Different Meaning'. Investigating the concept of nidāna within the wider Indian philosophical context, he showed that it is used in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. The term 'nidāna' is used in the sense of 'cause' in Buddhism, whereas in Jainism it holds a specific meaning, namely, the 'bartering of penance'. Fujjinaga noted that a Buddhist text, the Suttanipāta, offers the oldest use of nidāna, designating a cause that evokes lust and hatred. He referred especially to the Mahānidānasutta, a dialogue between Ānanda and the Buddha about dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda). In this text the Buddha is said to have anticipated diverse perspectives about nidāna, such as cause (hetu), origin (samudaya), and source (paccaya). Fujinaga then discussed the application of the term nidāna in early Jaina texts such as the Ācārāṅgasūtra and the Uttarādhyana-sūtra. In a former text (ĀS I.6.1.2), nidāna refers to something which obstructs the way to liberation. The commentator Śīlāṅka construes this term as 'upādānaṃ karman'. Fujinaga gave the term upādāna used in Buddhism a slightly different meaning: 'a special cause of reincarnation'. He noted that in other parts of the Ācārāṅga, commented on by Śīlāṅka (ĀS I.4.3.3; I.8.1.4), the term nidāna appears twice with a negative prefix 'a' in the same phrase a-nidāṇa ('aniyāṇā'). In this context nidāna designates something which causes adverse effects, especially passions such as anger. He noted that an early Jaina canonical text, the Uttarādhyana-sūtra, narrates in the thirteenth chapter the story of Citta and Saṃbhūta. This story is very important for illustrating how nidāna can be effective in enabling a series of desired reincarnations. The idea of nidāna in this context could be regarded as a cause which leads to rebirths. Moreover, the Ācāradasāḥ, an earlier canonical text and originally the second part of Ācārāṅga-sūtra, describes nidāna in the tenth chapter with regard to ten stories. Of these, the first nine are concerned with nidāna and the tenth narrates a-nidāna. The first and second stories depict Jaina monks and nuns. In the first story King Śrenika and his queen Cellaṇā are depicted as leading a happy life with opulent ornaments and many attendants. Observing this, some Jaina mendicants thought, 'If there is a special boon for penance, regulation, chastity and perseverance, then we will also experience various luxuries of human beings in another life. How wonderful!' In the story, Mahāvīra refers to such thoughts as nidāna. He further elaborates that such mendicants, having entertained such thoughts without confession and atonement, will be born as gods or reincarnate as members of noble families. However, they will not be able to imbibe dharma. In the third story, a monk worries about his life as a male and wishes to be born as a female, whilst in the fourth story a nun expresses the difficulties of being a woman and desires to be a male. Such wishes and desires are also called nidāna, because without confession or atonement, even though they may bring about rebirth as a god or a goddess who enjoys life in heaven, they will be unable to hear and comprehend the preaching of the omniscient ones. These examples suggest that the idea of nidāna was meant to encompass all followers of Jainism, both ascetics and laypersons. Fujinaga had briefly investigated this concept in Buddhism, and in Śvetāmbara Jaina texts. He suggested, however, that there may be more evidence about the concept of nidāna available in Digambara texts such as the Ṣaṭkaṇḍāgama and its commentaries. Fujinaga noted that the concept is not used in Hinduism at all.

Launch of Johannes Klatt's Jaina-Onomasticon, Peter Flügel, Hampana Nagarajaiah, Samaṇī Pratibhā Prajñā, Renate Söhnen-Thieme, Samaṇī Unnata Prajñā, J. Clifford Wright, Kornelius Krümpelmann.

Workshop: Jainism and Buddhism

The first session of the 19th Jaina Studies Workshop commenced on 18 March 2017, and was chaired by Vincent Tournier (SOAS Centre of Buddhist Studies). The first paper was read by Charles DiSimone (LudwigMaximilians-Universität München, Germany) who spoke on the Mūlasarvāstivāda Dīrghāgama Manuscript Found at Gilgit that Deals with Jainism in the Eyes of the Buddhist. He mentioned that collections that were lost for centuries were found at Gilgit, which is on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan. These findings are known as Dīrghāgama, which are a 'collections of long discourses', comprising 47 fragmented texts. They are analogous to the Dīghanikāya of the Theravāda Buddhist tradition. The focus of the presentation was a depiction of Mahāvīra's death (jñātaputra nirvāṇa) and a discussion of his teachings, including the understanding and misunderstandings of his disciples. The Prāsadika-sūtra narrates about Mahāvīra's demise followed by a split and dispute among his disciples. According to the Buddhist view, an ill proclaimed doctrine is not praiseworthy. Only the Buddhist doctrine are considered complete and beyond doubt, and even after the Buddha passed away, they are praiseworthy. DiSimone concludes that based on the nature of manuscripts, during the time of the composition of the Dīrghāgama there was no actual debate with any religious opponents (anyatīrthika). Hypothetically, the narrative served as a means of proselytization and legitimizing Buddhist doctrine.

Juan Wu (University of Leiden)

The second paper was by Christopher Key Chapple (Loyola Marymount University, USA) on The Conversion of Jaina Women to the Buddhist Path According to the Pali Canon. The Therῑgāthā provides accounts of early Jaina nuns who were influenced by Buddhist teachers and converted to Buddhism. Such tales of conversion are not available in Jaina canonical texts. Chapple cited two stories of ladies who had been members of Jaina religious orders before converting to Buddhism. The first woman was Bhaddā Kuṇḍalakesā, who was born into a 'financier's' family and trained as a Jaina nun. She eventually became proficient at debating, travelling from village to village as a religious master. She was persuaded to adopt Buddhism by Sāriputra. The second nun was Nanduttarā, who was born into a Brahmin family but later became a Jaina nun. In a similar vein, she too became adept at debating, and eventually became a Buddhist nun after an encounter with Moggallāna. The paper speculated on how these two narratives characterise, from a Buddhist perspective, early conversations between Buddhists and Jainas. Chapple commented, finally, on the life-style documented, which closely resembles the norms of Jaina ascetics, such as not eating after sunset, sleeping on the ground, and so on, which are important aspects of a Jaina nun's lifestyle.

The third paper by Juan Wu (Leiden University and Tsinghua University) was entitled The Buddhist Salvation of Ajātaśatru and the Jaina Non-Salvation of Kūṇika. Ajātaśatru was considered to be a proponent of both Buddhism and Jainism. Both traditions share a common narrative that Ajātaśatru / Kūṇika, for the sake of a throne, imprisoned his father Bimbisāra / Śreṇika which led to his death. The Buddhists, however, portray Bimbisāra's death as patricide whereas the Jainas consider it to be a case of suicide. Juan Wu concluded that the Buddhist tradition is quite compassionate towards liberating Ajātaśatru from the sin of patricide and opens the door of liberation for him. In contrast, the Jaina textual tradition mentions his reincarnation in hell with no indication of future liberation.

The second session, which was chaired by Paul Dundas (University of Edinburgh), opened with Haiyan Hu-von Hinüber (University of Freiburg, Germany) who presented a paper on Ekapoṣadha and Ekamaṇḍalī: Some Comparative Notes of Jaina and Buddhist Monastic Rules. Both religions belong to the śramaṇa tradition, and they differentiate between the pauṣadha/poṣadha ceremony for the monastic members in Buddhism and those for the laity in Jainism. She mentioned that the practice of poṣadha has been an ongoing practice since the time of the historical Buddha. According to some of the early Buddhist sources such as the Aṅguttara Nikāya, the Vinayapiṭaka of the Mahāsāṃghika and the Mūlasarvāstivāda school, it is evident that the Buddhists actually adopted the poṣadha ritual from 'ascetics of different faith' (anyatīrthikaparivrājaka), among those the nigaṇṭhūposatha is explicitly referred to as the source. Comparing the above mentioned Buddhist texts with some early sources of the Jaina canon (Uttarājjhāyā, Viyāhapannati, Uvāsagadasāo, etc.), the paper discussed the usage of certain technical terms. Hinüber discussed the boundary, or ekamaṇḍalī ('in one district only'), of the group of mendicants collecting alms and eating together. Technically it is known as sambhoga in Jainism. She further discussed the required ritual immaculateness demanded of all monks or nuns staying within a maṇḍalī, who have to confess offences before taking the meal jointly. The Buddhist Vinaya, presents boundaries (sīmā) which correspond to the Jaina term maṇḍalī, and prescribes that only one uposatha / poṣadha ceremony is allowed to be held in one residence of monks, in order to guarantee the purity of the saṃgha.

The next paper of this session was read by Kazuyoshi Hotta (Otani University, Kyoto) on Corresponding Sanskrit Words of Prakrit Posaha: With Special Reference to Śrāvakācāra Texts and Buddhist Texts. He argued, on the basis of the earliest use of the term upavasatha documented in Śatapathabrāhmaṇa 1.1.1.7, that this was a purification rite practiced on the day prior to the performance of a Vedic ritual. Later on the rite of upavastha as posaha had been incorporated by Jainism and Buddhism in distinctive ways. Buddhism developed this rite mainly as a ritual for mendicants whereas Jainism employed this rite mainly as a practice for the laity. Consequently, descriptions of Jaina posaha are found in the group of texts called the Śrāvakācāra which contain codes of conduct for the laity. R. Williams states that there are several Sanskrit word-forms like pauṣadha, proṣadha, and poṣadha that correspond to the Prakrit posaha. In addition to this, the only exceptional form upoṣadhais found in editions currently in circulation. However, it is necessary to carefully consider whether this form can be traced back to the original manuscripts. Many scholars have followed R. Williams' opinion that poṣadha attained general currency, but we cannot accept this statement without qualification. Hotta argued in this presentation that the word proṣadha is most frequently used in the Śrāvakācāra texts. He referred to 52 kinds of Śrāvakācāra texts. Finally, he concluded that an important factor in this regard is the fact that Digambaras have overwhelmingly more Śrāvakacāra texts than Śvetāmbaras.

Jayandra Soni (University of Innsbruck)

The third session, chaired by Sin Fujinaga, began with Yumi Fujimoto's (Miyagi, Japan) presentation on Vasati in Vyavahārabhāṣya I-II in Comparison to Buddhist Texts. The vasati is a place where ascetics stay and used synonymously with the terms śayyā (a bedding) and upāśraya (abode, house, dwelling place, Jaina monastery). Similarly, the kṣetra can be interpreted either 'the site where a gaṇa is established' or 'the territory of a gaṇa'. Fujimoto discussed at length the rules of prohibition and execution related to staying into a vasati by Jaina ascetics. In the context of dwellings, she explained that there are some specific places such as abhiśayyā and abhiṇaiṣedhikī where monks are allowed to go in a group for svādhyāya etc. with the permission of leader. The difference between abhiśayyā and abhiṇaiṣedhikī depends on whether they spend a night there or not. When monks return to a vasati at night, the place is called abhiṇaiṣedhikī, and when monks spend a night there, the place is called abhiśayyā. Furthermore, the vasati is similar to āvāsa or vihāra mentioned in Buddhist texts, although vasati does not seem to have as many facilities as the vihāra in Buddhist texts. In conclusion, Yumi suggested that upāśraya, abhiśayyā and abhiṇaiṣedhikī can be compared with senāsanaṃ or the five kinds of leṇa,which are places to stay in the Pālivinaya. There is a difference between vasati and other places to stay, a distinction that is maintained in the Pālivinaya according to Fujimoto.

Yutaka Kawasaki (Tokyo University) presented his paper on Haribhadra's Criticism on the Concept of Possession (parigraha). In the Dhammasaṅgahaṇi, Haribhadra comments on the possession of property by Buddhist monks. He says that the possession of villages believed to contribute to the growth of the three jewels namely dhamma, buddha and saṅgha was flawed. He opines that detachment from the material world is not complete as long as ownership of properties or assets prevails, and suggests that the growth of religion can be attained only with a commitment to living without any possessions. It is customary, he suggests, for the disciples and followers to make necessary arrangements for mendicants. The focus of mendicants should not be perturbed by indulging in materialistic possessions. Thus, monks should not deviate from their goals when they have chosen to follow the path of non-attachment (aparigraha). Yutaka concluded that it is uncertain that these views were articulated by Haribhadra, even though Haribhadra did accept the principle of aparigraha.

Samani Kusum Pragya (Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, Ladnun) sent her paper on Why is the Buddha Missing in the Isibhāsiyāim? She stated that in Indian literature, Isibhāsiyāim is the only work which includes the teaching of sages from all three Indian traditionsVedic, Jaina and Buddhist. The text includes prominent figures of the Jaina tradition such as Pārśva and Mahāvīra, Vedic sages such as Yājñvalkya and Nārada, and Buddhist sages such as Sariputra, Vajjiyaputra and Mahākāśyapa. Considering that each of these are presented, it is perplexing why the Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, is missing in Isibhāsiyāim. Samani Kusuma Pragya attempted to answer this question by using a philological and historical approach to research the identity of Sāiputra/ Sātiputra, and trying to trace the Buddha through him. She notes that the name of the Buddha's mother was Māyā. In Hemacandra's Abhidhānacintāmaṇi 2.151 the synonym of the Buddha is māyāsuta and furthermore saci is one of the synonyms of Māyā. Therefore, it is likely that Saciputra is the name of the Buddha. This is consistent with an ancient tradition where a person and place is given a new name using its synonyms. For example, the town Ratangarh is also known as Vasugarh and Ratnadurga. In conclusion, she claimed, Sāiputta must be the Buddha, but leaves the question open for further research. Because Samani Kusum Pragya was not able to present her paper in person, it was read by Samani Pratibha Pragya on her behalf.

The fourth session, chaired by Marie-Héléne Gorisse (Ghent University and SOAS), began with a presentation by Lucas den Boer (Leiden University) on Jaina and Buddhist Epistemology in Umāsvāti's Time. He argued that the epistemological innovations in the Tattvārthasūtra were partly motivated by encounters with other philosophical movements. Den Boer investigated references to other philosophical movements in the epistemological parts of the text and its auto-commentary. He mentioned that these texts occasionally refer to other schools by name. There are also several implicit references to existing debates and positions that throw some light on the intellectual surroundings of the TS. He argued by explaining some terms which are indicative of other philosophical movements such as padārtha from the Vaiśeṣika school, samyak from the Buddhist tradition and the definition of (a)jñāna from the Yoga school. He mentioned that there is a strong influence of Nyāya thought on chapter one and its auto-commentary.

Jayendra Soni (University of Innsbruck) explored The Digambara Vidyānandin's Discussion with the Buddhist on Svasaṃvedana, Pratyakṣa and Pramāṇa. He presented a comparative study of an epistemological problem debated between the Jainas and Buddhists. Soni discussed Vidyānandin's approach to elaborating the Jaina theory of particulars and universals (aṃśa/aṃśin and avayava/avayavin), to counteract the Buddhist position by quoting Dharmakīrti's Pramāṇa-vārttika. Vidyānandin brings into discussion the concept of perception of an object as a whole, and further continues with svasaṃvedana, pratyakṣa and pramāṇa (selfawareness, perception, and valid means of knowledge). The presentation attempted to deal with these concepts in order to see how Vidyānandin vindicates the Jaina position vis-à-vis the Buddhist one.

The last presentation of this workshop was by Heleen De Jonckheere (University of Ghent) who presented her paper on Two Buddhists, Two Jackals and a Flying Stūpa: Examination of the Buddhists in the Dharmaparīkṣā. This text, written by Amitagati in 1014, is an example of how the Jains dealt with their 'others', especially with Hindus and Buddhists. She focused on the 'strange' story of two young Buddhist laymen who staged climbing a stūpa, which was then lifted up by two animals. Their decision to become monks, after they were saved by hunters who happened to be passing by, does not seem to be based on rational reasons. The tale was clearly meant to be comical. Yet, it is not clear if this laughter was directed towards the Buddhists, or served merely to mock and criticize the Brahmanical Purāṇas and the Brahmanical tradition. De Jonckheere concluded that such stories and satirical criticisms of other religious traditions in the Dharmaparīkṣā were most likely meant to be heard or read by a Jaina lay audience, with the goal problem debated between the Jainas and Buddhists. Soni discussed Vidyānandin's approach to elaborating the Jaina theory of particulars and universals (aṃśa/ aṃśin and avayava/avayavin), to counteract the Buddhist position by quoting Dharmakīrti's Pramāṇa-vārttika. Vidyānandin brings into discussion the concept of perception of an object as a whole, and further continues with svasaṃvedana, pratyakṣa and pramāṇa (selfawareness, perception, and valid means of knowledge). The presentation attempted to deal with these concepts in order to see how Vidyānandin vindicates the Jaina position vis-à-vis the Buddhist one. The last presentation of this workshop was by Heleen De Jonckheere (University of Ghent) who presented her paper on Two Buddhists, Two Jackals and a Flying Stūpa: Examination of the Buddhists in the Dharmaparīkṣā. This text, written by Amitagati in 1014, is an example of how the Jains dealt with their 'others', especially with Hindus and Buddhists. She focused on the 'strange' story of two young Buddhist laymen who staged climbing a stūpa, which was then lifted up by two animals. Their decision to become monks, after they were saved by hunters who happened to be passing by, does not seem to be based on rational reasons. The tale was clearly meant to be comical. Yet, it is not clear if this laughter was directed towards the Buddhists, or served merely to mock and criticize the Brahmanical Purāṇas and the Brahmanical tradition. De Jonckheere concluded that such stories and satirical criticisms of other religious traditions in the Dharmaparīkṣā were most likely meant to be heard or read by a Jaina lay audience, with the goal of directing them back on the Jaina path. They were also sometimes used as a tool for refuting other religious traditions and converting their followers to Jainism.

Dr. Samani Pratibha Pragya

Dr. Samani Pratibha Pragya