The teacher asked the students, “What is the difference between the Ramayana and the Mahabharata?” The students gave answers, each according to his understanding. But the teacher was not satisfied. Thereupon one of the students said. “Sir, you tell us."

The teacher said, “The biggest difference between the two epics relates to rights and obligations. Lord Rama of the Ramayana relinquished his right and his kingdom, and went into exile for 14 years. He could have forgotten for his right if he wanted to. Dashrath did not at all want him to go to the ‘jungle. The people of Ayodhya were filled with anguish at the prospect of his retirement. Had he staked his claim to the throne, excepting Kaikai and Manthra, the whole kingdom would have supported him. But Rama placed his duty above his right. To honour his father’s word was the great aim of his life. Not for a second did he think adversely of Kaikai. On the contrary, he felt obliged to her for having afforded him an opportunity to live in the company of saints for 14 years together. He only dreamed of fulfilling his duty and his conduct reflected his total dedication to his ideal.

On the other hand, the whole plot of the Mahabharata revolves round the battle for one’s rights. The Kauravas and Pandavas were cousin-brothers out the odour of brotherly affection, the sweetness thereof and the feeling of oneness are all conspicuous there by their absence. We meet with hypocrisyand fraud with the sole objective of defeating the pandavas. And the Pandavas lost their all; they lost their kingdom, their queen. They accepted 12 years of exile in the forest; the last year they spent in perfect anonymity they fulfilled all the conditions laid upon them, but when they returned to claim their kingdom, the Kauravas refused to yield “even an inch of ground” Lord Krishna persistently argued with the Kauravas, “ If nothing ‘more, at least give the Pandavas five villages to live in “There upon, Daryodhana said, “You talk of five villages, but I’m determined not to yield them any ground whatsoever—not even that equivalent to an eyeless needle;"

Here are two examples before us. The first highlights intimate relationships marked by cordiality. Such cordiality saves man from becoming self-centred. He thinks more in terms of the family, society and the country, than himself. He moves in a direction well thought and reasoned out. He has absolutely no axe to grind. He rises above considerations of self-comfort, prestige or power. Only he who holds his duty as the supreme aim of his life can do so.

That civilisation may be said to be thriving which gives birth to dutiful individuals, that century may be said to be successful which guarantees a constant flow of the current of dutifulness so as to be within the reach of all; that tradition may be said to be flourishing which imparts dutifulness to people, Where the transparent glory of dutifulness spreads all round, the whole atmosphere stands trans-formed. The need of the hours is that, putting aside all meaningless preoccupations with position prestige and comfort, the individual should give himself wholly to his duty. This applies, not only to the family and society, but also to the religious, social and political organisations. Can a man who is blindly involved in the mad race for position and power and self-gratification, be expected to preserve the high domain of duty?

Millions of people see, hear or read the Ramayana and the Mahabharata in the form of an epic play, poem or book; It is surprising that as compared to the eagerness displayed by people for witnessing or hearing these epic tales, not even the hundredth, nay, not even the thousandth part of such ardour IS manifested in assimilating these in one’s everyday living. The ideal character of dutiful Rama should be an inspiration to everyone, the current T.\/. Serial on the Ramayana has proved to be a hit. People readily give up everything—work at office, shop or home, religious meetings and discourses—and flock to witness the Ramayana. As the noble character of Rama unfolds, people are never tired of praising it. But seriously, who cares to follow in Rama’s footsteps? Where is to be found any serious effort to live the character of Rama in one’s life, or to transcend the character of Daryodhana? Who cares to rise above the illusion of power-and self-interest, to objectively appraise one’s own conduct?

Prompted by power and craving, the individual seeks new ways to fulfil himself. But in the name of dutifulness, he even closes the ways that are open. This spectacle of man’s infatuation with himself reminds me of a couplet of mine:

You know and comprehend everything But action, which is beyond your ken!

The man who is unconscious, may be brought to consciousness again, and something maybe done to awaken a man who is asleep. But the man who deliberately ignores the path of duty-what can anyone do for him? The great need of the times is that the individual should change his approach and prefer his duty over his rights.

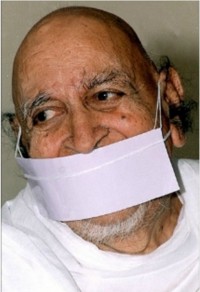

Acharya Tulsi

Acharya Tulsi