| | The Times Of India, May 15, 1997 Jainism & Relativity

The Jaina perspectives of syadavada hold that a proposition is true only conditionally and not absolutely. This is because it depends on the particular standpoint, naya, from which it is being made; that logically a thing can be perceived from at least seven different standpoints, saptabhangi-naya; which leads us to the awareness of the many-sidedness of reality, or truth, anekanta-vada. |

Realist Ethics

At no time were these limited to epistemological questions, of concern only to the philosophers. Since human relationships, personal or social, are determined by our perceptions of ourselves and of others, which we mostly assume also to be true absolutely, giving rise to conflicts and violence because the others believe the same about their judgments, the very first step towards living creatively is to acknowledge the relativistic nature of our judgments, and hence their limits. While being a distinct contribution to the development of Indian logic, the Jaina syada-vada has been, most of all, a realist ethics of not-violence, ahimsa. The two are inter-related intimately.

An article, “Syada-vada, Relativity and Complementarity” by Prof. Partha Ghose, a theoretical physicist says, that P. C. Mahalanobis was the first to point out, in 1954, that "the Jaina Syada-vada provided the right logical framework for modern statistical theory in a qualitative form, a framework missing in classical western logic."

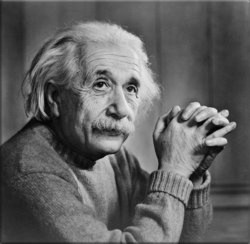

J B S Haldane saw a wider relevance of syada-vada to modern science. And Prof. Ghose speaks of the "most striking" similarity of syada-vada to Niels Bohr's Principle of Complementarity, first noticed by D C Kothari. Furthermore, he says: "The logic of Einstein's Special Theory Of Relativity is also very similar to syada-vada."In Einstein's relativity theory, Prof. Ghose points out, "the conventional attributes of mass, length, energy and time lose their absolute significance"; whereas in Bohr's complementarity theory, "the conventional attributes of waves and particles lose their absolute significance."

As in syadavada, what that means is, that the physical value of the former is only relative to the theoretical framework in which they are being viewed, and to the position from which they are being viewed. None of them is a fixed, absolute truth about the physical universe, as was assumed in the Newtonian physics. It would soon be discovered, too, that they are relative also to the observer who observed them.The Upanishad and the Jaina syada-vada had argued that reality carries within itself also opposites as its inherent attributes; and, therefore, no absolute statements can be made about it. But no sooner was this said than it was shown itself to be subject to the same limitation.

In the wake of the relativity theory, which had already shattered the classical notions of physical order, de Broglie, a French prince, demonstrated, in 1924, that an electron is both a particle and a wave, whereas quantum mechanics had held the particle-wave duality. This discovery was even more upsetting, but experimentally proved.

The most upsetting was the subsequent proof, provided by Werner Heisenberg in 1927, that no events, not even atomic events, can be described with any certainty; whereas the natural sciences were rooted until then, and are so even now, in the mistaken notion that scientific rationality and its method gave us exact and certain knowledge of the universe. Heisenberg called it the 'Principle of Uncertainty'. Its substance was not only that human knowledge is limited but also that it is uncertain. That is to say, there are aspects of reality about which nothing definite can be said - the avyaktam, or the 'indeterminate', of the Jaina syada-vada.

Subsequent Proof

In his book "The Dancing Wu Li Masters: An Overview of the New Physics”, published in 1979, Gary Zukav said: "The wave-particle duality marked the end of the 'either-or' way of looking at the world. Physicists no longer could accept the preposition that light is either a particle or a wave because they had "proved" to themselves that it was both, depending on how they looked at it."

Syada-vada, and with it anekanta-vada, had held that there are several different ways of perceiving reality, each valid in its place, and none of them true absolutely. But how do we judge the validity of our perceptions, by what criteria, by what method?

These are the main questions of epistemology. Since modern science has been a method of perceiving reality, even if only physical reality, it is epistemology with a certain method.Einstein had placed great emphasis upon that fact; and he was one scientist of modern times who had placed also the greatest emphasis upon the question of method in theoretical physics. His writings in that regard are to be found in his Ideas and Opinions, published in 1954. He said: "Epistemology without contact with science becomes an empty scheme. Science without epistemology is - insofar as it is thinkable at all - primitive and muddled."

Limits of Logic

Concerning the method, as physics advanced, it became clear that the theoretical element in scientific laws cannot be abstracted from empirical data, nor can it be of pure logical induction. There is no bridge between the two of a kind that one necessarily implied the other. According to Einstein, the "axiomatic basis of theoretical physics cannot be abstracted from experience but must be freely invented"; "experience may suggest the appropriate mathematical concepts, but they most certainly cannot be deduced from it." Neither can pure logic give us knowledge of the physical world. On this point also, Einstein was unambiguous. "Pure logical thinking cannot yield us any knowledge of the empirical world", he says; "all knowledge of reality starts from experience and ends in it. Propositions arrived at by purely logical means are completely empty as regards reality." The passage from sense impressions to scientific theory, Einstein says, is through "intuition and sympathetic understanding."

In brief, the two revolutions of relativity theory and quantum mechanics and what followed, had rendered naive realism, pure empiricism, pure logical thinking, and materialism, when each claimed to be the only way to knowledge and its certainty, to be incompatible with scientific method. What had hitherto been assumed to be the scientific method and, therefore, also the only true rationality, and was sought to be imposed upon the rest of the world was, in its absoluteness, discarded.

And in all those movements of the New Physics, the Jaina syada-vada and anekanta-vada are clearly manifest.

Wikipedia:

Chaturvedi Badrinath

Chaturvedi Badrinath