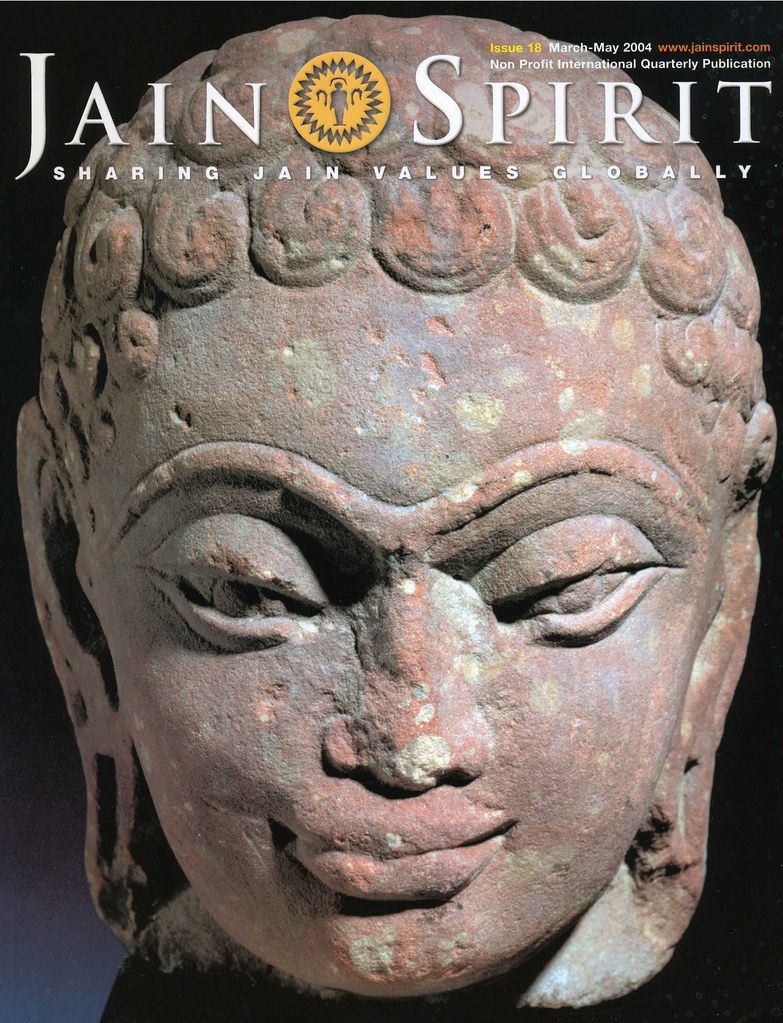

Jain Spirit magazine - A non-profit International Quarterly Publication - #18 (2004-2). Photo - Bridgeman Art Library: Jain Head, 6th century AD, Mathura region, India.

Jain Spirit magazine - A non-profit International Quarterly Publication - #18 (2004-2). Photo - Bridgeman Art Library: Jain Head, 6th century AD, Mathura region, India.Understanding Aparigraha

Understanding Aparigraha. - Robert Zydenbos Examines The Meaning Behind Non-Possession

Understanding Aparigraha. - Robert Zydenbos Examines The Meaning Behind Non-Possession From earliest times, Jainism has been characterised as a way of life in which wafers or 'vows' play a very prominent role. One characteristic of a vrata is that it is an individual matter. Certainly the vows have a very strong social relevance, but it is up to the individual to decide which vows he or she wishes to adopt and to what extent. The vows help to improve the quality of life here and now, but they are also a means of influencing one's condition in the afterlife by influencing the accumulation of karma. Very prominent in Jain thought are the five main vows: ahimsa, satya, asteya, brahmacharya and aparigraha - not to harm other living beings, to speak the truth, not to steal, to be chaste and not to acquire possessions exorbitantly.

Jains have traditionally given most prominence to the first of these five vows, ahimsa, to such an extent that Jainism is often referred to as 'the religion of nonviolence'. The reasons are understandable. Violence as a rule involves physical or vocal acting in the world, and its results are usually immediately visible: injury, death or expressions of suffering in the people or other living beings who are the victims of the violence. The world around us immediately impresses upon us some of the results of our actions. This is not always the case when one does not live and act in accordance with the other four major Jain vows.

Much of Jain literature, both the popular and the more scholarly, depict ahimsa as a kind of master-vow from which the others can be derived. Indeed, it is possible to see falsehood, theft, unchasteness as involving violence to some degree. But does it need to be so in the case of the accumulation of possessions? Surely not. It is remarkable that the Tattvarthasutra, the foremost Jain philosophical text, does not give ahimsa any special importance in comparison with the other vows. All five are treated as equally significant, and the reason for this becomes clear when one considers how our acts affect the quality of our present lives as well as of the lives to come. The Tattvarthasutra discusses the path to liberation through right belief, knowledge and conduct in terms of karma. If our understanding of the world is faulty, it is because of one particular type of karma, the knowledge-obscuring karma (jnanavaraniya); if our basic beliefs about ourselves and about our place in the world are faulty, it is due to deluding karma (mohaniya). It is interesting to look at the vrata of aparigraha from the point of view of karma, the choice to place a limit on what one possesses (differing according to whether one is a layperson or a monk or nun, as with the other four vows).

The word parigraha has been variously translated into English: 'accumulation of possessions', 'attachment', 'passion for possessions'. Aparigraha has been translated as 'non-possession' and 'possessionlessness'. These translations of aparigraha are clearly exaggerated, since in practice all people possess something; even a Digambara muni has at his disposal at least his piccha and kamandalu. Only the enlightened soul that has left its last earthly existence and attained final liberation is entirely without possessions. Etymologically, parigraha can be understood as 'grabbing around' (the Sanskrit verb grah is related to the English grab), which is quite meaningful in the definition in Chapter 7 of the Tattvarthasutra which is, sutra-like, very brief: murchha parigraha. Murchha means 'infatuation, delusion, hallucination'. In the commentary Sarvarthasiddhi by Devanandi Pujyapada, written in the fifth century, we read: "Also in the absence of an external object, he who thinks 'this is mine' indulges in parigraha. (Asaty api bahye mamedam it's sankalpavan saparigraha eva bhavat.) This clearly shows that neither the object that is desired, nor the question whether that object is obtained or not, determines whether one indulges in parigraha or not: it is a matter of inner attitude.

Is it infatuation to possess anything at all? No. As Pujyapada points out, one should read the sutra murchha parigraha in context. The explanations of the non-observance of the five major vratas begin earlier in the text, where it is said that himsa is injury committed out of passion (pramattaprayogat) and the same should implicitly be understood here as well, hence "it is established that there is no delusion and no parigraha in one who is not moved by passion and who possesses [right] knowledge, faith and conduct," (jnanadarsanacaritravato 'pramattasya mohabhavanna murchhastiti nishparigrahatvam siddham); "furthermore, there is no parigraha of that knowledge etc. because they are the nature of the self," (kim co tesham jnanadinam... atmasvabhavatvad aparigrahatvam). To possess something is in itself not bad; what matters is our attitude towards that which we possess, and whether this attitude leads us astray from the correct understanding of what we are, namely: non-material consciousness. "And passion etc. are to be rejected, because they arise from karma and are not of the nature of the self... All faults originate there." (Ragadayah punah karmodayatantra iti anatmasvabhavatvaddheyah... Tanmulah sarve doshah.)

Chapter nine of the Tattvarthasutra says just how seriously we should take our attitudes and thoughts on such matters. This chapter discusses the ways in which we control the accumulation of new karma. One of these ways is meditation or concentration (dhyana), which is of four types: two of them lead to liberation and two others lead to the accumulation of bad karma. One of the latter variety is fierce concentration (raudraj namely on four topics, as Pujyapada mentions: violence, falsehood, theft and the protection of possessions (himsa-'nrta-steya-vishayasamrakshana). It is the feeling of attachment to something that is detrimental, not possessing in itself, since certain possessions help us avoid sufferings that in turn could create anger in us and along with that bind more bad karma. Moreover, it is only when we already possess something that we can part with it, which is the significance of charity. "Parting with that which is one's own for the sake of benefitting is charity," (Anugrahartham svasyatisargo danam) says the Tattvarthasutra. As Pujyapada writes: "Benefitting oneself as well as another one gathers good karma and helps another develop." (Svaparopakara 'nugrahah. Svopakarah punyasancayah paropakarah samyagjnanadivrddhihj.)

The avoidance of parigraha is not the same as suffering poverty. Religious life is a path towards the complete eradication of suffering, and certain possessions help us on that path: those through which we learn more about ourselves or that keep us healthy. The suffering of poverty does not necessarily help us grow more mature and such suffering, in a metaphysical sense, may make us feel dependent on what we are not, and distort our understanding of what we are. What ultimately matters is that we realise that we are souls, consciousness, not to be identified with the material objects around us, and that we should neither be distressed by limited possessions nor let our estimation of our own worth depend too much on what we possess, as the monks and nuns of the tradition demonstrate it to a very high degree. The vow of aparigraha is highly meaningful: certainly just as meaningful as any other of the four main vows.

Prof. Dr. Robert J. Zydenbos is professor of Indology at the University of Munich, Germany, where among other subjects he teaches Indian philosophy and religions.

Prof. Dr. Robert J. Zydenbos

Prof. Dr. Robert J. Zydenbos