For more than two millennia Jains have integrated female divinities into their religious practice as protectresses and emblems of their ancient tradition to such an extent that anybody only slightly familiar with Jainism's art or architecture would still be aware of their ubiquitous presence in the devotional life of renunciants and laypeople, whether Svetāmbara or Digambara. Regrettably the first western scholars of Jainism, whose familiarity with Jainism was largely derived from texts, either ignored this vital component of the religion or attributed it exclusively to borrowing and processes of Hinduisation, which supposedly became more pronounced through the medieval period. This misapprehension was decisively corrected by John Cort whose significant paper 'Medieval Jaina Goddess Traditions' (Numen vol. 34 1987) makes clear how the personalities of the goddesses found within Jainism, while often overlapping in some respects with their Hindu counterparts, are distinctively Jain in their benevolence and vegetarianism, reflecting the transformative influence of an ethic of non-violence.

However, despite this timely reminder, it must be admitted that few studies of individual Jain goddesses have yet been undertaken and those interested in this aspect of Jainism have generally been compelled to research laboriously in disparate and often obscure art historical publications or to sift through large numbers of hymns in Sanskrit, Prakrit, Gujarati, Kannada and other languages. We must therefore congratulate Professor Nagarajaiah who in a relatively short span has assembled here a cornucopia of apposite texts and choice illustrations relating to Sarasvati, perhaps the most attractive of Jainism's many goddesses, and described with impressive learning the origin and dissemination of her iconography and worship.

Sarasvati is of course a pan-Indian deity who was worshipped by Hindus, Buddhist and Jains. Originally a riverine goddess, she is representative of the sacral association of water and womanhood which has always played a significant part in informing basic Indian perspectives on female divinity. Jainism is not preoccupied with Sarasvatī's identity with the river of the same name, but rather from near the very beginning of its artistic tradition has highlighted her role as goddess of culture and wisdom and also protectress of the scriptures. A myriad reproductions in painting and sculpture of Sarasvatī, typically depicted holding book or vīnā and seated on a lotus or a swan, testify to her longstanding hold on the Jain imagination. Professor Nagarajaiah's homage to her in this elegant little volume will fascinate and delight scholars and general readers alike.

03.03.09

Paul Dundas

Reader in Sanskrit University of Edinburgh Scotland, U.K.

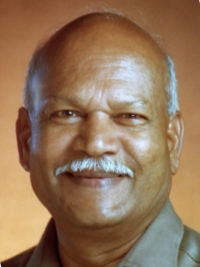

Prof. Dr. Nagarajaiah Hampana

Prof. Dr. Nagarajaiah Hampana