The following article by the German scholar of Jainology Prof. Walther Schubring (Hamburg University) was published in a very rare special issue of The Voice of Ahinsa, the monthly magazine of the World Jain Mission at Aliganj, U.P. (The Voice of Ahinsa - Lord Mahavira Special Number, Vol. VI, No. 3-4 (Mar.-Apr. 1956) - pp. 67-68).

A Saying of Mahavira

In 1942 I published the transcribed of the Ṛṣabhāṣitasūtra (in Prakrit: Isibhāsiyaim) which in a rather primitive way had been printed at Indore in 1927. This edition, provided with a critical introduction, in 1951 was followed by a Sanskrit Chhāyā from my own pen with a view to interpret the highly interesting and doubtless old work in which many crucial passages are in the way of an easy understanding.

The Ṛṣabhāṣitasūtra consists of 45 chapters, nearly all of which follow the same plan, viz., a laconic, and often dark, saying, to which are added explanatory and other verses. The conclusion is a stereotype phrase. Each of those sayings is attributed to an Arhat and Ṛṣi who, as some quotations in literature prove, is considered as a Pratyekabuddha. One is rather stupefied among them to find Lord Pārśva and Lord Mahāvīra.

For everyone knows that a Pratyekabuddha, inspite of his having won perfect knowledge, is far from handing it over to disciples, but keeps it with himself, thus being in plain contrast to both those Overmen and all other Tīrthaṅkaras.

What has induced the unknown author to smuggle in both those into the host of Pratyekabuddhas, we shall perhaps never know. Let us, with due respect, read what He, to whom this number of the Voice of Ahinsa is dedicated, according to the anonymous author says in the beginning of

Chapter 29.

In all quarters floods are flowing. Is there no checking of the flood? [Thus] questioned a wise man should tell. How can the influx of the flood be checked? (1)

This [is] a saying of the Arhat and Ṛṣi Vardhamāna:

Five are sleeping with him who is awake, five are awake with him who is sleeping. Through five [which are awake] he attracts passion, through five [which are sleeping] he parts with passion (2).

When sound, form, smell, taste, and touch are reaching his ear, eye, nose, tongue, and skin, he must not delight in an agreeable impression, nor decline owing to the bad ones. If a man does not rejoice at an agreeable thing, nor is angry at the contrary, and is on his guard in neutral cases, then the flood is checked (3-12).

The five senses, when not subdued, lead men to Saṃsāra, but, when duly restrained, to Nirvāṇa (3).

By unrestrained senses the soul is carried forth upon a bad road, as is a driver on the big road by his unrestrained horses (14).

When his senses are well subdued, he does not follow the [sensual] path, as a careful driver with his obedient horses [follows the right road] (15).

He must conquer his mind and then turn his back to the world of senses, like a warrior sitting on his obedient elephant (read: vidheyaṃ gayaṃ) ready to fight [turns his back to all that is dear to him] (16).

He who, having conquered his mind and his passions carefully practises austerities, being a pure soul, shines forth like the sacrificial fire, when fed with grains (17).

Even the gods pay respect to him who delights in righteousness, is persevering (or: wise, dhīra), has subjugated anger and subdued his senses and whose only concern is

Moksha (18).

A man who is totally free from passions, has self-command, is guarded by all [moral] guards, whom all pain has left, - he has attained the goal.

Thus [a man who] has attained the goal, has resigned, is free from sin, has self-command, is able, fit, perfect - [he] shall not be born again. Thus I say.

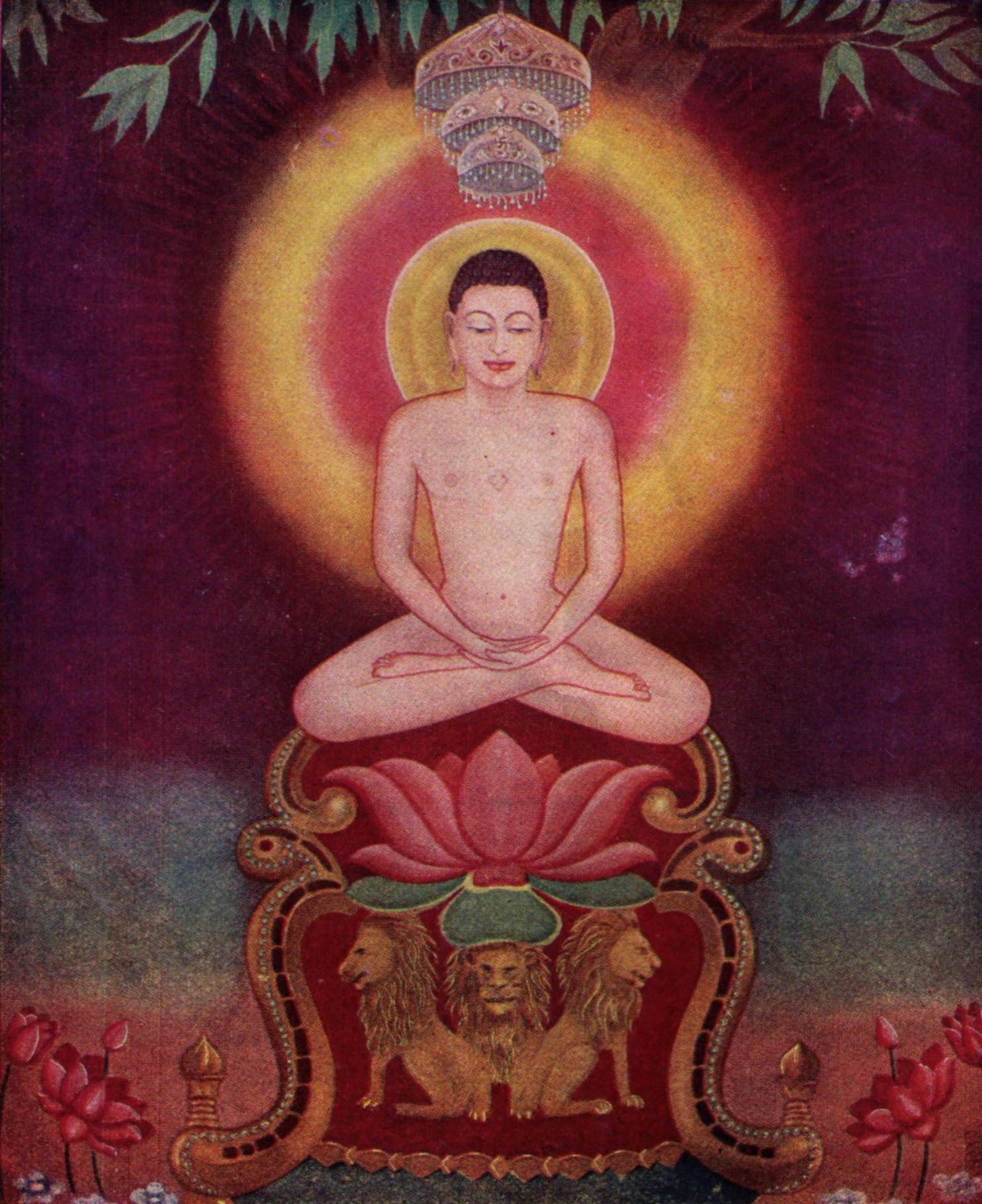

Tīrthaṅkara Vardhamāna Mahāvīra, an apostle of Ahinsā (Frontispiece of the op. cit. issue of The Voice of Ahinsa).

The Vardhamāna Chapter

As to this name, it is well known that there has lived more than one devoted Jain author Vardhamāna. But the fact that the next but one chapter 31 is ascribed to the Arhat and Ṛṣi Pārśva makes it clear that in chapter 29 the 24th Tīrthaṅkara is meant.

That chapter is too long for being reproduced and discussed here. This much, however, may be said, that apart from the words caujjame niyanthe, a monk with (only) four vows, it contains nothing that could be called characteristical for Mahāvīra's great predecessor. Just the same is the case with the saying attributed to the latter.

We all of us know his style, as tradition has handed it down to us, as being precise, clear, and distinct prose. Questions like those in the above verse are far from his manner to give expression to his thoughts. Moreover, it was not his custom to refer to "a wise man" other than he himself.

After all, we are justified to consider our verse as apocryphal, just as that whole collection of the aphorisms of pretended Pratyekabuddhas, called Ṛṣabhāṣitasūtra, cannot well claim to be more than a characteristical by-product of Jain creed.

Walther Schubring

Walther Schubring