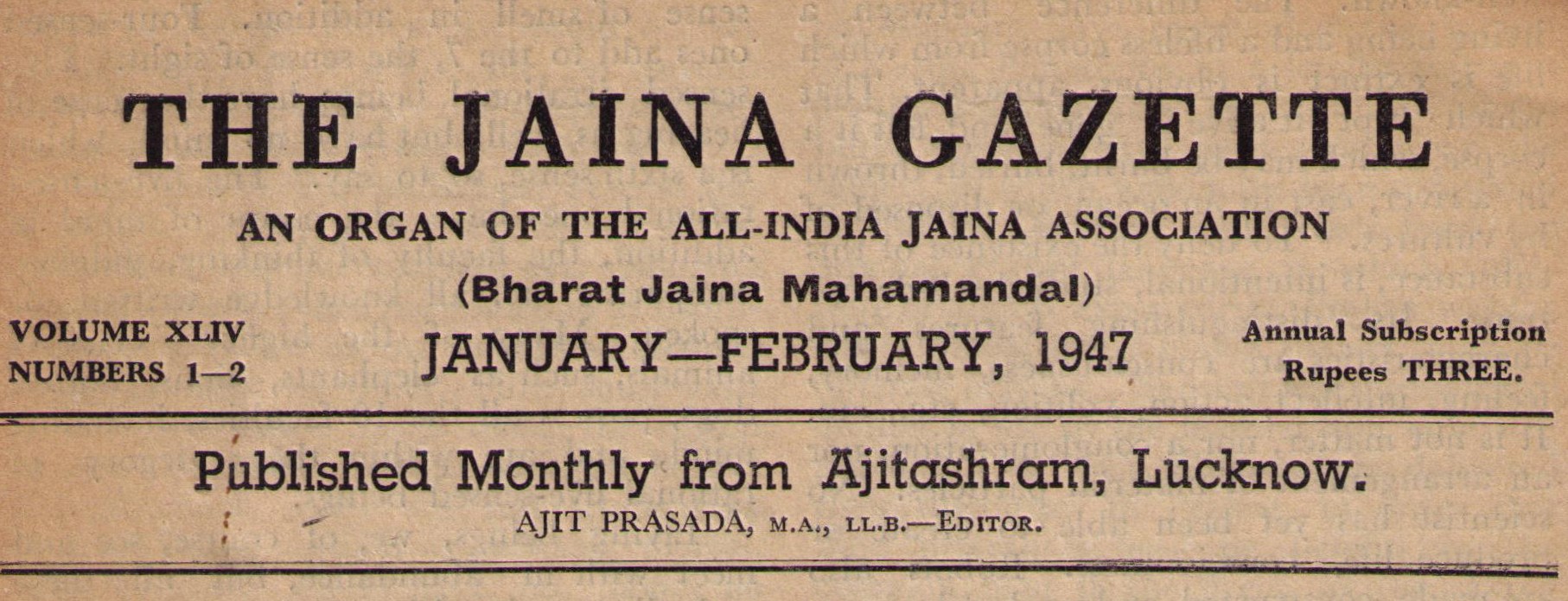

The paper was first published in January-February, 1947 in The Jaina Gazette, Vol. XLIV (No. 1-2), pp. 18-20.

Flexibility, Liberty and Equality of Jainism

This was written in September 1906 by the late Mr. J. L. Jaini as an Introduction to the book "Life of Mahavira" by the late Mr. Manik Chand Jaini Advocate of Khandwa, published in 1908 [Editor of The Jaina Gazette].

Mahavira was one of the greatest men of his, or of any other age. The enormous influence that his very name still exercises upon a considerable portion of humanity puts this fact beyond the least doubt. With Buddha, his great contemporary, with Christ and Mahomet that flourished centuries after him in Syria and Arabia, and many other great religious reformers of the world, he holds a sure niche in the gallery of the Great Immortals. My present purpose is neither to establish his greatness - a superfluous task, nor to descant upon the details of his noble theological and other doctrines - to do which is out of place; but to briefly indicate the way in which the present may practically take a leaf out of the book of the past, and we, by imitating the principles (not the details many of which we do not know) of Mahavira's life, 'may make our lives sublime.' The eternal sun of his great example is shining over all of us; and how much we benefit by it obviously depends upon our individual mental, moral and spiritual evolution and necessities. The light and glory of this hero is enveloping the Earth and how we partake of its bliss will entirely depend upon how the souls of each one of us sends.

"A sweet and potent voice, of its own birth,

Of all sweet sounds the life and element."

One great lesson of Jainism should never be forgotten, that we are what we have made us and that our future is to be made by us now. This cardinal doctrine of self-help involves the perception of the great responsibility of life. Life is a serious affair; and although its visible duration in time is but three or four scores of years, its continuity before birth and after death makes it a grand, though a mystic and puzzling, affair. The doctrines of Mahavira help us in the solution of this pre-natal and post mortem mystery; and his life shows us the line of success in the present. We are concerned here only with the last.

The first principle that underran the life of Mahavira seems to have been his irrepressible desire to know the cause of things, of all things. By study, observation, steady thinking and tapas, which in the India of those days was an essential part of the life of a true scholar, - his inquiries led him to an entire satisfaction of his desire. He attained Nirvana. The pursuit of knowledge is a very lonely road, and doubts and dejections of various kinds beset it at every step. But the brave heart and keen eye of our last Lord overcame all, and he reached the eternal fields of light and learning. All the meaningless superstitions and customs, to which the Jainas bow in the unwonted company of other sections of the Indian people, would fade away in a generation's time, if even fifty per cent, of the professed Jainas were to understand their true relation to the outward world and the purpose of their brief sojourn in it. Indeed it has struck me at times as a futile though fascinating speculation, how Lord Mahavira would have lived his life in this age, in accordance with his own teaching of respect for place, time and occasion. Anyhow the lesson is clear. Steady pursuit of knowledge through books and personal observation and meditation (which does not mean a verbal chanting of Siddhaji, Siddhaji while the eyes are gazing into vacancy, and the mind is busily scheming the next investment of your thousands in Bombay cotton or Calcutta silver).

Another point is Lord Mahavira's broad-mindedness. That he started a movement which embraced persons of all castes and creeds and of all degrees of civilization in that hoary past, very amply attests the breadth of view, with which he conceived Jainism. Jainism was never meant to be the narrow or exclusive thing that it appears to have become now. Kings, warriors, Queens, Brahmanas, Sudras, the aborigines (who most probably are symbolised by the beasts and birds that attended the Samavasaran of Lord Mahavira) all profited by his teachings. Like Buddhism in its first centuries, it also took up the cause of the masses who were being demoralised and tyrannised by the exclusive, privileged and influential priestly classes. But it is curious that Jainism itself has become priest-ridden and ignorance-flooded in the immediate past. An interminable mass of rites and ceremonies has replaced its pristine simplicity, and minor details of eating before sunset and drinking strained water and conducting big rath-yatra processions, and fighting big communal cases gave all, but made people forget that behind these comparatively unimportant details there lies a wealth of principles of cosmopolitan application. To defend the above practices by saying that these things are good for the masses, is to assume these latter to be far, far behind their times and unable to understand the right road to their salvation. More liberalism of a true stamp, namely, that liberalism which will insist upon the great and fruitful principles of Jainism, as distinguished from its minor practices, is badly needed by our community and if a study of the life of Mahavira does not inspire us with it, my idea is, the fault is in us.

A third lesson that this life teaches us is a readiness for change. A conservative spirit is more prevalent all over the world than it seems. Our actions change sooner than our ideas. This is why we still in name adore the teachings of our Tirthankaras, while in fact we all know how far our actions run from these teachings. But the Jainas, along with other Indians, seem to have forgotten that too rigid conservatism is a sign of decay and ultimate ruin,and that change is an essential condition of progress. My chief hope for the Jaina cause is that I observe even the most staunch opposers of English education and those who have received it, are themselves obviously succumbing to its siren charms. But my regret is only this. We are moving too slowly; and because we have, in theory, determined not to change, we are walking with large logs of prejudices that we put before us at every step. It is rather a curious method of walking. The work of reform is doubled in difficulty. Before we can take our friends another step with us, the log that they have put before them has to be removed first. Whatever our merits, the readiness to see stern facts in the face is not the most marked of them. The times demand purity and strength in social and religious affairs, but not along ascetic lines. Our asceticism is to be of a different type. We are not to leave temptations and distractions behind us to prey upon our weaker brethren and sisters in the towns, we have to stay and fight and destroy, at least weaken these foes of humanity. This involves contact with hundreds of people not of our way of thinking and feeling, and we must, therefore, be prepared to have not a few of our angularities, that we may be apt to consider to be distinctive marks of Jainism, rubbed off in our work of social and religious reform.

A fourth point, which perhaps could be given the first place, is the great freedom that Mahavira gave to women. In theory Jainism never denied equality of spiritual rights to women. In practice they have been put down lower than men, as a matter of course. But what is more important is that they have been given very few, if any, chances of cultivating their minds and bodies. It is one of the most scandalous features of our community and cannot be remedied too soon. Movements for dispelling the ignorance of our ladies are already afoot in the north and south of India, and the duty of the true followers of our last Lord is to make these movements a glorious success. We should not fear that education and knowledge of rights will make our women disobedient or 'unsexed' or immoral. These fallacies have been exploded over and over again, and I shall only add that we must look to the very great gain that we will have by the excellent early training that educated mothers will give to Jain children and to the more cultured and enjoyable home life than is found in Jaina families now.

A fifth point should appeal to those of the younger spirits who wish to rise higher and higher, so that the crown of fame may rest on their heads. To such the life of our last Leader teaches the great lesson of a devoted pursuit of one central ideal of life. I do not know if there is a more painful or sinful life than a purposeless existence. Hundreds of our young men have noble aspirations but their ambitions are "thick-sighted". This blindness to a central purpose of life causes many a noble wreck; and an honest attempt must be made to remove it. But in many cases the object of life can be seen with a little exertion, and there the beholder must know that having seen he is to follow Our Lord Mahavira saw the light and followed it to Nirvana. That, as the Shastras say, cannot be attained now, unless we are born in the Videhas, but still by pursuing one great ideal we may be nearer the goal, and who knows but that a strenuous and industrious life in pursuit of Truth, may yet lead a fortunate soul to that land of bliss, where the Kevalins still flourish and where man can still attain eternal freedom from Karmas?

In the end I must say that it is impossible to draw all, even the most important lessons from Lord Mahavira's life. It is all golden; and its richness is inexhaustible. To my mind the five points given above seem to be of special application to the present needs of the community and I have given them. For the rest I must again say that it is a question of individual tastes and capacity of mind and soul. There is our Lord's plenty and let everyone take away as much of it as he can or desires to.

J. L. Jaini

J. L. Jaini