This essay was published in the Journal of the Oriental Institute (Baroda), JOI 22, 1973, pp. 455-463. To make this online reissue citeable, the page numbers are added to the text (see squared brackets).

Nikṣepa - A Jaina Contribution to Scholastic Methodology

[455] The beginnings of brahmanical learning and science sprang from the needs of the interpretation and correct tradition of the Veda; Jaina monastic scholarship originated and developed from the comparable task of explaining and handing down to pupils the sacred scriptures of Jainism. The extraordinary thoroughness with which the Jaina ācāryas tackled this, to them, all-important task, combined with their remarkable ingenuity, would seem to have been responsible for a distinctive trait of Jaina scholasticism: the special emphasis on methodology. Theoretical disquisitions on methods for interpreting and explaining the sacred texts play a considerable role in early exegetical literature; quite a number of different systems, of interpretation tools, were evolved, and it might be said that most of the original Jaina contributions to Indian scholarship were made in the field of methodology.

Philosophically most interesting and relatively well-known is the “relativity theory”, the syādvāda; there is besides the related, but different and independent system of the nayas, the seven possible modes of approach and description, one of which is singled out without regard to the others according to the need and purpose of the case; the general method of approaching a subject is further systematized in the form of the four anuyogadvāras which supply the title of one of the canonical books; and, leaving aside some minor artifices such as the combinations of the tribhaṅga and caturbhaṅga, there is the subject of the present article, the nikṣepa. This curious system of subjecting key words to an investigation by applying a scheme of fixed viewpoints may be less fruitful philosophically, but it occupies almost a key position in early scholastic literature, particularly the nijjuttis. It is of prime importance for the understanding of these difficult and hitherto rather imperfectly explored texts which, with their old commentaries, the cūrṇis, represent the earliest post-canonical development of Jaina doctrine and exegesis. Yet I have not yet seen a full description which would explain the details of the nikṣepa technique and make clear its general significance, and practical use. This is why it is hoped that the following exposition will not be deemed superfluous.

As a synonym of nikṣepa, the commentators sometimes use the word nyāsa, which can not only mean the “putting down” but also the “bringing forward”, the broaching of a subject; so it may be conjectured that the original meaning of nikṣepa is the putting down of something, or the writing down of a word, in order to subject it to a systematic consideration. In what may be called the [455|456] original form, the prototype of the nikṣepa as found in the nijjuttis and allied literature, this process is performed under the four aspects of nāma, sthāpanā, dravya and bhāva. Nāma is the designation; what is considered first of the nikṣepa object is its purely linguistic side, the designation as such. Sthāpanā is the pictorial or material representation of the animate or inanimate, concrete or abstract nikṣepa object, its effigy or illustration. Dravya denotes the substantial, material, concrete, non-mental aspect, bhāva the mental, psychical, spiritual, religious one. This original fourfold nikṣepa - its various amplifications will occupy us later - is applied first to the title of the canonical work to be explained; if this title is a compound, to each of its members; subsequently to the titles of each chapter and subsection, lastly perhaps to a few key words of the sūtra text. I quote as an example the beginning of the Uttarādhyayana exegesis, using this term for the nijjutti plus its cūrṇi and/or ṭīkā, which inseparably belong to it and without which the nijjutti is not intelligible.

The pupil first asks the teacher, in most characteristic archaic circumstantiality, whether the text is an aṅga, sing., or aṅgas, pl., whether śrutaskandha sing., or pl.; adhyayana sing. or pl.; uddeśaka sing. or pl.; the teacher's answer, no less laborious: aṅga sing. no, pl. no; śrutaskandha sing. yes, pl. no; adhyayana sing. no, pl. yes; uddeśaka sing. no, pl. no; which simply comes to: one śrutaskandha divided into a plurality of adhyayanas without further subdivision.

The result that we have to do with one Uttarādhyayana - śrutaskandha means that we now have to “nikṣepize” - begging pardon for the word-monster; the texts simply use the verb ni-kṣip - first, uttara; second, adhyayana; third, śrutaskandha. Further, the first adhyayana is entitled vinayaśruta. Vinaya is nikṣepized in the Dasaveyāliya-nijjutti, and as in the fixed traditional order of the ten nijjuttis this work precedes the Uttarādhyayana-nijjutti, the reader or listener can be referred to the treatment of vinaya in the Dasaveyāliya exegesis. There remains to be nikṣepized the word śruta. The first stanza of the vinaya-śruta adhyayana begins with the words saṃjogā-vippamukkassa, “of him who has become free from all worldly ties”, and this leads up to the nikṣepa of saṃyoga. This nikṣepa occupies no less than 32 nijjutti stanzas, for it comprises the diverse and intricate doctrines of the combination (saṃyoga) of atoms to aggregates, of the interpenetration (saṃyoga) of the pradeśas of the five astikāyas, of the contact (saṃyoga) of indriyas, manas and sense-objects, the combination of sounds to words, of singulars to duals and plurals etc.

All this does not, of course, contribute anything to the explanation of the Uttarādhyayana stanza, it has nothing whatever to do with it and thus is a good example of what is so bewildering and irritating at the first acquaintance with the nikṣepa: the text passage or title to be explained, the context of the word which has given rise to the nikṣepa is very soon completely lost sight of, so that e.g. in the nikṣepa of the word sūtra (occurring in the title of the second aṅga, the [456|457] Sūtrakṛtāṅga) we suddenly find ourselves in a treatise on the different threads (sūtra) of textiles. In the case of saṃyoga - of special interest because this is a well-known nyāya term raising the problem of possible nyāya influence - the nikṣepa has become a technical device for dragging in a number of difficult chapters of Jaina doctrine which have nothing to do with the text to be explained but the inclusion of which in the teaching programme seemed necessary or desirable if only to make the instruction richer and more rewarding for teacher and pupil. In the aṅga title just mentioned, Sūtrakṛtāṅga, there occurs the word kṛt or kṛta derived from the root kṛ; and from this slender hook is suspended a treatment of another derivation of kṛ, the word karaṇa with its particularly multifarious meanings, a treatment filling a dozen or more printed pages of the commentary. Moreover, this karaṇa-nikṣepa recurs in two other nijjuttis; which means that in two cases out of three the possibility of referring to the first occurrence was not made use of - for the reason just mentioned: the desire to include this matter in the exegesis of the sūtra in question, to enrich the respective teaching programme. This corresponds exactly to the well-known fact that one and the same illustrative story or dṛṣṭānta may be used by and recur in the exegetic tradition of several canonical texts.

Cases like those of saṃyoga and karaṇa may appear to us as a rank growth of the nikṣepa, a misguided development. But it should not be overlooked that the original intention of the nikṣepa technique is a truly scientific approach according to modern standards: of an important word appearing in a title or text the whole range of meanings is first explored according to a fixed system without regard to its meaning in the relevant position or passage - just as we should, when investigating e.g. a philosophical term, first enquire after the original meaning of the word - perhaps a concrete thing - and consider possible other acceptations. What, however, seems obvious to us but is characteristically absent is the historical viewpoint, the idea of a development of meaning and meanings. Besides, we may criticise that the investigation strays too far from the actual exegetical task, losing itself in sidetracks and digressions - not, however, completely, for in most cases the return to the starting point is formally accomplished by stating that in the present case we have to do with such and such of the meanings examined; this is expressed by adhikāra with the instrumental of the object.

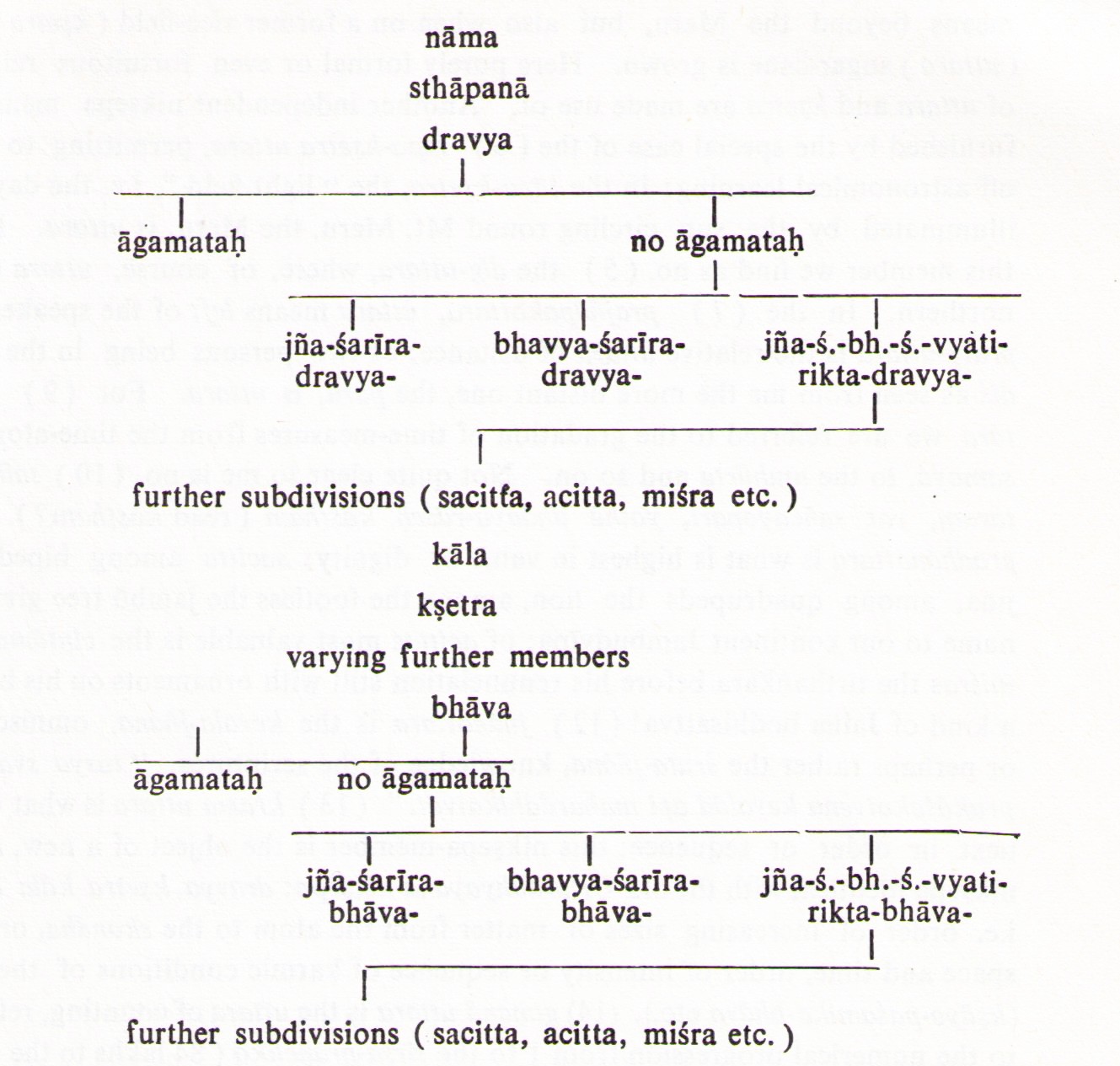

Fig. 1. Fully developed nikṣepa scheme

Now in actual practice it must soon have become apparent that the first two members of the fourfold, the catuṣka-nikṣepa, were of rather limited usefulness. Very little could be done with no. 1, nāma; but also the sthāpanā, the effigy, proved relatively unproductive and besides made difficulties in the frequent cases of abstracts, where it became necessary to have recourse to artifices such as the recognition of its written akṣaras as effigy of the nikṣepa word, or reference to the use of a concrete symbol as a substitute, with a standing reference [457|458] to the curious practice of Jaina monks to set up as a symbol of the absent ācārya a cuttle-bone called sthāpanâcārya. Moreover, a good deal of sophistry was needed to prove that the sthāpanā, which after all was a material thing, should not simply come under dravya. Nevertheless, nāma and sthāpanā have always maintained their place at the beginning of the nikṣepa - the number of nijjutti stanzas beginning with the words nāmaṃ ṭhavaṇā is legion -, but in the explanation of the commentaries they are as a rule barely mentioned or simply passed over.

Conversely, the two really important members, dravya and bhāva, were developed in a rather strange way. Both were subdivided into āgamataḥ and no āgamataḥ, literally: “doctrinally, canonically or not”, practically amounting to “jaina” and “non-jaina”. This distinction may have been an improvement or progress from the religious point of view, but for the exegesis it merely led to unproductive intricacies, if not absurdities. Instead of further theoretical explanations, I quote, as a specimen of style, a passage from the nikṣepa of the word āvaśyaka which, coming at the beginning of the first, the āvassaya-nijjutti, may be called the first nikṣepa and at any rate is the locus classicus for the full description of nikṣepa technique.

“Now [1] what is that āgamato dravyāvaśyaka? It is one by whom the text called āvaśyaka has been learned, remembered, won, measured (through knowledge of the numbers of verses, words, sounds etc.), made his own - with the right title, right accents, no syllable wanting, no syllable in excess, all syllables in right order, not breaking down in recitation, not mixing up the words, without wrong repetitions, complete, with complete accents, with distinct articulation of all sounds from gutturals to labials; obtained through the recitation of a competent guru (not from a crammer, a karṇaghātaka, neither by self-study); such a person, who is “in” the āvaśyaka-śāstra through recitation, check-back with the guru, repetition and dharma-kathā - but not with mental penetration, he is an āgamato dravyāvaśyaka; why? because dravya is absence of mental function (an-upayoga).”

This most artificial construction is obviously only designed to bring about the combination of āgamataḥ and dravya: a man who masters the āvaśyaka correctly and with technical perfection - but with strict elimination of mental interest and understanding because these would constitute bhāva! The strange designation of a person as āvaśyaka, the identification, as it were, of a person and [458|459] a text is then justified as follows: the triad consisting of the ātman, the body occupied by the ātman, and the śabda, i.e. recitation of the śāstra without mental function, is a karaṇa of the āgama, and since by secondary application the designation of the product may be used for the cause (kāraṇe kāryopacārāt), this triad may be called āgama, and consequently the person of the mentally unconcerned āvaśyaka expert called dravyâvaśyaka.

Even more artificial - if that be possible - is the no-āgamato dravyâvaśyaka. It is of three kinds: jña-śarīra-dravyâvaśyaka, bhavya-śarīra-dravyâvaśyaka and jña-śarīra-bhavya-śarīra-vyatirikta-dravyâvaśyaka; that is to say: the dravyâvaśyaka of the expert-corpse, the dravyâvaśyaka of the future body and the dravyâvaśyaka distinct from these two.

I quote:

“Now [2] what is the material āvaśyaka of the expert-body? It is as if somebody, seeing on a couch or a layer or on the place of study or on the siddha-śilātala the body of an āvaśyaka-expert from which the soul has departed, disappeared, gone to another existence, which it has abandoned - were to say: 'Oh! By this body-mass the āvaśyaka was formerly taught, proclaimed, described, explained, interpreted, commented upon like - what simile is there? This was formerly a pot full of honey, this was formerly a pot full of ghee'.”

That means: in the corpse there is now no longer any bhāva, so it is dravya, and no longer any āgama, therefore no-āgamataḥ; in the pot there is no longer any honey or ghee. Conversely - omitting the exactly parallel details - the bhavya-śarīra is the body of a man who at some future time will be knowing the āvaśyaka, who has not yet bhāva and āgama - an empty pot in which at some future time there will be honey or ghee.

As against these artificialities merely filling up the scheme the no-āgamato jña-śarīra-bhavya-śarīra-vyatirikta is the only real and relevant part of the dravyâvaśyaka. But as in the case of nāma and sthāpanā, the road once taken, though hardly leading to a desirable goal, was stubbornly kept to: the scheme just described for āvaśyaka is mechanically repeated for any other nikṣepa, the catchwords jña-śarīra and bhavya- śarīra being quoted without any application and explanation and the vyatirikta alone being of practical significance. In the case of āvaśyaka, this vyatirikta is further subdivided into laukika, kuprāvacanika and lokottara: laukika, “worldly”, is the āvaśyaka morning toilet (dravya in [459|460] so far as cleaning the teeth etc. has nothing to do with bhāva, is free of bhāva), kuprāvacanika is the worship of non-Jaina gods (which of course lacks the right bhāva), lokottarika, “spiritual”, is the performance of āvaśyaka rites by bad, undisciplined Jaina monks (therefore no-āgamataḥ!).

Everything becomes simpler and more natural when we now come to the bhāvâvaśyaka. Āgamataḥ this is now the person of an āvaśyaka expert with mental activity and understanding, a jānaka upayuktaḥ; no-āgamataḥ has the same subdivisions as dravya no āgamataḥ, but now the vyatirikta laukika is the recitation of the Mahābhārata in the morning and of the Rāmāyaṇa in the afternoon, and so on and so on. It seems to me not improbable that the scheme of exposition was originally developed for bhāva, and that it was its extension to dravya which led to such absurdities as the corpse of the one-time expert etc.

It would be natural to assume that it was dissatisfaction with such artificialities and with the unproductiveness of the initial members of the original catuṣka-nikṣepa which led to or at least contributed to its amplification by inserting new members between dravya and bhāva. But this is certainly not the whole story. The first and most important members to be added in the nijjuttis were kṣetra and kāla, space and time. Now in three passages of the Uttarādhyayana [3] we find what may be called an embryonic nikṣepa consisting of the four members dravya, kṣetra, kāla, bhāva; 30, 14, a fifth member, paryāya, is added (after bhāva, which in the nijjuttis always remains the last member!), but nāma and sthāpanā are completely absent. There can be no doubt that all three passages, belonging to one of the oldest texts of the canon and written in the old śloka metre are very much older than any nijjutti or allied text where the “classical” nāma-sthāpanā-nikṣepa appears. Shall we conclude that nāma and sthāpanā were a later invention, that their addition to the older Uttarādhyayana nikṣepa caused the omission of kṣetra and kāla which were afterwords re-introduced, though not compulsorily? All this does not sound very convincing; I confess my inability, for the time being, to offer a satisfactory explanation of the origin and early history of the classical catuṣka-nikṣepa and can only hope that further investigations will shed more light on it.

At any rate, the development of the classical nikṣepa did not stop with the addition of kṣetra and kāla. Finally, the original idea of a fixed scheme to be applied to any given word was virtually abandoned, and whole strings of new [460|461] members were inserted the choice or invention of which was governed by the needs and possibilities of the individual case, merely depending on the inventiveness and acumen of the ācārya. The nikṣepa of uttara coming at the beginning of the Uttarādhyayana-nijjutti has no less than 15 members and may serve as an example.

(1) noma and (2) sthāpanā are barely mentioned; for (3) dravya the scheme explained above (see Fig. 1) is quoted, but only the no āgamato jña-śarīra-bhavya-śarīra-vyatirikta is applied and explained. It is of three kinds: sacitta, acitta and miśra - a favourite subdivision in the nijjuttis. sacitta dravya uttara is the son relatively to the father, acitta dravya uttara is dadhi relatively to fresh milk, miśra the body of the child - consisting of animate parts and inanimate parts such as hairs and nails - relatively to the body of the mother. In these cases, uttara might be understood as “later”, but their place in the nikṣepa scheme was determined not by the temporal aspect but by their common dravya quality. [461|462] (4) kṣetra uttara is found in the name of the kṣetra Uttarakuru, where uttara means beyond the Meru, but also when on a former rice-field (kṣetra) later (uttara) sugar-cane is grown. Here purely formal or even fortuitous relations of uttara and kṣetra are made use of. Another independent nikṣepa member is furnished by the special case of the (6) tāpa-kṣetra uttara, permitting to show off astronomical learning: in the tāpa-kṣetra, the “light field”, i.e. the day zone illuminated by the sun circling round Mt. Meru, the Meru is uttara. Before this member we find as no. (5) the dig-uttara, where, of course, uttara means northern. In the (7) prajñāpakottara, uttara means left of the speaker. (8) praty-uttara is the relative uttara of distance: of two persons being in the same diś as seen from me the more distant one, the para, is uttara. For (9) kālottara we are referred to the gradation of time-measures from the time-atom, the samaya, to the muhūrta and so on. Not quite clear to me is no. (10) sañcayottaraṃ, yat sañcayopari, yathā dhānya-rāśeḥ kāṣṭham (read koṣṭham?). (11) pradhānottara is what is highest in value or dignity: sacitta among bipeds the jina, among quadrupeds the lion, among the footless the jambū tree giving its name to our continent Jambudvīpa; of acittas most valuable is the cintāmaṇi, of miśras the tīrthaṅkara before his renunciation still with ornaments on his body - a kind of Jaina bodhisattva! (12) jñānottara is the kevala-jñāna, omniscience, or perhaps rather the śruta-jñāna, knowledge of the scriptures, “tasya sva-para-prakāśakatvena kevalād api maharddhikatvāt.” (13) krama uttara is what comes next in order or sequence: this nikṣepa-member is the object of a new, a sub-nikṣepa identical with the old Uttarādhyayana-nikṣepa: dravya kṣetra kāla bhāva, i.e. order of increasing sizes of matter from the atom to the skandha, order in space and time, order of intensity or sequence of karmic conditions of the soul (kṣāyo-paśamika-bhāva etc.). (14) gaṇanā uttara is the uttara of counting, referring to the numerical progression from 1 to the śīrṣa-prahelikā (84 lakhs to the power of 28). And lastly, after so many and artificial members, the last: (15) bhāvottara renounces every division and subdivision and merely states: bhāvottaraṃ kṣāyiko bhāvaḥ, i.e. the highest of the karmic soul-conditions. The uttara-nikṣepa ends with the statement that in our case we have to do with the kramottara (kramottareṇa adhikāraḥ), the chapters of our work being called uttarāṇi because they follow the Āyāraṅga.

It will be seen that though there is no lack of sophistry and fruitless ingenuity, such a nikṣepa might be said to be on the way to a full-grown dictionary article that might be regarded as a useful contribution to lexicography even by modern standards. To the - not unjustified - objection that some of the members might be comprised within others our ācārya replies that after all everything could be included in the fourfold original nikṣepa: where members are given in excess of the nāmādi-catuṣṭaya this is done for the mental training of the students and in order to show of all things what is in them common or individual or [462|463] both. To this apology is added an elaborate scientific justification of the nikṣepa method as such which shows that the Jainas must have had difficulties to maintain their old inherited method against the criticism of more progressive rival schools. At the same time, the nikṣepa had apparently reached the possible limits of its development and gradually fell into disuse. [463]

Aṇuogadārā sutta 13: se kiṃ taṃ āgamao davvāvassayaṃ? āgamao davvāvassayaṃ jassa ṇaṃ Āvassae ti padaṃ sikkhiyaṃ, ṭhiyaṃ, jiyaṃ, miyaṃ, parijiyaṃ - nāma-samaṃ ghosa-samaṃ ahīn' akkharaṃ aṇaccakkharaṃ avvāiddh' akkharaṃ akkhaliyaṃ amiliyaṃ avaccāmeliyaṃ paḍipuṇṇaṃ paḍipuṇṇa-ghosaṃ kanth' oṭṭha-vippamukkaṃ guru-vāyaṇovagayaṃ, se ṇaṃ tatthe vāyaṇāe pucchaṇāe pariaṭṭaṇāe dhamma-kahāe, no aṇuppehāe, kamhā? “aṇuvaogo davvam” iti kaṭṭu.

Aṇuogadārā sutta 16: se kiṃ taṃ jāṇaya-sarīra-davvâvassayaṃ? … āvassae tti pay' atthâhigāra-jāṇagassa jaṃ sarīrayaṃ vavagaya-cuya-cāviya-catta-dehaṃ jīva-vippajaḍham sejjā-gayaṃ vā nisīhiyā-gayaṃ vā siddha-silātala-gayaṃ vā pāsittāṇaṃ koi bhaṇejjā: aho! ṇaṃ imaṇaṃ sarīra-samussaeṇa jiṇa-diṭṭheṇaṃ bhāveṇaṃ āvassae tti payaṃ āghaviyaṃ paṇṇaviyaṃ parūviyaṃ desiyaṃ nidaṁsiyaṃ uvadaṃsiyam, jahā - ko diṭṭhanto? ayaṃ mahu-kumbhe āsī, ayaṃ ghaya-kumbhe āsī; se taṃ jāṇaya-sarīra-davvâvassayaṃ.

24, 6, 7: davvao khettao ceva kālao bhāvao tahā jayaṇā cauvvihā vuttā, taṃ me kittayao suṇa : || davvao : cakkhusā pehe, juga-mattaṃ ca khettao, kālao : jāva rīejjā, uvautte ya bhāvao; 36, 3: davvao khettao ceva kālao bhāvao tahā | parūvaṇā lesi bhave jīvāṇam ajīvāṇa ya; 30, 14: omoyaraṇaṃ pañcahā samāseṇa vivāhiyaṃ : | davvao khetta-kāleṇaṃ bhāveṇaṃ pajjavehi ya (with exposition vv. 15-24).

Prof. Dr. Ludwig Alsdorf

Prof. Dr. Ludwig Alsdorf