Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

The Prakrit Jñānabhāratī International Award is presented to an eminent scholar of international recognition who has rendered a significant contribution to the development of Prakrit Studies. The award is administered by the National Institute of Prakrit Studies and Research at Śravaṇabeḷagoḷa (Karnataka, India). The Institute was established in 1993, under the aegis of the Śrutakevalī Education Trust, to propagate and promote Prakrit studies and research. Under the guidance of Śrī Cārukīrti Bhaṭṭārakajī, the Institute has begun to publish translations of the Dhavalā, Jayadhavalā and Mahādhavalā, the three celebrated commentaries on the Ṣaṭkhaṇḍāgama into Kannada. It is also publishing bilingual texts in Prakrit and Kannada to facilitate Prakrit teaching and learning. The Institute hosts seminars and workshops which focus on Prakrit, a repository of Indian Culture. With the aim of enlarging the scope of Prakrit Studies, the Prakrit Jñānabhāratī International Award was instituted in 2004; it comprises a citation, memento, and a cash prize of Rs.1 Lakh.

The first award in 2004 went to Professor Padmanabh S. Jaini of the University of California at Berkeley. In 2007 the Institute has proudly announced the awardees for the years 2005 and 2006: nestor scholars Professor Dr Willem Bollée (Bamberg) and Professor Dr Klaus Bruhn (Berlin), both from Germany and authors of groundbreaking works in Prakrit Studies. The award ceremony took place in Berlin on 25 May 2008. The text of the addresses given by Professors Bollée and Bruhn follow:

Professor Dr Willem Bollée:

Professor Padmarajaiah Hampana, Professor Prem Suman Jain, Dr Mrs Saroj Jain, dear colleagues, especially the ones formerly in Heidelberg, Professors Heidrun Brueckner, Lothar Lutze and Joachim Bautze.

I wish to first thank His Holiness Pūjya Svasti Śrī Cārukīrti Bhaṭṭāraka jī Mahāsvamījī as chairman, and the other members of the selection committee of the Śrutakevalī Education Trust and the National Institute of Prakrit Studies and Research in Śravaṇabeḷagoḷa, for the most honourable award, conferred on my person for my work in the field of the study of Middle-Indo-Aryan literature and Jain religion. So far I have worked predominantly in Ardha-Māgadhī and Jaina Mahārāṣṭrī, but since I succeeded in obtaining some more relevant texts, also in Śaurasenī and Jain Sanskrit, as the booklet will show, which is to be released later on during this function.

Asked about one's profession here, one often has to explain first that an Indologist is not a kind of medical specialist, and that the religion of the Jains is completely unknown.

According to modern brain research we have neither an I nor a free will. Be that as it may, I came to the study of the Jains only after my degree because of lack of interest in non-brahmanical India at my university just after World War II, where the professor of Indology himself had never been to India and told us that one could better study the discipline at one's desk at home.

Besides, I had begun as a student of European classics and Indo-European linguistics, for in the Latin Grammar School Greek had been my favourite discipline. On one occasion, on the last day before the Easter holidays, I was fascinated, when our teacher, with whom we read Xenophon's expedition with his Greek mercenaries to Persia, had written and explained King Darius' Behistun inscription in Old Persian on the blackboard - that king, who may also have inspired the Emperor Aśoka to make proclamations to his peoples on the same way in stone.

The so-called fate had early helped my interest in oriental languages, when one day, together with a classmate, I found in a bookshop a Sanskrit grammar and we started to learn Devanāgarī. From books we also became interested in Buddhism on which my friend later wrote his thesis, whereas I worked some years on the Critical Pali Dictionary, first in Denmark, and soon after that in Hamburg, at that time the centre of Middle-Indo-Aryan, especially Jain Studies in Europe.

I used the good opportunity to participate in some courses, first on Haribhadra, then also in Ardha-Māgadhī. As in contrast to the Tipiṭaka - only a fraction of the Śvetāmbara Āgamas has been critically edited and studied, and the early editions now must be revised, I decided to further concentrate on Jinological research. At Münster university, where I was an assistant professor when my contract with the Pali Dictionary ended, my Jain studies were still combined with Indo-European linguistics; after my DLitt. degree at Heidelberg I could restrict it to comparison with other Indian religions.

After World War II the interest in the advanced civilisations of the past fast decreased, in Europe as well as in India, where we have lost a whole generation of great scholars such as A. N. Upādhye, who visited me in Bonn in the early seventies of the last century; Mālvaṇiyā,whom I saw in Ahmedabad, and Bhāyānī. The avasarpiṇī, however, is gradually followed by an utsarpiṇī period. I am not informed about India, but in Germany we are happy now to have some promising younger students of Jainism. They, too, will want to build up a library and therefore face the same difficulties as we had, namely the procurement of books, especially the older text editions.

In the past, Jain studies used to be promoted by royalty: we think of the Mahārāja Gaekwaḍ of Baroda, and other prominent laymen such as Singhi Jain. The series they sponsored are mostly out of print now and urgently need to be made available once more. This holds true even more for the pothis and books printed in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Some of these were recently reset and regrettably not properly proofread. An additional difficulty is that nowadays Indian publishers consider reprinting a text a commercial risk. Therefore, at my suggestion, Maurice Bloomfield's digest of Bhāvadeva's Pārśvanāthacarita has now been made available again, but the text, which appeared in Benares in 1911 and of which I had provided the exemplar, is still waiting. For this reason the library of the newly founded chair of Indology in Würzburg will have to find many antiquarian books. This is a burden to its budget, all the more, because Jain studies are only a part of our discipline. Therefore, and in view of the fact that in the Indian śramaṇic religions people are always invited to dāna, I have decided to donate the prize money connected with my award to my Würzburg colleague, Professor Heidrun Brückner.

Professor Dr Klaus Bruhn:

It is a great honour for me to welcome the three Indian guests in Berlin, Śrī Ajitkumār Benadi, Prof Hampa Nagarajaiah and Śrī Prem Suman Jain. I have to greet Prof Willem Bollée and Prof Annegret Bollée and last but not least all the participants. For me this is a great event, a great event for myself and for my wife and for all the members of my family.

I extend my thanks for the prestigious Prakrit Jñān Bhāratī International Award to the Śrutakevalī Trust and to the National Institute of Prakrit Studies and Research, in particular to the head of the religious centre Jagadguru Karmayogī Svasti Śrī Cārukīrti Bhaṭṭāraka jī Mahāsvamījī. In other words, my thanks go to Śravaṇabeḷagoḷa in Karnataka. I visited Śravaṇabeḷagoḷa in the fifties, not knowing how important the place would be for me at a certain occasion in my later life.

Do I deserve the award? I shall try to describe in a few words my study of Jainism. We do not have in Germany departments of Jaina Studies. But as you probably all know there have been several great scholars in Germany, who started the study of Jainism and who have made pioneering and significant contributions to the study of Jaina literature. More than that. These scholars, some at least, tried to supply an overview of sections of the vast Jaina literature. Here is one of the main tasks, the consolidated study of important portions of the literary cosmos. To this day the problem has not been solved. After the time of the pioneers, the interest was mainly concentrated on individual texts. As a consequence we have systematic studies of works belonging to different genres, but it is always the individual work that has been studied rather than a group of works. We need, excuse me for theorizing, a shift from Singular to Plural. It seems that that could only be done by giants like Albrecht Weber, Hermann Jacobi, Ernst Leumann, Walther Schubring, Muni Puṇyavijaya and A.N. Upadhye. Today great projects are dreams. Perhaps the Śravaṇabeḷagoḷa Institute (the National Institute of Prakrit Studies and Research) will be able to follow this line in the case of Karma-literature with its extensive commentaries, Dhavalā etc. We are looking forward to the expected publications.

My own career was a simple one. I was a student of Professor Ludwig Alsdorf in the University of Hamburg. Ludwig Alsdorf (1904-1978) was the successor of Walther Schubring (1881-1969). Schubring had devoted his entire life to the study of Jainism. Alsdorf followed him but was equally interested in Buddhism and Vedic religion. Alsdorf had secured manuscripts of an ancient Prakrit text. This was just an episode in his life. But he asked me to analyse this particular text (author Śīlāṅka) by way of a comparison with a parallel Jaina text in Sanskrit. This parallel existed in the form of the famous Triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacaritra by Hemacandra (1089- 1172), the universal history, mainly a biographical corpus of the lives of the 24 Jinas or tīrthaṅkaras. I prepared such a comparison, producing on the whole an overview of the Śvetāmbara tradition with its major and minor branches.

But unfortunately I did not include an overview of two important Digambara texts, one by Guṇabhadra and one by Puṣpadanta. An edition of Śīlāṅka's voluminous text (probably 9th century), in other words of "my" text, was later on prepared by Pt. Amritlāl Mohanlāl Bhojak.

What we need today is an introduction into the universal history, into the entire ensemble, canonical and postcanonical, Śvetāmbara and Digambara, Prakrit and Sanskrit, a primer as it were. But although the details have largely been studied, such a primer will never be written. The very word "primer" does not seem applicable to such material.

The study of the universal history (my thesis) is in a way a simple subject, but even then I mentioned here some details for which I hope to be excused.

My academic career was largely determined by my "Gurus". When I was granted a scholarship for a stay in India from 1954-1957, my Guru Ludwig Alsdorf suggested that I should study on the one hand the two Daśavaikālika-Cūrṇis and on the other hand certain iconographic Jaina motifs (devotional objects, often cosmographic) like Samavasaraṇa, Meru, and Nandīśvaradvīpa. But in India I met Dr U.P. Shah (1915-1988), the great authority for Jainism in Baroda who had himself collected material for such an iconographic study (unfortunately unpublished) and who suggested that I should rather study the Jaina art of Deogarh in Uttar Pradesh. This I did and the Cūrṇi project was not continued.

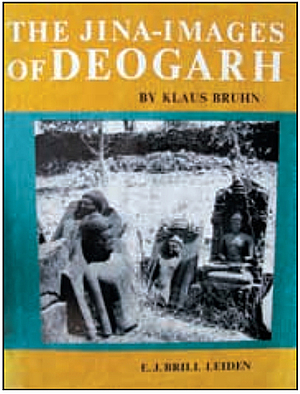

Deogaṛh means "fort of the gods", and there are many places with this name in Northern India. "My" Deogarh, to put it again in this way, was in the Lalitpur District of Uttar Pradesh, approximately in the middle between Agra and Bhopal. This locality has Hindu and Jaina remains, in the first place the famous Viṣṇu Temple or Gupta Temple. There are many Hindu remains besides the Gupta Temple, but there is also a cluster of Jaina temples on the hill to the southeast of the small village of Deogarh. The Jaina temples on the hill, ninth to twelfth centuries, were to become my subject, my field of research, my "paradise", for many months to come. There were thirty-one Jaina temples, mostly of a simple architectural type but of different sizes. But there were in particular hundreds of Jaina sculptures, mostly Digambara Jinas, in other words naked Jinas, standing or seated. There were also other Jaina statues, especially representations of the Jaina goddesses Ambikā and Cakreśvarī: Ambikā - a goddess with a child or with children (a mother-goddess), Cakreśvarī - a goddess with many arms and weapons, mainly disks (a belligerent goddess). I myself had to concentrate on the Jina images, as you can see from the book lying on the table. I have unfortunately not studied the other material which is fairly rich.

Nobody has visited Deogarh without taking a glance at the river Betwa or Vetravatī. The river creates one of the most picturesque sceneries in Central India, and I wish I could show you a slide. I think foreign tourists are always welcome in Deogarh, but accommodation has to be planned in advance. But that is not our subject. I have studied the place, in particular the Jina images, for many years. The Deogarh book was published in 1969 when I was already a professor at the Free University of Berlin. The Jaina art of Deogarh is not isolated. There are similar images in the surrounding area, even at some distance, e.g. cut into the steep rock of Gwalior. See my article in Kurt Titze's "Pictorial Guide" to Jainism.

Forty years after Deogarh:

I have recently studied Jaina miniature paintings from western India, and I have for many years after Deogarh studied Jaina iconography (some efforts successful, perhaps in need of revision). But, in continuation of my thesis I have studied once more Jaina literature, this time early Jaina literature.

In the nineties I concentrated on the five mahāvratas, the five vows or commandments, comparable to similar constellations in other religions, in particular comparable to the Ten Commandments of Christianity. In early Jainism, the five vows are found, completely or in parts, in many different Jaina works. The matter is important, inter alia because Mahāvīra mentions five vows: nonviolence, truth, abstention from theft, chastity, and nonpossession or poverty (I-V); whereas Pārśva, the predecessor of Mahāvīra, the 23rd tīrthaṅkara, mentions four vows (i-iv), an unexplained difference. But it is not only a question of four or five - of this well known historical distinction. There are very many synonyms for the five vows (different words for the same vow), there are more rigid forms of the vows for monks and less rigid forms of the vows for laymen, there are extended forms and reduced forms of the configuration, there are explosions of the description (endless enumeration of varieties of a particular vow), and there are combinations of the five vows with totally different concepts. All this is somewhat complicated but not absolutely incomprehensible for the non-specialist.

Statue of a Jina, main idol of Temple Number 15 near Deogarh, 1954 (Bruhn 1969: 299). Photo by the author.

Incomprehensible is another subject, the almost legendary Āvaśyaka literature. There are six āvaśyakas or rules or duties, including the obligatory recitation of a praise of the twenty-four Jinas or tīrthaṅkaras. All that seems quite natural. But, for unknown reasons, the six small rules or texts have produced an immense body of literature, mainly dogmatical. Our friend Prof Bansidhar Bhatt, Professor emeritus at the University of Münster, is perhaps the only scholar who really knows this literature. The study was started by Ernst Leumann (1859-1931) in Strasburg, but Leumann had no successor for Āvaśyaka Studies, with this one exception. Let us hope that Bansidhar Bhatt will make good progress in his Āvaśyaka Studies. Others, including myself, have apparently not had the courage to enter, after Ernst Leumann, the impervious jungle of the Āvaśyaka literature.

An award is often linked with cash. As you know, the present prize is also connected with a presentation. I now have to say where the euros of my award (one lakh rupees) will go. One half will go to the Children's Hospital at Śravaṇabeḷagoḷa, and one half will go to the Loomba Trust and Foundation, founded in 1997 by Raj Loomba. This foundation is a charity founded to benefit impoverished women and children around the world.

References:

Bruhn, Klaus. Śīlānkas Cauppaṇṇamahāpurisacariya. Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Jaina-Universalgeschichte. Hamburg: De Gruyter, 1954.

Bruhn, Klaus. The Jina-Images of Deogarh. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1969.

Bruhn, Klaus. "Āvaśyaka-Studies I." Studien zum Jainismus und Buddhismus (Gedenkschrift für Ludwig Alsdorf). Ed. K. Bruhn & A. Wezler, 11-49. Universität Hamburg: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1981.

Bruhn, Klaus. "Five Vows and Six Avashyakas: The Fundamentals of Jaina Ethics." Ed. C. Geerdes, 1997-1998. http://here-now4u.de/eng/spr/religion/ Bruhn.html.

Bruhn, Klaus. "The Mahāvratas in Early Jainism." Berliner Indological Studies 15/16/17 (2003) 3-98.

Titze, Kurt. Jainism. A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 1998.

Website: www.klaus-bruhn.de

Prof. Dr. Klaus Bruhn

Prof. Dr. Klaus Bruhn

Prof. Dr. Willem Bollée

Prof. Dr. Willem Bollée