At the end of the Second World War, Japan found itself in a state of total disintegration. Then, moved by deep patriotism, the Japanese people set to work. The American industrialists extended to them their sympathetic cooperation. At that time, too, the Americans worked five days in the week, but the Japanese worked for six, for 10 hours a day. Work for them was not merely a means of earnings their livelihood; rather they were inspired by a great dream—that of national reconstruction. Work symbolised their determination to raise their fallen country to new heights. The American industrialists counselled the Japanese to observe a five-day working week. The Japanese did not quite understand what the American meant. It was then explained to them that they would receive full salary for the week, even though they would work for five days only instead of six. At this the Japanese were aghast and they opposed the move tooth and nail till it was withdrawn. They wanted to make their country great and this could only be done by hard and sustained work. Soon the Japanese found their feet, confidently marching towards complete rehabilitation.

The Japanese put in long hours of work every day. Some time back, the Japanese Government offered to provide some relief to the hard—working citizens by reducing their daily workload. But the workers would not hear of it. "If we turn out less work, it might burden other people."

The Sarvoday leader, Jai Parkash Narain, accompanied by some foreign friends, visited an Indian village. There they found people sitting in groups of five to seven, gossiping away their time. The foreigners found it very strange. They said, "J.R, Yours seems to be a very rich country!" When J.R looked up in surprise, they said, “The people of a poor country cannot afford to sit idle like that!" J.P. explained that the people sat idle because the ploughing time was yet far off. But his friends were not convinced. They said, “How is it possible that there is no work to be done? If only people have a definite aim, they will find plenty to do."

Here are presented two snapshots of India and Japan—the Japanese approach contrasted with the Indian mentality. On one side, we have willing renunciation of amenities offered, on the other total reluctance to engage in work. How cans nationalism thrive in the face of such indifference? The absence of any nationalistic fervour is accounted for by increasing selfishness. As long as men is attached to material things, giving undue importance to the self, ignoring human values, his Social and national consciousness would remain dormant, without even a remote possibility of a religious or spiritual awakening. He, who truly understands religion and lives it, can never be so selfish, comfort-loving and apathetic to work. It is therefore all the more necessary to strengthen and uphold the fundamental values of religion.

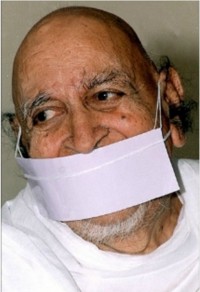

Acharya Tulsi

Acharya Tulsi