Lord Mahavir initiated Megh Kumar, the son of Emperor Shrainik. Prince Megh was intelligent, wise, and full of discretion. He knew a great deal, but he did not know anything about the routine of a monk’s life. What should a monk do? In what manner? He approached Lord Mahavir and said, "Respected Sir, l’m now in your custody. After having found refuge in you, l‘m fully content. No fears assail me now but l am ignorant. Kindly guide me as to how I should walk, how sit or stand? How to think? How to eat? How to speak?" Muni Megh had a definite purpose in asking these questions. He wanted to do something, become something. Curiosity, hunger, the will to do something—these three things are linked with the life-instinct. The man who wants to live a purposive and meaningful life, in accordance with his ideal conception, must of necessity adopt a certain way of living.

Lord Mahavir looked into the questioning eyes of his new pupil, and saw sailing there wonderful dreams. The desire to embody these dreams into reality had made Muni Magh speak Lord Mahavir sought to gratify his pupil's inquisitiveness thus:

"Son! To embrace ascetic does not mean that a man shall renounce eating and drinking, clothing, strolling about or sleeping and other urges like that. A corporeal being cannot renounce these. And yet it is necessary that every act of his be different from that of a householder. A seer is he who uses every commodity in his own way, not like the householders. Here is the dividing line that is expressive of the difference in the life—styles of a monk and a householder."

Lord Mahavir gave Muni Megh permission to fulfil his natural urges, but then he must do so consciously and in moderation. Moderation connotes control. Any action for the development of self-control cannot but be disciplined. To move with consciousness is to practise the yoga of walking. This in itself is a discipline. The scriptures mention four different forms of awareness—the consciousness of matter, the consciousness of space, the consciousness of time and the consciousness of being. Material consciousness implies seeing with one's eyes; consciousness of space, concentration on just that much ground one has to traverse; consciousness of time implies no definite period of time, but walking with full awareness as long as one does so; in the case of loss of eye—sight, however, the sadhak may walk under the supervision of fellow—sadhaks; consciousness of beings implies walking properly.

The word ‘properly’ is very important. Whatever inclination the sadhak prusues, he must put into it the whole of his mind —i.e., if he does it wholeheartedly without any distraction, he can even enter the state of samadhi. While shedding light on the concept of propriety in gaman—yoga, the yoga of walking, the learned author of the scriptures says:

"The avoidance of the sense-objects, the abandonment of five kinds of effort, total absorption or complete identifications with the act of walking in gaman-yoga, giving it top priority this is the description of proper walking or walking with one's whole being. Such walking with full consciousness is spirituality. So a sadhak must needs be very alert while performing the act of walking."

Gaman yoga (the act of walking) is indeed the touch-stone mania inner pilgrimage. Only he passes the test that does not walks too fast (as if he is on the run), does not speak or laugh or eat while walking, and does not gaze at others absentmindedly while walking.

The sadhak who is agitated, impatient or restless while waking, or who keeps his gaze fixed up or down, who indulges in self—talk, fails the test.

As in the posture of walking, there is a proper way of standing, sitting, sleeping, speaking or eating. Great alertness is required there, too. An alert sadhak becomes immediately aware of his negligence. One, who becomes aware of his negligence, is negligent no more. lt is, therefore, necessary that every movement of the sadhak should be fully conscious and restrained. That is the mark of his success.

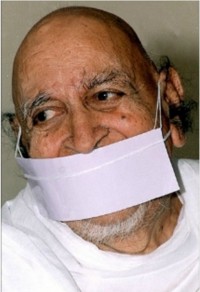

Acharya Tulsi

Acharya Tulsi