In fact, for all his frugal way of life, Meghjibhai was most hospitable and generous. He would often invite his English friends to lunch at a vegetarian restaurant, Country Life, in Queen Victoria Street (it has since closed down). Mr. J.K. Gohel well remembers this: 'It was Meghjibhai's favourite restaurant. To start with his English friends came very enthusiastically to have a vegetarian lunch but gradually their enthusiasm waned. Meghjibhai could not even imagine that people would relish non-vegetarian food rather than the tasty vegetarian food. Meghjibhai took a personal interest and ordered the very best dishes. But he was not prepared to give up his principles for the sake of his guests.'

He stuck proudly to his principles. To those who did not know him well this could seem like arrogance but his strict attitude was limited to himself. He was not at all interested in impressing others by his personal principles or his status and he preferred not be singled out for special attention, whether at a social function or a business meeting. Mr. Gohel writes 'Whenever he came to a dinner party at my place he did not like it if we accorded him special honour as a respected guest. He treated us as if he was a member of the family and he expected us to treat him in the same way. At his own house he treated everybody, from a multimillionaire to a clerk, with the same fellow-feeling and modesty.'

Mr. C.P. Shah remembers his modesty: 'Meghjibhai gave more importance to simplicity than to his status. Although he had a car at home he would use the underground train to go to his office from his home. He would choose a seat facing the direction in which the train was travelling. Once I asked casually "Why don't you take a seat facing the rear: it is more convenient?" He said "I like to look forward in the direction in which we are going ahead, in which we are progressing. It would give me a headache to look the other way".'

He had a marked sense of duty and punctuality. He would always be at the station on time. Often, in the winter, if the weather was bad other people would miss their train but Meghjibhai was unfailingly there in his preferred seat on his particular underground train. If he were invited to a function or a dinner party and the host calculated that the guests would (in the Indian tradition) be fifteen or twenty minutes late, Meghjibhai was sure to upset the host's calculations. He would turn up dead on time and if the host were not ready the host would be shamed by his punctuality. 'Punctuality' it is said 'is the politeness of princes'. Meghjibhai was a wealthy and important man but he was not prepared to neglect small courtesies.

He was equally punctilious in business. He stood out against any kind of concession or special price. He would come straight to the point without beating around the bush or haggling. He stuck firmly to the principle ' A bargain is a bargain'. Mr. C.P. Shah once asked him why he was so strict. His reply was frank and straightforward, 'Chandubhai, all the profits from these transactions will go in donations. So, what is wrong if I try to increase the income of my charitable trusts?' He was more greedy for the sake of his charitable donations than a man would generally be for his own profit. Once he had made a bargain, if he knew that he had made a mistake he would freely admit it and agree readily to redress the situation. W hat was important to him was that the beneficiaries of the charity should get a good, but honest and fair bargain. He was not trying to show that he was a clever businessman; indeed his reputation was such that it was not harmed by open admission if he should make a mistake. Those are Mr. C.P. Shah's memories of Meghjibhai. In this connection Mr. Gohel writes, 'To err is human. A large number of great men make small or great mistakes in their lifetime and it would be going too far to suggest that Meghjibhai was an exception to this. Sometimes a wrong decision was taken in haste or a wrong estimate was made, but with his quick intellect he would himself be the first to detect his mistake and he would frankly admit his mistake to his friends and colleagues. He would not try to conceal his mistake but would put it right immediately at whatever cost.'

His personality and principles were not affected by living in London. He kept himself immersed in his work and did not try to stray into fields of which he had no knowledge. He had no spare time for other matters so he was rather ignorant of many aspects of London life. Mr. Gohel recalls a rather amusing incident: 'Some businessmen from the West End of London came to Meghjibhai with a proposal that he should invest some money in a "strip club". Meghjibhai, however, was quite ignorant of this. I was present when the business talks were going on. According to his custom Meghjibhai estimated the figures for the investment, the return and the profit or loss and he was very satisfied with this business venture. Then I suggested that we would give a definite reply to these businessmen after a day or two. As was his nature, Meghjibhai came to a rapid decision but on this occasion I restrained him. After the visitors had left I asked Meghjibhai "What is your idea of a strip club?" He said, "It is perhaps something like a restaurant working on a commercial basis, or a social institution". Since I had a little more knowledge about this, I explained it to him. He was so thunderstruck to hear this that the expression on his face would have made anyone laugh. The businessmen could hardly have reached their office before we telephoned them that we had no interest in their scheme. Then Meghjibhai said to me "Do such things really go on in the world?"

I replied seriously "Unfortunately I have heard that such things definitely do go on!"'

Meghjibhai had a subtle sense of humour and could easily laugh at himself. In 1930 he went to Japan, his first trip abroad since he had settled in Africa. Somebody was curious and asked him why his partners selected him to go to Japan since he had no knowledge of English. He replied 'I know ten words of English but my partners know only two words. So among us I am the best qualified!' Actually he was exaggerating his ignorance for he did have a good knowledge of English. He was well able to unravel the intricacies of confusing legal documents and often to suggest useful amendments or additions.

Nobody could surpass Meghjibhai's skill at mental arithmetic. He could do complicated calculations involving hundreds of thousands of rupees in his head but he would never misuse this facility in order to cheat anybody. A bargain, he felt, should be made in such a way that both parties gain from it: the idea of making a profit at the expense of the other person is not business. He would think carefully before he made a promise. It was his invariable rule that promises, once given, should be kept, and a promise, which cannot be kept, should not be given. Once he gave his word, even verbally, that was as good as a signed and sealed legal document. In business transactions he expressed himself clearly and accurately so that no confusion or misunderstanding could arise at a later date. If he ever suspected any dishonest y he would drop out of the transaction immediately and he would never allow himself to be swayed by another's influence into taking any dubious or dishonest step.

Regarding Meghjibhai's character Mr. Gohel writes, 'If there was a defect in Meghjibhai's character it was only this, that he could not express his feelings adequately in personal relations. He experienced difficulty in expressing his feelings about family matters or outside affairs. As a result many misunderstood his real nature. On account of his outspoken nature those who only came into superficial contact with him found him unsympathetic. Only those who came into close contact with him knew how deep his real feelings were. He expressed them not in words but in actions. He had many bitter experiences in life and it was only after he had found a person to be trustworthy that he would place complete reliance on him. He never insisted on forcing his opinion on others. He would patiently hear everyone even if he did not agree subsequently. He took decisions on the basis of his own judgement but it was not in his nature to force his views on others.'

Idleness was not a word in his dictionary. He kept up his habit of going for an early evening walk. He walked fast, so fast indeed that he shamed his younger companions and his friends found they had to run to keep up with him. He was very fond of walking and although there were plenty of means of transport in London he went on foot whenever possible, resorting to a vehicle only when the distance was too great. On account of his regular and simple ways he kept in good health until the end of his life. One person who had close contacts with Meghjibhai in his London years was his son-in-law, Madhoo Mehta, who married Meenal. Madhoobhai remembers Meghjibhai asking him if he wanted to be treated as a son or a son-in-law. In an Indian family a son-in-law has a privileged position. He said, ‘As a son'. Once Meghjibhai was angry, for he could be a tough teacher, and Maniben interceded, 'Remember he is your son-in-law'. 'But he wanted to be treated as a son', Meghjibhai retorted. At the end of the day, though, his love would always show through.

After he settled in England, Meghjibhai, kept in touch with India and visited it every couple of years or so. While he was in India in late 1959 and early 1960 the new State of Gujarat came into being. Meghjibhai was anxious to do something for the benefit of the whole of this new state of Gujarat and approached leading figures in the government with an offer of twenty million rupees for the development of the state. He asked the political leaders to draw up a detailed plan for the use of the money. However, they were unable to take advantage of Meghjibhai's generosity, and ran into heavy weather in trying to draw up a plan for utilising the donation, so the State of Gujarat lost a valuable chance.

Maniben M.P. Shah Women's College of Arts and Commerce, Bombay

1962 was a critical year for India. The long-standing frontier disputes on the Sino-lndian border flared up and in September 1962 Chinese troops invaded India and, in spite of the gallant resistance of the Indian army, made rapid advances. There was alarm throughout the country. Pandit Nehru, prophet of peace, who had made a pact with China and had said that 'Indians and Chinese are brothers' was greatly shocked at the failure of his efforts for peace. India was unprepared for the attack, seriously lacking in armaments. Weapons were needed with great urgency. Both Britain and America started to supply these but this only partly solved the shortage: supplies from other countries also were urgently needed by the fighting troops. The great difficulty was India's chronic shortage of foreign exchange. Meghjibhai, with a spirit of patriotism offered a solution to the responsible leaders. He promised to collect in Africa as much foreign currency as possible, to be loaned to the Indian government on the sole condition that repayment should be in foreign currency. Although it was a straightforward and practical proposal the Indian Finance Ministry turned it down, after due consideration, and Meghjibhai' s scheme came to naught. The Government of India has subsequently realised the merits of such a scheme and is encouraging non-resident Indians to remit foreign exchange to India with rights of full repatriation of the money.

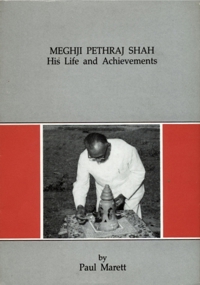

Dr. Paul Marett

Dr. Paul Marett