The M. P. Shah Hospital is Meghjibhai's biggest monument in Kenya, but there were many other donations as well. The Igerton Agricultural Hospital benefited, and another gift provided accommodation for the disabled in Thika. Although at that time many people did not believe in girls' education, Meghjibhai's outlook on this issue was progressive and he believed firmly that it was not possible to improve society without educating girls. For this reason he gave every encouragement to this aim and persuaded the Kenyan government to expend large sums of money on girls' schools, hostels and primary schools. One large donation, which he made, was the sum of 200,000 sh. for the buildings of the Maniben M. P. Shah Girls' School at Kisumu.

M. P. Shah Hospital

When it was decided, about 1952, to raise a fund for the establishment of the Gandhi Memorial Academy Society in East Africa, Meghjibhai undertook responsibility for the fund-raising. The original intention was to found a separate college but in the event the Society worked with the Royal Technical College. Meghjibhai and Hemrajbhai Nathoo Shah were trustees. The project had started with a good deal of dissension and lack of agreement on its objects. At a meeting on 28th August 1952 Meghjibhai argued vigorously for dissolving the large unwieldy committee and creating a small Provisional Committee. He carried the day and was elected Honorary Treasurer of the Fund. Meghjibhai donated a life-size statue of Mahatma Gandhi for the College, which was unveiled by the Vice-President (later President) of India, Dr. S. Radhakrishnan on 12th July 1956.

Fund-raising is not an easy task. The ability to persuade potential donors to contribute is not given to all. Patience is also essential. Often fund-raisers have to suffer insulting rejection of their approaches. A man like Meghjibhai, with self-respect, outspoken when provoked but otherwise rather taciturn, would not seem to have the obvious personality for a fund-raiser. Yet he was always successful. His own personal reputation stood him in good stead. Moreover, he would always be the first to contribute to a new fund. Adapting the dictum 'Charity begins at home' we can apply it to Meghjibhai's method of approach. He first promised his own contribution to the new fund (in this case? 10, 000) and then would make his appeal to other donors. As his own subscription was always very large, those who followed on would take this as an example and donate very generously themselves. His high reputation for probity was an added incentive to donate to any fund with which Meghjibhai was connected and he rarely met hesitation from prospective donors. Whilst some other fund-raisers had to make house-to-house rounds of likely contributors, people would come forward spontaneously to contribute to funds where Meghjibhai was concerned. Within seventeen days of opening, the fund had exceeded its target of? 125, 000.

In 1962, Meghjibhai returned to Nairobi for the wedding of his daughter, Nalini. In the short space of two months he announced donations totalling nearly a million shillings. In Thika the beneficiaries were the maternity home (50,000 sh.), and the Visa Oshwal Community (40,000 sh.); the M. P. Shah High School, a primary school and a boys' hostel received 300,000 sh. In Nairobi the Oshwal Sports Club (25,000 sh.) benefited, as did the Cutchi Gujarati Hindu Union and the Oshwal Girls' School (111,000 sh.). Meghjibhai never forgot the country where he had spent more than half his life and where he made his name and fortune. It had always been his intention to start new social projects in Kenya. After Kenya became independent in 1963 Meghjibhai had made up his mind to help in the plans, which the Kenyan government was making for the welfare of its people. His early death prevented him from carrying out his intentions. However, his family wanted to perpetuate the work which he had begun and it was announced that the Meghjibhai Foundation would donate? 100, 000 towards the setting up of health centres in Kenya; as a first instalment, a cheque for? 12, 500 was presented to Jomo Kenyatta, the President of Kenya. In addition a further very large donation was given towards the M. P. Shah Wing of the Nurses Horne in the Kenyatta National Hospital.

Vipin, Khetsibhai, Jaya, President Jomo Kenyatta and Hemrajbhai

During the years when Meghjibhai was planning his retirement from business, a great change took place in the situation of his home country. In the memorable year 1947 India had achieved independence. It was an occasion of great rejoicing, both at home in India and amongst the Indian expatriates living in East Africa and elsewhere. After nearly two centuries of foreign domination, India now had the chance to stand on her own feet, to progress on the difficult path of independence and to raise the standards of education, social welfare and the economy to those of the advanced nations. Many problems arose but India was fortunate in having the able leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru to tackle them.

For Meghjibhai, Indian independence came as an opportunity to serve his motherland. Circumstances had determined that he had to make his home in Africa. The great distance and, in the early days, poor communications, meant that he was not able to visit his home country as often as he would have liked. But his affection for India never waned and he did, when possible, return to his home village. He now made determined efforts to increase the trade of his companies with the newly independent India. In 1948, as mentioned above, he had created a charitable trust for works of social welfare in East Africa. But he longed to put to good use the great wealth which his business enterprises had brought him in the service of his own native land.

On 31st December 1948 Meghjibhai founded in Jamnagar the Meghji Pethraj Shah Charitable Trust. There were four trustees, Meghjibhai himself and Maniben, Premchand Vrajlal Shah and Meghjibhai's father-in-Iaw, Nathoo Deva Shah. Meghjibhai handed over to the Trust all his trading interests in India.

In the days before independence, Saurashtra (or Kathiawar as it was then called) was backward in many ways, lagging behind in agriculture, industry and education. Much of the region was poor compared with the more prosperous areas of India though the local rulers and lords, great or small, undertook works of social welfare each in his own way. The aims of the Charitable Trust were to improve the condition of the poorer people of Saurashtra, particularly in the fields of education and health. A programme of aid was worked out and the proposed projects (apart from provision for emergency relief works in times of natural calamity) fell into the two areas of education and health.

In the former field there were to be infant schools and primary) schools in the villages and village libraries. Girls' schools were also to be set up. Promising young people were to receive scholarships, schools and colleges for further education were to be established together with hostels for the students to live in (an important provision in a region where many students would have to study quite a long way from home). In the medical field the priorities were seen as the provision of dispensaries (in effect local health centres) and hospitals. There was a particular need for maternity homes and for sanatoria for tuberculosis sufferers.

In order to realise the objects of the Trust, co-operation with the government was necessary. After independence, the old princely rule was abolished and new states were created as the loci of regional administration. A separate state of Saurashtra was created (though it was subsequently, in 1957, incorporated in the bilingual Bombay State which was itself divided into Gujarat and Maharashtra States in 1960). His Highness Jamsaheb was Raj Pramukh (Governor) and the Chief Minister was Shri Dhebarbhai, an able and farsighted statesman. He faced a Herculean task to improve the conditions of the people of this region after centuries of poverty and ignorance, a task, moreover, which would involve the raising of very considerable sums of money. Hence when Meghjibhai' s Trust stepped in, Shri Dhebarbhai gave it a warm welcome.

History shows how frequently in India in times of crisis a man of wisdom and leadership has come to the fore and Meghjibhai was a man of practical wisdom. He brought, moreover, to his philanthropic activities a genuine commitment to the betterment of the lives of the people. This commitment, coupled with his own personality, his vision and foresight, meant that he was able to carry others with him in the implementation of his schemes.

One of his firm principles was that the projects which he funded should be established by a genuine partnership between himself and the public authorities. He devised a formula under which the Trust would share the expenditure on social welfare projects with the government. The Trust would provide one-third to one-half of the cost of new projects in the towns and one-quarter to one-third in the villages, erecting the buildings for new schools, dispensaries, hospitals, and the like. These would then be handed over to the government, which would undertake to bear the running costs. With the government' s guarantee of continued support, even in the event of political changes or if public contributions were not forthcoming, the new institutions would be protected against financial difficulties in the future.

Shortly before his retirement Meghjibhai visited Jamnagar, in Saurashtra State, and met the Raj Pramukh. It was at this time that he first expressed his wish to help the people of the State. Discussions with the government led to a programme of social welfare developments to be initiated by the Trust over a period of ten years from 1954 to 1963.

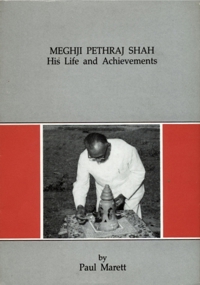

Dr. Paul Marett

Dr. Paul Marett