The colonial government was anxious to encourage the growing of certain crops, amongst them tobacco and cotton. Meghjibhai' s standing with the government was good and the Governor himself opened the cotton ginnery of a new company, Kenya Cotton and Produce Co. Ltd. (a company in the Premchand Raichand Group), at Sagana in 1936. Another ginnery also was established at Meru. The ginneries were successful even though cotton growing (unlike tobacco in which Meghjibhai was not involved) never really took off in Kenya. However, African growers supplied enough cotton to keep the ginneries going well. Now we come on to the really big venture, the one which more than any other created Meghjibhai's fortune. He had already risen, by the early nineteen-thirties, from his modest start peddling goods from door to door, to being one of the two dominant partners, perhaps the dominant partner, in a profitable industrial and trading group.

The village of Thika (now a pleasant small town) was some twenty-five miles from Nairobi. Here, on the banks of the Thika river, there were (and still are) groves of wattle trees. The bark of the black wattle is particularly rich in tannin, the substance used primarily in the process of tanning leather (but also having uses in the dyestuffs and chemical industries). The wattle trees flourish in East and South Africa and the bark can contain as much as 37% tannin. Wattle bark was a fairly important export from Kenya. Premchandbhai had already built up a small business in the export of the bark. He had installed a chopping machine in 1929 at Blue Posts near the famous and beautiful Chania waterfall just outside Thika village. Here he employed four or five men under an Indian foreman or manager. The bark was collected from local farmers, chopped and put into bags. A German firm of exporters, A. Baumann and Co., handled the export. The business prospered, though in a fairly small way.

Premchandbhai had hopes of expanding the business in wattle bark and even of establishing a factory for larger-scale production. Undoubtedly, the formation of the partnership gave the necessary conditions and impetus for development. With Meghjibhai's drive and commercial acumen the wattle enterprise leapt forward. There was no problem with supplies as the wattle trees were plentiful in the Thika area and the income was welcome to the African suppliers. The next step was the installation of new machinery to speed up the bark cutting process. The native suppliers were encouraged to start replantings of the wattle trees. Government aid was forthcoming as the project was of considerable benefit to the local economy. There were difficulties, of course, particularly the competition from the suppliers and exporters of South Africa where the wattle trees also grew in abundance. The company had to compete with these white business enterprises but Meghjibhai was never a man to be deterred by competition. This business was to prove a goldmine and was the most successful of all his ventures.

The export business in wattle bark was going well but Meghjibhai was not satisfied. At that time the bark was exported and the profitable process of extracting the tannin was carried out in factories abroad. Meghjibhai saw good prospects if the actual processing were done locally and the tannin extract were exported. Plans started in 1932. A piece of land by the river at Thika was put on the market by the government and it was secured through a nominee, Mr. G.M. Vasani, for the nominal price of 1,000 shillings. It was government policy to make land available cheaply for enterprises which would benefit the developing economy of Kenya. Setters from Britain and South Africa had benefited from this policy, obtaining agricultural land often at unbelievably low prices: many failed but many also prospered and made at the same time a contribution to Kenyan development. In the attempt to understand Meghjibhai' s success it is important to remember that, in spite of world recession, the prospects for the Kenyan economy were good, development was proceeding rapidIy and, for a man of Meghjibhai' s drive and commercial flair, opportunities were there to be seized. When the Thika land was put on sale there was same fear that a South African Company, the Natal Tanning Extract Company, would expand its activities and the colonial government of Kenya was no doubt pleased when a local business company put in an offer and acquired it. The Natal Company was already established in Kenya and in fact seems to have erected a plant at Thika about the same time as Meghjibhai.

The plans for the new factory went ahead rapidly. Meghjibhai moved temporarily to Thika while the factory was getting under way. It was two years before the large-scale machinery arrived from Glasgow and in the meantime it was necessary to struggle with small and inadequate machines. The alternative would have been to have waited until the large machines were supplied but in that time competitors would have stolen a march. The new machinery was installed in 1934: though nearly all of it has, of course, been replaced since then, it is still possible to read the words 'Thika via Mombasa' on a huge old press for baling cut bark, apparently part of the original machinery, preserved in an outbuilding of the factory today.

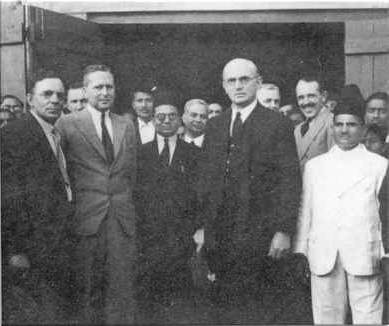

The Thika factory went into full production in 1934 and was opened by the Governor of Kenya, His Excellency Brigadier General Sir Joseph Byrne, GCMG, KBE, CB, at a large function held in one of the warehouses. Photographs still preserved at the factory show a very considerable gathering of people, with Meghjibhai and Premchandbhai prominent among them. As a sign of changing times and customs, this was the first public occasion attended by the ladies unveiled. It was also the first important function to which Africans were invited. The huge factory, with a 175 foot chimney, and covering more than 21/2 acres of land, costing 600,000 shillings to build, was the result of the dream and ambition and hard work of a far-sighted industrialist and businessman. Sound planning by Meghjibhai, backed by his close associate Premchandbhai, meant that the new enterprise flourished almost from the start. The factory made a major contribution to the family fortunes. When his partnership with Premchandbhai eventually came to an end in 1943 Meghjibhai retained this business as the principal part of his share of the assets of the former company, a wise choice indeed for the tanning extract business continued to flourish in the years to come.

Indeed, although it is no longer owned by Meghjibhai's family, the factory is still flourishing today. It is still the Kenya Tanning Extract Co. Ltd. and the 'Rhino Brand' trade mark is still used as in Meghjibhai' s day. The 33 acre site slopes steeply down to the river and the surroundings are attractive. The great hangar-like buildings are the same, though the original chimney has been replaced by a new shiny metal one. Inside, the size of the factory is apparent: it is dim and shady away from the bright African sun (electric light was installed as early as 1934) and there is a not-unpleasant sweetish smell from the extraction process. The dark-coloured bark is piled in large heaps: it still comes from small farmers, within a 60 kilometre radius, not from large estates. The railway siding and weighbridge are still in use. Two or three men operate the electrically-powered machine chopping the bark. The chopped bark is then conveyed automatically up to the boilers where it is mixed with the appropriate chemicals and the extraction process takes place. More than 50 tons of bark a day

Opening of the Thika factory, Apri11934

L.toR. Mr. W.E. Pritchard, Mr. Baumann, Mr. RaishiRupshi Shah, Meghjibhai, Sir Joseph Byrne, Premchandbhai.

are processed and the daily output is around 25 tons of tannin extract. The old open wooden tanks are gone now I replaced by shining metal vacuum boilers but the furnaces, fired with the wood from which the bark has been stripped, are still the same. The extract is tapped from the boilers as a thick dark-brown pitch-like substance which is collected in bags and weighed before it solidifies. The extract is sold either in this solid form or ground into a fine light-brown powder. Although the processes have been largely automated the factory still employs 90 men, working three shifts around the clock. In spite of the changes it is still easy to picture the scene as is was when Meghjibhai knew it half a century ago. Nowadays, as in Meghjibhai's day, the export trade is of primary importance: 95% of the factory' s output is exported, mainly to the Indian sub-continent. The export of baled chopped bark continued alongside the trade in tannin extract up to 1966 when it ceased.

Dr. Paul Marett

Dr. Paul Marett