Man is essentially a thinking or rational being. He has not only enunciated a view of life, but also inculcated a way of life. The happy combination of the view and way of life has been the distinctive characteristic of the Jain philosophy. The Jain thinkers have been extra-ordinarily meticulous in evolving a system of thought which is so rigorous and logical in its attempt. It has not allowed any illogical entry of onesidedness even by implication. Jainism, of course, is a philosophy of Anekānta. The Jains have presented not only a consistent and comprehensive philosophical system, but also propounded a number of theories in the field of science; particularly in the fields of Astronomy, Mathematics, Cosmology, Cosmogony, Physics, Botany, Chemistry, Psychology and Para-psychology etc.

All the philosophical and scientific tenets of Jainism in their original form have been discussed in some way or the other in the canonical literature in general and Bhagavatī Sūtra in particular. The whole canonical literature is mainly divided into two categories namely Aṅgapraviṣṭa (aṅga) and Aṅgabāhya. The division of Aṅgapraviṣṭa and Aṅgabāhya is a latter development. The most ancient division available in Samvāyāṅga is as Dvādaśāṅgī (Gaṇipiṭaka) and Caturdaśapūrva. By the time of Nandī, a canon, the canonical literature has been divided into three categories—1. Pūrva 2. Aṅgapraviṣṭa 3. Aṅgabāhya. Today only the latter two divisions are available in writing, while the former is not traceable. Aṅgabāhya is further sub-divided into two e.g. Āvaśyaka and Āvaśyakavyatirikta. [1]

The Aṅgapraviṣṭa canons are considered to be the nearest to the original and most authentic of all as they are composed by the principal disciples of Lord Mahāvīra. They are twelve in number: 1. Ācārāṅga, 2. Sūtrakṛtāṅga, 3. Sthānāṅga, 4. Samavāyāṅga, 5. Vyākhyā-prajñapti, 6. Jñātā-Dharma-kathā, 7. Upāsaka-Daśā, 8. Anta-kṛta-Daśā, 9. Anuttaropapātika-Daśā, 10. Praśna-Vyākaraṇa, 11. Vipāka-Sūtra, 12. Drṣṭivāda.

The thesis is based on the fifth aṅga known as 'Vyākhyā-prajñapti'. The work written in a dialogue style is called 'Vyākhyā-prajñapti'.

Besides, it is also known as Bhagavatī Viyāhapannatti, Vivāhapannati or simply Paṇṇatti. This work is more voluminous than other aṇgas. It is multifarious in its contents. Probably, there is no branch of Metaphysics, which has not been discussed in it, directly or indirectly. From the aforesaid point of view, this canon was held in high esteem. The adjective 'Bhagavatī' was, therefore, added to its original title 'Vyākhyā-prajñapti'. Many centuries before the adjective 'Bhagavatī' became a part and parcel of the title. Now a day, the title 'Bhagavatī' is more in vogue than 'Vyākhyā-prajñapti'. It is the most important work of the Ardha-māgadhi language. It is also the largest in size. It is not only a work of encyclopedic range but it is a veritable mine of the gems of knowledge, whose magnitude and depth, extension and intension are simply mind-boggling. This text contains questions and answers, between Mahāvīra and his disciples, particularly Indrabhuti Gautama. According to 'Samavāyāṅga'[2] and 'Nandī Sūtra',[3] the present canon has an exposition of thirty six thousand queries whereas according to Tattvārthavārtika,[4] Saṭkhaṇḍāgama [5] and Kaṣāya-Pāhuḍa [6] it has sixty thousand queries. It also contains material in the form of dialogue-legend. The Fifteenth chapter of the text contains legendary or semi-historical material relating to Mahāvīra's life and his relation with some of his predecessors and contemporaries. The text makes frequent references and cross-references to the aṇgas like the Prajñāpanā, the Jīvābhigama, the Aupapātika, the Rājapraśnīya, the Nandī and the Anuyogadvāra Sūtras.

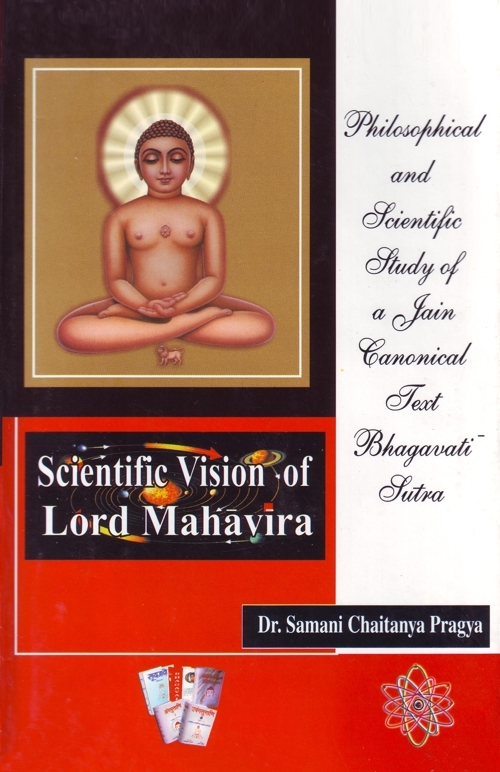

Dr. Samani Chaitanya Pragya

Dr. Samani Chaitanya Pragya