1.0 Ahiṅsā as the Foundation of Jaina Ethics

Ethical discipline constitutes an important aspect of Jainism.[1] The foundation of the ethical discipline is the doctrine of Ahiṅsā.[2] The laying down of the commandment not to kill and not to damage is one of the greatest events in the spiritual history of mankind.[3] This is for the first time clearly expressed in Jainism.

1.1 Classification of Living Being from One-Sensed to Five-Sensed Beings

The Jaina Āgama classifies living beings (Jīvas) into five kinds, namely, one-sensed to five-sensed beings.[5] The minimum number of Prāṇas possessed by the empirical self is four (one sense, one Bala, life-limit and breathing), and the maximum number is ten (five senses, three Balas, life-limit, and breathing).[7] The lowest in the grade of existence are the one-sensed Jīvas,which possess only the sense of touch and they have only the Bala of body, and besides they hold life-limit and breathing. These one-sensed Jīvas admit of five-fold classification[6], namely, the earth-bodied (Pṛthvīkāyika), water-bodied (Jalakāyika), fire-bodied (Agnikāyika) air-bodied (Vāyukāyika) and lastly, vegetable-bodied (Vanaspatikāyika) souls.

1.2 Progressive realization of Ahiṅsā: (Householder and Muni)

The entire Jaina ethics tends towards the translation of the principle of Ahiṅsā into practice. The Jaina regards as the ethical Summum Bonum of human life, the realisation of perfect Ahiṅsā. In fact Ahiṅsā is so central in Jainism that it may be incontrovertibly called the beginning and the end of Jaina religion. The statement of Samantabhadra that Ahiṅsā of all living beings is equivalent to the realisation of Parama Bṛhma sheds light on the paramount character of Ahiṅsā. Now, this idea of Ahiṅsā is realised progressively. Thus he who is able to realise Ahiṅsā partially is called a householder, whereas he who is able to realise Ahiṅsā completely, though not perfectly is called an ascetic or a Muni. It belies the allegation that the ascetic flees from the world of action. Truly speaking, he recoils not from the world of action but from the world of Hiṅsā.No doubt the ascetic life affords full ground for the realization of Ahiṅsā, but its perfect realization is possible only in the plenitude of mystical experience, which is the Arhat state.

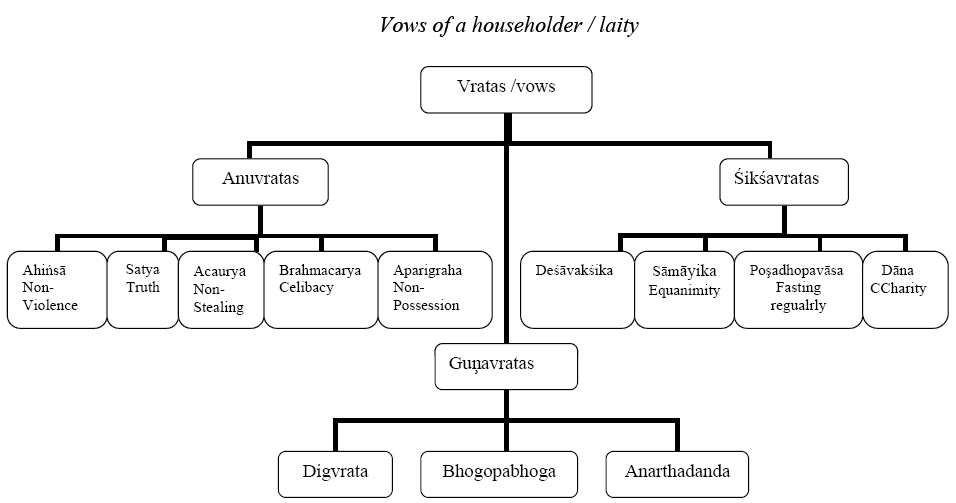

Thus the householder and the ascetic are the two wheels on which the cart of Jaina ethical discipline moves on quite smoothly. It is to the credit of Jaina ācāryas that they have always kept in mind these two orders while prescribing any discipline to be observed. They were never in favour of confounding the obligations of the one with the other. In consequence, Jainism could develop the ācāra of the householder with as much clarity as it developed the ācāra of the Muni. Being overwhelmed by the ascetic tendency, it has not neglected the ācāra of the householder. By developing the doctrine of Aṇūvratas, Gūṇavratas and Śikṣāvratas for the householder it has shown the way in which the householder should direct his course of life. I feel that the doctrine of Aṇūvratas, Gūṇavratas and Śikṣāvratas is the unique contribution of Jainism to Indian ethics.

2.1 Nature of Ethico-Spiritual Conduc

Let us now proceed to deal with the nature of ethico-spiritual conduct, which transforms the potential excellences of the self into actuality. With the light of value knowledge, which enables the aspirant to look into his infirmities, the pursuit of ethico-spiritual conduct sweeps away the elements, which thwart the manifestation of uninterrupted happiness and infinite knowledge. Value knowledge illumines the path and ethico-spiritual conduct leads to the goal. In addition to spiritual awakening and value- knowledge emancipation presupposes ethico-spiritual conduct as well. Really speaking, ethico-spiritual conduct emanates from the internal necessity, which the spiritually awakened has developed in him. Thereby he then expunges the disharmony existent between his present and future conditions, and between his potential conviction and actual living.

So important is the pursuit of ethico-spiritual conduct for realising the transcendental nature of self that Kundakunda calls it Dharma.[8] Such conduct as will conduce to the emergence of a state of self which is devoid of infatuation (Moha) and perturbation (Kṣobha) by virtue of the subversion of all kinds of passions in their most comprehensive extent is called Vītarāga Cāritra. This should be distinguished from Sarāga Cāritra’ which results in auspicious activities by virtue of auspicious psychical states.

The auspicious activities are no doubt the part of ethico-spiritual conduct; but the inauspicious activities emanating from inauspicious psychical states are in no way be the part of conduct, hence they are to be completely relinquished. Thus, in order to stamp out the inauspicious psychical states from the texture of self, the aspirant must abstain himself root and branch from violence, falsehood, theft, un-chastity and acquisition. The engrossment of the self into such vicious deeds is indicative of the expression of the most intense passions, which can be wiped off by negating to perform the vicious deeds.

The negative process of purifying the self by weeding out these villainous actions of necessity requires the pursuance of the positive process of non-violence, truthfulness, non-thieving, chastity and non-acquisition. Both of these processes keep pace together. The elimination of these vices requires the cultivation of virtues of non-violence, truthfulness, non-thieving, chastity and non-acquisition. Of these virtues, non-violence is the fundamental. All the rest should be regarded as the means for its proper sustenance, just as the field of corn requires adequate fencing for its protection. The householder can partially acquire these virtues, which are then called partial non-violence (Ahiṅsā-Aṇūvrata), partial truthfulness (Satya-Aṇūvrata), partial non-thieving (Acaurya-Aṇūvrata), partial chastity (Brahmacarya-Aṇūvrata) and partial non-acquisition (Parigraha-parimāṇa-Aṇūvrata).

2.1.1 Spiritual Awakening, Inauspicious Activities and Morality

We cannot forbear mentioning in passing that even a spiritually awakened person may be occupied with the aforementioned evil deeds; the recognition of which would at the first sight tend to annul the distinction between the wise and the ignorant, or between the spiritually awakened and perverted souls. But this assumption is based on a certain misapprehension. Notwithstanding their extrinsic similitude they evince intrinsic disparity; i.e., the wise under some latent constraint unwillingly perpetrate such evil actions, and the ignorant while rejoicing commit them. From this it is obvious that spiritual awakening is not incompatible with the most intense forms of inauspicious activities. It will not be inconsistent if it is laid down that both the wise and the ignorant are capable of extirpating inauspicious psychical states. But the difference is that while in the former case there is spiritual morality, in the latter, there is only dry morality, which is possible without spirituality. Dry morality is socially useful, but spiritually barren; while spiritual morality is fruitful both socially and spiritually. Being subtle and far-reaching, the internal distinction between these two types of morality eludes our limited comprehension. We may simply say that, for the spiritually awakened, morality is a means; while for the perverted it is an end in itself. It is to be borne in mind that morality, of whatever type, can in no case be useless; hence it deserves our respect wherever it is witnessed.

2.1.2 Vikala-Cāritra (Partial Conduct) and Sakala Cāritra (Complete Conduct)

It astonishes that in spite of not being the part of conduct in any way, the aforementioned vicious deeds refuse to be completely relinquished at the start on account of their being ingrained in the mind of man. Hence, there arises the concept of limited morality technically called Vikala Cāritra (partial conduct) in contrast to absolute morality known as Sakala Cāritra (complete conduct) wherein these vicious deeds are completely renounced. He who observes the former, being not able to renounce the vices to the full, claims the title of a layman; while he who observes the latter, being able to hold the spirit of renunciation to the brim, is called a Muni'.

2.1.3 Meaning of the Commitment of Hiṅsā

For explaining Vikala Cāritra (partial conduct), and Sakala Cā¢ritra (complete conduct) let us be clear about the meaning of Hiṅsā. The term Hiṅsā may be defined as the committing of injury to the Dravya-prāṇas and the Bhāva-prāṇas through the operation of intense passion infected Yoga[9] (activity of mind, body, and speech). Suicide, homicide and killing of any other life whatsoever aptly sum up the nature of Hiṅsā, inasmuch as these villainous actions are rendered conceivable only when the Dravya-prāṇas and the Bhāva-prāṇas pertaining to oneself and to others are injured. The minimum number of Dravya-prāṇas has been considered to be four, and the maximum has been known to be ten; and the Bhāva-prāṇas are the very attributes of Jīva. The amount of injury will thus be commensurate with the number of Prāṇas injured at a particular time and occasion. If the bodily movements etc., are performed with circumspection, nevertheless if any living being is oppressed, it cannot be called Hiṅsā for the infecting element of intense passion is missing.[10] On the contrary, even if, by careless bodily movements no animate being is oppressed, the actions are not free from Hiṅsā. Here though the soul has not injured others, yet it has injured itself by defiling its own natural constitution.[11] We may thus say that both the indulgence in Hiṅsā and the negation of abstinence from Hiṅsā constitute if, by careless bodily movements no animate being is oppressed, the actions are not free from Hiṅsā. [12] In other words, he who has not abandoned Hiṅsā though he is not factually indulging in it, commits Hiṅsā on account of having the subconscious frame of mind for its perpetration. Again, he who employs his mind, body and speech in injuring others also commits Hiṅsā on account of actually indulging in it. Thus, wherever there is inadvertence of mind, body or speech, Hiṅsā is inevitable. [13]

2.1.4 Internal Mind and Outward Action

It will be the height of folly and impertinence if any man conceitedly argues that it is no use renouncing the performance of certain actions, but that the internal mind alone ought to be uncontaminated. But it is to be borne in mind that in lower stages, which exceedingly fall short of self-realisation, the external performance of a man has no meaning without his being internally disposed to do so. Hence the external and the internal influence each other; and in most cases the internal precedes the external. Thus, in no case, the outward commission of Hiṅsā, without the presence of internal corruption can be vindicated. He who exclusively emphasizes the internal at the expense of the external forgets the significance of outward behaviour.[14] He loses sight of the fact that the impiousness of external actions necessarily leads to the pollution of the internal mind, thus disfiguring both the aspects, namely, the internal and the external. In consequence, both the Niścaya and Vyavahāra Nayas, i.e., both the internal and external aspects should occupy their due places.

2.1.5 Intentional and Non-Intentional Hiṅsā

Hiṅsā is of two kinds, namely, intentional and non-intentional.[15] The intentional perpetrator of Hiṅsā engages himself in the commitment of the acts of Hiṅsā by his own mind, speech and action; provokes others to commit them; and endorses such acts of others. Besides, Hiṅsā, which is unavoidably committed by defending oneself from one’s foes, is denominated as non-intentional defensive Hiṅsā. This leads us to the philosophy of fighting defensive wars.[16]

2.1.6 Ahiṅsā (Aṇūvrata - Mahāvrata)

The householder, being snared in the meshes of infirmities, is incapable of turning away completely from Hiṅsā, hence he should keep himself away from the deliberate commission of Hiṅsā of the two-sensed to five-sensed beings.[17] The commitment of Hiṅsā in being engaged in a certain profession, in performing domestic activities and in adopting defensive contrivances, cannot be counteracted by him. Thus he commits intentional injury to one-sensed Jīvas, namely, the vegetable-bodied, the air-bodied, the fire-bodied, etc.; and non-intentional injury in performing ārambha (domestic activities), Udyoga (profession) and Virodha (defense). He can therefore observe the gross form of Ahiṅsā, which is known as Ahiṅsā Aṇūvrata. Even in the realm of one-sensed Jīvas and in the realm of non-intentional injury he should so manage to confine his operations as may affect the life and existence of a very limited number of Jīvas.[18] In these two provinces the point to note is that of alleviating the amount of injury that is apt to be caused and not that of total relinquishment which is not possible without jeopardizing the survival of man. Nevertheless, Hiṅsā even in the realm of one-sensed Jīvas and in the realm of non-intentional injury is unjustifiable. If we reflect a little, we shall find that man is subject to Hiṅsā by the very condition of his existence. Yet instead of aggravating the natural weight of Hiṅsā by falling foul upon one another and by our cruel treatment of the animal and vegetable kingdoms, we should endeavour to alleviate this general curse, to the extent to which we are capable of doing, by conforming ourselves to the sacred injunctions enjoined by Jaina spiritual teachers. The observer of Ahiṅsā Aṇūvrata should avoid gambling, hunting, drinking, meat eating, and the like. Vegetarianism is therefore prescribed. It limits us to the unavoidable injury caused to only one-sensed-Jīvas. This is the philosophy of vegetarianism propounded by Jainism.

The Muni extends active friendship to all living beings from the one-sensed to the five-sensed without any exception, and consequently all forms of intentional Hiṅsā are shunned and the question of being engaged in a certain profession, in performing domestic activities and in adopting defensive contrivances does not arise in his case. Thus the Muni follows Ahiṅsā Mahāvrata. The Muni is a world citizen. He, therefore, draws the attention of men to the inefficacy of Hiṅsā for solving social, national and international disputes. He himself is the embodiment of Ahiṅsā and exhorts others to develop reverence for life as such.

2.2 Satya (Aṇūvrata - Mahāvrata)

It implies the making of wrong and improper statement by one who is overwhelmed by passions such as anger, greed, conceit, deceit and the like. Falsehood is of four kinds. [19] The first kind of falsehood refers to the affirmation of the existent as non-existent[20], the second refers to the declaration of the non-existent, as existent[21] the third refers to the representation of the existing nature of things as different from what they are[22], and the fourth is indicative of speech which is disagreeable to others[23]. The Muni avoids all these four forms of falsehood, and therefore, he is said to observe Satya Mahāvrata. But the householder has to speak harsh, unpleasant, violent words for defence, for running the household and doing professional management, therefore, he observes Satya Aṇūvrata. The observer of Satya Aṇūvrata- does use words, which are soothing, gentle and ennobling. If any speech causes Hiṅsā, it should be withheld. Ultimately the criterion of Satya and Asatya is Ahiṅsā and Hiṅsā respectively. Thus Satya speech should lead to Ahiṅsā.

2.3 Asteya (Aṇūvrata - Mahāvrata)

Steya means the taking of things under the constraint of passions without their being given by the owner[24]. It may be noted here that things constitute the external Prāṇas of a man and he who thieves and plunders them is said to deprive a man of his Prāṇas [25]. This is not other than Hiṅsā. The Muni who observes Mahāvrata does not take anything whatsoever without the permission of others, but the householder uses such things freely as are of common use without their being given, such as well water, and the like[26]. Thus he is observing Asteya Aṇūvrata. It may be noted here that the Muni does not use even the common things without their being given by others. The householder does neither take those things which are forgotten and dropped by others nor give them to any one else[27]. Purchasing of costly things at reduced prices is stealing, which is probably due to the fact that one may sell a thing after getting it by improper methods[28]. Adulteration, abetment of theft, receiving stolen property, use of false weights and measures, smuggling, and the like are considered as part of stealing.

2.4 Bṛahmacarya (Aṇūvrata - Mahāvrata)

Sex-passion is Abṛhma. He who frees himself completely from sexual inclination is observing Bṛhmacarya Mahāvrata. However, householder, who abstains himself from the sexual contacts with all other women except his nuptial partner, is observing Bṛahamcarya Aṇūvrata [29]. Sex-passion is Hiṅsā and Bṛahamcarya is Ahiṅsā The householder keeps himself away from adultery, prostitution, unnatural methods of sexual enjoyment and the like. [30]

2.5 Aparigraha (Aṇūvrata - Mahāvrata)

Attachment to things is Parigraha. [31] Those who have a feeling of attachment to things in spite of their external renunciation are far from Aparigraha and those who have external things are not free from internal attachment. [32] Thus if one is prone to remove internal attachment, one should correspondingly throw aside external possessions also. Attachment is a form of Hiṅsā and those who wish to practice Ahiṅsā should avoid attachment. The householder is incapable of renouncing all Parigraha, therefore, he should limit the Parigraha of wealth, cattle, corn, buildings etc. [33] This is Parigraha Parimāṇāuvrata. The Muni renounces all Parigraha of worldly things. Thus he follows Aparigraha Mahāvrata.

Parigraha-Parimāṇāuvrata is socially very important. We should bear in mind that economic inequality and the hoarding of essential commodities very much disturb social life and living. These acts lead to the exploitation and enslavement of man. Owing to this, life in society is endangered. Consequently, Jainism pronounced that the remedy for the ill of economic inequality is Parigraha Parimāṇāuvrata. The method of Parigraha Parimāṇāuvrata tells us that one should keep with one self that which is necessary for one's living and the rest should be returned to society for its well being. Limit of wealth and essential commodities are indispensable for the development of healthy social life. In a way wealth is the basis of our social structure and if its flow is obstructed because of its accumulation in few hands, large segments of society will remain undeveloped. The hoarding of essential commodities creates a situation of social scarcity, which perils social life. In order to resist such inhuman tendency, Jainism incessantly endeavoured to establish the social value of Parigraha Parimāṇāuvrata.

Apart from the Aṇūvratas, the śrāvaka (the householder) has to observe the three Gūṇavratas and four Śikṣāvratas known as seven Śīlavratas. These Śīlavratas serve the useful purpose of guarding the Aṇūvratas.. They effect a positive improvement in the observance of Aṇūvratas. That which refrains unlimited movement in any direction is Digvrata; that which refrains from going to some region is Deśavrata. That which refrains wanton activity is Anarthadaṅavrata. All these three are styled as Gūṇavratas (vows of withdrawal).

3.1 Nature of Digvrata

It consists in fixing the limits of one's own movements in the ten directions. [34] For the purpose of demarcation are utilised the well-known signs, such as oceans, rivers, forests, mountains, countries and yojana stones. [35] As regards the time limit, Samantabhadra[36] and Akalanka[37 ]explicitly prescribe its life-long observance, while the other ācāryas implicitly state so. The śrāvaka Prajñapti[38] tells us that since the householder is like a heated iron ball, his movements, wherever they are made, entail Hiṅsā. If the area of his movements is circumscribed, he will thereby save himself from committing Hiṅsā as such outside that area. Thus by the avoidance of even the subtle sins beyond the determined limits, the Aṇūvratī (householder) becomes like a Mahāvratī (ascetic) in respect of the regions lying beyond those limits. [39] Besides, the Kārttikeyanuprekṣā, tells us that by fixing the limits in all the ten directions the passion of greed is controlled. [40] This may be explained by saying that the Digvratī has automatically renounced the getting of wealth, even if it can be easily got, from the area outside the limits.[41] It will not be idle to point out here that the limitation of movements in the external world tends to reduce the internal passions, thereby fulfilling the purpose for which the Digvrata is enjoined.

3.2 Nature of Deśavrata

The Sarvārthasiddhi expound the nature of Deśavrata as limiting one's own movements to the region determined by certain villages and as renouncing the rest of the places.[42] Vasunandi has explained it by affirming that it implies the abandonment of the habitation of those countries or places where the observance of vows is threatened or rendered difficult.[43] It is very interesting to note that Śrutasāgara, the 16th century commentator of the Tattvārthasūtra has subscribed to the view of Vasunandi by saying that the Deśavrata consists in discarding those places which obstruct the due observance of vratas and which occasion insalubrity’s mind.[44]

3.3Nature of Anarthadandavrata

Kārttikeya defines Anarthadandavrata as renouncing the commitment of such acts as is not subservient to any useful purpose.[45] Being frivolous, they simply engender insalubrity’s mind, which results in depravity. The śrāvaka Prajñapti affirms that actions without any purpose bring about more Karmic bondage than the actions with some end in view, inasmuch as the former may be committed at any time even without any necessity, while the latter are performed at some specific time out of some necessity.[46]

3.3.1 Forms of Anarthadandavrata

The perpetration of barren and inane actions admits of multitudinous forms, but for the sake of comprehension five forms have been recorded. Kārttikeya, Samantabhadra, and the commentators of Tattvārthasūtra like Pūjyapāda and Akalaṅka, recognise five forms of Anarthadandas. They are:

- Apadhyāna,

- Pāpopadeśa,

- Pramādacarita,

- Hiṅsādāna

- Duśruti

Firstly, Apadhyāna implies inauspicious reflections, which procreate nothing except a vicious trend of thought. This involves the fact of peeping into another man's faults and infirmities, coveting another man's wealth, seeing another man's wife with an evil eye,[47] witnessing the dissension among persons[48], mutilating, imprisoning and killing others and getting interested in hunting, victory, defeat, war, adultery, theft, gambling and the like.[49]

Secondly, Pāpopadeśa means the giving of evil instructions to persons earning livelihood by service, business, writing documents, cultivating land and working in the field of art.[50] Samantabhadra, Pūjyapāda, Akalaṅka include in Pāpopadeśa the following things: the talk of selling slaves and beasts profitably and the giving of direction to hunters, fowlers and the like. [51] Thus the provocation of vicious tendencies on account of which an individual may indulge in corrupted, passionate, and life-injuring ways may briefly sum up the meaning of Pāpopadeśa.

Thirdly, Pramādacarita consists in doing such actions purposelessly as digging the ground, uprooting trees, trampling lawns, sprinkling water, burning and quenching fire, plucking leaves, fruits and flowers, wandering[52] etc.

Fourthly, Hiṅsādāna implies the giving of the instruments of Hiṅsādāna like knife, poison, fire, sword, bow, chain etc to others. [53] According to Kārttikeya the rearing of violent animals like cats etc., and the business of weapons like iron etc. come under Hiṅsā.[54]

Lastly, Duśruti, implies the listening to and teaching of such stories as are passion exciting. Besides, the study of literature aggravating worldly attachment, describing erotic things, and dealing with other intensepassion exciting things has also been included in Duśruti.[55]

Keeping limited things of use (Bhogopabhogapramāṇavrata); pursuing self-meditation (Sāmāyikavrata); observing fast in a specific way (Proṣadhopavāsavrata) and offering food etc. (Atithisaṅvibhāgavrata) to a non-householder guest who observes self-restraint and propagates ethico-spiritual values- all these four have been proclaimed to be Śikṣāvrata (vows of pursuance).

3.4 Nature of Bhogopabhogapramāṇavrata

We now proceed to deal with the nature of Bhogopabhogapramāṇavrata. The word Bhoga' pertains to those objects which are capable of being used only once, for instance, betel-leaf, garland, etc., and the word Upabhoga' covers those objects which are capable of being used again and again, for instance, clothes, ornaments, cots,[56] etc. Thus the Bhogopabhogapramāṇavrata implies the limitation in the use of the objects of Bhoga and Upabhoga in order to reduce attachment to the objects.[57] It may be pointed out here that this Vrata includes not only the positive process of limitation, but also the negative process of renunciation. Kārttikeya tells us that the renunciation of those things that are within one's own reach is more commendable than the renunciation of those things that are neither possessed, nor likely to be possessed in future. Samantabhadra points out that the Vrata does not consist in giving up things unsuitable to oneself along with those which are not worthy to be used by the exalted persons, but that it consists in the deliberate renouncement of the suitable objects of senses, since the above two types of things are not even used by commonplace persons.[58] Amṛtacandra tells us that the layman should renounce, according to his capacity, the use of objects which are not prohibited.[59]

3.5 Nature of Sāmāyika

Sāmāyika is the positive way of submerging the activities of mind, body and speech in the Ātman.[60] The consideration of seven requisites is necessary for the successful performance of Sāmāyika.[61]

1

Place

2

Time

3

Posture

4

Meditation

5

Threefold purities, namely:

mental 6 bodily 7 vocal

3.6 Nature of Proṣadhopavāsavrata

Samantabhadra[69] and others, enunciate[70] the Proṣadhopavāsavrata as ‘renouncing the four kinds of food on the eighth and fourteenth lunar days in each fortnight’. Probably keeping in view the infirmness of disciples, Kārttikeyanuprekṣā [71] also includes the eating of unseasoned food once a day in the Proṣadhopavāsavrata, and Amitagati[72] and Āśādhara[73] also comprise the taking of only water in this Vrata. The observance of this Vrata requires the performance of meditation, the study of spiritual literature, and the avoidance of bath, perfumes, bodily embellishment, ornaments, cohabitation and household affairs. [74] The śrāvaka Prajñapti prescribes that the relinquishment of food, bodily embellishment, cohabitation; household affairs should be affected either partially or completely in the Proṣadhopavāsavrata. As regards the place for the performance of this Vrata, a temple, the abode of Sādhus, a Proṣadhopavāsavrata or any holy place should be chosen for one's stay.[75]

3.7 Nature of Atithisaṅvibhāgavrata

He who offers four kinds of gifts to deserving recipients is pursuing the Atithisaṅvibhāgavrata.[76] Four kinds of gifts have been recognised; namely, food, medicine, books and fearlessness.[77] Food, medicine, Upakaraṇa (religious accessories) and the place of shelter is the other list of four objects.[78] All these things should be worthy of the Pātras. Only such things should be given as are useful for the pursuance of studies and for practicing austerities of a very high quality, and as do not bring about attachment, aversion, incontinence, pride, sorrow, fear and the like.[79] Just as water washes away blood, so proper gifts to saints would for certain wipe off the sins accumulated on account of the unavoidable household affairs.[80] The paying of obeisance to the holy saints causes noble birth; the giving of Dāna to them entails prosperous living; their servitude promotes high respect; their devotion determines gracious look; and the extolling of their virtues brings about celebrity. [81] Vasunandi tells us that the gift to Pātras is just like a seed sown in a fertile land; the gift to Kupātras is just like a seed sown in a semi-fertile land; and the gift to Apātras is just like a seed sown in a barren land. [82]

4.1 Eleven Pratimās: (Eleven Stages for Becoming Excellent śrāvaka)

The eleven Pratimās are denominated

- Darśana,

- Vrata,

- Sāmāyika,

- Proṣadha,

- Sacittatyāga,

- Rātribhuktityāga,

- Bṛhmacarya,

- Ārambhatyāga,

- Parigrahatyāga,

- Anumatityāga,

- Uddiṣŧatyāga. 83

Darśana Pratimā: The fist stage is Darśana Pratimā. After the attainment of Samyagdarśana the aspirant who should be styled Dārśanika śrāvaka resolutely forsakes the use of odious things such as meat, wine and the like, and becomes indifferent to worldly and heavenly pleasures, and nourishes the spirit of detachment. If we subtract the attainment of Samyagdarśana from this stage we shall get the eleven stages of moral advancement in contradistinction to the eleven stages of spiritual advancement owing to Samyagdarśana.

Vrata Pratimā: The second stage is called Vrata Pratimā. This second rung of the ladder of the householder’s evolution of conduct comprises the scrupulous observance of Aṇūvratas, Gūṇavratas and Śikṣāvratas. We have already dwelt upon the nature of these vratas, so need not turn to them again.

Sāmāyika and Proṣadha Pratimās: The third and fourth stages bear the designations of Sāmāyika and Proṣadha Pratimās respectively. A question may be asked: when Sāmāyika and Proṣadha Pratimās have been treated as Aṇūvrata, why have they been regarded as constituting the third and fourth Pratimās, respectively? As a matter of fact, these sum up the entire spiritual life of the householder. Besides, Sāmāyika, and Proṣadhopavāsa are closely interrelated and so influence each other. Proṣadhopavāsa assists in the due performance of Sāmāyika and sometimes Sāmāyika encourages the performance of the other with purity and zeal. In the science of spirituality theory cannot countervail practice. So, if these two Vratas are elevated to the rank of Pratimās, it is to favour the deepening of spiritual consciousness, and hence it is justifiable.

The remaining Pratimās: All the subsequent stages rest on the relinquishment of Bhoga and Upabhoga. Sacittatyāga Pratimā consists in renouncing the use of articles having life, namely, roots, fruits, leaves, barks, seeds and the like. The observer of the discipline prescribed by this stage does not also feed others with those things, which he himself has renounced. The next stage is recognised to be Rātri Bhuktivirati. This stage refers to the object of Bhoga predominantly food. He who has ascended this stage neither eats food nor feeds others at night. The next stage known to as Brahmacarya Pratimā prescribes absolute continence. This is indicative of the further limitation in the objects of Upabhoga. The eighth stage of householder’s advancement, which is known as ārambhatyāga signifies the discontinuance of service, cultivation, and business, in short, the means of livelihood. Besides, he neither suggests others to do business, etc., nor commends those who are doing so. The next stage, namely, Parigrahatyāga Pratimā enjoins the abandonment of all kinds of acquisitions except clothes, and in those too the observer is not attached. In the tenth stage, the aspirant refuses to give advice or suggestion regarding matters concerning the householder, hence it is called Anumatityāga Pratimā Here all the objects of Bhoga and Upabhoga have been renounced except clothes, and proper food cooked for him. The highest point of householder’s discipline is arrived at in the eleventh stage when the aspirant renounces home and goes to the forest where ascetics dwell and accepts vows in the presence of a Guru. He performs austerities, lives on food obtained by begging, and wears a piece of loincloth. Thus he is designated as excellent śrāvaka and the stage is called Uddiṣŧatyāga Pratimā.

Transgressions / Flaws of Vows

- Non-violence

- Binding living beings in captivity

- Beating living beings

- Mutilating limbs

- Overloading excessive weight on living beings

- Withdrawing or providing insufficient food or water to living beings.

- Truth

- Untruth pertaining to ownership

- Forgery or adulteration of goods

- Misrepresentation as witness

- Divulging secrets of others

- Using harsh language

- Non-Stealing

- Pick up goods not given and employing thieves to obtain things

- Receiving stolen merchants

- Using false weights and measures

- Adulterating commodities

- Accepting goods without paying or underpaying the required taxes and price

- Celibacy

- Company of prostitutes or other women

- Arranging marriages of others children

- Perverted sexual practices or Use other parts of body for sexual satisfaction

- Use sexually provocative language

- Excessive craving for the company of other sex

- Non-Possession

- Gaining new lands

- Disguising excess accumulation of gold and silver

- Going beyond the volume limit on grain/foodstuffs by repackaging these commodities in more compact containers

- Not counting on newborn of the livestock as an increase in overall holdings, since they were “not purchased”

- “Diminishing” the amount of household goods by combining them, welding plates together.

- Digvrata Vow for Directional Movements

- Ignorantly going in upward direction

- Ignorantly going in downward direction

- Ignorantly going in linear direction

- Increase the location limits

- Transgress the limited space in ignorance

- Bhogopbhoga or Limit Use or Desire of Things used once (Food) and many times (Clothes etc).

- Reminiscing the things consumed earlier

- Excess indulgence in too much action (vulgar) before others.

- Excessive craving for consumption of things in future

- Passions and attachment in the present things

- Flaws of anarthadanda (useless or without purpose Activities)

- Brooding

- Purposeless mischief

- Facilitation of destruction

- Giving harmful advice

- Helping hunters to find animals

- Flaws of Deśāvakāśika (Movement Restrictions of Cities, Countries etc.)

- Ask others to do work exceeding his limits without transgressing ones own

- Do the with some other sound like coughing

- Ask others to get things

- Expose oneself to others

- To throw stones etc on others

- Flaws of Sāmāyika (Equanimity or Concentration)

- Unclear expression of words or mantras

- Constant movement of ones body

- Mentally engaging in other thoughts than on spirituality

- Thinking that Sāmayika is useless

- Forget the Mantras or Sutras during Sāmayika because of unstable mind

- Flaws of Poşadhopavāsa or fasting regularly

- Dying with hunger he wears the clothes of Puja

- Due to above he also does urine in negligence

- Due to hunger in negligence he puts the bed

- Due to hunger in negligence he does not do any work with respect

- Due to hunger in negligence his mind remains unstable

- Flaws of Dānā or Charity

- Cover food with leaves

- Put food on the leaves

- Disrespect while giving

- Careless while giving

- Is unhappy when others are giving

Pravacanasāra of Kundakunda with the Commentaries of Amṛtacandra and Jayasena, I.7, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa).

Puruṣārthasidhyupāya of Amṛtacandra, 75, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa).75; Cāritra Pāhuda of Kundakunda, 24, (Pātanī Digambara Jaina Granthamālā Māroha under the title " Aṣŧa Pāhuda); Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, 155, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi).53; Puruṣārthasidhyupāya of Amṛtacandra, 77 (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa); Vasunandi śravakācāra, 209, (Bhāratīya Jñāna Pītha, New Delhi). Yoga Śāstra of Hemacandra II. 21, (Prākṛta Bhāratī Academy, Jaipur).

Vasunandi śravakācāra, 212; Yaśastilaka and Indian Culture by Handiqui, Page 267 (Jīvarāja Granthamālā, Sholapur).

Puruṣārthasidhyupāya of Amṛtacandra, 124 to 128, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa).

Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi)., 61;

Kārttikeyanuprekṣā, 340, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa).

Kārttikeyanuprekṣā, 342, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa)., Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi).,, 68; Yogasāstra, III. 1.

Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi).69; Puruṣārthasidhyupāya of Amṛtacandra, 137, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa).

Sarvārthasiddhi, VII. 21.

Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, 155, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi).70; Puruṣārthasidhyupāya of Amṛtacandra, 138, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa)., Sarvārthasiddhi, VII. 21.

Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, 155, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi).78; Sarvārthasiddhi, VII. 21.

Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, 155, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi)., 76; Sarvārthasiddhi, VII. 21.

Kārttikeyanuprekṣā, 346, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa). 6; Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra, 80; Sarvārthasiddhi, VII. 21; Puruṣārthasidhyupāya of Amṛtacandra, 143, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa).

Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, 155, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi)., 77; śravakācāra Prajñapti, Comm. 289; Puruṣārthasidhyupāya of Amṛtacandra, 144, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa)., Sāgāradharmāmṛta of Āśādhara, V. 8 (Bhāratīya Jñāna Pītha, New Delhi.

Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, 155, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi)., 79; Kārttikeyanuprekṣā, 348, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa; Sāgāradharmāmṛta of Āśādhara, V.9.

Kārttikeyanuprekṣā, 350, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa). Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, 155, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi).82; Sarvārthasiddhi, VII. 21; Sāgāradharmāmṛta of Āśādhara,V 13.

Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, 155, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi)., 86, Kārttikeyanuprekṣā, 351, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa).

Puruṣārthasidhyupāya of Amṛtacandra, 151, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa). Sāgāradharmāmṛta of Āśādhara, V. 34; Kārttikeyanuprekṣā, 359, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa).; Yaśastilaka and Indian Culture, Page 282.

Kārttikeyanuprekṣā, 362, (Rājacandra Āśrama, Āgāsa). Amitagati śravakācāra, IX. 83, 106, 107; Vasunandi śravakācāra, 233.

Ratnakaraṅdaśravakācāra of Samantabhadra, 117, (Vīra Sevā Mandira, Delhi). Yaśastilaka and Indian Culture, Page 283.