1

Jaina Art as Potent Source of Indian History, Culture and Art

(With Special Reference to the Kuṣāṇa Images From Mathurā)

Kuṣāṇa Period: Mathurā (The Period of Beginning and Standardization)Art is the living visual account of our tradition, including the concept in religion and philosophy that prevail during an epoch in society. And yet, while discussing history or religion, philosophy and culture, we tend to take into account only literature as the main narrative along with inscriptions and coins and miss out the artistic creations of temples, stūpa, sculptures and paintings, or the other forms of art embodying the spirit of the time.

Jainism is a living religion with innumerable followers in India as well as abroad. It developed as an independent religious and cultural stream contributing greatly to the life and mind of the Indian people. The very fact of the emergence of Jainism under certain socio-religious conditions could be seen in its denial of the Vedic socio-religious order. Jainism was older than Buddhism, being historically established at least 250 years before the origin of Buddhism.

In the Jaina context, art has been the main vehicle for the wide and dynamic expression of Jaina spirituality, the absolute renunciation of all possessiveness, and the ideals of non-violence and austerity, besides providing the information about the patronage of ruling dynasties, and traders and mercantile classes. The Jaina sculptures also reveal the forms and features of dress, ornaments, hair style and attributes which are important and direct source for the reconstruction of the cultural history of any period and region.

The poetics of the Jaina concepts, woven into the attitudes, gestures and postures of the images, brought forth multiple layers of meanings in visual language. The subject chosen was depicted in the human form - whether legend, deity or sage. However, the person was revered for the ideal quality epitomized. The inspirational quality of a Jina, highest in Jaina worship, was his invincibility as the soul of perfection. Other qualities and state of being worthy of worship were: the vitarāgī (free from desire and passion); nirgrantha (free from knots of bondage of Karma); the posture kāyotsarga (standing erect in the attitude of dismissing the body); dhyāna-mudrā (seated cross-legged in deep meditation); and finally the aparigraha (non-possession) and tyāga (renunciation). Of course, the subject most often chosen by the artist to project the wholeness of his inspiration was one of the 24 Jinas. The other main legendary subjects were - Bāhubali, the personification of endurance, non-violence and non-acquisition (aparigraha) and Bharata Muni, the prince who is worshipped not as Chakravartin or emperor, but as Muni after renouncing the material world and taking the path of absolute renunciation. Besides these, there were also the images and paintings depicting ascetics and holy mendicants - ācāryas, sādhus and sādhvīs. The subject of art always remained close to the popular imagination and art sought to enhance it with the artistic experience, taking great care to acknowledge the perfection of the ideals projected. Through all such renderings ideal social models were provided.

There are inscriptional evidences from Mathurā (Kaṅkālī Ṭīlā), Osiāñ, Delvāḍā, Khajurāho, Kumbhāriyā, Jalor, Śravaṇabeḷgola and several other places which frequently refer to the traders and merchant community who were making significant contributions towards the development of Jainism and thereby Jaina art.

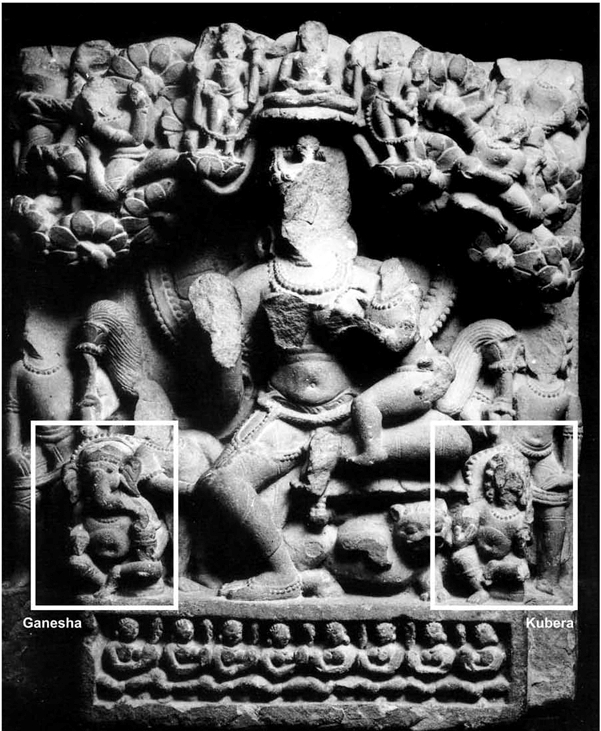

The Jainas never hesitated in borrowing what was suitable for Jainism to make it more accessible for the masses. They established balance between the spiritual and material world for the worshippers through representing the figures of Tīrthaṅkaras and yakṣas-yakṣīs together in one icon format (Harivaṃśa Purāṇa, 783 A.D.). The Jainas also assimilated several Brahmanical deities and represented them in art with grace and honour. In the process, Neminātha was depicted with Balarāma and Kṛṣṇa in Kuṣāṇa and sculptures of subsequent period. The figures of Rāma, Brahmā, Viṣṇu, Śiva, Kāma, Balarāma, etc., along with their respective śaktis were depicted on the exterior wall of the Pārśvanātha Jaina temple at Khajurāho, while those of Gaṇeśa at Mathurā (Archaeological Museum, Mathurā - pedestal of Ambikā image) and Kumbhāriyā (basement of Neminātha temple, 12th cent. A.D.). Notably, the earliest known figure of goddess Sarasvatī in Indian art hails from Mathurā and belongs to the Jaina tradition. The pedestal inscription gives the name of Sarasvatī and is dated to year 54 of Kuṣāṇa rule (=132 A.D.). This image was carved by the donation of lohikakarukasya-dānam (ironsmith) Gova for the welfare and happiness of all (sarvvasatvānām hitasukhā).

The Jaina images from Mathurā, belonging to Kuṣāṇa period, bear several inscriptions on pedestals which show that all classes of Kuṣāṇa society were contributing to the carving of Jaina images. From the Kuṣāṇa inscriptions from Mathurā[1] it also appears that foreign population including women enthusiastically took part in Jaina art activity. Another peculiarity of Mathurā Jaina inscriptions is that the majority of donors have been female worshippers. Even in subsequent centuries we find that women as queens, wives of traders and merchants and as lay devotees contributed immensely to the development of Jainism and Jaina art. This could be because the principles of Jainism, specially non-violence, were suitable more to the temperament of women. Some of the names of women of Indian origin in Kuṣāṇa inscriptions are- Kṣudrā, Mitrā, Sucilā, Bodhinandi, Dattā Siṃhadattā, Gulhā, Balahastini, Śivamitrā, Amohini, Dharmaghoṣā, Śivayaśā, Mitaśri, Jitamitra, Acalā. On the other hand names like Akka, Oghā, Okharikā, Ujhaṭikā appear to be of foreign origin. Apparently the liberal Jaina social concept of equality without disparity of cast or class encouraged the business class and foreign people to embrace Jainism and contribute to its development by different means. This remained the socio-economic feature of subsequent period also. The inscriptions inscribed on pedestals of independent and four-fold (Pratimā-Sarvatobhadrikā) Tīrthaṅkara images including Sarasvatī image of 132 A.D. of Kuṣāṇa period from Mathurā reveal the universal concept of the Welfare and Happiness for All (Mankind).[2] The Jainas did have forceful impact on the contemporary ruling class also because they were having hold on the economy because of their active involvement in trade and commerce.

The Plates:Jainism thrived vigorously during the Kuṣāṇa period, but without any direct royal patronage of the Kuṣāṇa rulers. This is why we do not find any Jina figure on the Kuṣāṇa coins as well as in the art remains from their nucleus political domain of Gandhāra region. But the variety of iconographic forms in the Kusana Jaina images and their profuseness must have been because of the existing well organised Jaina organisation at Mathurā and also strong support and patronage which in this case was from the masses as is evident from the Kuṣāṇa inscriptions.

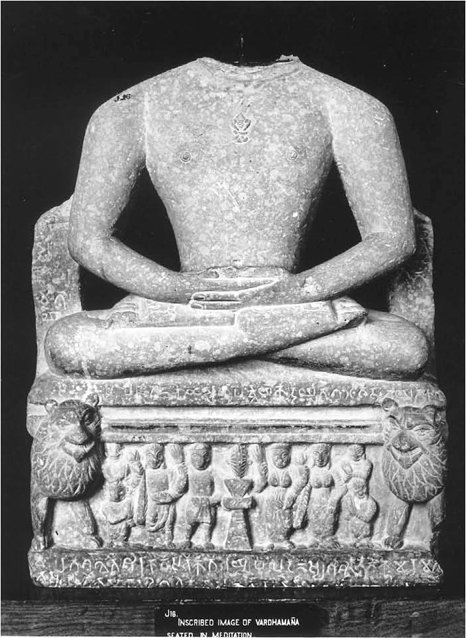

The geographical environment and also the situation of Mathurā on the commercial route greatly helped in making the city a great centre of art, including Jaina art. The numerous Kuṣāṇa Jaina inscriptions from Mathurā referring to the donation made by śreṣṭhin, sārthavāha, gāndhika, suvarṇakāra, vardhakin, lauhakarmak, nartaka, prātārika (nāvika), veśyās, cotton dealers and different goṣṭhīs (traders community) towards the installation of Jaina images, at once suggest that the people following different crafts and occupations actively contributed to the development of Jaina art. Most of the inscriptions have dates, mostly in Śaka era, which are very important from the view point of the reconstruction of Kuṣāṇa history and culture as a whole. These inscriptions also provide the exact identifications and dates in cases of the images of Sarasvatī (Sarasvato– Śaka era 54 = 132 A.D.), Ṛṣabhanātha (Vṛṣabho or Usabho- Śaka era 46 = 124 A.D.), Śāntinātha (Śaka era 19 = 97 A.D.), Ariṣṭanemi (Śaka era 18 = 96 A.D.), Pārśvanātha (Pārśva) and Mahāvira (Vardhamāna- Śaka era 5 = 83 A.D., 22 = 100 A.D., 29 = 107 A.D., 42 = 120 A.D., 50 = 128 A.D.) and Jina Caumukhī images (Pratimāsarvatobhadrikā, Śaka era 18 = 96 A.D., 32 = 110 A.D.) and Ayāgapaṭa (Āyāgapaṭo). These inscriptions invariably give the word ‘Arhat’ for the Jinas, which show that Arhat was the earliest adjective used for the Jinas and the words Jina and Tīrthaṅkara came only subsequently.

The concept and visual forms both of Jina and Buddha crystallized in Kuṣāṇa images reveal points of commonality. The assimilation of the features of yogī (meditative posture and half-shut eyes), mahāpuruṣa (long arms, ears and halo) and cakravartin (lion throne, fly-whisk bearing attendants) into the iconic forms of both the Jina and Buddha reveal cultural synthesis and commonality.

Although Mathurā yielded a few examples of Śuṅga period mainly in the form of āyāgapaṭas, yet as a prolific and formative centre of Jaina art it flourished only during the Kuṣāṇa age[3] (1st-2nd cent. A.D.). The excavations at Kaṅkālī Ṭīlā, Mathurā, yielded a vast amount of Jaina vestiges ranging in date from c. 100 B.C. to 1177 A.D. The Kuṣāṇa Jaina sculptures from Mathurā are of special iconographic significance since they exhibit a formative stage in the development of Jaina images, which served as models for further development throughout the subsequent centuries. The vast amount of Jaina images includes, besides the āyāgapaṭas, independent Jina figures, Pratimā-sarvatobhadrikā (Jina Caumukhī), Sarasvatī, Naigameṣī and also the narrative scenes from the lives of Ṛṣbhanātha and Mahāvīra.

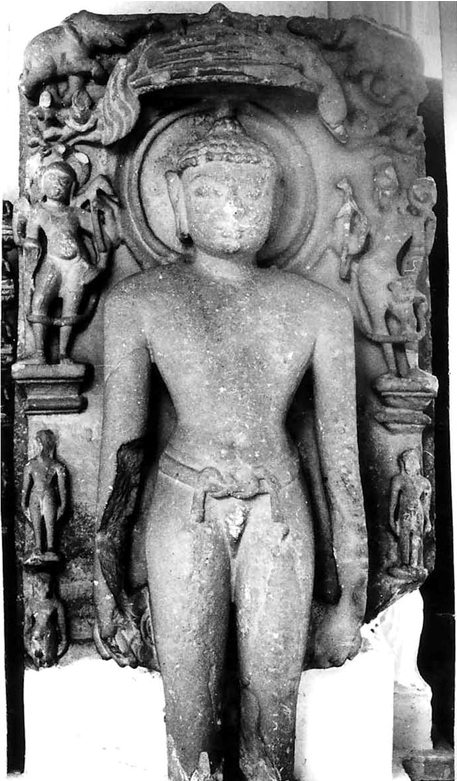

The Jina figures of Kuṣāṇa art may be divided into four contexts: the āyāgapaṭas, independent figures, Jina Caumukhī and the slab with narratives from the lives of the Jinas. The figures on the āyāgapaṭas are always seated in the dhyāna-mudrā, while those on the Caumukhī are invariably standing in the kāyotsarga-mudrā. The Jinas, either standing or sitting, do not show any trace of drapery, which, however, fully conform to the Āgamic tradition. Some of the scholars, however, hold that the nudity of the Kuṣāṇa Jina figures from Mathurā is suggestive of their being the product of the Digambara sect but the presence exclusively of Śvetāmbara theme and feature in two cases: narrative panel showing the transfer of embryo of Mahāvīra (State Museum, Lucknow, J. 626) and a slab showing the figure of Kaṇha Śramaṇa (State Museum, Lucknow, J. 623) with a piece of cloth hanging from his folded wrist to cover his genitals, poses a puzzling question as to their exact sectarian affiliation.

We would like here to mention that the Ācāraṅga-sūtra (c. 2nd century B.C.) frequently refers to both the acelaka (sky-clad) and sacelaka (draped) ways of living for Jaina friars. The Uttarādhyayana-sūtra (c. 2nd century B.C.) also mentions the acelaka and sacelaka ways for the Jaina munis as per need of situation. As we know, the authority of the Āgama texts, belonging to the Śvetāmbara and hence of the Yāpanīya sect, has not been accepted by the Digambara sect, according to which the original Aṅga texts were lost. Thus the Kuṣāṇa Jina images from Mathurā, showing full concurrence with the Āgamic tradition can suggest no sectarian affiliation with the Digambaras. It rather, and up to at least the mid-second century A.D., represents the undifferentiated proto-Śvetāmbara and Digambara sects. The earliest examples showing distinctly the difference of the Śvetāmbara and the Digambara sects in visual representations are known only from the late fifth century A.D. onwards (as exemplified by Akoṭā Jaina bronze images from Gujarat).

In the gamut of Kuṣāṇa sculptures the rendering of auspicious symbols (svastika, śrīvatsa, triratna, cakra or dharmacakra, pūrṇaghaṭa, mīnayugala) was also very popular. Besides rendering of auspicious symbols either in group of eight (aṣṭamangala) or separately as svastika, dharmacakra, stūpa on āyāgapaṭas, these are carved also on the snake hoods covering the head of Pārśvanātha (svastika, dharmacakra, triratna, śrīvatsa) and on the soles, palms and finger-tips of different Jina figures (svastika, cakra, triratna). However, as far as these auspicious symbols and their renderings are concerned they should be taken as non-sectarian in character since they were derived from the common ancient Indian heritage mostly of Vedic tradition. Such symbols could be identified as Jaina or Buddhist only in reference to their representational context. Aṣṭamaṅgala-mālā (garland with eight auspicious marks) and triratna (three jewels of Buddhism and Jainism), cakra (disc or wheel of religion or disc) and śrīvatsa are commonly found in Buddhist (Sāñchī, Bharhut, Takshashila) and Jaina (Mathurā) art and literature (Aṅgavijjā - Jaina text) to denote cultural commonality.

Ṛṣabhanātha with lateral strands, name and bull cognizance has semblance with Śiva, while Neminātha joined by the figures of Balarāma and Vāsudeva Kṛṣṇa and endowed in Gupta period with conch cognizance reveal bearing of Vaiṣṇava or Bhāgavata cult. Pārśvanātha with a seven-hooded snake canopy overhead has distinct impact of Nāga cult for which Mathurā was so well known[4]. The Paumacariyaṃ of Vimalasūri (1st to 4th cent. A.D.) eulogizes Ṛṣabhanātha with appellations such as Brahmā, Trilocana, Śaṅkara and Ananta Nārāyaṇa (5.122). Further Ṛṣabhanātha, in the Ādipurāṇaof Jinasena (8th century A.D.), has been endowed with 1008 appellations which distinctly show the cordial and interactive approach of Jainism in assimilating Brahmanical and Buddhist deities such as Svayambhū, Śambhū, Śaṅkara, Sadyojāta, Trinetra, Jitamanmatha, Tripurāri, Trilocana, Śiva, Īśāna, Bhūtanātha, Mṛtuñjaya, Maheśvara, Mahādeva, Jagannātha, Lakṣmīpati, Dhātā, Brahmā, Hiraṇyagarbha, Viśvamūrti, Vidhātā, Buddha, Pitāmaha, Caturānana, Indra, Mahendra, Sūrya, Āditya, Kubera, Vāmanadeva, Rāma,Kṛṣṇa and Buddha (Ādipurāṇa 25.100-217).

An āyāgapaṭa (now in State Museum, Lucknow, J.623) bearing an inscription dated 99 (possibly of Śaka era = 177 A.D.) is particularly interesting because it shows at its top a stūpa in the centre flanked by two Jina figures on each side[5]. All the Jina figures are seated cross-legged in meditation. Of the four Jinas, one on the left of stūpa having a seven-hooded snake canopy overhead is undoubtedly Pārśvanātha. Even in the absence of the cognizances or any other distinctive identifying features, the Jinas may be identified (from left to right) as Ṛṣabhanātha, Neminātha (stūpa in the centre) and Pārśvanātha and Mahāvīra. The identification goes well in order especially in view of the texts namely Kalpasūtra (1st to 3rd century A.D.) and also the Rūpamaṇḍana (15th century A.D.) wherein the above four Jinas are said to have been the most favoured ones. The paṭa is also suggestive of the worship of the symbol (stūpa) and human form (Jina) together. Below this small horizontal panel are carved two other main figures occupying major space on the slab. Of the two standing male and female figures, one is of an ascetic who is shown covering his genital part with a piece of cloth (ardhaphālaka-sacelaka, i.e. Śvetāmbara?) in hand. He also holds a broom (rajoharaṇa) in the right hand. The figure is labelled in the inscription as Kaṇha Śramaṇa identifiable with Vāsudeva Kṛṣṇa shown as an ascetic. The early Jaina texts like Antagaḍadasāo refer to Kṛṣṇa as Kaṇha Vāsudeva and also mention that he took dīkṣā (initiation). Apparently the figure of Kaṇha Śramaṇa is Kṛṣṇa as an ascetic. Close to Kṛṣṇa stands on his left a male figure with folded hands and with seven-hooded snake canopy. He could be identified as Balarāma, the elder brother of Kṛṣṇa. On the right of Kaṇha there appear two-armed female goddesses, whose right hand is in abhaya-mudrā and who is labelled in the inscription as Anaghaśreṣṭhividyā. The goddess represents Vidyādevī, popular in Jaina worship. The name suggests her popularity in business community.

The figures of Neminātha, also called Ariṣṭanemi in some pedestal inscriptions from Mathurā (birthplace of Bhāgavata cult), are accompanied by the figures of his cousins, Balarāma and Vāsudeva- Kṛṣṇa. The association of Balarāma and Kṛṣṇa with Neminātha was in agreement with the Jaina tradition. The prominence of the Bhāgavata cult in Mathurā was also an inspiring force for this association. This assimilation is ratified also by the early Jaina works of 2nd-1st century B.C. to 2nd century A.D. namely Uttarādhyayana sūtra (22nd chapter titled Rathanemi), Nāyādhammakahāo (68) and Antagaḍadasāo. Subsequently works like Harivaṃśa Purāṇa (of Jinasena, 783 A.D.), Uttarapurāṇa (of Guṇabhadra, 9th cent. A.D.) and Triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacarita (of Hemacandra, c. 1150 A.D.) also mention this association at length.

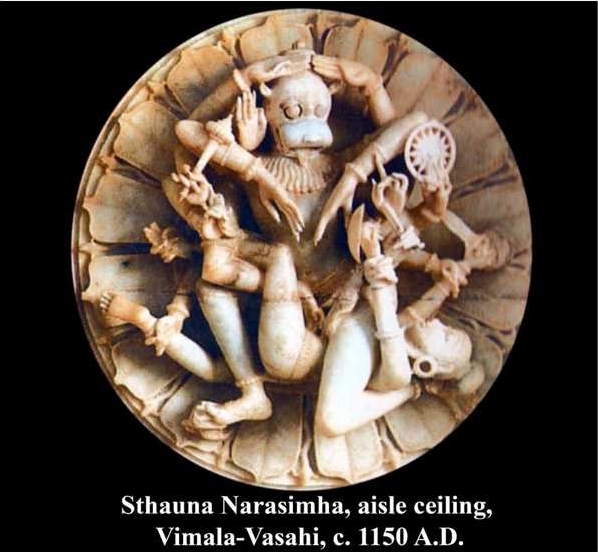

The Neminātha figures accompanied by Balarāma and Vāsudeva-Kṛṣṇa are quite interesting since they suggest syncretic concept and also mutuality in Jaina worship as early as in the Kuṣāṇa period. In one instance of c. 1st century A.D. (State Museum, Lucknow, J. 37), the seated figure of Neminātha is joined by the figures of four-armed Balarāma and Vāsudeva- Kṛṣṇa on the right and left sides respectively. Balarāma holds a pestle (mūsala), a plough (hala) and a wine-cup (pāna-pātra) in three of his surviving hands while Kṛṣṇa, wearing a vanamālā, shows abhaya-mudrā and a mace. However, the other two figures of Neminātha, seated as he is in dhyāna-mudrā, also contain such figures but here a two-armed Balarāma is shown in namaskāra-mudrā with a canopy of a seven-hooded cobra. Another Neminātha image of late Kuṣāṇa period exhibits the figures of four-armed Balarāma with ploughand Kṛṣṇa with mace and disc in their surviving hands (Government Museum, Mathurā, Acc. No. 2502). There are five other Jina images wherein two flanking male figures, one with a snake canopy, the other with crown and both shown with folded hands are carved (State Museum, Lucknow, J.4, J.60, J.117; Government Museum, Mathurā, B.15, 34.2488). These flanking figures have rightly been identified by N.P. Joshi as Balarāma and Kṛṣṇa and hence the Jina, on this strength, as Neminātha[6]. Such sculptural examples to some extent are also indicative of the superiority of Jina Neminātha over the Vaiṣṇavite deities. The Vaiṣṇava impact further blossoms during medieval period (9th to 13th century A.D.) and Neminātha images with flanking figures of four-armed Balarāma and Vāsudeva Kṛṣṇa are found from Mathurā and Deogarh, besides several Vaiṣṇava themes like Kāliya-mardana, Kṛṣṇa playing Holī (sprinkling of coloured water on gopa-gopikās) and his birth and childhood episodes carved in Jaina temples of Delvāḍā (Vimala-Vasahī and Lūṇa-Vasahī, 12th- 13th century A.D.).

Another significant form of Kuṣāṇa Jina image was a four-fold image, known as Pratimā-Sarvatobhadrikā or Jina Caumukhī, about 20 examples of which are found at Mathurā. The terms “Pratimā-sarvatobhadrikā” and “Sarvatobhadra pratimā” mentioned in pedestal inscriptions denote that the image was auspicious from all the sides.[7] The carving of Jina Caumukhī, showing four Jina figures standing on four sides, started as early as in the first century A.D. and its earliest examples are procured from Kaṅkālī Ṭīlā, Mathurā. Such images remained popular in all the regions in subsequent centuries and further developed as Sarvatobhadra-Jinālaya (temple), the examples of which are at Guna (M.P.), Kharatara-Vasahī (Delvāḍā) and Rāṇakpur (Rajasthan). The temples were built during 11th - 12th to 15th centuries A.D.. Culturally expressions like sarvatobhadra or sarvajana hitāya sukhāya in the Jaina images of Kuṣāṇa period present the mindset of Jainas in particular and the very purpose of Indian art as a whole.

Scholars generally believe that the conception of Jina Caumukhī was based on the early conception of Jina Samavasaraṇa with advancement upon it.[8] But this view is not acceptable for the following reasons. The Samavasaraṇa is the congregation hall erected by the gods where from every Jina delivers his first sermon after attaining kevala-jñāna (omniscience). It consists of three circular ramparts at the top of which sits the Jina (seated), facing east. The three other figures of the selfsame Jina on the remaining three sides were installed by the Vyantara gods to facilitate audience worshippers to have the look (darshan) of the Jina from all the sides. However, none of the early Jaina works like Kalpasūtra and the Paumacariyaṃ refer to the installation of Jina images on the remaining three sides. Its first mention occurs only in the works of eighth-ninth century A.D.[9] Moreover in the Kuṣāṇa Caumukhī images four different Jinas, always standing, are carved on four sides, as against the original conception of Samavasaraṇa of having a seated Jina on the top (facing east) along with three figures of the selfsame Jina on the remaining three sides.

Thus it would not be appropriate to conclude that the Jina caumukhī of the Kuṣāṇa period, showing four different Jinas on four sides, bears any impact of the conception of the Samavasaraṇa. It is rather difficult to find any traditional basis for the conception of the Jina Caumukhī fromthe Jaina works. On the other hand, we come across a number of such sculptures in contemporary and even earlier Indian art which might have inspired the Jainas to carve Jina Caumukhī. It is not impossible that some such representations as the Sārnāth and Sāñchī lion-capitals and multi-faced yakṣa[10] figure and svastika[11] may have been the source of inspiration.

We are also tempted to call these Jina Caumukhī figures, showing four different Jinas, equal in status on four sides, a form of composite (saṃghāṭa) icon, which thus marked the beginning of the rendering of syncretic image in Jaina context.

The above study reveals that Jaina images, besides their art (iconographic and aesthetic) value, could be the potent source of the reconstruction of contemporary political, social and cultural history. And their in-depth study in this context should now be encouraged.

Plate 1.1

Plate 1.2

Plate 1.3

Plate 1.4

Plate 1.5

Plate 1.6

Plate 1.7

Plate 1.8

Plate 1.9

Plate 1.10

G. Bühler, “Further Jaina Inscriptions from Mathurā”, Epigraphia Indica, Vol. II, Delhi, 1983 (Rep.), pp. 198-212.

Maruti Nandan Pd. Tiwari, Elements of Jaina Iconography, Varanasi, 1983, pp. 1-10; “Prayāg Maṇḍala mein Jaina Dharma aur Kalā”, Prayag Kshetriya Itihāsa Visheshāṅk (Bhāratīya Itihāsa Sankalan Samiti Patrikā), (Edits.) Dr. S N Roy etc., No. 2, Varanasi, 1984, pp. 210-215; U.P. Shah, 'Beginnings of Jaina Iconography', Bulletin of Museums and Archaeology in U.P., No. 9, June 1972, pp. 3-6.

G. Bühler, 'Specimens of Jaina Sculptures from Mathurā', Epigraphia Indica, Vol-II, pp. 311-22; U.P. Shah, “Evolution of Jaina Iconography and Symbolism”, Aspects of Jaina Art and Architecture, (Eds.) U.P. Shah and M.A. Dhaky, Ahmedabad, 1975, pp. 49-74; V.S. Agrawala, 'Some Brahmanical Deities in Jaina Religious Art', Jaina Antiquary, Vol. III, No. IV, March 1938, p. 59; V.A. Smith, The Jaina Stupa and other Antiquities of Mathurā, Varanasi (reprint), 1969, pp. 56-57.

Debala Mitra, “Mathurā”, Jaina Art and Architecture, (ed. A. Ghosh), Vol. I, p. 57; M.N.P. Tiwari, Jaina Pratimāvijñāna, Varanasi, 1981, p. 47.

N.P. Joshi, “Early Icon from Mathurā”, The Cultural Heritage, (Ed.) D.M. Srinivasan, New Delhi, 1989, pp. 335-38.

Epigraphica Indica, Vol-II, pp. 202-03, 210, Inscription Nos. 2, 13, 16; B.C. Bhattacharya, The Jaina Iconography, Lahore, 1939, p. 48.

U.P. Shah, Studies in Jaina Art, Varanasi, 1955, pp. 94-95; De, Sudhin, 'Caumukha a Symbolic Jaina Art', Jain Journal, Vol. VI, No. I, 1971, p. 27.

Dr. Shanti Swaroop Sinha

Dr. Shanti Swaroop Sinha

Prof. Dr. Maruti Nandan P. Tiwari

Prof. Dr. Maruti Nandan P. Tiwari