The poor seeking wealth, only wreck their peace;

The rich, wealth-inflamed, are no less bewildered!

The causes of unrest are: "Too much / Too little."

He alone knows joy who is evenly poised.

Man is ever restless. Why? Is it because his needs are not being fulfilled? Or because his desires go on increasing? How is it that the whole and invisible power of consciousness becomes subservient to a divided and unintegrated mental disposition?

The basic needs of life, the utility thereof, cannot be denied, because those needs are natural. Religion does not aim at the elimination of natural needs; rather it aims at underlining the distinction between need and desire. Generally, a man is not conscious of it. He substitutes desire for need and works hard for its fulfilment. But it is an established truth that need can be fulfilled, but the pit of desire can never be filled. The difference between need and desire is very clear. Yet these are so intermingled that a common man finds it difficult to draw a dividing line between them. That a man should be concerned about fulfilling the minimum requirements of life, is natural. But it is surprising that even after his needs are fulfilled, with a great deal of money piled before him, man continues to be dissatisfied. That dearth should produce unrest is logical, but that excess of material possessions should also be accompanied by disturbance, is not so intelligible. It has been observed that a man suffering from want is not so unquiet as the man who is rolling in plenty. From all this, at least one, fact stands out: that the lack of material things may produce disquietude, but the possession of material goods by itself is no guarantee of complete satisfaction. If material goods could guarantee peace, then prosperous people possessed of all kinds of material comforts, should never.have known disquiet. The sight of well-to-do people caught in fright, suffocation, despair and dissatisfaction supports the belief that the factor of mental peace is neither dearth nor abundance, but an equanimous mind.

In a state of scarcity, many anxieties arise and therefore the mind is disturbed. But in a state of excess, too, there may come thoughts of fear, uncertainty and madness. As compared to scarcity, excess breeds more worries. The root of unquiet is the web of uncertainties. The fewer the options, the lesser is the turmoil. That man should engage himself in activity to the limit of fulfilling his needs, is perfectly in order. But when he spends most of his time in unnecessary pursuits, he is certainly inviting disquietude.

A coolie worked every day in accordance with his need. He earned only as much as he needed and thus lived without any care. One day, he was able to earn the usual amount by midday. So he sat in quiet, without a thought. At that very moment a businessman called him for carrying a pitcher full of oil. The coolie refused since he had already earned enough for the day. The businessman wanted to reach home urgently and no other coolie was available at that time. So, he offered a temptation by saying, "Come, lift the pitcher. I'll give you a rupee." (A rupee in those days had ten times its present value). The mention of a rupee made the coolie's eyes gleam. He lifted the pitcher on his head, and followed the businessman.

As he went along the coolie said to himself "Today I shall be earning one rupee extra. What am I going to do with it? Why not buy a hen? The hen would lay eggs. I'll sell the eggs and earn more money. Later I might as well buy a goat. The goat. would yield milk and also calves. I would sell the whole lot and buy a cow. The cow, too, would breed many calves. By disposing them of, I should have a lot of more money. This would enable me to buy a mare. I would then start some small business. As my business prospers, I would become quite famous. Now I would lack no money. I would get a building constructed in this very city. I might as well marry and beget children." The coolie got so absorbed in his stream of thought, that every imaginary picture appeared to him to be real. Now he imagined himself sitting and working in his office situated in the outer part of his building. Inside the house there was a great hustle and bustle; the children were making merry. Then the children suddenly entered his office to call him for lunch. Even though they called twice or thrice, he did not respond and kept busy with his work. At last his wife herself entered his office to say, "The food is getting cold, please come at once!" He lifted his face a little and nodded his head and said, "No. Not yet." The lifting and nodding of the head made him lose his balance and the pitcher of oil fell down to the ground, and was broken into smithereens. All the oil was spilled. The businessman started scolding him, "You fool! How you walk! You have laid waste oil worth 10 rupees:" At this, the coolie weepingly said, "Sir, you have only suffered a loss of ten rupees, but my whole career is destroyed!" The businessman started in wonder, "What's that? How is your future destroyed?" And the coolie told him of his plan even as he wept bitterly.

The above story makes it abundantly clear how the network of thought creates sorrow. To the extent that a man is free from thoughts, he may experience joy and peace.

You say that both want and excess make for unrest, and that equanimity alone leads to tranquillity. What is the nature of this equanimity?

Equanimity may be defined in different ways. However in the present context, by equanimity is meant ‘control over memory and restrained imagination'. Useless memories and wild imagination can only be productive of sorrow. Since they are not related to his needs, they cause a lot of trouble to man. Memory and imagination are caused by conflict in the mind, because man is caught in conflicting desires. As long as man abides wholly in himself, he is not tormented by any memory or imagination. Profit and loss, joy and sorrow, life and death, praise and blame, flattery and insult - in the context of these opposites, the doctrine of imagination control assumes great significance. Whether in profit or in loss a man is assailed by imaginary concepts. But a fact, an actual occurrence, is not an idea; it is simply a fact. It is only when memory and imagination operate upon the fact that concepts arise. This truth is also confirmed by another observation: if material goods could remove man’s fear, the rich people and the public leaders would never experience anguish, as also brought out in a couplet in Preksha Sangan:

If power, wealth, prosperity could terror dissolve,

The chieftains and the rich would never suffer despair!The more wealthy a man is, the more eminent a leader, the greater is their frustration. Affluence and power cannot remove their fright. What to speak of dissolving their fear, these eminent men cannot even enjoy good sleep. What an irony of fate!

Without taking pills they cannot sleep!

These poor rich-folk with darken'd consciousness!Many people take pills so as to be able to sleep. Not to speak of common people, even those who take pride in being called sadhaks and boast of undertaking high austerities and penance, take recourse to intoxicating drugs to achieve mental peace. Look at the irony of common people seeking guidance from them for learning the technique of awareness, while these so-called spirltualists, instead of undertaking proper tapasya, befuddle their wits with intoxicants.

Liquor, hemp and other intoxicants lust-provoking.

They take regularly, and derive from it some comfort;

During the hangover they feel utterly let down,

Sorely afflicted; with peace, strength, memory, all gone!Such people, in order to achieve mental peace, or freedom from worry or sheer self-forgetfulness, consume various kinds of intoxicating drugs. They derive some satisfaction, but it is momentary. As the intoxication wears off, their restlessness increases a thousandfold. This results in the weakening of nerves and further excitation. To restlessness is now added an acute feeling of loss of strength and memory, and the individual feels totally disintegrated. In fact, disintegration is the inevitable accompaniment of destitution or excess. Only an equanimous mind can save one from such disintegration. For the practice of equanimity, the control of memory and thought is absolutely necessary.

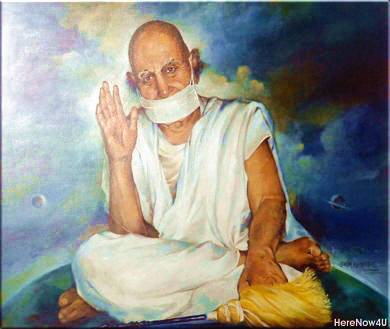

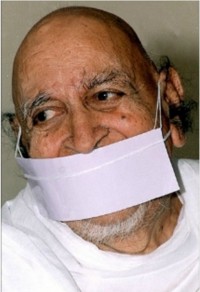

Acharya Tulsi

Acharya Tulsi