Asceticism and, in particular, the radical renunciation practised in Jainism, symbolises the principles of spiritual striving and dependence upon the self alone to achieve the ultimate objective of liberation. Jain asceticism has a multi-dimensional character: it is personal, religious and social in nature. Despite the fact that it is primarily concerned with personal spiritual progress, one cannot deny its social role in religious teaching, sermons, motivating the laity, and protecting the integrity of the fourfold order.

Before discussing the orders of ascetics in Jainism, let us briefly consider comparable orders in other religions. Hindus, Buddhists and Christians have monks and nuns, either based in 'religious houses' or 'wandering', from early in their histories. But in general there have been two ways in which Jain ascetics differed from those of other religions. The first is in the degree of renunciation by Jain ascetics, which has always been radical. The second difference is that Jain ascetics do not separate themselves from the community as happens in some Christian 'closed orders', for example, the Carthusians. Some religions, for e.g. Islam, Judaism and Sikhism, do not possess monastic orders.

In Hinduism men (generally women would not do this) pass through the four stages of life: 'studentship' (brahmacaaryaasram), 'householdership' (grahasthaasram), 'forest-dwelling' (vanaprasthaasram) and 'renunciation' (sanyaasaasram). When family responsibilities are completed, usually about the age of fifty, one retires to the forest to lead a life of detachment in pursuit of spiritual progress, and when the aspiring ascetic is ready for renunciation, he becomes a sanyaasi. However, some aspirants become ascetics (sanyaasis) in adulthood without completing their 'household duties'. Hindu ascetics have many orders and hierarchies; they wear reddish-yellow or saffron robes and live in monasteries run by individuals or public institutions. In contrast to Jain ascetics, they may use transport; wandering and begging alms are not their norms and most of them will accept donations of money. Rough estimates put the figure of Hindu sanyaasis and related ritualists at several millions (5.2 million according hearsay), but forest dwelling sanyaasis are a rarity today.

The Buddhists have about a million ascetics, called bhiksus. There are a number of Buddhist nuns, but their numbers and importance have always been marginal. Ascetics wear yellow robes and live for the most part in monasteries, although they may wander and may beg alms; usually they are vegetarian, but they may eat non-vegetarian food if it is not especially cooked for them but perchance given to them as a donation. After an initiation ceremony, they are trained to follow strict rules of conduct. One can be a Buddhist ascetic for a short period, in contrast to the Jain vow of renunciation, which is of a permanent nature. Though there are seniors and juniors among Buddhist ascetics, the authority is collective. A monk may leave the order, and expulsion is possible for transgressions of the rules of conduct, but the Buddhist monastic order is not as disciplined as the Jain ascetic order.

There are many orders of Christian monks and nuns, and the following is a general impression: Initiation involves undertaking the three vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, and by adopting the way of life of Christian orders, monks and nuns are supposedly imitating the life of Jesus Christ. Members of orders are celibate and may live among the community or separated in monasteries and nunneries. The majority of Christian clergy, who today include women as well as men, are not monks and nuns. Many monks and nuns serve the community in charitable work, in caring for the sick and in teaching. The process of becoming a member of a religious order involves passing through stages, usually spending a period as a novice, before full acceptance. Monasteries and nunneries are organised under the authority of a monk or nun. While in the Middle Ages, in Europe, the religious orders wielded great influence as centres of literacy, culture, and economic and political power; the modern age has seen their influence decline sharply.

Jainism believes that over a time the physical and psychic strengths of human beings have been gradually decreasing and, as a result, one of two possible forms of asceticism, the 'Jina-model' (jinakalpi), is a rarity, and the other form, the 'order-model', is the norm today.

There is a hierarchy of Jain ascetics, regulated by the sangha, where the head of an order is an aacaarya. Where there are many aacaaryas, a supreme head (gacchaadhipati or ganaadhipati) may be chosen, but this is a modern development. Below the level of the aacaarya there are those who act as teachers to the other ascetics, the 'preceptors' (gani, panyaasa, or upadhyaaya) and the lowest member in the hierarchy is the ordinary ascetic (muni or saadhu).

Aacaarya: The aacaarya is the spiritual leader of the sangha, who pursues the path of liberation as expounded by the tirthankara. He acquires this position through his spiritual and intellectual attainment and his potential to maintain and strengthen the order. Seniority alone has never been the sole criterion for becoming an aacaarya. The aacaarya observes five principles relating to knowledge (jnaanaacaar), faith (darsanaacaar), conduct (caritraacaar), austerity (tapaacaar), and spiritual energy (viryaacaar). Ideally an aacaarya will fulfil thirty-six attributes:

- five controls over the senses;

- nine restraints for the observance of celibacy;

- four restraints of the passions;

- five great vows;

- five observances (detailed above);

- five carefulness in walking, speaking, eating, picking and placing, and 'bodily functions'; three guards of thought, speech and action (Doshi C. 1979: pp 8-11).

Upaadhyaaya: The upaadhyaayas are experts on the scriptures. They study and teach them to other ascetics. They are required to possess 25 attributes made up of proficiency in the 11 texts of the primary canon, 12 secondary and have Right faith and Right conduct.

Saadhus or munis: An ordinary ascetic strives to possess 27 (or 28) qualities, which are listed later in this chapter.

Qualifications and Restrictions for Asceticism: Jainism believes that spirituality is a fundamental human characteristic, thus there are virtually no restrictions on initiation to the asceticism; those restrictions which are applied relate to the candidate's potential to fulfil the requirements of the vocation, for example, to travel, to learn, to teach. Many prominent aacaaryas came from non-Jain backgrounds. The only restrictions upon initiation are: candidates should not be below eight years of age; should not be infirm due to their age; should not be deaf, dumb, blind or crippled; should not be mentally disabled; should not be of a current criminal disposition (reformed candidates are acceptable); and may be disqualified through certain statuses e.g. debtors, slaves, eunuchs, kidnapped, etc. Women candidates who are pregnant or nursing young children are not accepted.

Initiation as ascetics: When a candidate decides upon initiation, the spiritual head assesses their suitability and, if suitable, requires them to obtain permission from their parents or guardians. If permission is refused or cannot be obtained for practical reasons, the spiritual head re-examines the resolve of the candidates and if then satisfied, initiates them into the order.

The initiation ceremony (diksaa) takes place in the presence of the sangha, where the spiritual head administers the vow of equanimity (saamayika) throughout life, and the vow to discard all sinful activities. Before entering the order, candidates are given a new name to signal the break with the past worldly life. After initiation, the novice ascetic begins training by undertaking austerities in respect of the ethical code of ascetics, and the protection of living beings, including one sense beings, and is taught to study the scriptures. Novice ascetics are also encouraged by seniors to observe fasts and other austerities for increasing spiritual energy. After due initiation and training, the spiritual head confirms the novice ascetic into the order in the presence of the sangha by administering the threefold vow: 'I will not commit sins with body, mind or speech; I will not see them committed and I will not encourage or appreciate such sins'.

Ascetics occasionally breach the rules of conduct. Twenty-one such transgressions are mentioned in the scriptures, and the expiation or atonement texts (Cheda Sutras) prescribe minor and major penance for these transgressions. An ascetic must perform penance and in the event of severe breaches may lose a period of seniority, as he or she is regarded as having lapsed from membership of the order. In extreme cases they may be expelled and, if this happens, reinitiation is the only remedy.

Basic Virtues of an Ascetic: Jain texts describe 27 basic virtues or attributes for ascetics to achieve physical control and spiritual advancement, with minor differences between the Svetambar and Digambar traditions, and it is expected that every ascetic will observe and practise these virtues. The virtues are as follows (numbers indicate how the figure of 27 is arrived at):

Five: major vows of 'non-violence', truthfulness, 'non-stealing', celibacy, and 'nonattachment'.

Six: 'protections' of living beings: five categories of 'one-sense' beings, and the sixth of mobile beings; Jains believe that there are minute living beings of earth, water, air, fire, and vegetable life.

- Five: controls over the five senses.

- Three: disciplines of mind, speech and body.

- One: forgiveness.

- One: control over greed.

- One: inner purity.

- One: observances of five types of carefulness, three types of safeguards, sleep, renunciation of non-religious anecdotes and control over indiscretion.

- One: prohibition of eating at night.

- One: carefulness in cleaning belongings to avoid harm to living beings.

- One: endurance of afflictions.

- One: forbearance, even in mortal disasters (Vijaydevasura Sangh 1981: p.70)

Svetambar ascetics wear white unstitched cloth, but have no attachment to them. Digambar ascetics discard all clothes and are 'sky-clad'. Svetambar ascetics sleep on the ground or on a wooden board, resembling a low table. Digambar ascetics sleep on dried grass. There are differences between the traditions in the way ascetics accept food from devotees: Digambar ascetics eat at devotees' homes once a day in the standing posture, following the example of Mahavira. Svetambar ascetics accept appropriate simple food that is not prepared for them from more than one home of a devotee, and share it in the upashraya with fellow ascetics. The acceptance of food is termed as gocari ('grazing') for which strict rules are laid down (aacaaranga: 1990: 2.9. 390-405). They remind themselves that food is only to sustain the body. They do not eat at night and drink only boiled water.

Ascetics walk barefoot; do not use vehicles; do not accept, possess or hoard money; and stay in one place only for a short time, on average a maximum of five days, except during the four months of the monsoon, when they do not travel. They preach the teachings of Mahavira to the laity during their stay, do not remove their hair with razors or scissors, but pluck it with their fingers. The aim of all these practices is to strengthen observance of the ascetic virtues and detachment from the body.

The worldly conduct of ascetics: There are two types of conduct as described for ascetics (Uttaraadhyayana Sutra): worldly conduct and spiritual or vow-related conduct. The ten rules of conduct are prescribed for inculcating humility and respect for others, especially senior ascetics. They are:

- Seeking approval of actions.

- Asking other ascetics if they require food or other necessities.

- Showing food collected as alms to the senior ascetic or guru.

- Inviting other ascetics to share food.

- Asking the pardon of the senior ascetic or guru, using the phrase 'may my faults be forgiven.

- Asking permission from the senior ascetic or guru for work, or to leave the upashraya or residency.

- Saying 'that is so' (tahatti) to the teacher's sermons and instructions.

- Seeking permission before acquiring 'religious riches' i.e. studying scriptures, performing austerities and other spiritual practices.

- Saying the words 'may I go out' (avassahi) while going out of temples or upashrayas.

- Saying the words 'may I come in' (nissahi) while coming into temples or upashrayas (Uttaraadhyayana Sutra 1991: 1.1-44).

Ascetics share belongings: bedding, food, scriptures, pupils, and provide services to seniors and to infirm ascetics.

The spiritual ethics of the ascetics: The second type of conduct is represented by vow-related or ethical conduct. The whole life of an ascetic is directed towards conduct leading to the stoppage of karmic influx and the shedding of accumulated karma. This conduct is described in chapter 4.1. Ascetics scrupulously follow the rules relating to food. They will prefer to fast rather than take inappropriate food. These rules are meant to strengthen the morality of non-violence and detachment. When accepting food ascetics must be careful about a number of factors: (1) the type and preparation of food by the laity; (2) the attitude of the laity offering food; (3). the ascetics' own attitude towards the food. The Aacaaranga Sutra (1990: vol.2 chapter 1) and Dasavaikalika Sutra (1993: chapter 5) describe twenty-six 'defects' in the first factor, sixteen 'defects' in the second

and four 'defects' in the third.

The daily routine of ascetics: The Uttaradhyayana Sutra (1991: chapter 36) gives details of the daily routine of ascetics. The 24 hours are divided into eight segments, four each for day and night and for convenience, we describe the general daily routine observed by ascetics, which may vary according to circumstances.

| 04.00 | rise in the holy morning (brahma muhurta); |

| 04.0005.30 | silent recital of the Namokar Mantra, self-introspection and meditation; |

| 05.3006.00 | service to the senior ascetics and aacaaryas; |

| 06.0007.00 | daily 'natural duties;' |

| 07.0008.00 | self-study and penitential retreat |

| 08.0009.00 | careful cleaning of pots, begging for water, food and alms (Svetambar); |

| 09.0010.00 | sermons and guidance; |

| 10.0012.00 | a) visiting temples to pray; b) careful cleaning of alms, pots, and clothes; c) begging food and alms (Digambar); d) eating meals; |

| 12.0014.00 | services to seniors, self-study, meditation and rest; |

| 14.0017.00 | self-study, sermonizing, guidance, and receiving visitors; |

| 17.0018.00 | careful cleaning of belongings; |

| 18.0020.00 | evening penitential retreat, meditation and teaching the laity; |

| 20.0022.00 | religious discourses, reflection, and recitation; |

| 22.0004.00 | sleep |

Svetambar ascetics carefully clean their clothes and their wooden platters twice a day (pratilekhana or padilehan), and ensure that no harm is done to small beings when they use these possessions.

For every breach of the observances they confess to their senior, and seek atonement. Twice a year the ascetics remove their hair by plucking. They avoid intimacy with others and do not discuss worldly matters, except in the narration of stories, while teaching. They maintain minimal external contacts and concentrate on internal contemplation.

Jain nuns

Nuns (saadhvis) are an important part of the fourfold order of the Jain sangha. Since earliest times, the ratio of female ascetics to male ascetics, i.e. of nuns to monks has been in the region of 3 to 1. This situation continues to the present day, though in absolute terms the number of ascetics, male and female, is smaller than in the past; data from Jain texts suggests that in Mahavira's time approximately 10 percent of the Jain population were ascetics, of whom more than two-thirds were nuns.

Nuns observe the same rules as monks, including obedience to the senior nuns and gurus and to the (male) aacaaryas. Their daily routine virtually mirrors that of male ascetics, except for those areas of life unique to women. During a nun's menstrual period, she will not attend the temple, nor engage in study or teaching, and restricts her contacts with others; rituals, which would normally be undertaken in the company of other nuns, such as penitential retreat, are conducted alone and in silence. Jains believe that during this period, a nun (or woman) will not be able to 'communicate spiritual energy' due to the physical processes she is experiencing. Thus the recitation of mantras, to take one example, will be adversely affected by the biological state of the individual. This distorted consequence affects others, which is why nuns (and laywomen) temporarily withdraw from most activities and contacts during this short period and, for the duration of their menstruation, they occupy themselves in the silent repetition of prayers, mantras and in meditation. Often female ascetics will use this time to repair clothing and to spin wool, and also embroider the eight auspicious signs on woollen cloth for oghas, the soft 'brushes', which are the symbol of Svetambar ascetics, and which are used to clear the ground of small living beings.

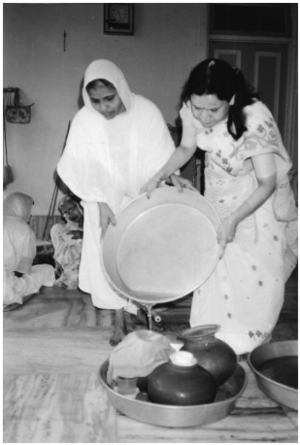

Plate 5.1-2 Svetambar 'nun' filtering drinking water and showing compassion to the living beings in the filtrate

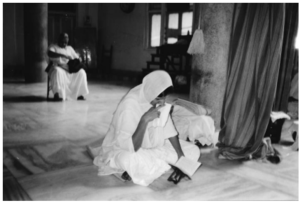

Plate 5.3-4 Svetambar 'nun' paying respects to the senior 'nun' and her self-study.

Some present day female ascetics have high academic qualifications and are proficient in scriptures, giving sermons and lectures, have an excellent rapport with laywomen and with children, and are especially noted for their renderings of popular devotional songs.

It must, however, be admitted that there is a disparity of status between monks and nuns among both Svetambars and Digambars. The Digambar nuns have a status equivalent to the eleventh stage of ethical progress (see chapter 4.10) and are, therefore, both technically and practically inferior to monks, but the Svetambars accord higher status to nuns and believe that women are capable of liberation. Candana, the head of the order of nuns in Mahavira's time, and Rajul, who was betrothed to the tirthankara Neminath, are among sixteen women included in the recitation for the morning penitential retreat on account of their exemplary spiritual qualities. Svetambars believe that the nineteenth tirthankara, Mallinath, was a woman in her last life before achieving liberation. The laity accord a similar respect to all ascetics, regardless of gender. However, in the hierarchy of ascetics, monks are accorded a higher status.

The laity and their duties

The Kalpa Sutra notes that the fourfold Jain community of Mahavira's time comprised of 14,000 monks, 36,000 nuns, 159,000 laymen and 318,000 laywomen. Monks and nuns rigorously followed Mahavira's teachings, while the laity followed within the confines of their everyday duties. While those born in a Jain community clearly have a better chance of learning the Jain path to spiritual progress, anyone who follows the teachings of Mahavira, consciously or otherwise, can be regarded as following the Jain path.

Jainism believes that all souls, with the exception of a very few 'undeserving' souls, can achieve salvation provided they follow the path of the Three Jewels, i.e. Right Faith, Right Knowledge and Right Conduct.

The ascetics refer to the laity as sraavaka and sraavikaa, words which, in Indian scripts, consist of three syllables representing the entire Jain philosophy, and its goal of liberation through the Three Jewels:

| sra | listening (hearing and accepting teachings, i.e. Right Faith) |

| va | knowledge (i.e. choosing Right Knowledge) |

| ka | action (i.e. performing Right Action) |

An older designation for a layperson was upaasaka, which means 'one who aspires to liberation'.

The Jain texts describe two types of layperson: the actual and the ideal. The actual followers of the faith ('householders') should endeavour to turn themselves into the ideal, by observing the vows prescribed for them. Householders who do not observe any vows, even if born into Jain families, are not designed as Jain laypersons. Thus, we could construct a sequence beginning with 'ordinary people' who do not follow the Jain path, then progressing to the actual lay followers (householders), and culminating with the ideal lay followers who observe their vows. Beyond this stage are the ascetics, the enlightened ones and, finally, the liberated ones.

The traditional Jain texts, being didactic in nature, normally describe only ideal laypersons, i.e. those who follow the appropriate vows. The only literary references to 'ordinary' people come from the narrative literature.

Jain scriptures also distinguish between the 'sraavaka by name' (dravya sraavaka) and the 'sraavaka by heart' (bhaava sraavaka). The former, although identified as Jain by birth, may not be living a Jain life. On the other hand, the latter has Right Faith and follows Mahavira's teachings. Both the actual and the ideal laypersons are considered bhaava sraavakas.

In chapter 4.10, we described a set of thirty-five rules of conduct and twelve vows for the householder. If a householder belonging to another faith follows these rules of conduct, he or she may be considered a Jain.

One who observes the twelve vows is considered to have reached the utmost limit of the practice for a non-ascetic; this level of observance is termed as partially restrained religion (desavirati dharma). Some people progress to an ascetic life and observe the totally restrained religion (sarvavirati dharma). Digambar texts describe eleven 'model stages' leading to being an 'ideal' layperson, equivalent to desavirati dharma.

Daily duties of Jain Laypersons

Jain texts such as the Dharma Sangraha, Sraddhaa Vidhi, Upadesa Prasaada, Sraavaka Prajnapti, Rantna Kaanda, Pujaa Pancaasaka, and Sraavakaacaara describe the daily duties of the laity, and their duties for holy days, the rainy season, duties of the year and through life. They give guidance on choosing a residence, a profession, marriage and family issues.

The layperson is expected to carry out certain religious obligations in a uniform round of daily duties. The daily duties may be modified, depending upon time and place, and available means of worship. Svetambar laypersons follow a daily routine of morning recitations upon awakening. These are three, six, nine or twelve silent recitations of the Namokara Mantra, holding both hands out together, palms upwards, forming thereby the shape of the abode of the liberated (siddha silaa).

Homage is paid to the liberated as examples of purification. Some may recall past pilgrimage to places such as Satrunjay, Sammeta Sikhara, Sankhesvara, Taranga, and Girnar as a form of meditation. At the same time laypersons decide upon any renunciations which might be undertaken that day. The householder, in India normally the women, sweep the floor to avoid harming any tiny creatures, filter the water and clean the utensils. Then after performing their daily ablutions, physical and psychical pujaa of the Jina image in the home shrine is undertaken, followed by the appropriate form of renunciation and atonement for the time of day. The householder, usually the woman of the house, also lights a lamp (of ghee) in front of the image.

The minimum renunciation undertaken by most laypersons is navakaarsi, the vow to avoid eating and drinking for forty-eight hours after sunrise. Some then go to the temple for worship and then seek their religious teachers, pay respects to them and listen to their sermons, perform various personal services for them, including the provision of medicines for the sick. Laypersons are expected to perform six essential duties (aavasyakas): 'equanimity' (saamayika); veneration of the twenty-four tirthankaras (caturvisanti stava); veneration of ascetics (vandanaka); penitential retreat (pratikramana); renunciation (pratyaakhyaana); meditation with bodily detachment (kaayotsarga). They would then normally proceed to their day's work.

At noon another pujaa is performed, then after providing food and other necessities for ascetics, householders take their midday meal. A reaffirmation of renunciation and a short meditation on the meaning of the scriptures may follow. Work then resumes until the evening meal, after which the family undertakes the evening pujaa, normally in the temple, which includes the lamp-waving ritual and evening penitential retreat. Some self-study follows and any necessary services for ascetics are carried out. Then the layperson will normally retire to sleep meditating on the Namokara Mantra. Jains do not normally eat after sunset, are lacto-vegetarians and avoid root vegetables.

With regard to the professions of laypersons, these must avoid violence as far as possible and be done honestly. Bhuvanbhanusuri (aacaarya of the late twentieth century) indicates to the laity that earnings should be utilised as: family maintenance and welfare, 50 percent; savings (e.g. for retirement or contingency), 25 percent; and religious (or philanthropic) activities, 25 percent, but very few practise this today.

Jain laypersons have daily duties, some for ordinary days, additional ones for regular holy days and special days. There are also annual and 'lifelong' obligations; these are described in chapter 5.2. Digambars have similar daily duties, with only minor variations. Sthanakvasis perform the above daily duties but do not attend temples for worship. However, in Leicester, owing to moves to greater unity among Jains, all sections of the community follow the same ritual pattern, and this tendency is seen in some other Jain centres in the West.

Lay Women: Laywomen have always been the largest constituent of the fourfold order, but the patriarchal mentality has led to the expression of negative and degrading remarks about women in some of the later texts. However, most Jain seers have stated that women possess the highest spiritual capacity and pronounced them the equal of men.

As mentioned earlier, Svetambar women can be initiated as nuns, but Digambar women can take vows to a degree short of the complete ascetic life. When they take the vow of celibacy and they are called brahmacaarini, and they become aaryikaa at the final stage of their spiritual progress.

Laypersons today: The conduct of the laity described above is an ideal, but it is generally difficult to maintain ideals. Since medieval times, a large number of changes have taken place in India; life has become more and more complex; and many laypersons cannot observe the ideal conduct even if they wanted to. The problem is even more acute for those Jains who have settled outside India; in an increasingly materialistic world, busy life styles and the lack of support from the ascetic orders have created a serious disadvantage to following the Jain path. However, most have remained vegetarians, have some sort of place of worship in the home and perform individual rituals.

Animals as Laity

Jainism believes in the concept of spiritual advancement for animals (Aupapaatika Sutra: 1992: 118) and indicates that instinctive animals possessing five-sense such as elephants, frogs, snakes and lions can behave spiritually as lay Jains, as they have:

- the instinct for the desirable and avoidance of the undesirable

- a discriminating capacity for good and evil

- a capacity to remember their past lives

- the capacity to fast, perform penance and the will for self-control

- the capacity to hear religious sermons and receive instructions

- the capacity to acquire sensory, scriptural and clairvoyant knowledge.

It is claimed that the holy assembly of Mahavira consisted of living beings of all forms, and his sermons were in a language, which miraculously could be understood by all. Tamed animals follow instructions; police forces use dogs extensively for a wide range of tasks; and animals are often more reliable friends than human beings. Many birds and animals do not eat at night; many are vegetarians and do not harm others; and they do not compete for the food. They live in communities; their activities are limited to the natural instincts for obtaining food, sex for reproduction, sleep, and reactions to fear. If we think about their behaviour, they live a life similar to that of the laity.

Jain scriptures contain stories of the elephant Meghaprabha, the cobra Candakaushika, a frog who worshipped, and a lion listening to the sermons in an earlier birth of Mahavira. Jains believe that animals can behave like the human laity, progress spiritually and improve their future rebirth, and the Jain scriptures claim that there are more animals, following the life of the Jain laity in the universe, than humans. Hence Jainism stresses the importance of animal welfare and shows compassion towards them; and one finds a respect for animals among practically all members of the Jain community.

Dr. Natubhai Shah

Dr. Natubhai Shah