Jainism has been a living faith in India for thousands of years, and it has contributed a long and significant heritage to Indian art and culture. Jains love both literature and art, and they believe them to be of a great aid in promoting the values of their faith. As a result of royal patronage and the patronage of wealthy Jains, in practically all parts of India, there are stone inscriptions; the remnants of stupas (sacred mounds), cave temples, freestanding temples and images. Jain sastra bhandaras (libraries) and temples have preserved the rich treasures of their art and culture. Some of these artefacts are very ancient: including, manuscripts on palm leaves and paper, covering a variety of subjects both unadorned and highly decorated with paintings; painted and embroidered wall hangings (patas) on cloth or paper, both for daily and tantric (using mystical formulas) worship. The artwork also includes diagrams and illustrations from Jain cosmology; scrolls with illustrations of artefacts, jyotisa (astrology, dreams and omens) and vijnapti patras (letters of invitation to ascetics) on painted or embroidered scrolls. Jains have also preserved fine pieces of artwork such as painted wooden boxes and book covers for manuscripts; the artwork of shrines; statues in stone, metal and semi-precious and precious stones; and sculptures and woodcarvings.

Jain art has been essentially religious and, it would appear, the Jains carried their spirit of acute enquiry and even asceticism into the sphere of art and architecture, so much so that in conventional Jain art, ethical subjects seem to predominate. There are minute details in texts, such as the Maanasaara (circa sixth-century CE), showing a conventional system of sculpture and architecture to which artisans were expected to conform without deviation (Ghosh A. 1974:1.37)

It should be noted that when we speak of 'Jain art' (or architecture) we mean art produced for Jains. Invariably, the artists themselves would not be Jains but specialists in the fields of painting, sculpture and so on, who could produce work conforming to the iconographic and other conventions demanded by the Jains commissioning their work.

The most distinctive contribution of Jainism to art is in the realm of iconography, as Jain teachings oblige the laity to contribute towards temples and icons, according to their means, at least once during a lifetime, as the merit earned by this helps the devotee to cross 'the ocean of worldly life'.

Jain images are serene and happy in expression and may be seated or standing in meditation. Some have their retinue (parikar) around them. Their gaze is focused on the tip of the nose and they wear a benign expression. The contribution of northern India to the development of Jain iconography is very significant. According to the Jain tradition, all twenty-four tirthankaras of the present era were born in this region, and it was in this region that most of the Jain deities first gained sculptural representation.

Iconography

The Jain 'virtuous meditation' (dharma dhyaana) describes the meditator, the objects of meditation, the technique of meditation and the result of meditation (liberation). Of these, the objects of meditation are of particular importance to Jain iconography. These are:

meditation on the nature of the living body (pindastha);

material representation of the jina (rupastha);

meditation on sacred mantras (padastha);

formless meditation on the soul or aatma (rupaatita).

The second form of meditation requires an image of the jina as its focus. Since the jina is attended by various classes of deities, Jain iconography has developed images of these celestial beings. The third type of meditation led to the development of sacred diagrams (yantras) and the printing of sacred formulas (mantras) (Jaini P. 1979: pp.254-256).

The Indus Valley civilisation (c.4,500-1,500 BCE) is the earliest civilisation of India. The figures on some of the seals from Mohenjodaro and a male torso from Harappa resemble Jina images on account of their nudity and posture. The earliest known jina image, preserved in the Patna Museum, comes from Lohanipur (Patna, Bihar) and is dated to about the third century BCE. It is thought that the main image of the Svetambar temple near Nalanda may also date from the third century BCE, and similar claims are made for the image in the temple at Valabhi (Gujarat) (personal communication 1992). Another jina image from Lohanipur is dated to the Sunga period (second century CE) or slightly later. Two bronze images of Parsvanatha, dating from the second to first century BCE, are in the Prince of Wales Museum, Bombay, and in the Patna Museum. One figure has a five-hooded snake canopy, the other a seven-hooded snake canopy; both are naked ('sky-clad'). They are in the standing meditation pose (kaayotsarga-mudraa). The cave inscriptions of Hathigumpha (Orissa), which are dated to c.125 BCE, make a specific reference to the 'Kalinga Jina' image, the removal of which by Nanda Raja almost led to war, and its restoration to its rightful place by Kharavela (Ghosh A. 1974: 1.74)

Mathura, in Northern India, was a stronghold of Jainism from c.100 BCE to 1177 CE. Early Jain sculptures from Mathura are of special iconographic significance, because they exhibit certain formative stages in the development of Jain iconography. The rendering of jinas in the seated cross-legged pose (dhyaana-mudraa), and the placing of a diamond-shaped emblem (srivatsa) in the centre of each jina's chest, appear for the first time in the Sunga Kusana (second to fourth century CE) sculptures of Mathura. The Gupta period (fourth to seventh century CE) saw significant developments in Jain iconography; some distinct iconographic features were introduced such as the distinguishing symbols (lanchana) which are engraved on the front of the base of jina images, as was the veneration of images of 'guardian deities' (yaksas and yaksis) (Tiwari M. 1983: p.3).

From the 9th century CE onwards, sculptural architecture made rapid strides under the Candella dynasty of Budelkhand, the Solankis in Gujarat, and the Pandyas, Gangas and Hosyalas in Karnataka. The finest examples of fine Candella art are still to be seen in three large and half a dozen smaller old temples at Khajuraho, which were built in the tenth to eleventh centuries CE. Of the three large temples, known as the Parsvanatha, the Ghantai and the Adinatha, the Parsvanatha is the best-preserved finest temple at Khajuraho built in tenth and eleventh century CE (Deva K 1975: p.257).

The Jain literature and art thrived between the tenth and fifteenth centuries CE, which also saw the building of Jain temples with exquisite sculptural carvings. Gujarat and Rajasthan became the strongholds of the Svetambar sect, while in other regions the Digambar and the Yapaniya sects flourished.

The tradition of carving twenty-four 'guardian attendants' (devakulikas) with the figures of the twenty-four jinas became popular at Svetambar sites. Digambar jina images of this period show, in the retinue of the jinas, the figure of Neminath, accompanied by a pair of guardian deities; the figures of goddesses, such as Laksmi and Sarasvati; Bahubali, Balarama and Krishna; and representations of the nine planets (nava grahas). At Svetambar sites, the inscription of the names of the jinas on their pedestals was preferred to the use of distinguishing symbols, but later practice reverted to the use of symbols. From the eleventh century onwards, Svetambar temples in western India accorded the sixteen goddesses of learning (vidyadevis) a position second only to the jinas; an early example can be seen in the ceiling carvings of the temple at Kumbharia (Gujarat).

The number of figures of male deities in non-jina sculptures is small when compared with representations of female deities, probably owing to the influence of Hindu worship of Sakti. The facade of the Parsvanatha Jain temple at Khajuraho (950-70 CE) shows divine figures embracing Sakti; these include the Hindu divinities Siva, Visnu, Brahma, Rama, Balarama, Agni and Kubera. It includes secular sculptures on domestic scenes, teacher and disciples, dancers and musicians, and erotic couples or groups. Such erotic figures are antithetical to the accepted norms of Jain tradition and show the influence of the brahminical temples nearby (Deva K. 1975: pp.266-267).

Jain Divinities: The Jain pantheon had evolved by the end of the fifth century CE, largely consisting of the twenty-four jinas, and the figures referred to above. The lives of the sixty-three 'torch bearers' (salaakaa purusas) became favourite themes in Jain biographical literature. These included 24 jinas; 12 'universal emperors' (cakravartis), such as Bharata and Sagara; nine baladevas, such as Rama and Balarama; nine vasudevas, such as Laksmana and Krisna; and nine prati-vasudevas, such as Bali, Ravana and Jarasangha. Detailed iconographic features of these deities developed between the eighth and thirteenth centuries CE (Tiwari M. 1989: p.6).

Jinas: The jinas occupy the most exalted position in Jain worship. As a consequence, the jina images outnumber the images of all the Jain deities. The jina images denote psychic worship and not physical or image worship. It is regarded as worship, not of a deity, but of a human being who has attained perfection and freedom from bondage, as exemplary. The detached jinas neither favour nor disfavour anyone. Because of this, jinas were always represented only in the seated or standing attitude of meditation, while the Buddha, in the course of time, came to be represented in a range of different poses, such as offering his blessings. Unlike the Buddha, none of the jinas was ever credited with the performance of miracles.

Lists of the twenty-four jinas were in existence some time before the beginning of the Christian era. The earliest list occurs in the Samavaayanga Sutra, Bhagavati Sutra, and Kalpa Sutra (third century BCE), and we know that concrete representations of the jinas began to appear in about the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE. The Kalpa Sutra describes at length the lives of jinas Risabhdeva, Shantinatha, Neminatha, Parsvanatha and Mahavira. Of the other jinas, Ajitanatha, Sambhavanatha, Suparsvanatha, Candraprabha, and Munisuvrataswami were the most favoured. Figures of these remaining jinas are few in numbers.

Of the jinas, the iconographic features of Parsvanatha were the earliest to be finalised. The seven-hooded cobra canopy was associated with him found about the firstcentury BCE. Around two centuries later, Risabhdeva was represented with long flowing hair, as is evident from sculptures at Mathura and Chausa.

Balarama and Krishna became members of Neminatha's retinue, as can be seen in sculptures from Kankali Tila, Mathura. During the Kusana period (1st century CE) images of Sambhavanatha, Munisuvrata, Neminatha and Mahavira were carved; identification rested solely on the basis of pedestal inscriptions of names, no other iconographic devices were employed. By the end of the Kusana period, the following seven of the eight 'divine distinctions' (pratihaaryas) were found at Mathura:

| the chaitya tree | the shower of flowers |

| attendants with sacred fans | the divine throne |

| the divine parasol | the halo |

divine sound (represented by drums and singers).

The rendering of the distinguishing emblems of the pairs of guardian deities and all the eight divine distinctions of the jinas which marks a significant development in jina iconography, started as early as the Gupta period. The Neminatha image from the Vaibhara hills (Rajgir, Bihar) and the Mahavira image from Varanasi (now in the Bharat Kala Bhavan, Varanasi) are the earliest instances of images showing the eight divine distinctions. The Risabhdeva images from Akota, and the Mahavira images from Jain caves at Badami and Aihole (Bijapur, Karnataka) are the earliest jina images with figures of guardian deities in the retinue. The representation of tiny jina figures carved on images of divine thrones and in jina retinues is first appeared in the Gupta period.

The list of the distinguishing emblems of the twenty-four jinas was finalised around the 8th or 9th centuries CE. The earliest literary references to them are found in the Tiloyapannatti, the Kahaavali and the Pravacanasaaroddhara. The fully developed jina images invariably contain distinguishing emblems, pairs of guardian deities, eight divine distinctions, the wheel of law with worshippers, diminutive jina figures and, at times, nine planets, the goddesses of learning and elephants washing the jinas. The carvings of narrative scenes from the lives of the jinas occur mainly at Jain sites in western India. Examples from the 11th to 13th centuries deal chiefly with the five 'auspicious events' (panca-kalyanakas), conception, birth, renunciation, omniscience and liberation of the jina. But they also deal with other important events in the lives of Risabhdeva, Shantinatha, Munisuvrata, Neminatha, Parsvanatha and Mahavira. Of these, the representation of the fight between Bharat and Bahubali; the story of the previous life of Shantinatha, in which he generously offered the flesh of his entire body to save the life of a pigeon; the trial of strength between Krishna and Neminatha; the marriage procession of Neminatha and his consequent renunciation; the story of Asvabodha and Sakunika-vihaara in the life of Munisuvrata; and the previous births of Parsvanatha and Mahavira along with their austerities and meditations, are of particular iconography interest. (Tiwari M. 1983: pp.5-7).

Objects of worship

Images: The material form of jina images is one of the most important objects of meditation and worship. Scriptures and texts relating to consecration contain numerous formulae regarding jina images-postures (seated or standing); measurements of the relative proportions of the limbs, head and fingers; the 'auspicious marks', e.g. the lotus shaped chest mark (srivatsa), the head protuberance (urnisa), the guardian deities and divine musicians.

Jina images have varied forms: the single image, the double, triple, quadruple or quintuple images, and in some instances images of all twenty-four jinas on a single slab or within one frame. The quadruple image may be of the same jina or of different jinas on each of the four sides. The double, triple or quintuple are conventionally of different jinas. Iconography developed independently in three geographical areas: Gandhara in the northwest (now Pakistan), Mathura in northern India and Amaravati in southern India.

The statue of Gommateswara Bahubali at Sravanbelgola (981 CE) is nineteen metres high and sculpted from a single rock and is the largest freestanding monolithic image in the world. It symbolises complete detachment from the world, an aspiration for all Jains (Doshi 1981: p.10) Among Jain sculptures, the jina images provide the artist with little scope for the display of individual talent, due to the prescribed conventions. But, in the representation of guardian deities, Sarasvati, the goddess of learning, the nine planets, the spatial deities (ksetrapalas), the worshippers, and in decorative motifs, the artist was not constrained by prescribed formulae and exercised greater freedom. Artistic genius produced art and sculpture of immense aesthetic beauty. Jain art has produced intricately decorated scriptures, votive tablets, stone balustrades, pillars, architraves, walls, balconies, ceilings and domes seen in the earlier cave temples, such as Ellora, through to the medieval temples, such as those at Khajuraho, Delwara and Ranakapura, and to the recently consecrated temple at Leicester in England.

Yantras: The siddhacakra, the wheel of salvation, is one of the most popular mystical diagrams (yantras) of the Jains. Digambars often personify it as the 'nine adorable ones'. It depicts an enlightened one, a liberated one, an aacaarya, an upaadhyaya, an ascetic, Right Faith, Right Knowledge, Right Conduct and austerity. Some devotees use it for daily worship, while others use it for the elaborate ceremony of siddhacakra mahaapujana. In this elaborate ceremony, the siddhacakra is made from coloured rice grains and includes in its representations the sixteen goddesses of learning, guardian deities, the nine planets, Brahma, Indra, the Moon, and the four spatial deities.

Plate 6.1 Brass Jina Statues with the Siddhachakra Yantra at Jain Centre, Leicester

Other yantras: Stotras are prayers describing and praising, in an ornate and metaphorical manner, the qualities of the jina. In the course of time, mystical diagrams of these stanzas or the sounds om and om arham or om hrim, representing the five supreme beings, became the key syllables for the preparation of mystical formulae and yantras. Jain literature lists numerous mantras, their meditation and their spiritual benefits. Some yantras have been developed on specific mantras.

Most yantras are either circular or square with mystical formulae often inscribed in concentric circles. Sometimes, in the middle of the circle there is a lotus or a square made up of several segments in which the syllables are written. Some yantras are in the form of a swastika (a symbol of the four destinies) or of a crescent moon, a tree, a boat, a lotus or an open palm. These yantras are painted on paper, cloth, a wooden 'table', or are embossed on metal plaques. Jain yatis and bhattarakas have developed yantras for specific devotional purposes, for example, the shantikarana yantra has been created as an object for meditation for those devotees who are seeking peace. These yantras are worshipped at home through prescribed repetitive incantations, and are believed to be of benefit for both physical and psychic wellbeing and prosperity.

The dharmacakra (wheel of holy law) was once an important object of worship, but today there is no ritual connected with it. It appears in the form of a bronze or carved object at the top of a pillar, on a stand, or on a lintel and is held in position by two creatures such as deer. The wheel itself, in a decorative frame has sixteen spokes. On the pedestals of some early Jain images, a sixteen-spoked wheel is pictured surrounded by devotees. Later, the dharmacakra is depicted in profile, flanked by lions or deer. Emerging from the wheel is the noble representation of a human figure, a personification of the dharmacakra. Nowadays, the frieze also represents the fourfold order of the sangha, in the form of two groups of four standing male and female figures. It signifies peace, harmony, forgiveness, the interdependence of living beings and reverence for life.

Figure 6.5 The dharmacakra, 'wheel of religion'

The caitya and kalpa trees: The environmental concerns of Jains can be seen in the special importance given to trees as sacred objects of worship. Tree worship has been an important element in popular beliefs and practices since earliest times. Numerous stone images of the Jinas show them seated beneath trees; there are bronze images of Jinas in a meditating posture beneath trees, and there are images of the renunciation of Mahavira beneath an asoka tree and his enlightenment beneath a sala tree, and branches of an asoka tree are used in the pratistha, the consecration or installation ceremony (Ghosh A. 1975: 3.486-487).

The mound (stupa) and the votive column: Jain literature refers to the building and worship of mounds. Such mounds and commemorative columns were mainly funerary monuments. The later traditions of installing 'vanity-subduing pillars' (maana stambha) or 'pillars of glory' (kirti stambha) may have developed from the commemorative column. o intact structure of any ancient Jain mound has survived, although the remnants of the mound built at the site of liberation of Mahavira still exist (at Pavapuri). Its circumference proves that it must once have been an immense structure (1992; personal observation).

Plate 6.2 Kirti Stambha, Ahmedabad.; erected for the 2,500th nirvana anniversary of Mahavira. (Photo courtesy of Dr W. Johnson)

Remains at Kanakali-tila in Mathura region show a ground plan in the shape of an eightspoked wheel over which a structure was built of brick. Somadeva (tenth century CE) refers to a 'mound created by heavenly beings' which existed in his day in Mathura (Ghosh A. 1975: p.53). In the Jambucarita, Rajanabha refers to more than 500 mounds in Mathura, during the time of Akbar. According to Jain mythology, mounds with jina images over them were constructed around the jina shrine. We find at many (Digambar) sites free standing pillars in front of Jain temples in southern India (where the temple complex is called a basadi), and some in northern India. The Mathura Jain pillar (c. 116 CE), the Kahau(m/n) Jain pillar with the images of five jinas carved on it (160 CE), the Deogarh pillar (862 CE), and the pillar of glory at Chittor (circa. thirteenth to fourteenth century CE), are the most important north Indian examples from ancient and medieval times. During the past century numerous such pillars have been constructed in different parts of India. The Jains generally refer to these pillars as 'vanity-subduing pillars', the prototypes of which they believe, in Mahavira's time, stood just within the main entrance to the holy assembly hall (samavasarana) of the jina, the temple itself representing the holy assembly. They are tall elegant structures, well-proportioned and decorated with a small pavillion on the capitol, surmounted by a pinnacled dome (sikhara), and images (usually four) of the jina installed in the pavilion. They are quite different from the 'lamp pillars' (dipa stambhas) of Hindu temples, or the 'pillars of glory' (kirti stambhas) of the conquerors.

The Aayaagapata: Jain literature refers to stone slabs (silaapata), slabs of earth and stone (prithvi silaapata) and votive slabs, i.e. slabs for offerings (balipata). These slabs themselves have come to be regarded as sacred objects and are usually square or oblong, about 60 to 90cm in length, show symbols of the Jina or the human form of Jina, and sometimes inscriptions naming a donor. Votive slabs are found only in the Mathura region. The practice of installing and worshipping votive slabs seems to have been discontinued since the end of the Kushana period (Ghosh A. 1975: 64).

In many modern temples slabs for offerings, carved on the upper surface with eight auspicious symbols, are placed so that worshippers can make replicas of auspicious symbols with rice-grains. However, in every temple a simple offering table is placed in front of a shrine. On this, devotees arrange:

- rice grains in the shape of the swastika to symbolise the cycle of transmigration through four destinies, and nandhyavarta (a complex and elaborate swastika, an auspicious symbol of ninefold prosperity)

- a piece of sweet material to symbolise the attainment of a state in which food is not needed

- a piece of fruit symbolising the attainment of siddha-hood.

The sthaapanaa, also known as the thavani or sthaapanaacaarya, is a crossed book rest or stand made of two flat pieces of wood or four ornate small sticks of wood tied together with thread in the middle and splayed out above and below so as to look like an hour glass, on which any object of worship (usually a scripture) is placed by an ascetic. While preaching a sermon the ascetic keeps the sthaapanaa in front of him or her. In daily rituals such as penitential retreat, the ritual of equanimity or a sermon, laypersons also keep the sthaapanaacaarya in front of them. It is seen as a representation of the guru.

The astamangala: Svetambars believe in eight auspicious symbols:

- the auspicious symbol of the four destinies (swastika);

- the lotus shaped mark on the chest of the Jina image (srivatsa);

- the elaborate symbol of nine fold prosperity (nandhyavarta);

- the 'prosperity pot' (vardhamanaka);

- the throne (bhadraasana);

- the holy jug (kalasa);

- the pair of fish (minayugala);

- the mirror (darpana).

The Acaara-Dinkara Grantha (1411: pp.197-198) explains the conception behind each of these symbols: swastika for the peace, srivatsa for highest knowledge from the heart of Jina, nandhyavarta for nine forms of treasures, vardhamanaka for the increase in fame, prosperity and merit, bhadrasana as an auspicious seat sanctified by the feet of Jina, kalasa is symbolic representation of Jina's attributes to be distributed in the family, minayugala as the symbol of Cupid's banner suggesting that the devotee has conquered the deity of love, and darpana for seeing one's true self. The Digambars recognise eight auspicious symbols: a type of vessel (bhringaara), the holy jug (kalasa), the mirror (darpana), the flywhisk (caamara), the flag (dhvaja), the fan (vyajana) the parasol (chatra) and the auspicious seats (supratistha) (Ghosh A.1975: P.3.489, 492)

From canonical texts onwards there are innumerable references to these eight auspicious items, which are held in great reverence by the Jains. Often, in modern temples, generous patrons donate images or plaques of places of pilgrimage or incidents in the life of a Jina, in stone, metal, mirror and painted cloth. These auspicious things, along with the fourteen auspicious dreams appear on the door lintel or window frame of domestic shrines or temples; especially those made of wood. The metal plaques depicting these auspicious symbols are found in front of the main image in many temples. These symbols are found on book covers, in miniature paintings, on invitation scrolls to ascetics, invitations for consecration or installation ceremonies, special rituals and other similar religious events. Svetambar ascetics wrap the handle of their soft woollen brush (caravalaa) in three different cloths; one of these wrappers is of wool, on which the eight auspicious symbols are embroidered.

Guardian deities: The demi-gods and celestial beings of the Jains are known as the guardian deities of the sangha (saasanadevas), although they are secondary deities, they are accorded the second most venerated position after the Jinas. The Jain scriptures describe them as capable of pacifying the malevolent powers of the planets and peripatetic celestials such as ghosts, fiends and demons. According to Jain belief, the celestial King Indra, appoints demi-gods, usually in couples, to serve as attendants upon every Jina. In Jain representations they possess divine attributes and symbolic meanings. Over time, devotees elevated their position until some of them became worshipped as independent deities. The Jain texts from the sixth to ninth century CE note a few of the iconographic features of the demi-gods Sarvanubhuti and Dharanendra, and the demigoddesses Cakresvari, Ambika and Padmavati. The literary as well as archaeological evidence suggest that from between the tenth and thirteenth centuries CE the demi-god Sarvanubhuti, and demi-goddesses Cakresvari, Ambika, Padmavati and Jvalamalini, attained such a position that independent cults developed around them. The demi-gods have both benign and malign aspects: as benign celestials they bestow happiness upon devotees and fulfil their wishes, as malign they can create disaster. Currently, the popular demi-gods and goddesses are Manibhadra, Gantakarna Mahavira, Nakoda Parsvanatha, Padmavati, Cakresvari, Ambika and Bhomiyaji, but this varies from temple to temple.

The list of the twenty-four pairs of guardian deities, attendant on each jina, was finalised in about the eighth or ninth centuries CE. By contrast, their independent iconographic forms were standardised only in the eleventh or twelfth centuries. Vidyadevis: After the jinas and their guardian deities, goddesses of learning (vidyadevis) enjoy the highest veneration among both major sects. These goddesses form a group of tantric deities. Mantras and exercising their power have been assimilated into Jainism for securing peace and tranquillity of body, mind and soul. The Jains apparently became conscious of the goddesses of learning from at least the fifth century CE, although there are some stray references to them even in earlier canonical works.

The Jain tradition speaks of as many as 48,000 goddesses of learning, of which only sixteen are considered to be supreme; their earliest lists date from the ninth or tenth centuries CE. They are enumerated in various Jain texts such as the Stuti-Caturvinsatika and are: Rohini, Prajnaapti, Vajrasrunkhala, Vajrankusa, Apraticakra or Cakresvari (Svetambar), Jambunada (Digambar), Naradatta or Purusadatta, Kaali or Kaalika, Mahaakaali, Gauri, Gaandhaari, Sarvastra-mahaajvala (Svetambar), Jvalamaalini (Digambar), Manavi, Vairotya (Svetambar), Vairoti (Digambar), Acchupta (Svetambar), Acyuta (Digambar), Maanasi and Mahaamaanasi. Sculptures of these goddesses, crowned by tiny jina figures and having between four and eight arms, in a seated posture or standing, bear various attributes with their respective vehicles. Jains worship Sarasvati as 'goddess of scriptures' (srutadevi), her image being found in many temples (Tiwari M 1989: pp.11-14).

Cave temples

Caves are conducive to meditation. Hence, from early times, Jains built temples either in natural caves or by digging into rock and decorating it with pillars, doors and carvings, or decorating the inside of the cave walls. The most famous of them are in the hills of Girnar, Nagarjuna, Jogimira, Khandagiri, Tankagiri, the Sona cave near Vibharagiri, Badami, Madurai and, at Ellora, the smaller Kailasa, Indra Sabha and Jagannath Sabha. Jain cave temples continued to be built until the tenth century CE Jain cave temples progressed from a simple plan within a small space, with a rectangular pillared verandah and a square pillared hall, to the magnificent temple at Ellora. At Ellora, a two-storied monolithic temple is cut out of a mountain slope, with a large pinnacle, a courtyard flanked by a two-pillared pavilion or porch, and an upper story with a central pinnacle connected to two smaller shrines. Some temples contain highly sophisticated carvings, paintings, mirror work and other works of art depicting the five auspicious events in the life of the Jina, or other religious themes.

Usually, Jains showed great taste in selecting the best sites for their temples and caves. At Ellora, they arrived when the Buddhists and the Saivas had already appropriated the best sites, but elsewhere, as Longhurst notes, 'unlike the Hindus, the Jains almost invariably selected picturesque sites for temples, valuing rightly the effect of the environment on architecture' (quoted in Ghosh 1974: p.39). Good examples are at Sravanbelgola, Mudabidre, Sammeta Sikhara, Rajgir, Pavapuri, Mandargiri, Khandagiri, Udayagiri, Sonagiri, Deogarh, Abu, Girnar and Satrunjaya. The Jains also published works such as a 'Treatise on civil engineering' (Vastusastra), a 'Text on the construction of buildings' (Prasada-mandana) and a 'Handbook of houses, temples and iconographic architecture' (Vatthu-saara-payarana) by Thakkar Pheru, a fourteenth century Jain engineer from Delhi. This work enumerates twenty-five different kinds of temple buildings, and served as a practical handbook for architects of Jain temples throughout the medieval period. Recently, much temple building work has been done by the Sompuras, the architects (silpis), who have published two books on the subject.

Paintings

Jains have a long tradition of carved or painted temple walls, ceilings, pillars, doors and the interiors of shrines, but nothing has survived to illustrate the earliest periods. The Pallava King, Mahendravarman I, is believed to have been responsible for the murals at Sittannavasal, near Tiruchchirapalli in Southern India in the seventh century, and the Pandya kings are believed to have continued the tradition of Jain paintings (Ghosh A. 1975: 2.381). Surviving early mural paintings depict the auspicious events of a jina's life, guardian deities, ascetics, royal couples, temple dancers or natural landscapes. In the Indra-Sabha cave temple at Ellora, the entire surface of the ceiling and walls is covered with a wealth of detail.

Ninth century Jain manuscripts are illustrated with topographical scenes and patterns of floral, animal and bird designs. The story of Bahubali, the spatial celestials, flying demi-gods (vidyaadharas), celestial musicians, episodes from the life of Risabhdeva, Neminatha and the story of Krishna, were popular themes of paintings. Painted scenes also became fashionable in Jain manuscripts, and fortunately some of them are preserved in the ancient library at Mudabidre, in southern India (Ghosh A. 1975: 2.386). The paintings, usually on large palm-leaves, are important both for the beauty of the script composing the text and the illustrations that accompany it. Inspired by Jain ascetics in northern India, wealthy Jains commissioned paintings, which are referred to in the Kuvalayamaala-Kaha, a Prakrit work composed by the Jain ascetic scholar Udyotana Suri (eighth century CE) at Jalor in Rajasthan. It notes a samsaara-cakrapata, evidently a painting on prepared cloth depicting the futilities and miseries of human life, as opposed to the joys of heaven. In the Aadipurana, Jinasena I (c.830 CE) mentions a 'school of painting' (patta-sala) in a Jain shrine. In the Vaaraanga-carita, Jataasimhanandi (c. 7th century) refers to a Jain temple and its 'small paintings' (pattakas), depicting the lives of the Jinas, famous Jain ascetics and the 'universal emperors' (cakravartis) (Ghosh A. 1975: 3.394-395).

Pattakas are early precursors of the numerous Jain cloth patas, paintings on cloth, metal, mirror, marble or stone which are found in most temples and are still produced to day. They depict the five auspicious events in the life of a jina; incidents from their lives and the lives of famous ascetics, laity and kings, places of pilgrimage; and Jain mantras, stotras and teachings. The most popular pata in the Svetambar tradition is that of the temples on the Satrunjay hills, which is placed on display twice a year for devotees who cannot undertake the pilgrimage at the traditionally expected time. In 1985, the Jain Centre in Leicester had commissioned a large painting on cloth, measuring 7 X 3 metres, depicting Satrunjay. The Leicester Jain Centre also has series of ten stained glass windows (probably a unique artefact in the Jain world), depicting the main events of Mahavira's life, and mirrored ceilings and walls, the colours, design and pattern of, which are considered a fine work of art. Such mosaic mirror work is found in some temples in India, the most famous of them being the temples at Calcutta, Indore and Kanpur.

Ascetics encourage devoted Jains to make an embroidered velvet cloth (choda) at the conclusion of the ritual of fasting, meditation and devotion (upadhaan). These are often fine works of art in themselves and are hung behind the preaching ascetic or the image of the jina in small temples.

Wooden carvings

Some of the most intricate and marvellous woodcarvings, which have survived the ravages of time, are found in Gujarat and Rajasthan, and most belong to a period ranging from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. The best examples of these are found in Jain homes, domestic shrines (ghara derasars) and wooden temples, and they contain superb artwork with figures, lattices and perforations.

Domestic Carvings: A Jain house usually has either a jina image or auspicious symbols (for e.g. the fourteen dreams) carved on its door lintel or window frame as an auspicious feature. Other decorations on frames include the depiction of the eight auspicious symbols, vina and floral patterns, and 'door keepers' (dvara paalas). One also finds features of the home, pillars, window and doorframes, door lintels, brackets, arches, ceilings, wall panels, and screens (jaalis) on the windows and balconies (jharokhaas) which are beautifully carved.

Pieces of furniture such as wooden seats (paats, bajoths), beds (divans), and cradles (jhulaas), are tastefully decorated. Other wooden articles such as the three or nine-cornered built-in cupboards, and the platform for standing water jars, and chests (pataaraas) are exquisitely carved.

Temple Carvings: Jain temples can be either domestic shrines or stone (or wooden) public temples. The former is a special feature of the Gujarati Jains and almost every (haveli) house of any means has its own shrine. One of the earliest dated home shrines is of Shantinatha, in the street known as 'Haja Patel's pola', in Ahmedabad (1390 CE), commissioned by Sheth Somji. It is a wooden miniature replica of a temple, with a pavilion 3.35 metres square, which has 17 concentric layers of carvings, made up of 250 individual pieces. It contains pillars, brackets and architraves, which are richly carved with animals, chariots, deities, celestial musicians and dancers in classical poses. Many other such domestic shrines are found in Gujarat. The National Museum, New Delhi, has an intricately carved pavilion of a domestic shrine, which was made, in the Baroda region. The Metropolitan Museum, New York, acquired one of the most exquisite examples of a Jain wooden temple, the Wadi Parsvanatha temple, built in 1594 in Patan. It has a dome, which is more than three metres wide, carved with concentric circles of figures of deities with ornamental borders. From the highest point hangs a pendant in the form of a lotus. Equally spaced around the interior are eight more figures, which represent female musicians and dancers, and between each pair sit three others, one male figure and two who appear to be attendants. The dome is supported on pillars and arches and there are intricately carved balconies and windows. Beneath the canopy of the dome there are figures of eight deities. Beneath this intricate upper part of the temple, one finds a dado running round the entire length of the walls. It has niches in which there are, inter alia, carvings of musicians, dancers and rows of geese. Beneath the windowsills are carved rosettes that produce a pleasing aesthetic effect. Such small wooden carved temples and similar pieces of intricate figure carving are still made by skilled artisans in Gujarat and other parts of India.

Sculptures

Jains believe that a sandalwood sculpture, Jivantsvami image, of Vardhamana Mahavira was carved in his lifetime while he was meditating about a year prior to his renunciation in the 6th century BCE (Tiwari M. 1983: p.2). Later, the tradition of woodcarving in the round depicting jinas was abandoned, because of difficulty in the daily worship of such images, and was replaced by marble, stone or bronze images. However, subsidiary and allied carvings have continued, and some of these can be seen in museums. Such sculptures include musicians, dancers, heavenly deities and animals. All these carvings, though small in size, reflect the tastes of Jains, their support for art works and the skilful artisans. Though mostly religious, these carvings provide us with a glimpse of the interesting social history of the period. In woodcarvings Jains preceded their Hindu or Buddhist counterparts (Ghosh A. 1975: 3.436-38).

Manuscripts

(Svetambar) Palm-leaf period: The earliest illustrated Jain manuscript is on palm-leaf and contains two texts, the Ogha-niryukti and Dasavaikalika-tika, dated to 1060 CE (Shah U. 1978: p.7) The superior quality of the drawing in these manuscripts need not surprise us once we appreciate the fact that painting on cloth by skilful artists was practised long before the eleventh century. Illustrations on palm-leaf manuscripts became more commonplace over the centuries and it seems that their production was extensive in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

Wooden manuscript covers: In the manuscript libraries (sastra bhandaras) at Jesalmir are several painted wooden manuscript covers portraying beautiful paintings of Jain deities; others are also found in the sastra bhandara at Patan and in the L.D.Institute of Indology Museum, Ahmedabad. These painted covers of books on religious topics were commissioned in commemoration of an ascetic, for the presentation of a manuscript, to mark the occasion, such as the completion of the writing of the manuscript, or a consecration ceremony.

Paper Period: Though the use of paper for Jain manuscripts in Gujarat is attested to as early as the twelfth century, its use for illustrated manuscripts, on the available evidence, does not pre-date the fourteenth century (Ghosh A. 1975: 3.405). The production of manuscripts on palm-leaves continued up to the mid-fourteenth century. The Calukya rulers of Gujarat, Siddharaja Jayasimha (1094-1142CE), and Kumarapala (1142-1172CE), the famous banker-ministers Vastupala and Tejapala of the Vaghela kings, and Pethad Shah, minister of Mandal, were responsible for a number of manuscripts. U.P. Shah maintains that the earliest illustrated Jain manuscripts on paper are the Kalpa Sutra and the Kaalakaacarya-kathaa (1346 CE). The format is narrow, only 28 X 8.5cm, and the text only six lines of text on each leaf (Ghosh A. 1975: 3.406). The narrow oblong shape of paper manuscripts continues, of course, the form of older manuscripts written on palm-leaves.

Among other old illustrated manuscripts are the Kaalakaacarya-kathaa (1366 CE) in the Prince of Wales Museum, Bombay, the Santinatha-carita (1396 CE) in L.D.Institute of Indology Museum at Ahmedabad. The National Museum, Delhi has a Kalpa Sutra dated 1417 CE. The India Office Library, London has a Kalpa Sutra dated 1427 CE, which is elaborately decorated with the text in silver and gold ink. Over the centuries, as the availability of good quality paper and coloured ink improved, many beautifully decorated texts in gold, silver, red and other colours were hand written or printed. Recently Aacaarya Yashovijayji in Palitana has produced some of the most beautiful illustrated works, on the life of Mahavira, the daily life of ascetics and on some yaksis.

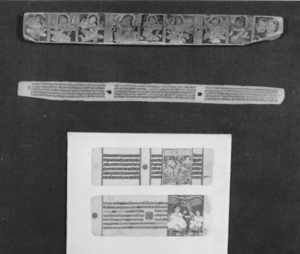

Plate 6.3 A wooden book cover and two pages of Jain scriptures. (Photo courtesy of L.D. Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad)

Plate 6 4 Dr L.M. Singhvi, High Commissioner of India in the U.K and the author, pay their respects to Aacaarya Yashovijay at Bombay, December 1995.

(Digambar) Manuscripts: Three palm-leaf manuscripts, the Satkhandaagama, the Mahaa-bandha and the Kasaayapahuda, all dating from about 1112-1120 CE, in the collection at Mudabidre, appear to be the oldest illustrated texts of the Digambars (Ghosh A. 1974: 3.411). The paintings consist of decorative medallions with a geometrical or floral pattern and portraits of divinities, ascetics, donors and devotees. The colours used are white, yellow, blue, red and black. The Khajuraho Jain manuscript library contains two manuscripts of 1107 CE.

Of the paper manuscripts in western India, no manuscripts prior to 1450 CE seem to have survived. The Tattvartha Sutra, the Yasodhara-carita, the Jasahara-cariu and other texts have been made by Bhattarakas from the 15th century onwards (Ghosh A. 1975: 3.412-13).

In northern India, the oldest illustrated manuscripts found, are the Aadipurana in Yoginipura (1404 CE), the Maha-purana in the Naya Mandir, Delhi (c.1420 CE) the Jasahara-carita (c.1434 CE) the Sangrahani Sutra (1583 CE), and the Yasodhara-carita (1589 CE). Illustrated Digambar manuscripts are few in number compared to Svetambar manuscripts. Both sects used the styles of manuscript illustration that existed in the region and executed many manuscripts during Moghul period. Jain manuscripts provide valuable clues to understanding life in the pre-Moghul period and also help to project the developments and ramification thereafter, thus contributing significantly to the history of Indian painting (Ghosh A. 1975: 3.426-27).

A serious and systematic assessment of evidence furnished by Jain temple, upashrayas and household libraries show that the objectives that guided Jain painting did not stem from aesthetic considerations, but from a desire to illustrate a religious theme. Miniature paintings are still included in modern publications on religious themes. Many libraries and museums contain Jain miniature paintings illustrating the Jain contribution to the heritage of India.

Calligraphy and Inscriptions

The art of the calligraphy and the decorating of palm-leaf, paper manuscripts and their covers were highly developed in medieval times. So was the art of inscribing on rock and on copper plates. The art of inscription has continued to the present day. Recent major works of inscription can be seen at Aagam Mandir, Palitana and also at Surat, where all the forty-five aagamas are inscribed on the inside temple walls in the most beautiful way. The royal banners of Jain kings contained emblems and symbols of Jainism. The earliest epigraphic record in the history of Jainism in eastern India is from the cave at Hathi-Gumpha in the Udaygiri hills near Bhuvanesvara, Orissa, dated first century BCE (Ghosh A. 1975: 1.74). Inscription records found in cave temples, temples, pillars, and on other architectural monuments, in practically all the languages of India, provide us with evidence on social conditions prevailing at the times they were made. This tradition of inscriptions has continued until modern times in most of the temples, upashrayas, educational and welfare institutions, which record the names of donors and philanthropists.

Other Works of Art

Jain Coins: Evidence of Jain influence on south Indian coins comes from a coinage attributed to the early Pandya dynasty between third and fourth centuries CE. Jain influence can be traced on some rectangular copper coins, which depict on their obverse certain symbols, usually, seven or eight in number, including an elephant. The 'goldenage' of Jainism in Karnataka was under the Gangas, who made Jainism their state religion (6th to 11th centuries CE). The famous Bahubali colossus at Sravanbelgola was created by Camundaraya, the famous Ganga General of the Hoysalas, whose kingdom was staunchly Jain. Hoysala kings also issued coins of gold and other metals inscribed with Jain symbols, and which are now considered works of art (Ghosh A. 1975: 3.456- 62).

Gold, Silver and Metal Work: On special occasions which attract many devotees, Jains, especially Svetambars, adorn images of a jina with a gold or silver crown, and body decoration (aangi) of intricate beauty, depicting the jina as an emperor or prince, as he was before renunciation.

In most temples one finds three vertically stacked wooden tables, and on the topmost is a throne for the image of a jina (tigadu). These tables with their fine artwork are made of wood, clad with silver or 'german silver' (a silver-like alloy) and are used as a replica of Mount Meru for ritual worship and pujaas.

Art objects in museums

In addition to the temples, upashrayas and sastra bhandaras, Jain artwork is found in museums in India as well as abroad.

Museums in India: The National Museum, New Delhi, has a rich collection of Jain sculptures and art from almost all regions of India. Sculptures and jina images, retinues, bronzes, paintings and other artwork is on display. Other museums where Jain art is exhibited include the Prince of Wales Museum, Bombay, the museums at Bikaner, Udaipur, Jodhpur, Bharatpur, Ajmer and Jaipur, the Durgapur Art Gallery, the Jain Trust at Sirohi and many more in Rajasthan; museums in Hyderabad, Golconda and elsewhere in Andhra Pradesh; museums in Dhubela, Gwalior, Shirpuri, Raipur, Ujjain, Ratanpur, Deogarh, Lukknow, Khajuraho in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, Patna and Rajgir (Veerayatan) in Bihar; museums in Tamilnadu such as the Madras Government Museum and Pudukkotai museum; museums in Calcutta; and museums in Gujarat, such as the L.D. Institute of Indology, the Koba Aradhana dham and the Baroda museum. Museums Abroad: The Jain Centre, Leicester, has a purpose-built museum that depicts the history, philosophy, way of life and the contribution of Jainism to various fields.

The British Museum, London has early Jain sculptures belonging to the Gupta period (circa fifth century CE). The museum has exhibited sculptures of Risabhdeva, Mahavira, Parsvanatha and the guardian deities Sarasvati, Padmavati and Ambika. The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, has a beautiful bronze statue of Shantinatha, and stone and marble sculptures of Parsvanatha, Risabhdeva, Neminatha, Ambika and other art works. The Musée Guimet, Paris, has exhibited the head of a Jain image carved on the white-mottled red stone of the Mathura region, an eleventh century image of Risabhdeva, images of Parsvanatha, Mahavira, Bahubali, guardian deities of Mahavira, the wheel of the law and other Jain artefacts. Museum Für Indische Kunst, Berlin-Dahlem, contains a red sandstone head of a jina, stone sculptures of Mahavira and Rishabhdeva in meditation, and a bronze sculpture of a standing jina, surrounded by sitting jinas. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art has exhibited a bronze image of a tirthankara, a bronze image of three jinas, images of five jinas with Vimalanatha at its centre, and a bronze Shantinatha image with twenty-four jinas. The Nelson Gallery in Kansas City, the Seattle art museum and New York museum also contain sculptures and some examples of Jain artwork. A great exhibition of Jain art from India, presented at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1995-96 CE, brought the treasures of many museums and private collections to the attention of many thousands who visited it, or learned of it through the media.

Other fine arts, like dancing and music, vocal and instrumental, are still promoted by Jains, so far as these form part of religious devotion, worship and ritual. Jain literature, paintings and sculptures have numerous representations of, and references to, these arts. Several works on the art and science of music have been composed by Jains. Thus, the art of Jainism, has been developed over many centuries, even millennia, and is thriving in India and abroad. It is a true heritage of Jain thought and integral to the wider Indian heritage.

Dr. Natubhai Shah

Dr. Natubhai Shah