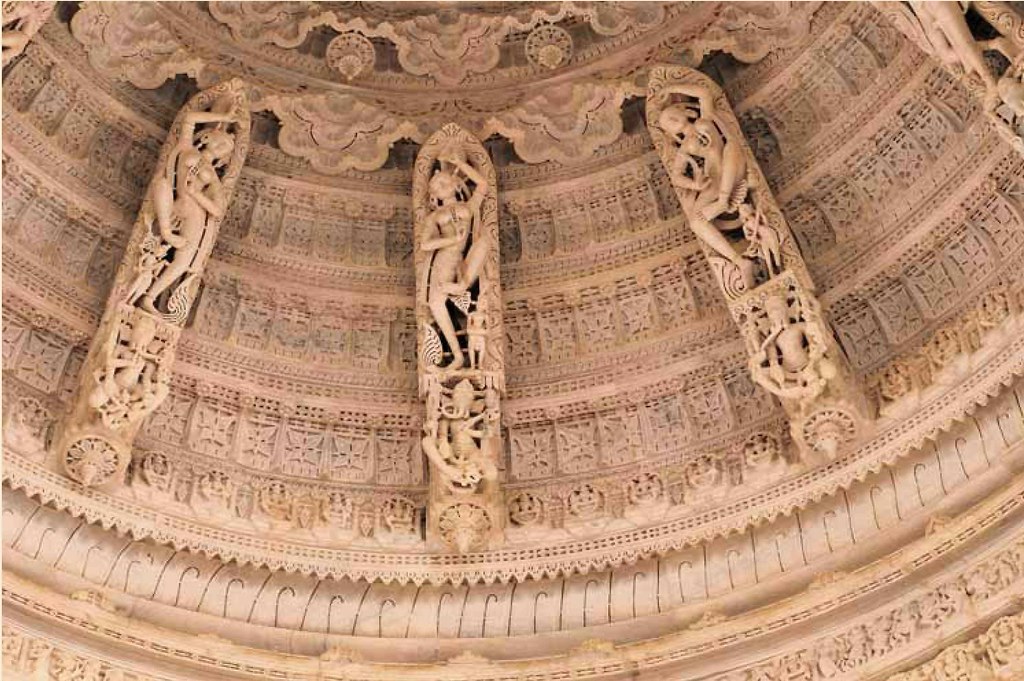

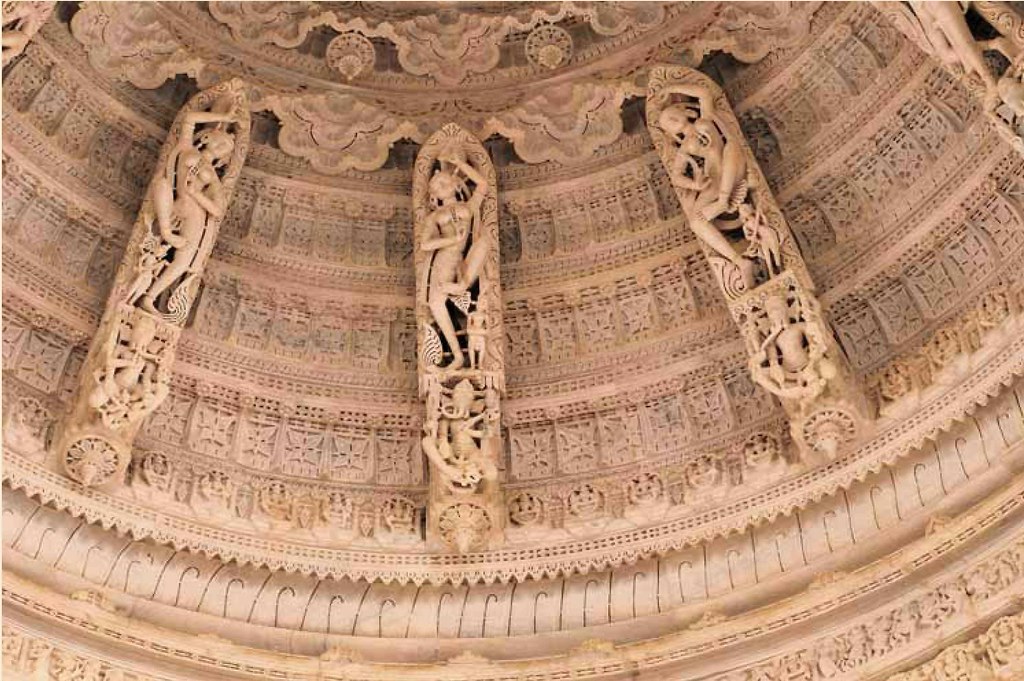

Female dancers in the dome of the southern meghanada-mandapaTogether with the extended shrines (no. 8 in the plan), the temple is surrounded by eighty-four devakulikas (no. 9 in the plan). It has the appearance of a classical vihara (temple based on the ground plan of a monastery), a common structure amongst the Jains. The figure eighty-four is representative of the twenty-four Tirthankaras of the past, present and future, respectively, plus the so-called twelve eternal Tirthankaras, of whom four each stand for one aeon respectively. The builder of this temple complex undoubtedly wanted to emulate the design on the first Adinatha temples as conceived and constructed, according to legend, by the sons of the first Tirthankara, Bharata and Bahubali. They too had eighty-four subsidiary shrines.

Female dancers in the dome of the southern meghanada-mandapaTogether with the extended shrines (no. 8 in the plan), the temple is surrounded by eighty-four devakulikas (no. 9 in the plan). It has the appearance of a classical vihara (temple based on the ground plan of a monastery), a common structure amongst the Jains. The figure eighty-four is representative of the twenty-four Tirthankaras of the past, present and future, respectively, plus the so-called twelve eternal Tirthankaras, of whom four each stand for one aeon respectively. The builder of this temple complex undoubtedly wanted to emulate the design on the first Adinatha temples as conceived and constructed, according to legend, by the sons of the first Tirthankara, Bharata and Bahubali. They too had eighty-four subsidiary shrines.

Despite the Islamic invasions of the 13th and 14th centuries, the Jains knew how to preserve the tradition of constructing their temples. In 1315, one Thakur Peru wrote a handbook on architecture, the vastu-sara. According to him, in front of the garbha griha, axially there should be three mandapas. Depaka adhered to even these guidelines.

These details can be deducted from the ground plan. I have deliberately gone into the minute details because these conceptions often tend to be lost in the labyrinth -like complexity of the interior. It should not however, be forgotten, that at the time of the inauguration in 1441, only the central sanctuary with the shrine and the four sabha mandapas were complete, as well as the adjoining western axis, i.e., the meghanada mandapa and the structure of the main portal. The structure as it exists today, is the result of a further century of continued construction. Innumerable donations have been made towards the project, even to the present day.

Female dancers in the dome of the southern meghanada-mandapa

Female dancers in the dome of the southern meghanada-mandapaIn comparison with the simplicity of the exterior, the interior is distinguished by a baroque-like ornateness. The individual sculptures may not always be of the highest quality; their movements frequently seem to be clumsy and jerky (see Plate 39), the arms and legs are not proportionate, appearing to thin out and the noses are too pointed. The sculptures clearly are not as important as the architecture; the function of the sculptures is the decoration and ornamentation of the edifice and not, as it is common in Europe, to highlight the value and beauty of sculpture per se. A feeling of horror vacui is evident, as relief seems to cover every inch. Apart from the purely ornamental and floral motifs, the Jains also used the entire repertory of Hindu iconography: deities, celestial musicians, danseuses, ganas (pot-bellied dwarfs), elephants and maithunas (lovers) as well as stories from the great epics of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. The eight dikpalas (guardians of the cardinal points), are placed on top of the pillars and the domes are typically adorned with the sixteen Jain goddesses of knowledge (vidya devis) and with celestial musicians and danseuses.